Refugee Return in Syria: Dangers, Security Risks and Information Scarcity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Second Quarterly Report on Besieged Areas in Syria May 2016

Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Colophon ISBN/EAN:9789492487018 NUR 698 PAX serial number: PAX/2016/06 About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan think tank based in Washington, DC. TSI was founded in 2015 in response to a recognition that today, almost six years into the Syrian conflict, information and understanding gaps continue to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the unfolding crisis. Our aim is to address these gaps by empowering decision-makers and advancing the public’s understanding of the situation in Syria by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Photo cover: Women and children spell out ‘SOS’ during a protest in Daraya on 9 March 2016, (Source: courtesy of Local Council of Daraya City) Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Table of Contents 4 PAX & TSI ! Siege Watch Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 8 Key Findings and Recommendations 9 1. Introduction 12 Project Outline 14 Challenges 15 General Developments 16 2. Besieged Community Overview 18 Damascus 18 Homs 30 Deir Ezzor 35 Idlib 38 Aleppo 38 3. Conclusions and Recommendations 40 Annex I – Community List & Population Data 46 Index of Maps & Tables Map 1. -

Syria and Repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP

30.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 330/21 DECISIONS COUNCIL DECISION 2012/739/CFSP of 29 November 2012 concerning restrictive measures against Syria and repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, internal repression or for the manufacture and maintenance of products which could be used for internal repression, to Syria by nationals of Member States or from the territories of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in Member States or using their flag vessels or aircraft, shall be particular Article 29 thereof, prohibited, whether originating or not in their territories. Whereas: The Union shall take the necessary measures in order to determine the relevant items to be covered by this paragraph. (1) On 1 December 2011, the Council adopted Decision 2011/782/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Syria ( 1 ). 3. It shall be prohibited to: (2) On the basis of a review of Decision 2011/782/CFSP, the (a) provide, directly or indirectly, technical assistance, brokering Council has concluded that the restrictive measures services or other services related to the items referred to in should be renewed until 1 March 2013. paragraphs 1 and 2 or related to the provision, manu facture, maintenance and use of such items, to any natural or legal person, entity or body in, or for use in, (3) Furthermore, it is necessary to update the list of persons Syria; and entities subject to restrictive measures as set out in Annex I to Decision 2011/782/CFSP. (b) provide, directly or indirectly, financing or financial assistance related to the items referred to in paragraphs 1 (4) For the sake of clarity, the measures imposed under and 2, including in particular grants, loans and export credit Decision 2011/273/CFSP should be integrated into a insurance, as well as insurance and reinsurance, for any sale, single legal instrument. -

WFP SYRIA External SITREP 16-30 November 2014

WFP SYRIA CRISIS RESPONSE Situation Update 12-25 NOVEMBER 2014 SYRIA LEBANON JORDAN TURKEY IRAQ EGYPT “All it takes is US$1 from 64 million people.” WFP launches 72-hour social media campaign to raise urgently needed funds DOLLAR wfp.org/forsyrianrefugees for Syrian for Refugees HIGHLIGHTS - Funding shortfalls force WFP to cut assistance to Syrian refugees in December - Inter-agency convoy delivers food for 5,000 people in Syria’s west Harasta for the first time in almost two years - WFP delivers food supplies across lines of conflict to 35,000 civilians in rural Aleppo, northern Syria - Inter-agency targeting tool finalized in Lebanon - Pilot areas for non-camp voucher assistance identified in Turkey - Voucher distributions to begin in Iraq's Darashakran and Arbat camps in December Eight year-old Bija and six year-old Ali from Damascus,Syria, Al Za’atri camp, Jordan. WFP/Joelle Eid For information on WFP’s Syria Crisis Response, please use the QR Code or access through the link: wfp.org/syriainfo FUNDING AND SHORTFALLS Funding shortages force WFP to halt food assistance in December Despite significant advocacy efforts and the generous support from our donors, insufficient funding is finally forcing WFP to cut its assistance to millions of Syrian refugees throughout the region in December, when winter hits the region. As a result, we are suspending our response in Lebanon - only new arrivals will receive food parcels; cutting our programme in Jordan by 85 percent by only assisting camp refugees and suspending our support to urban refugees; and cutting our programmes in Turkey and Egypt by providing vouchers of a much lower value than their regular entitlements. -

FSS Wos Response Analysis

SO1 RESPONSE MARCH 2017 CYCLE Y PEOPLE IN NEED N I 8 B G Food & Livelihood 7.0 7.0 7.0 I 9 7 6.3 6.3 6.3 5.38million Assistance HED OR Food Basket Million C e 6 l Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) - 2017 6.16 D SO1 5.8 5.89 5.78 5 N 4 M m 1.16.338m M 5.38 3.35 Target REA September 2015 8.7 Million 5.15 A From within Syria From neighbouring e 4 countries June 2016 9.4 Million WHOLE OF SYRIA ES ES Million peop I nc September 2016 9.0 Million 129,657 3 Cash and Voucher ITI LIFE SUSTAINING AND LIFE SAVING AR ta OVERALL TARGET MARCH 2017 RESPONSE 2 BENEFICIARIES Reached s FOOD ASSISTANCE (SO1) TARGET SO1 Food Basket, Cash & Voucher i Beneficiaries 1 Food Basket, ICI Cash & Voucher - ODAL Additionally, Bread - Flour and Ready to Eat Rations were also Provided ss 7 EF 5.38 0 life sustaining Million M 9 Million OCT NOV DEC JAN FEB MAR N a E nsecure Million Emergency i d B 2 Response (77%) of SO1 Target o 608,654 1.84 M Million Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) - 2017 2.45million From within Syria From neighbouring od 36°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 42°0'0"E Bread-Flour fo countries 7 7 o c 1 Cizre- f 1 0 g! i 0 ng 2 Nusaybin-Al i 2 Kiziltepe-Ad l T U R K E Y Qamishli Peshkabour T U R K E Y Darbasiyah n Ayn al g! ! g! h g Arab Ceylanpinar-Ras c b Al Ayn Al Yaroubiya 170,555 r Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus g! - Rabiaa tai Akcakale-Tall ! Emergency Response with 116,265 a g! g! g g! 54,290 u Bab As Abiad Ready to Eat Ration From neighbouring M Salama Cobanbey g! From within Syria - countries ssessed g! g! p sus ) a 1 t e Reyhanli - A L --H A S A K E H fe -

Access Resource

The State of Justice Syria 2020 The State of Justice Syria 2020 Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) March 2020 About the Syria Justice and Accountability Centre The Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) strives to prevent impunity, promote redress, and facilitate principled reform. SJAC works to ensure that human rights violations in Syria are comprehensively documented and preserved for use in transitional justice and peace-building. SJAC collects documentation of violations from all available sources, stores it in a secure database, catalogues it according to human rights standards, and analyzes it using legal expertise and big data methodologies. SJAC also supports documenters inside Syria, providing them with resources and technical guidance, and coordinates with other actors working toward similar aims: a Syria defined by justice, respect for human rights, and rule of law. Learn more at SyriaAccountability.org The State of Justice in Syria, 2020 March 2020, Washington, D.C. Material from this publication may be reproduced for teach- ing or other non-commercial purposes, with appropriate attribution. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for commercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Cover Photo — A family flees from ongoing violence in Idlib, Northwest Syria. (C) Lens Young Dimashqi TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 2 Introduction 4 Major Violations 7 Targeting of Hospitals and Schools 8 Detainees and Missing Persons 8 Violations in Reconciled Areas 9 Property Rights -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

Export Agreement Coding (PDF)

Peace Agreement Access Tool PA-X www.peaceagreements.org Country/entity Syria Region Middle East and North Africa Agreement name Damascus Truce I between Bayt Sahem and Babila Date 17/02/2014 Agreement status Multiparty signed/agreed Interim arrangement No Agreement/conflict level Intrastate/local conflict ( Syrian Conflicts (1948 - ) (1976 - 2005) (2011 - ) ) Stage Ceasefire/related (Ceasefire) Conflict nature Government Peace process 133: Intra-Syrian Process (state/non-state) Parties Leaders of Bayt Sahem and Babila (Syrian Opposition); Syrian Government; Third parties Description Short ceasefire negotiated between the Syrian Government and the leaders of Bayt Sahem and Babila in the Damascus Countryside. Provides guarantees of Syrian Army to not enter the towns, re-supply water and electricity, open roads, and allow fighters that wish to surrender to do so, in addition to surrendering heavy weaponry. Agreement document SY_140115_Truce Agreement in Bayt Sahem and Babila_EN.pdf [] Agreement document SY_140115_Truce Agreement in Bayt Sahem and Babila_AR.pdf [] (original language) Local agreement properties Process type Informal but persistent process Explain rationale -> no support mechanism, link to the national peace process, culture of signing No formal mechanism supported the signing of the agreement, which was negotiated by public figures. It is part of a choreography of local agreements signed at that time in the countryside of Aleppo. Indeed, in addition to Babbila and Beit Sahem, similar deals have been struck for Qudsaya, Moadamiyet al-Sham, Barzeh, Yalda and Yarmuk Palestinian refugee camp Is there a documented link Yes to a national peace process? Link to national process: The agreement seems to be linked to the national peace process. -

Syrian Arab Republic

Syrian Arab Republic News Focus: Syria https://news.un.org/en/focus/syria Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria (OSES) https://specialenvoysyria.unmissions.org/ Syrian Civil Society Voices: A Critical Part of the Political Process (In: Politically Speaking, 29 June 2021): https://bit.ly/3dYGqko Syria: a 10-year crisis in 10 figures (OCHA, 12 March 2021): https://www.unocha.org/story/syria-10-year-crisis-10-figures Secretary-General announces appointments to Independent Senior Advisory Panel on Syria Humanitarian Deconfliction System (SG/SM/20548, 21 January 2021): https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20548.doc.htm Secretary-General establishes board to investigate events in North-West Syria since signing of Russian Federation-Turkey Memorandum on Idlib (SG/SM/19685, 1 August 2019): https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sgsm19685.doc.htm Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels V Conference, 29-30 March 2021 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2021/03/29-30/ Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels IV Conference, 30 June 2020: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2020/06/30/ Third Brussels conference “Supporting the future of Syria and the region”, 12-14 March 2019: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2019/03/12-14/ Second Brussels Conference "Supporting the future of Syria and the region", 24-25 April 2018: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2018/04/24-25/ -

EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International Is a Global Movement of More Than 7 Million People Who Campaign for a World Where Human Rights Are Enjoyed by All

‘LEFT TO DIE UNDER SIEGE’ WAR CRIMES AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: MDE 24/2079/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Residents search through rubble for survivors in Douma, Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus. Activists said the damage was the result of an air strike by forces loyal to President Bashar -

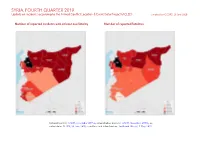

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief – March 2018 Page 1

Aid in Danger Aid agencies Monthly News Brief March 2018 Insecurity affecting the delivery of aid Security Incidents and Access Constraints This monthly digest comprises threats and incidents of Africa violence affecting the delivery Central African Republic of aid. It is prepared by 05 March 2018: In Paoua town, Ouham-Pendé prefecture, and across Insecurity Insight from the wider Central African Republic, fighting among armed groups information available in open continues to stall humanitarian response efforts. Source: Devex sources. 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, rumours of All decisions made, on the basis an armed attack in the city forced several unspecified NGOs to of, or with consideration to, withdraw. Source: RJDH such information remains the responsibility of their 07 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, protesters at respective organisations. a women’s march against violence in the region called for the departure of MINUSCA and the Moroccan UN contingent from Editorial team: Bangassou, accusing them of passivity in the face of threats and Christina Wille, Larissa Fast and harassment. Source: RJDH Laurence Gerhardt Insecurity Insight 09 or 11 March 2018: In Bangassou city, Mbomou prefecture, armed men suspected to be from the Anti-balaka movement invaded the Andrew Eckert base of the Dutch NGO Cordaid, looting pharmaceuticals, work tools, European Interagency Security motorcycles and seats. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Forum (EISF) Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) personnel intervened, leading to a firefight between MINUSCA and the armed Research team: men. The perpetrators subsequently vandalised the local Médecins James Naudi Sans Frontières (MSF) office. Cars, motorbikes and solar panels Insecurity Insight belonging to several NGOs in the area were also stolen.