Conference Report AMA Conference 2003 Conference Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undergraduate Prospectus 2020/21 WORKS IT HOW STUDY BA BEYOND SCHOOLS LABS US ABOUT CONTENTS

SCHOOL OF ARTS + MEDIA SCHOOL OF DESIGN + COMMUNICA- 1 TION SCHOOL OF CRITICAL + CULTURAL STUDIES MAKING AN APPLICATION A bursary that you won’t have to pay back: Your accommodation guaranteed: If you’re a home (UK) student, you’ll be As a first year student you are guaranteed eligible to receive financial support from Halls of Residence accommodation within the us throughout your studies to help cover city, close to our campus. We work with Host programme and travel costs. As it’s a and Clever Student Lets to ensure you can bursary, you won’t have to pay it back choose suitable accommodation close to our and you’ll still have access to other funds campus that suits your budget. and bursaries if you need them. For more information please see our website. OPEN DAYS AND INTERVIEWS Our Open Days are a chance for you and your to attend in January and February, but we friends or family to visit Plymouth, meet and can see you whenever you feel ready. For chat with our friendly programme leaders advice on what we are looking for in terms of and admissions staff, tour our studios and motivation and creative potential, see p4 in facilities, visit student accommodation and our How It Works guide. discuss the best study options for you. Worried about travel costs or already attended Book your place at plymouthart.ac.uk/opendays an Open Day? We can also set up an online and we’ll send travel offers, recommendations or telephone interview. You’ll always be for hotels, and details of workshops and alumni interviewed by a subject expert who will speakers in advance. -

Conference Market Demand Study Plymouth 2020

Bridget Baker Consulting CONFERENCE MARKET DEMAND STUDY PLYMOUTH JUNE 2020 1 Bridget Baker Consulting Ltd Plymouth City Council – Conference Demand Study Bridget Baker Consulting Ltd 30 Southdown Avenue Brighton BN1 6EG Phone +44(0) 1273 560655 Mobile +44 (0)7941 461 180 [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Executive Summary 4 3. Supply & Pricing of Conference and Events Facilities in and around Plymouth 8 4. Conference & Events Demand in Plymouth 11 5. Regionally Competitive Destination in the UK now and in the Future 24 6. Overview of the Demand Trends in the Conference & Events Market in the UK & South West of England 27 Appendices A – Plymouth Organisations contacted & Conference Plymouth members B – Events Bookers Interviewed in Telephone Research C – Local Conference Venue Survey D - Recent/Booked Large Events at Venues in the South West www.bridgebaker.co.uk 2 Plymouth City Council – Conference Demand Study 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Background Plymouth City Council (PCC) are keen to understand the current situation regarding the conference and events market in Plymouth. The study is also be used to identify opportunities and strategies to support ‘MICE’ activity and subsequent economic growth in the city. A summary of the key aims are: • An overview of the current volume and value of ‘MICE’ (Meetings, Incentive, Conference and Events) activity within the city; • Identification of gaps in provision within the city and its immediate environment; • An overview of the current national and international ‘MICE’ sector; • Identification of key market opportunities both short and longer term. This report responds to your brief. -

Outdoor Queueing, Knicker Throwing and 100Th Birthday Greetings : Newspaper Narratives of Mature Female Fans. DELLER, Ruth A

Outdoor queueing, knicker throwing and 100th birthday greetings : newspaper narratives of mature female fans. DELLER, Ruth A. <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4935-980X> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/12943/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version DELLER, Ruth A. (2016). Outdoor queueing, knicker throwing and 100th birthday greetings : newspaper narratives of mature female fans. In: BENNETT, Lucy and BOOTH, Paul, (eds.) Seeing Fans : Representations of Fandom in Media and Popular Culture. Bloomsbury Academic, 197-207. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Outdoor queuing, knicker-throwing and 100th birthday greetings: newspaper narratives of mature female fans Ruth A Deller, Sheffield Hallam University In this chapter, I explore the way mature (50+1) female fans are presented in a range of local and national English-speaking newspapers from around the world. I focus here specifically on female fans of male solo singers, particularly to explore the way gendered fandom is presented when the women are older than the teenage female fans most often associated with male artists (Ehrenreich et al 1992; Din and Cullingford 2004). Hodkinson notes that participation in music subcultures has often been 'regarded as a temporary accompaniment to the broader experience of being adolescent' (2011: 262) and Cavicchi argues that: The obsessive activities of fandom - collecting artifacts and photographs, imitating a star's dress and manners, camping overnight for concert tickets, creating fanzines, joining fan clubs - are accepted only as the temporary behaviour of hormone-driven (usually female) teenagers, who, when reaching adulthood, are expected to settle into the more mature behavior of work or motherhood (1998: 6) Yet, it is becoming clear that music fandom is no longer the sole preserve of the young. -

A Global Industry

CHAPTER •••• 1 A global industry Introduction The conference industry is a young, dynamic industry which is growing and maturing at a rapid rate. From origins in Europe and North America, it is now a truly international industry witnessing huge investments across all continents. Its youthfulness, however, does mean that it lacks some of the necessary characteristics of more established industries, such as well defined terminology, adequate market intelligence, appropriate education and training structures and clear entry routes. Conferences are part of the business tourism (or business events) sector, a major though often under-valued sector of the wider tourism industry. This chapter looks at: • the origins of the conference industry • the foundations of a proper industry • the industry’s recent globalisation • world rankings of leading cities and countries • certain industry shortcomings • industry parameters and definitions • business tourism and leisure tourism • the benefits of conference and business tourism. It includes case studies on: • City of Melbourne, Australia • The Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, London, England • Hyderabad International Convention Centre, India • Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates • Coral Beach Hotel and Resort, Paphos, Cyprus. Conferences and Conventions Learning outcomes On completion of this chapter, you should be able to: • Explain why and how the conference industry developed in the way it did • Understand the international dimensions of the industry and appreciate which are the most successful cities -

Michael Mcintyre's Big World Tour Dates

MICHAEL MCINTYRE’S BIG WORLD TOUR 2018 UK & IRELAND TOUR DATES ANNOUNCED **Presale tickets available from 10am, Wednesday 3rd May 2017** **General sale tickets available from: 10am, Friday 5th May 2017** “The man is quite simply top-to-toe hilarious” 5 Stars - Daily Telegraph Britain’s biggest comedian Michael McIntyre is set to return to the stage with his eagerly awaited new tour and this time he is going global! Michael McIntyre’s Big World Tour will see Michael perform to arenas across the UK and Ireland in 2018 as well as revisiting Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, South Africa and Norway and heading to America, Canada, Switzerland, Iceland, Sweden, Malta and the Netherlands for the first time. Tickets for Michael’s UK and Ireland tour dates go on general sale from 10am on Friday 5th May, with pre-sale tickets available from 10am on Wednesday 3rd May. Tickets will be available to purchase from www.michaelmcintyre.co.uk Please find a full list of dates and listings information below - more dates will be announced shortly. In the UK, Michael has sold over 1.5 million tickets, including a record-breaking 28 performances at London’s 16,000 capacity 02 Arena where he was awarded the keys to venue in 2015, alongside musical talents Prince, Take That and One Direction. Around the world, Michael has previously sold out arenas in New Zealand, Australia and Dubai and he holds the record for the biggest selling comedy shows in South Africa and Norway. 2016 saw the launch of Michael’s own television show Michael McIntyre’s Big Show on BBC One. -

Terms of Reference and Conduct of the Inquiry

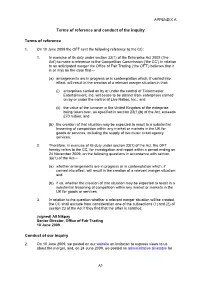

APPENDIX A Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry Terms of reference 1. On 10 June 2009 the OFT sent the following reference to the CC: 1. In exercise of its duty under section 33(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 (‘the Act’) to make a reference to the Competition Commission (‘the CC’) in relation to an anticipated merger the Office of Fair Trading (‘the OFT’) believes that it is or may be the case that— (a) arrangements are in progress or in contemplation which, if carried into effect, will result in the creation of a relevant merger situation in that: (i) enterprises carried on by or under the control of Ticketmaster Entertainment, Inc. will cease to be distinct from enterprises carried on by or under the control of Live Nation, Inc.; and (ii) the value of the turnover in the United Kingdom of the enterprise being taken over, as specified in section 23(1)(b) of the Act, exceeds £70 million; and (b) the creation of that situation may be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition within any market or markets in the UK for goods or services, including the supply of live music ticket agency services. 2. Therefore, in exercise of its duty under section 33(1) of the Act, the OFT hereby refers to the CC, for investigation and report within a period ending on 24 November 2009, on the following questions in accordance with section 36(1) of the Act— (a) whether arrangements are in progress or in contemplation which, if carried into effect, will result in the creation of a relevant merger situation; and (b) if so, whether the creation of that situation may be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition within any market or markets in the UK for goods or services. -

Micky Flanagan - Back in the Game Pdf

FREE MICKY FLANAGAN - BACK IN THE GAME PDF Micky Flanagan | none | 10 Apr 2014 | Redbush Entertainment Ltd | 9781909613140 | English | Watford, United Kingdom The Back in the Game Tour - Wikipedia Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? Check out our picks for family friendly movies movies that transcend all ages. Micky Flanagan - Back in the Game even more, visit our Family Entertainment Guide. See the full list. Recorded live at London's Hackney Empire, join one of the nation's best-loved comedians performing to his home crowd in this hilarious brand new DVD packed full of guaranteed laughter. After seeing him live I brought the DVD and have since watched it 3 or 4 times, with each viewing being as enjoyable as the previous. Back In Micky Flanagan - Back in the Game Game is even better than his first stand up, It has a very similar feel and thankfully he didn't change his style and approach, he is still the crafty cockney with a light-hearted and unique look at the world. Micky Flanagan is easily one of my favourite stand-up comedians and Back in the Game is a personal favourite of mine. It is a shame that we only have two DVDs to enjoy; hopefully he continues to tour the country Micky Flanagan - Back in the Game many more years as it would be a disaster for him not to! Looking for something to watch? Choose an adventure below and discover your next favorite movie or TV show. Visit our What to Watch page. Sign In. -

Comp Comm Report 2010 (TM and LN) – Appendices and Glossary

APPENDIX A Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry Terms of reference 1. On 10 June 2009 the OFT sent the following reference to the CC: 1. In exercise of its duty under section 33(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 (‘the Act’) to make a reference to the Competition Commission (‘the CC’) in relation to an anticipated merger the Office of Fair Trading (‘the OFT’) believes that it is or may be the case that— (a) arrangements are in progress or in contemplation which, if carried into effect, will result in the creation of a relevant merger situation in that: (i) enterprises carried on by or under the control of Ticketmaster Entertainment, Inc. will cease to be distinct from enterprises carried on by or under the control of Live Nation, Inc.; and (ii) the value of the turnover in the United Kingdom of the enterprise being taken over, as specified in section 23(1)(b) of the Act, exceeds £70 million; and (b) the creation of that situation may be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition within any market or markets in the UK for goods or services, including the supply of live music ticket agency services. 2. Therefore, in exercise of its duty under section 33(1) of the Act, the OFT hereby refers to the CC, for investigation and report within a period ending on 24 November 2009, on the following questions in accordance with section 36(1) of the Act— (a) whether arrangements are in progress or in contemplation which, if carried into effect, will result in the creation of a relevant merger situation; and (b) if so, whether the creation of that situation may be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition within any market or markets in the UK for goods or services. -

London Southend Airport... Hello Europe

Monday, March 26, 2012 The world’s most popular free newspaper Damon’s back with yet another project Just don’t call it a supergroup, even if that’s exactly what it»p33-34 is Cowell ‘face to face with armed raider’ A WOMAN will appear in court by TARIQ TAHIR detained by Cowell’s security today after Simon Cowell came staff. Nothing was thought to have face-to-face with an armed intruder ‘over-zealous fan’. One friend been stolen from the property. at his £7.5million mansion. added: ‘It was a frightening expe- Leanne Zaloumis, from Catford, An arrest was made on Saturday rience. Simon’s fine but shaken up south London, has been charged night after reports of a disturbance – because he didn’t expect some- with aggravated burglary – defined at the pop mogul’s house in west thing like that to happen.’ under the Theft Act as a break-in London. The incident happened shortly involving a gun, imitation gun, Officers who arrived at the prop- after the first episode of Cowell’s offensive weapon or explosives. erty – the former French ambass- new series of Britain’s Got Talent Cowell who is estimated to be ador’s residence in Holland Park was aired on ITV. worth as much as £300million, – found a woman had forced her The intruder was said to have splits his time between homes in way into the premises. got in through a downstairs win- London and Los Angeles. Sources close to Mr Cowell, 52, dow, after evading extensive secu- Shaken up: Simon Cowell said the intruder was probably an rity at the property. -

Michael Mcintyre's Big World Tour

MICHAEL MCINTYRE’S BIG WORLD TOUR 2018 UK & IRELAND TOUR DATES **EXTRA UK DATES ANNOUNCED** ** New dates on sale from Friday 22nd September at 10am ** “The man is quite simply top-to-toe hilarious” 5 Stars - Daily Telegraph Due to phenomenal public demand, Britain’s biggest comedian Michael McIntyre has added an extra 8 dates to his eagerly anticipated 2018 UK tour - Michael McIntyre’s Big World Tour. New dates have been added in Plymouth, Nottingham, Cardiff, Newcastle, Birmingham, Brighton as well as two extra nights at London’s O2 Arena. Find a full list of dates and listings information below. Tickets for these extra dates are on sale from Friday 22nd September at 10am, except for Nottingham Motorpoint Arena (25th March), which is on sale now. Tickets for all of Michael’s UK and Ireland tour dates are available to purchase from www.michaelmcintyre.co.uk. Michael McIntyre’s Big World Tour will see the BAFTA award-winning comedian perform to arenas across the UK and Ireland in 2018 as well as revisiting Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, South Africa and Norway and heading to America, Canada, Switzerland, Iceland, Sweden, Malta and the Netherlands for the first time. In the UK, Michael has sold over 1.5 million tickets, including a record-breaking 28 performances at London’s 16,000 capacity O2 Arena where he was awarded the keys to venue in 2015, alongside musical talents Prince, Take That and One Direction. Around the world, Michael has previously sold out arenas in New Zealand, Australia and Dubai and he holds the record for the biggest selling comedy shows in South Africa and Norway. -

Www .Maver Ic K

JANUARY/FeBRUARY 2014 www.maverick-country.com MAVERICK FROM THE EDITOR... MEET THE TEAM Editor t is with a great deal of sadness, that I acknowlege that this will be my last issue as Alan Cackett editor of Maverick. I have always believed that when you no longer enjoy doing 24 Bray Gardens, Loose, Maidstone, Kent, ME15 9TR, UK something, then it’s time to stop and look to do something di erent. I have had a 01622 744481 Igood run as editor, and now is the time to hand over to someone younger. Someone who [email protected] can hopefully take the magazine forward, embracing country music’s future whilst not Managing Editor overlooking its huge legacy of the past. I know that the new editor Laura Bethell who Michelle Teeman 01622 823920 worked with me for 5 years, 2 as my deputy editor, will do just that. [email protected] It was just over 47 years ago that I edited and published Britain’s rst regular monthly country music magazine. Looking back that was quite an audacious and bold undertaking Designer Laura Bethell for a teenager from a council house estate who le school at 15. Some of the original 01622 823922 readers of Country Music Monthly are still around and have continued to follow my writing [email protected] and views on the music as readers of Maverick. ere was a time when I not only knew Editorial Assistant many of the Maverick readers’ names but had a personal contact with them, but recently Chris Beck I’ve lost touch and I have to say that I miss the chats that we used to have when they phoned Project Manager up to renew their subscriptions. -

New Entertainment Venue (Exeter): Needs Assessment

New Entertainment Venue (Exeter): Needs Assessment New Entertainment Venue Advisory Group (NEVAG) 18 September 2017 New Entertainment Venue (Exeter): Needs Assessment Contents Executive Summary Report 1 Introduction 9 1.1 New Entertainment Venue Advisory Group 9 1.2 Study Brief & Process 9 2 Where is the demand / supply gap? 11 2.1 Strategic context 11 2.2 Exeter’s arts and culture ‘ecology’ 11 2.3 Review of venues 12 2.4 Review market demand 14 2.5 Review of arts programming 16 3 What are the key venue considerations? 19 3.1 Balance between bespoke and proven models 19 3.2 Venue flexibility & acoustic 19 3.3 Get-in / get-out and turning the venue around 20 3.4 Venue revenues 21 4 Where should it be located? 23 4.1 Unanimous support for City Centre 23 4.2 Regeneration Opportunity 23 4.3 City Centre sites 24 4.4 Review of city centre sites 24 5 How could it be developed and sustained? 27 5.1 A ‘centre for arts’ 27 5.2 Funding 28 5.3 Commercial property market 30 5.4 Meanwhile use / interim measures 31 Appendices 1 List of Consultees 34 2 Strategic Context Review 35 3 Market Demand Analysis 43 3.1 Resident Market 43 3.2 Tourist Market 59 2 New Entertainment Venue (Exeter): Needs Assessment 4 Market Supply Analysis 61 4.1 Arts Council England: National Portfolio 2018-22 61 4.2 Venues in the South West (c.90-minute drive-time) 61 4.3 Proposed Venue Expansions and Renovations 64 5 UK Theatres & Operators 69 5.1 UK Theatre / Arts Centres (+1,000 seats) 69 5.2 National (UK) Theatre Operators 70 5.3 Broadcasting Theatres 72 6 Venue Case Studies 75 7 Exeter Sites’ Assessments 92 3 New Entertainment Venue (Exeter): Needs Assessment Executive Summary Summarised below are the key findings from this study with references included to the more detailed analysis and evidence laid out in the Report and Appendices.