Leading New Technologies, Criss-Crossing Disciplines, Transcending Bias, and Leaving Us Resonating with Ourselves, Each Other, and the Cosmos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U2 to Perform at the 2009 MTV Europe Music Awards

U2 To Perform at the 2009 MTV Europe Music Awards HISTORIC PERFORMANCE AT BERLIN'S BRANDENBURG GATE LONDON, Oct 27, 2009 -- U2 will perform in front of Berlin's Brandenburg Gate on November 5, as part of the 16th MTV Europe Music Awards (EMAs), the news was announced today by MTV Networks International (MTVNI), owned by Viacom Inc. (NYSE: VIA, VIA.B). As a prelude to the Fall of The Wall celebrations in Berlin, U2 return to the city for a free ticketed performance which will be beamed into the 2009 MTV Europe Music Awards. U2's manager Paul McGuinness said: "It'll be an exciting spot to be in, 20 years almost to the day since the wall came down. Should be fun." Tickets to attend MTV EMAs present U2 at the Brandenburg Gate will be free of charge and available by registering on www.u2.com or www.mtvema.com from 9pm (CET) on Wednesday 28 October 2009. Tickets, which will take the form of a bar- coded e-ticket, will be available on a first-come, first-served basis and will be restricted to a maximum of 2 per applicant. Access to the performance will be strictly via one advance, scanned e-ticket per person. Tickets will not be available on the night of the show. Commented Antonio Campo Dall'Orto, EVP, Music Brands, MTV Networks International and Executive Producer for the MTV Europe Music Awards: "The exceptional musical heritage of this year's EMAs spans genres and generations and we are extremely proud to be bringing U2 to Berlin for this extraordinary performance. -

MTV Games, Harmonix and EA Announce Superstar Lineup for Rock Band(TM) Country Track Pack(TM)

MTV Games, Harmonix and EA Announce Superstar Lineup for Rock Band(TM) Country Track Pack(TM) Country's Biggest Artists Bring All New Tracks to The Rock Band Platform Including Willie Nelson, Trace Adkins, Miranda Lambert, Sara Evans and More CAMBRIDGE, Mass., June 15 -- Harmonix, the leading developer of music-based games, and MTV Games, a part of Viacom's MTV Networks, (NYSE: VIA, VIA.B), along with distribution partner Electronic Arts Inc. (Nasdaq: ERTS), today revealed the full setlist for Rock Band™ Country Track Pack™, which includes some of country's biggest artists from Willie Nelson, Alan Jackson and Montgomery Gentry to Kenny Chesney, Miranda Lambert, Sara Evans and more! Rock Band Country Track Pack hits store shelves in North America July 21, 2009 for a suggested retail price of $29.99 and will be available for Xbox 360® video game and entertainment system from Microsoft, PLAYSTATION®3 and PlayStation®2 computer entertainment systems, and Wii™ system from Nintendo. Rock Band Country Track Pack, featuring 21 tracks from country music's superstars of yesterday and today, is a standalone software product that allows owners of Rock Band® and Rock Band®2 to keep the party going with a whole new setlist. Thirteen of the on disc tracks are brand new to the Rock Band platform and will be exclusive to the Rock Band Country Track Pack disc for a limited time before joining the Rock Band® Music Store as downloadable content. In addition, Rock Band Country Track Pack, like all Rock Band software, is compatible with all Rock Band controllers, as well as most Guitar Hero® and authorized third party controllers and microphones. -

'Rock Vibe' Brings Electronic Music Game to Blind 23 February 2012, by Jennifer Pittman

'Rock Vibe' brings electronic music game to blind 23 February 2012, By Jennifer Pittman Bridging a divide between sighted and blind View, Calif., as a curriculum developer for summer gamers, University of California, Santa Cruz camps has been funding the project herself. She graduate Rupa Dhillon has created a version of the recently launched an online project fundraiser on musical rhythm "Rock Band" game that everyone Kickstarter.com to get enough cash to polish up a can play. second version of the game. In just a few weeks, she's raised about $12,500 in pledges from 29 "There aren't very many games that cross the backers, including a large financial endorsement divide between sighted users and people who are from Alex Rigopulos, chief executive officer of blind," said Dhillon, 27, who is sighted and known Harmonix Music Systems who has been a strong for her prowess playing Queen's "Bohemian supporter, according to Dhillon. Rhapsody." If she raises $16,500 by Feb. 25, she'll be able to "Rock Band," a popular game created several buy new tools and will donate some of the two- years ago by Boston-based Harmonix Music player games to organizations that work with blind Systems, visually cues players to press buttons on children. On Kickstarter, however, to minimize a "Rock Band" instrument, computer keyboard or funding risks, a project must reach its funding goal MIDI controller connected to their PC or Mac. by a specific deadline or no money changes hands. Players are scored according to how well they follow cues. The Kickstarter website accepts donations of $1 or more although higher donors get a few perks "Rock Vibe" translates the visual cues from "Rock such as the opportunity to request a favorite song Band" into tactile feedback so people who are blind be included in the game, including original works, or sighted can play. -

Before the Concert Begins, Please Turn on Your Cellphones

Comments Subscribe Members Starting at 99 cents Sign In Before the concert begins, please turn on your cellphones JOHNTLUMACKI/GLOBE STAFF NoteStream app developer Eran Egozy and research assistant Nathan Gutierrez. By Zoë Madonna GLOBE STAFF FEBRUARY 24, 2017 CAMBRIDGE — You may not know Eran Egozy’s name, but if you either were between the ages of 10 and 24 in the mid-2000s or had children in that ballpark, you may be familiar with one of the wildly successful video games on his resumé. Harmonix Music Systems, the video game development company he founded with fellow Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate Alex Rigopulos, brought the “Guitar Hero” and “Rock Band” franchises to living rooms and dorm lounges everywhere, introducing immersive, interactive technology through which non-musicians could play music. Now Egozy is turning his attention from the video game console to the concert hall with the app NoteStream. The app offers an alternative to the traditional program book, which delivers listeners a static wall of text that may be difficult to take in before the lights go down. NoteStream is designed to run on smartphones, displaying images and insights about a piece in real time as it is performed. “Our purpose is to engage with the audience more,” Egozy said at MIT, where he teaches. “We want people who are listening to music, especially if they’re listening for the first time, to be able to appreciate more of it as they’re listening to it.” NoteStream’s prototype outing was during an MIT Wind Ensemble performance of Percy Grainger’s English folk tune-inspired “A Lincolnshire Posy” in December. -

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE Mcgonigal

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE McGONIGAL THE PENGUIN PRESS New York 2011 ADVANCE PRAISE FOR Reality Is Broken “Forget everything you know, or think you know, about online gaming. Like a blast of fresh air, Reality Is Broken blows away the tired stereotypes and reminds us that the human instinct to play can be harnessed for the greater good. With a stirring blend of energy, wisdom, and idealism, Jane McGonigal shows us how to start saving the world one game at a time.” —Carl Honoré, author of In Praise of Slowness and Under Pressure “Reality Is Broken is the most eye-opening book I read this year. With awe-inspiring ex pertise, clarity of thought, and engrossing writing style, Jane McGonigal cleanly exploded every misconception I’ve ever had about games and gaming. If you thought that games are for kids, that games are squandered time, or that games are dangerously isolating, addictive, unproductive, and escapist, you are in for a giant surprise!” —Sonja Lyubomirsky, Ph.D., professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside, and author of The How of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Getting the Life You Want “Reality Is Broken will both stimulate your brain and stir your soul. Once you read this remarkable book, you’ll never look at games—or yourself—quite the same way.” —Daniel H. Pink, author of Drive and A Whole New Mind “The path to becoming happier, improving your business, and saving the world might be one and the same: understanding how the world’s best games work. -

Abstract the Goal of This Project Is Primarily to Establish a Collection of Video Games Developed by Companies Based Here In

Abstract The goal of this project is primarily to establish a collection of video games developed by companies based here in Massachusetts. In preparation for a proposal to the companies, information was collected from each company concerning how, when, where, and why they were founded. A proposal was then written and submitted to each company requesting copies of their games. With this special collection, both students and staff will be able to use them as tools for the IMGD program. 1 Introduction WPI has established relationships with Massachusetts game companies since the Interactive Media and Game Development (IMGD) program’s beginning in 2005. With the growing popularity of game development, and the ever increasing numbers of companies, it is difficult to establish and maintain solid relationships for each and every company. As part of this project, new relationships will be founded with a number of greater-Boston area companies in order to establish a repository of local video games. This project will not only bolster any previous relationships with companies, but establish new ones as well. With these donated materials, a special collection will be established at the WPI Library, and will include a number of retail video games. This collection should inspire more people to be interested in the IMGD program here at WPI. Knowing that there are many opportunities locally for graduates is an important part of deciding one’s major. I knew I wanted to do something with the library for this IQP, but I was not sure exactly what I wanted when I first went to establish a project. -

MTV Games, Harmonix and EA Ship Rock Band(TM) in the United Kingdom, France and Germany

MTV Games, Harmonix and EA Ship Rock Band(TM) in the United Kingdom, France and Germany Award-Winning Rock Band Will Be Available on Retail Shelves by End of Week GENEVA--(BUSINESS WIRE)--May 21, 2008--Rock Band begins its European invasion this week as Harmonix, the leading developer of music-based games, and MTV Games, a division of Viacom's MTV Networks (NYSE:VIA)(NYSE:VIA.B), along with marketing and distribution partner Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS), today announced that Rock Band has shipped to retail and will be available in the United Kingdom, France and Germany by the end of the week. Rock Band will have an exclusive launch window on the Xbox 360® video game and entertainment system from Microsoft beginning on May 23. Rock Band will be available for additional platforms later this summer. Rock Band is an all-new platform for music fans and gamers to interact with music. The game challenges players to put together a band and tour for fame and fortune, mastering lead/bass guitar, drums and vocals. With more master recordings than any other music game, Rock Band features some of the world's biggest rock artists and spans every genre of rock ranging from alternative and classic rock to heavy metal and punk. In addition to the 58 tracks from the North American release, Rock Band will feature nine new tracks spanning German, French and UK hits including: -- Blur "Beetlebum" (English)(1) -- Oasis "Rock 'n' Roll Star" (English) -- Tokio Hotel "Monsoon" (English) -- Muse "Hysteria" (English) -- Les Wampas "Manu Chao" (French) -- Playmo "New Wave" (French) -- Die Toten Hosen "Hier Kommt Alex" (German) -- Juli "Perfekte Welle" (German) -- H-Block X "Countdown to Insanity" (German) (1) indicates cover song In addition, Rock Band's unprecedented library of more than 110 songs available for purchase and download to date in North America is now available in Europe. -

Harmonix and MTV Games Make Major Music Announcements at Gamescom 2009

Harmonix and MTV Games Make Major Music Announcements at Gamescom 2009 Details for the Three Downloadable Albums Coming to "The Beatles™: Rock Band™" Music Store Revealed "All You Need Is Love" Available on 9/9/09 for $1.99 Tracks from Queen, Nirvana, Tom Petty, Elton John, Iggy Pop, The White Stripes, Pantera and More Coming Soon to the "Rock Band™" Platform Rock Band Catalog Surpasses 800 Songs Available to Date Scheduled to Hit 1000 Songs by Holiday 2009 COLOGNE, Germany, Aug. 19 -- Speaking at Gamescom 2009, Alex Rigopulos, CEO and cofounder of Harmonix, the world's leading developer of music-based games and a part of Viacom's MTV Networks (NYSE: VIA, VIA.B), today confirmed release details for the three Beatles albums that will be available for purchase as downloadable content in The Beatles™: Rock Band™ Music Store by the end of this year. Abbey Road will be released on October 20, 2009, followed by the release of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band in November and Rubber Soul in December. Additionally, Rigopulos revealed that tracks from Queen, Nirvana, Tom Petty, Elton John, Iggy Pop, The White Stripes, Pantera, Talking Heads, Korn, The Raconteurs and more will be among the artists coming to the various offerings across the Rock Band™ platform. With over 800 songs available to date via the Rock Band catalog and 1000 by end of 2009, the billion dollar selling and genre-defining Rock Band franchise continues to be the gold standard in music video games by completely dominating its closest competition with its massive music library, weekly downloadable content and artist offerings, innovation, and superior gameplay (Rock Band 2 average metacritic score: 92). -

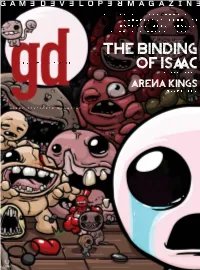

Game Developer Power 50 the Binding November 2012 of Isaac

THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE VOL19 NO 11 NOVEMBER 2012 INSIDE: GAME DEVELOPER POWER 50 THE BINDING NOVEMBER 2012 OF ISAAC www.unrealengine.com real Matinee extensively for Lost Planet 3. many inspirations from visionary directors Spark Unlimited Explores Sophos said these tools empower level de- such as Ridley Scott and John Carpenter. Lost Planet 3 with signers, artist, animators and sound design- Using UE3’s volumetric lighting capabilities ers to quickly prototype, iterate and polish of the engine, Spark was able to more effec- Unreal Engine 3 gameplay scenarios and cinematics. With tively create the moody atmosphere and light- multiple departments being comfortable with ing schemes to help create a sci-fi world that Capcom has enlisted Los Angeles developer Kismet and Matinee, engineers and design- shows as nicely as the reference it draws upon. Spark Unlimited to continue the adventures ers are no longer the bottleneck when it “Even though it takes place in the future, in the world of E.D.N. III. Lost Planet 3 is a comes to implementing assets, which fa- we defi nitely took a lot of inspiration from the prequel to the original game, offering fans of cilitates rapid development and leads to a Old West frontier,” said Sophos. “We also the franchise a very different experience in higher level of polish across the entire game. wanted a lived-in, retro-vibe, so high-tech the harsh, icy conditions of the unforgiving Sophos said the communication between hardware took a backseat to improvised planet. The game combines on-foot third-per- Spark and Epic has been great in its ongoing weapons and real-world fi rearms. -

Hibridando El Saber

Hibridando el saber. INVESTIGAR SOBRE COMUNICACIÓN Y MÚSICA. Miguel de Aguilera Ana Sedeño Eddy Borges Rey (Coordinadores) Hibridando el saber. Invesgar sobre comunicación y música. Miguel de Aguilera, Ana Sedeño, Eddy Borges Rey (Coordinadores) ISBN: 978-84-9747-325-5 Depósito legal: MA 1736-2010 Obra publicada en el Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad de Málaga (RIUMA) Disponible en la URI: http://hdl.handle.net/10630/4048 Comunicaciones presentadas para las I Jornadas de Invesgación Doctoral sobre Comunicación y Música, celebradas el 7 de junio de 2010 en el Aula Magna de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Comunicación de la Universidad de Málaga. Maquetación y diseño: Estefanía Marnez y Eddy Borges Rey Esta obra Esta obra está sujeta a una licencia Creative Commons: Reconocimiento - NoComercial - SinObraDerivada (cc-by-nc-nd): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/es/ Cualquier parte de esta obra se puede reproducir sin autorización pero con el reconocimiento y atribución a los autores. No se puede hacer uso comercial de la obra y no se puede alterar, transformar o hacer obras derivadas. Hibridando el saber. INVESTIGAR SOBRE COMUNICACIÓN Y MÚSICA. ÍNDICE 1. ENTRE EL PASADO Y EL FUTURO: LA INVESTIGACIÓN SOBRE COMUNICACIÓN Y MÚSICA EN MÁLAGA Miguel de Aguilera Ana Sedeño 9 2. EL PRECIO DE LA LIBERTAD REINVENTANDO LA ECONOMÍA ONLINE: CÓMO LOS CONTENIDOS “GRATUITOS” PUEDEN SER RENTABLES A LARGO PLAZO Gerd Leonhard 18 3. FILMOGRAFÍA MOZARTIANA PANORAMA HISTÓRICO POR LAS BANDAS SONORAS CON MÚSICA DE W. A. MOZART Alfonso Méndiz Noguero 24 4. APROXIMACIÓN A LA MEMÉTICA Y SUS POSIBLES APLICACIONES AL ESTUDIO DE LA MÚSICA EN EL CONTEXTO AUDIOVISUAL. -

Music Games Rock: Rhythm Gaming's Greatest Hits of All Time

“Cementing gaming’s role in music’s evolution, Steinberg has done pop culture a laudable service.” – Nick Catucci, Rolling Stone RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME By SCOTT STEINBERG Author of Get Rich Playing Games Feat. Martin Mathers and Nadia Oxford Foreword By ALEX RIGOPULOS Co-Creator, Guitar Hero and Rock Band Praise for Music Games Rock “Hits all the right notes—and some you don’t expect. A great account of the music game story so far!” – Mike Snider, Entertainment Reporter, USA Today “An exhaustive compendia. Chocked full of fascinating detail...” – Alex Pham, Technology Reporter, Los Angeles Times “It’ll make you want to celebrate by trashing a gaming unit the way Pete Townshend destroys a guitar.” –Jason Pettigrew, Editor-in-Chief, ALTERNATIVE PRESS “I’ve never seen such a well-collected reference... it serves an important role in letting readers consider all sides of the music and rhythm game debate.” –Masaya Matsuura, Creator, PaRappa the Rapper “A must read for the game-obsessed...” –Jermaine Hall, Editor-in-Chief, VIBE MUSIC GAMES ROCK RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME SCOTT STEINBERG DEDICATION MUSIC GAMES ROCK: RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME All Rights Reserved © 2011 by Scott Steinberg “Behind the Music: The Making of Sex ‘N Drugs ‘N Rock ‘N Roll” © 2009 Jon Hare No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Mktg5mktg5mktg

MKTG5MKTG5MKTG Chapter 1 Case Study: Harmonix Embrace Your Inner Rock Star Little more than three years ago, you had probably In 2000, Rigopulos and Egozy hit on a concept never heard of Harmonix. In 2005, the video game de- that would engage consumers, and Harmonix became sign studio released Guitar Hero, which subsequently a video game company. Where The Axe software pro- became the fastest video game in history to top $1 bil- vided an improvisation program with no set goal, most lion in North American sales. The game concept focuses video games were designed with a purpose and offered around a plastic guitar-shaped controller. Players press competition, which helped engage, direct, and motivate colored buttons along the guitar neck to match a se- players. At the time, the market for music-based games ries of dots that scroll down the TV in time with mu- had not fully developed, but especially in Japan, rhythm- sic from a famous rock tune, such as the Ramones’ “I based games, in which players would tap different com- Wanna Be Sedated” and Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the binations of buttons in time with a beat or a tune, were Water.” Players score points based on their accuracy. In becoming increasingly more popular. Harmonix created November 2007, Harmonix released Rock Band, adding two games, Frequency and Amplitude, in which play- drums, vocals, and bass guitar options to the game. Rock ers hit buttons along with a beat, unlocking tracks for Band has sold over 3.5 million units with a $169 price different layers of instruments in a song.