The-Story-Behind-The-Xmas-Kings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walks Programme: July to September 2021

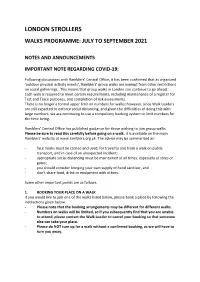

LONDON STROLLERS WALKS PROGRAMME: JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2021 NOTES AND ANNOUNCEMENTS IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING COVID-19: Following discussions with Ramblers’ Central Office, it has been confirmed that as organized ‘outdoor physical activity events’, Ramblers’ group walks are exempt from other restrictions on social gatherings. This means that group walks in London can continue to go ahead. Each walk is required to meet certain requirements, including maintenance of a register for Test and Trace purposes, and completion of risk assessments. There is no longer a formal upper limit on numbers for walks; however, since Walk Leaders are still expected to enforce social distancing, and given the difficulties of doing this with large numbers, we are continuing to use a compulsory booking system to limit numbers for the time being. Ramblers’ Central Office has published guidance for those wishing to join group walks. Please be sure to read this carefully before going on a walk. It is available on the main Ramblers’ website at www.ramblers.org.uk. The advice may be summarised as: - face masks must be carried and used, for travel to and from a walk on public transport, and in case of an unexpected incident; - appropriate social distancing must be maintained at all times, especially at stiles or gates; - you should consider bringing your own supply of hand sanitiser, and - don’t share food, drink or equipment with others. Some other important points are as follows: 1. BOOKING YOUR PLACE ON A WALK If you would like to join one of the walks listed below, please book a place by following the instructions given below. -

Neighbourhood Policing Evaluation

Agenda Item 9 Neighbourhood Policing Evaluation London Area Baselining Study September 2009 British Transport Police 1 Contents_______________________________________ __________ Executive summary 2 Background 4 Methodology 6 Case Studies 1 Croydon 11 2 Wimbledon 19 3 Finsbury Park 27 4 Seven Sisters 35 5 Acton Mainline 41 6 Stratford 48 Officer survey findings 55 Appendix 58 Quality of Service Research Team Strategic Development Department Strategic Services Force Headquarters 25 Camden Road London, NW1 9LN Tel: 020 7830 8911 Email: [email protected] British Transport Police 2 Executive summary______________________________________ Many of the rail staff who took part in the evaluation spoke of feeling neglected by a police service that they perceived to be more engaged with its own organisational agenda than with the needs of its users. This was evidenced by the failure of BTP’s current policing arrangements to reflect the needs of staff effectively. Of great interest was the way in which many staff spoke of their hopes and expectations for the future. The introduction of NP was often described in glowing terms, considered capable of providing the visible, accessible and familiar police presence that staff thought was needed to close the gap that had developed between themselves and BTP. Indeed, the strongest message for NPTs is that staff confidence may appear low, but their expectations are high. It became clear throughout the evaluation that each site has its own narrative – its own unique collection of challenges, customs and conflicts which can only be understood by talking to those with ‘local’ knowledge. Indeed, as will become clear throughout the following report, the experiential knowledge of those who work on and regularly use the railways is at present a largely untapped resource. -

153 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

153 bus time schedule & line map 153 Finsbury Park Station View In Website Mode The 153 bus line (Finsbury Park Station) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Finsbury Park Station: 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM (2) Liverpool Street: 4:48 AM - 11:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 153 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 153 bus arriving. Direction: Finsbury Park Station 153 bus Time Schedule 33 stops Finsbury Park Station Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM Monday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM Liverpool Street Station (C) Sun Street Passage, London Tuesday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM Moorgate Station (B) Wednesday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM 142-171 Moorgate, London Thursday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM Finsbury Street (S) Friday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM 72 Chiswell Street, London Saturday 12:10 AM - 11:50 PM Silk Street (BM) 47 Chiswell Street, London Barbican Station (BA) Aldersgate Street, London 153 bus Info Direction: Finsbury Park Station Clerkenwell Road / Old Street (BQ) Stops: 33 60 Goswell Road, London Trip Duration: 45 min Line Summary: Liverpool Street Station (C), Clerkenwell Road / St John Street Moorgate Station (B), Finsbury Street (S), Silk Street 64 Clerkenwell Road, London (BM), Barbican Station (BA), Clerkenwell Road / Old Street (BQ), Clerkenwell Road / St John Street, Aylesbury Street Aylesbury Street, Percival Street (UJ), Spencer Street 159-173 St John Street, London / City University (UK), Rosebery Avenue / Sadler's Wells Theatre (UL), St John Street / Goswell Road Percival Street (UJ) (P), Chapel Market (V), Penton Street / Islington St. -

Finsbury Park

FINSBURY PARK Park Management Plan 2020 (minor amendments January 2021) Finsbury Park: Park Management Plan amended Jan 2021 Section Heading Page Contents Foreword by Councillor Hearn 4 Draft open space vision in Haringey 5 Purpose of the management plan 6 1.0 Setting the Scene 1.1 Haringey in a nutshell 7 1.2 The demographics of Haringey 7 1.3 Deprivation 8 1.4 Open space provision in Haringey 8 2.0 About Finsbury Park 2.1 Site location and description 9 2.2 Facilities 9 2.3 Buildings 17 2.4 Trees 18 3.0 A welcoming place 3.1 Visiting Finsbury Park 21 3.2 Entrances 23 3.3 Access for all 24 3.4 Signage 25 3.5 Toilet facilities and refreshments 26 3.6 Events 26 4.0 A clean and well-maintained park 4.1 Operational and management responsibility for parks 30 4.2 Current maintenance by Parks Operations 31 4.3 Asset management and project management 32 4.4 Scheduled maintenance 34 4.5 Setting and measuring service standards 38 4.6 Monitoring the condition of equipment and physical assets 39 4.7 Tree maintenance programme 40 4.8 Graffiti 40 4.9 Maintenance of buildings, equipment and landscape 40 4.10 Hygiene 40 5.0 Healthy, safe and secure place to visit 5.1 Smoking 42 5.2 Alcohol 42 5.3 Walking 42 5.4 Health and safety 43 5.5 Reporting issues with the ‘Love Clean Streets’ app 44 5.6 Community safety and policing 45 5.7 Extending Neighbourhood Watch into parks 45 5.8 Designing out crime 46 5.9 24 hour access 48 5.10 Dogs and dog control orders 49 6.0 Sustainability 6.1 Greenest borough strategy 51 6.2 Pesticide use 51 6.3 Sustainable use of -

Board Date: 3 February 2016 Item: Commissioner's Report This Paper Will Be Considered in Public 1 Summary 2 Recommendation

Board Date: 3 February 2016 Item: Commissioner’s Report This paper will be considered in public 1 Summary 1.1 This report provides an overview of major issues and developments since the meeting of the Board held on 17 December 2015 and updates the Board on significant projects and initiatives. 2 Recommendation 2.1 That the Board note the report. List of appendices to this report: Commissioner’s Report – February 2016 List of Background Papers: None Mike Brown MVO Commissioner Transport for London February 2016 Commissioner’s Report 03 February 2016 This paper will be considered in public 1 Introduction This report provides a review of major issues and developments since the meeting of the Board held on 17 December 2015 and updates the Board on significant projects and initiatives. Cover image: ZeEus London trial launch at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park 2 Commissioner’s Report 2 Delivery A full update on operational performance the successful conclusion of talks with the will be provided at the next Board meeting Trades Unions. We continue to work with on 17 March in line with the quarterly the Trades Unions to avoid unnecessary strike Operational and Financial Performance action, and reach an agreement on rosters and Investment Programme Reports. and working practices. Mayor’s 30 per cent Lost Customer LU has taken the decision to implement its Hours target – London Underground long term solution for Train Drivers, recruiting Following significant improvements in the part-time drivers specifically for the Night reliability of London Underground’s train Tube. These vacancies were advertised services, the Mayor set a target in 2011 internally and externally before Christmas, with aiming to further reduce delays on London more than 6,000 applications received, which Underground (LU) by 30 per cent by the end are now being processed. -

View of the Three Barbican Centre Towers from the Shard's Viewing

View of the three Barbican Centre towers from the Shard’s viewing platform. Islington is in the background including the Emirates Stadium. 80 6 LOCAL SEARCH 6.1 INTRODUCTION 6.2 LOCAL SEARCH This chapter covers the ‘Local Search’ for Any future proposal for a tall building on one METHODOLOGY opportunities for tall buildings within the areas of the identified sites will need to comply with identified by the ‘Strategic Search’ in Section 5. the relevant policy criteria which will be set The following methodology is applied for each out in the Council’s Local Plan and/or in a site search area: Strategic Search Areas have a potential to include specific planning guidance. sites that might be appropriate for tall buildings. 01 URBAN DESIGN ANALYSIS The Local Search looks at identifying local It further will also be subject to additional opportunities for tall buildings within these search technical impact assessments, design scrutiny This establishes an understanding of the local areas. through design review and engagement with character of the area, and includes the following: the planning authority and the local community. The methodology for the Local Search is based This will test and scrutinise impacts, which • Identification of character areas; on the Historic England Tall Buildings Advice fall beyond the scope of this Tall Buildings Note, which recommends the undertaking of • Assessment of existing building heights study, such as impacts on nearby residents characterisation and building heights studies to help including any taller buildings; -

Finsbury Park Station Step-Free Access UNITED KINGDOM

Finsbury Park Station Step-Free Access UNITED KINGDOM PROJECT OF THE YEAR INCLUDING RENOVATION (UP TO €50M) MICHAEL NARDONE, PG VICE PRESIDENT AMERICAS 18TH NOVEMBER 2019 Miami, USA 18th November 2019 Authored by Ben Ablett Finsbury Park Station Step-Free Access – United Kingdom Project Summary Challenges Solutions, Sustainability & Safety Achievements Miami, USA 18th November 2019 Finsbury Park Station Step-Free Access – United Kingdom A $25M project with multiple challenges and complexities • Project constructed safely while maintaining all station operations • Holistic Integrated approach temporary and permanent works and construction methodology • Design Innovation solutions utilising Hand Mining techniques • Maintaining and adapting existing assets • Controlling ground movement using discrete excavations and support systems. Miami, USA 18th November 2019 PROJECT SUMMARY Finsbury Park Station Step-Free Access – United Kingdom Bus Station (Wells Terrace) Lift Shaft 1 Worksite Lift Shaft 3 Bus Station Worksite (Station Place) Miami, USA 18th November 2019 PROJECT SUMMARY Finsbury Park Station Step-Free Access – United Kingdom Lift Shaft 2 (Unrealised) Lift Shaft 3 Works Lift Shaft 1 Works Miami, USA 18th November 2019 PROJECT SUMMARY Finsbury Park Station Step-Free Access – United Kingdom Passageway 4 Works Lift Shaft 3 Works Lift Shaft 1 Works • Two new lift shafts and stair structures Underground • Passageway extension Platform Tunnels • New openings into existing passages • Demolition of existing stairs Miami, USA 18th November 2019 -

Sub-Regional Transport Plan 2010

1 CONTENTS Mayoral foreword 3 London Councils foreword 3 Executive summary 4 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: Supporting economic development and 28 population growth Chapter 3: Enhancing the quality of life for all Londoners 61 Chapter 4: Improving the safety and security of all 80 Londoners Chapter 5: Improving transport opportunities for all 86 Londoners Chapter 6: Reducing transport‟s contribution to climate 94 change & improving its resilience Chapter 7: Supporting delivery of London 2012 Olympic 99 and Paralympic Games and its legacy Chapter 8: Key places in north sub-region 100 Chapter 9: Delivery of the Plan and sustainability 109 assessment Chapter 10: Next steps 112 Appendices Appendix 1: Implementation Plan 114 Appendix 2: List of figures 124 2 MAYORAL FOREWORD LONDON COUNCILS FOREWORD Following my election in 2008, I set out my desire for TfL to “listen and learn Boroughs play a key role in delivering the transport that London needs and deserves. from the boroughs... help them achieve their objectives and... negotiate However, there are many transport issues that cross borough boundaries and this is where solutions that will benefit the whole of London”. I therefore asked TfL to embark the Sub-regional Transport Plans (SRTPs) are particularly important. The SRTPs fill the gap between the strategic policies and proposals in the Mayor‟s Transport Strategy (MTS) and on a new collaborative way of working with the boroughs, based on sub-regions. the local initiatives in boroughs‟ Local Implementation Plans (LIPs). As well as better collaboration, the sub-regional programme has led to an We have very much welcomed the Greater London Authority and TfL‟s willingness to improved analytical capability, which has enabled travel patterns to be better engage with London Councils and the boroughs on the development of the SRTPs over the understood and provided for. -

Fairbridge Road, N19 £950,000 Share of Freehold

Fairbridge Road, N19 £950,000 Share of Freehold Fairbridge Road, N19 A beautiful three/four-bedroom, split-level conversion, occupying the upper floors of a period home with rear balcony and garden. Located on a popular turning on Upper Holloway, providing excellent access to local shops and amenities, including Archway and Finsbury park stations with Waterlow Park and range of desired local schools in close proximity. Further comprising one/two receptions, kitchen, two bathrooms and ample eaves storage. Benefitting from a host of desired character features, including cornicing, sash windows and fireplaces. Offered with no onward chain. Lease: 125 years from 1987 Building Insurance: 75% Ground Rent: NA EPC Rating: C Current: 70 Potential: 80 £950,000 Share of Freehold 020 8348 5515 [email protected] An Overview of Archway The London Borough of Islington was formed in 1965 by merging the former metropolitan boroughs of Islington and Finsbury. Attractions include: Almeida Theatre, Business Design Centre, Emirates Stadium, House of Detention museum, Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, Islington Local History Centre, Islington Museum, The King's Head Theatre and London Canal Museum. Street markets to visit include Camden Passage, Chapel Market, Exmouth Market, Nag's Head Market and Whitecross Street Market. Parks and open spaces: Barnard Park, Bingfield Park, Bunhill Fields, Caledonian Park, Gillespie Park, Highbury Fields, Paradise Park, Rosemary Gardens, Spa Fields Gardens and Whittington Park. Transport - Islington has a wide variety of transportation services, with direct connections to the suburbs and the City and West End. Islington also has 10 tube stations within its boundaries, with connections by the tube to all around London. -

Business Plan 2013

Business Plan 2013 Transport for London’s plans into the next decade. Business Plan 2013 Transport for London’s plans into the next decade. Contents Message from the Mayor 4 Our people: Dedicated to customer service 60 Commissioner’s foreword 6 An organisation fit for London 62 Introduction 9 Continually improving 63 Supporting jobs across the UK 65 Customers: The heart of our business 10 Getting the basics right 12 Value: Getting more for less 68 An accessible system 16 The 2013 Spending Review 70 Improving the customer experience Our funding 74 through technology 21 Sustainable use of our resources 78 Engaging with our stakeholders 24 Managing risks 79 Partnership working and funding improvements 27 Financial tables 80 Delivery: Our plans and our promises 28 Our capability 28 A foundation of well-maintained infrastructure 30 Maximising capacity on our network 34 Unlocking growth for the future of London 42 Making life in London better 49 Our delivery timeline 58 Transport for London – Business Plan 2013 3 London is a world leader in business, culture and Message from the Mayor education, and its success is, in part, fuelled by the investments we make. As the Capital’s population and economy service from 2015 are all on the way. Crossrail, investment and improvements is absolutely continue to grow, there has never been more the Northern line extension, and improved essential. My next challenge is to persuade pressure on London’s transport network. bus, Overground, Docklands Light Railway the Government to help provide the funds to Yet thanks to our neo-Victorian surge of (DLR) and tram services are no longer a pipe support it. -

153 Liverpool Street - Islington - Finsbury Park Daily „

153.qxd 17/10/03 9:46 am Page 1 153 Liverpool Street - Islington - Finsbury Park Daily „ Angel Nag's Head John Street stbourne Road Liverpool StreetMoorgateBarbican StationBarbican Arts„ Ê CentreClerkenwell StationSt „ ÊRoadIslingtonLiverpool Copenhagen Road Hemingford Street RoadWe MackenzieHolloway Road Finsbury Park •••• Station „ Ê • ••••• Richmond • Avenue• • • Station „ Ê Monday - Friday Liverpool Street Station „ Ê 0500 0520 0540 0600 0615 0630 1852 1905 1920 1935 1950 2010 2030 2050 2110 2130 Moorgate Station „ Ê 0505 0525 0545 0605 0620 0636 1900 1913 1927 1942 1957 2017 2037 2057 2117 2137 Barbican Station „ Ê 0509 0529 0549 0609 0624 0640 Then about 1904 1917 1932 1946 2001 2021 2041 2101 2121 2141 Clerkenwell Road St John Street 0511 0531 0551 0611 0626 0642 every 1907 1920 1934 1949 2003 2023 2043 2103 2123 2143 Islington Angel „ 0516 0536 0556 0616 0632 0649 12 minutes 1916 1928 1942 1956 2010 2029 2049 2109 2129 2149 Barnsbury Hemingford Arms 0519 0539 0559 0619 0635 0652 until 1921 1933 1947 2000 2014 2033 2053 2113 2133 2153 Holloway Nag’s Head 0525 0545 0605 0625 0642 0700 1933 1944 1957 2010 2023 2041 2101 2121 2141 2201 Finsbury Park Station „ Ê 0529 0549 0609 0629 0647 0705 1941 1952 2004 2017 2029 2047 2107 2127 2147 2207 Liverpool Street Station „ Ê 2150 10 30 50 0010 Moorgate Station „ Ê 2157 Then every 17 37 57 0017 Barbican Station „ Ê 2201 20 minutes,214101 0021 Clerkenwell Road St John Street 2203 at these 23 43 03 until 0023 Islington Angel „ 2209 minutes 29 49 09 0029 Barnsbury Hemingford Arms 2213 past the -

Please Reply

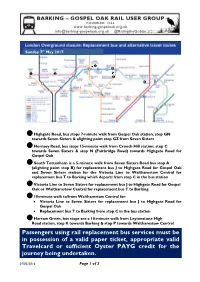

Sunday 7th May 2017 Highgate Road, bus stops 7-minute walk from Gospel Oak station; stop GN towards Seven Sisters & alighting point stop GZ from Seven Sisters Hornsey Road, bus stops 15-minute walk from Crouch Hill station; stop C towards Seven Sisters & stop N (Fairbridge Road) towards Highgate Road for Gospel Oak South Tottenham is a 5-minute walk from Seven Sisters Road bus stop A (alighting point stop B) for replacement bus J to Highgate Road for Gospel Oak and Seven Sisters station for the Victoria Line to Walthamstow Central for replacement bus T to Barking which departs from stop C in the bus station Victoria Line to Seven Sisters for replacement bus J to Highgate Road for Gospel Oak or Walthamstow Central for replacement bus T to Barking 10-minute walk to/from Walthamstow Central for: Victoria Line to Seven Sisters for replacement bus J to Highgate Road for Gospel Oak Replacement bus T to Barking from stop C in the bus station Harrow Green, bus stops are a 10-minute walk from Leytonstone High Road station, stop K towards Barking & stop P towards Walthamstow Central Passengers using rail replacement bus services must be in possession of a valid paper ticket, appropriate valid Travelcard or sufficient Oyster PAYG credit for the journey being undertaken. 07/05/2016 Page 1 of 2 SUNDAY 7TH MAY 2017 RAIL REPLACEMENT BUS ROUTE ‘T’ BARKING – WALTHAMSTOW CENTRAL Barking Station, bus stop K, outside the station for departing buses; Bus stop H for arrivals East Ham station, bus stop B westbound (to pick up only); Bus stop