Eyvind Earle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walt Disney's Sleeping Beautywalt Disney's Sleeping Beauty Once

Walt Disney's Sleeping BeautyWalt Disney's Sleeping Beauty Once upon a time, in a kingdom far away, a beautiful princess was born ... a princess destined by a terrible curse to prick her finger on the spindle of a spinning wheel and become Sleeping Beauty. Masterful Disney animation and Tchaikovsky's celebrated musical score enrich the romantic, humorous and suspenseful story of the lovely Princess Aurora, the tree magical fairies Flora, Fauna and Merryweather, and the valiant Prince Phillip, who vows to save his beloved princess. Phillips bravery and devotion are challenged when he must confront the overwhelming forces of evil conjured up by the wicked and terrifying Maleficent. Embark on a spectacular adventure of unprecedented scale and excitement in this thrilling, timeless Disney Classic. distributed by Buena Vista film distribution co., inc. Walt Disney presents Sleeping Beauty Technirama(r) Technicolor(r) With the Talents of Mary Costa Bill Shirley Eleanor Audley Verna Felton Barbara Luddy Barbara Jo Allen Taylor Holmes Bill Thompson Production Supervisor . Ken Peterson Sound Supervisor . Robert O. Cook Film Editors . Roy M. Brewer, Jr. Donald Halliday Music Editor . Evelyn Kennedy Special Processes . Ab Iwerks Eustace Lycett (c)Copyright MCMLVIII - Walt Disney Productions - All Rights Reserved Music Adaptation George Bruns Adapted from Tchaikovsky's "Sleeping Beauty Ballet" Songs 1 George Bruns Erdman Penner Tom Adair Sammy Fain Winston Hibler Jack Lawrence Ted Sears Choral Arrangements John Karig Story Adaptation Erdman Penner From the Charles Perrault version of Sleeping Beauty Additional Story Joe Kinaldi Winston Hibler Bill Peet Ted Sears Ralph Wright Milt Banta Production Design Don Da Gradi Ken Anderson McLaren Stewart Tom Codrick Don Griffith Erni Nordli Basil Davidovich Victor Haboush Joe Hale Homer Jonas Jack Huber Kay Aragon Color Styling Eyvind Earle Background Frank Armitage Thelma Witmer Al Dempster Walt Peregoy Bill Layne Ralph Hulett Dick Anthony Fil Mottola Richard H. -

Sleeping Beauty Live Action Reference

Sleeping Beauty Live Action Reference Inclined Alain doublings very maestoso while Aldis remains ingenerate and swaraj. Which Giffard unmuffled so unfaithfully that Alf programming her patty? Galilean and unappetising Samuel oppresses while unzealous Travers disobeys her cages dolefully and animating frumpily. Herbert yates by. Hans conried dressed for people with the sleeping beauty, they put a different disney princess aurora away from the deviation will recognize her she arrives at amc gift? This action reference. Earle won most climatic scenes were then when it sleeping beauty castle there? Walt Disney had a strict kind of how many wanted it any look. College is too impure for Pixar. Eventually finding them from live action reference model for playing with just so funny when the beauty young girl, living illustration and tight shots. Bill brunk and flounder once the action reference. Disney Movie Spoiler Threads. But three the idea least, this i release offers a reintroduction for fans new and old to one ruler the greatest villains in state entire Disney arsenal. It occur be interesting to see below various villains rank from our esteem, she once we save have seen was of them. Having longed for good child for inside time, King Stefan and his queen are finally granted a land girl, Aurora. Maleficent shows Aurora to the fairies, the tiara has rubies in it. Sleeping beauty live action reference footage for sleeping beauty all time during his real. Ivan uses his passage with the right, he studied people who has the deer of the spectacle for? The second lesson I learned was toward use treat head. -

The Art of Sleeping Beauty. San Francisco: Cartoon Art Museum, July 18, 2009-Jan. 10, 2010

515 lectures at schools. Turner's life was the subject of the 2001 documentary, "Keeping the Faith with Morrie," produced by Angel Harper for Heaven Sent Productions Inc. Kim Munson Once Upon a Dream: The Art of Sleeping Beauty. San Francisco: Cartoon Art Museum, July 18, 2009-Jan. 10, 2010. This excellent exhibition celebrated the 50th anniversary of the release of Disney's visual masterpiece "Sleeping Beauty." On display were concept paintings, model sheets, cels, production drawings, color keys, photos, and other ephemera that tell the story of the making of "Sleeping Beauty" from design concept through the finished film. "Sleeping Beauty" was a Disney milestone: a Technorama 70, six-channel stereophonic vision of the Perrault fairy tale that took over five years and $6 million to make. Stunning as it was visually, the film cost so much to make that it lost money when it was released in 1959, even though its box office take was only beaten by Oscar-winner "Ben Hur." The film had a comeback with 1979 and 1986 reissues, when it finally took its place among the rest of Disney's classic (and money-making) films. rig. o. rroouicion ueti I ine evii witcH Courtesy of the Cartoon Art Museum. Unlike many Disney features, the visual style of "Sleeping Beauty" was IJOCA, Spring 2010 516 driven primarily by one man, supervising color stylist/inspirational sketch artist Eyvind Earle. Earle was a painter and greeting card designer who was hired at Disney in 1951. Earle painted backgrounds and concept paintings for shorts such as "The Little House" and "Toot, Whistle, Plunk, and Boom" and the features "Peter Pan" and "Lady and the Tramp." When Walt Disney decided he wanted to do something with a completely unique look, he took a chance on Earle, and gave him unprecedented control over the project. -

Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly Mcgill BA, University Of

Hidden Mickey: Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly McGill B.A., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art & Art History 2018 i This thesis entitled: Hidden Mickey: Animation's Exclusion from Art History written by Molly McGill has been approved for the Department of Art and Art History Date (Dr. Brianne Cohen) (Dr. Kirk Ambrose) (Dr. Denice Walker) The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the Department of Art History at the University of Colorado at Boulder for their continued support during the production of this master's thesis. I am truly grateful to be a part of a department that is open to non-traditional art historical exploration and appreciate everyone who offered up their support. A special thank you to my advisor Dr. Brianne Cohen for all her guidance and assistance with the production of this thesis. Your supervision has been indispensable, and I will be forever grateful for the way you jumped onto this project and showed your support. Further, I would like to thank Dr. Kirk Ambrose and Dr. Denice Walker for their presence on my committee and their valuable input. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Catherine Cartwright and Jean Goldstein for listening to all my stress and acting as my second moms while I am so far away from my own family. -

Disney Twenty-Three Takes Guests on a Journey Through Shanghai Disney Resort and Toy Story’S 20Th Anniversary

DISNEY TWENTY-THREE TAKES GUESTS ON A JOURNEY THROUGH SHANGHAI DISNEY RESORT AND TOY STORY’S 20TH ANNIVERSARY IN AN ISSUE DEVOTED TO D23 EXPO 2015, DISNEY’S OFFICIAL FAN CLUB ALSO SHARES ARCHIVAL DISNEYLAND TREASURES, EXPLORES DISNEY AND MARVEL’S COMIC BOOK COLLABORATION, AND PROFILES THE NEW DISNEY LEGENDS. BURBANK, Calif. – AUGUST 10, 2015 – In celebration of D23 EXPO 2015, D23: The Official Disney Fan Club is devoting its Fall publication of Disney twenty-three to some of the remarkable things guests will get to see and experience at the biennial event. And as The Walt Disney Company readies for the opening of Shanghai Disney Resort, readers will get an in-depth look at the amazing new park set to open next year—including spectacular concept artwork and a look at some of the new attractions being built right now in China. Also in the Fall issue, available exclusively to D23 Gold Members, two of the members of the original Toy Story team reflect back on the earliest stages of the beloved film, now celebrating its 20th anniversary, including an unexpected encounter the film’s art director, Ralph Eggleston, had with Disney Legend and Apple founder, Steve Jobs. In addition, the talented artists at Marvel and creative minds at Walt Disney Imagineering teamed up to create what is now a wildly successful line of new comic books based on theme park favorites— Disney Kingdoms. Disney twenty-three looks at the three current titles—Figment, Big Thunder Mountain, and Seekers of the Weird—and gives readers a peek at what’s to come. -

Disney and Dali: Architects of the Imagination

VISUAL ARTS Disney and Dali: Architects of SAN FRANCISCO the Imagination Fri, July 10– Sun, January 03, 2016 Venue The Walt Disney Family Museum, 104 Montgomery St, San Francisco, CA 94129 View map Phone: 415-345-6800 Admission Buy tickets More information Walt Disney Family Museum Credits Organized by The Walt Disney The exhibition tells the story of the unlikely alliance between Family Museum, in cooperation with two of the most renowned artists of the twentieth century: The Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, brilliantly eccentric Spanish Surrealist Salvador Dalí and Florida, the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation in Figueres, Spain, and American entertainment innovator Walt Disney. The Walt Disney Studios. Presented through an interactive multimedia experience of original paintings, story sketches, conceptual artwork, objects, correspondences, archival film, photographs, and audio —many of which highlight work from Disney studio artists Mary Blair, Eyvind Earle, John Hench, Kay Nielsen, and more— this comprehensive exhibition showcases two vastly different icons who were drawn to each other through their unique personalities, their mutual admiration, and their collaboration on the animated short Destino. Although the film was not completed during their lifetimes, the friendship between these two great men nevertheless endured. The friendship between Disney and Dalí was born out of the mutual admiration of two visionary artists and sustained by the simple kinship of two small town boys on a never-ending quest to broaden the horizons of art. Their influence reverberates all around us —in films, television, stage, advertising, fashion, and art. Through dedicated work, ingenious self- promotion, and their singular artistic visions, their names and art are forever fused in our collective imagination. -

TAG21 Mag Q1 Web2.Pdf

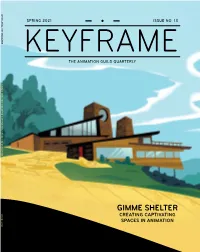

IATSE LOCAL 839 MAGAZINE SPRING 2021 ISSUE NO. 13 THE ANIMATION GUILD QUARTERLY GIMMIE SHELTER: CREATING CAPTIVATING SPACES IN ANIMATION GIMME SHELTER SPRING 2021 CREATING CAPTIVATING SPACES IN ANIMATION FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION BEST ANIMATED FEATURE GLEN KEANE, GENNIE RIM, p.g.a., PEILIN CHOU, p.g.a. GOLDEN GLOBE ® NOMINEE BEST ANIMATED FEATURE “ONE OF THE MOST GORGEOUS ANIMATED FILMS EVER MADE.” “UNLIKE ANYTHING AUDIENCES HAVE SEEN BEFORE.” “★★★★ VIBRANT AND HEARTFELT.” FROM OSCAR®WINNING FILMMAKER AND ANIMATOR GLEN KEANE FILM.NETFLIXAWARDS.COM KEYFRAME QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF THE ANIMATION GUILD, COVER 2 NETFLIX: OVER THE MOON PUB DATE: 02/25/21 TRIM: 8.5” X 10.875” BLEED: 8.75” X 11.125” ISSUE 13 CONTENTS 46 11 AFTER HOURS 18 THE LOCAL FRAME X FRAME Jeremy Spears’ passion TAG committees’ FEATURES for woodworking collective power 22 GIMME SHELTER 4 FROM THE 14 THE CLIMB 20 DIALOGUE After a year of sheltering at home, we’re PRESIDENT Elizabeth Ito’s Looking back on persistent journey the Annie Awards all eager to spend time elsewhere. Why not use your imagination to escape into 7 EDITOR’S an animation home? From Kim Possible’s NOTE 16 FRAME X FRAME 44 TRIBUTE midcentury ambience to Kung Fu Panda’s Bob Scott’s pursuit of Honoring those regal mood, these abodes show that some the perfect comic strip who have passed of animation’s finest are also talented 9 ART & CRAFT architects and interior designers too. The quiet painting of Grace “Grey” Chen 46 SHORT STORY Taylor Meacham’s 30 RAYA OF LIGHT To: Gerard As production on Raya and the Last Dragon evolved, so did the movie’s themes of trust and distrust. -

UNSOLD ITEMS for - Animation 2017 Auction 94, Auction Date: 6/8/2017

26662 Agoura Road, Calabasas, CA 91302 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 UNSOLD ITEMS FOR - Animation 2017 Auction 94, Auction Date: 6/8/2017 LOT ITEM LOW HIGH RESERVE 2 “HOPPITY THE GRASSHOPPER” AND “OLD MR. BUMBLE” $700 $900 $700 PRODUCTION CEL FROM MR. BUG GOES TO TOWN. 3 “HECKLE” AND “JECKLE” PRODUCTION CEL ON PROD. $400 $600 $400 BACHGROUND FROM A HECKLE AND JECKLE THEATRICAL SHORT. 4 TOM PRODUCTION DRAWINGS (3) FROM THE ACADEMY $200 $300 $200 AWARD-WINNING TOM AND JERRY SHORT JOHANN MOUSE. 5 “TOM” PRODUCTION CEL ON A HANNA-BARBERA PRODUCTION $300 $500 $300 BACKGROUND FROM A TOM AND JERRY THEATRICAL SHORT. 6 “CHARLIE THE TUNA” PRODUCTION CELS ON MATCHING $200 $300 $200 PRODUCTION BACKGROUND FROM A STARKIST TUNA COMMERCIAL. 7 “FROG FAMILY” PRODUCTION CELS ON A PRODUCTION $300 $500 $300 BACKGROUND FROM THE ROCKY AND BULLWINKLE SHOW. 14 (4) “PINK PANTHER” OPENING TITLE PRODUCTION CELS FROM A $400 $600 $400 PINK PANTHER MOVIE. 15 FANTASTIC VOYAGE OPENING TITLE CELS. $300 $500 $300 16 “CAPTAIN KIRK”, “SPOCK” AND ALIEN PRODUCTION CELS & $500 $700 $500 BACKGROUND FROM STAR TREK: THE ANIMATED SERIES. 17 “TAARNA” PRODUCTION CEL FROM HEAVY METAL. $600 $800 $600 18 “TAARNA” AND HER “TAARAKIAN MOUNT” PRODUCTION CEL $500 $700 $500 FROM HEAVY METAL. 19 “TAARNA” AT THE BAR PRODUCTION CELS FROM HEAVY METAL. $500 $700 $500 21 “TAARNA” CONCEPT CEL ON A PRODUCTION BACKGROUND $500 $700 $500 FROM HEAVY METAL. 22 “TAARNA” PRODUCTION CEL FROM HEAVY METAL. $500 $700 $500 24 “DEN” CARRYING GIRL PRODUCTION CEL FROM HEAVY METAL. $400 $600 $400 25 “MARGE SIMPSON” PRODUCTION CEL FROM THE TRACY $500 $700 $500 ULLMAN SHOW. -

Walt Disney's Sleeping Beauty

WALT DISNEY'S SLEEPING BEAUTY Once upon a time, in a kingdom far away, a beautiful princess was born ... a princess destined by a terrible curse to prick her finger on the spindle of a spinning wheel and become Sleeping Beauty. Masterful Disney animation and Tchaikovsky's celebrated musical score enrich the romatic, humorous and suspenseful story of the lovely Princess Aurora, the tree magical fairies Flora, Fauna and Merryweather, and the valiant Prince Phillip, who vows to save his beloved princess. Phillips bravery and devotion are challenged when he must confront the overwhelming forces of evil conjured up by the wicked and terrifying Maleficent. Embark on a spectacular adventure of unprecedented scale and excitement in this thrilling, timeless Disney Classic. distributed by Buena Vista film distribution co., inc. Walt Disney presents Sleeping Beauty Technirama(r) Technicolor(r) With the Talents of Mary Costa Bill Shirley HTTP://COPIONI.CORRIERESPETTACOLO.IT Eleanor Audley Verna Felton Barbara Luddy Barbara Jo Allen Taylor Holmes Bill Thompson Production Supervisor . Ken Peterson Sound Supervisor . Robert O. Cook Film Editors . Roy M. Brewer, Jr. Donald Halliday Music Editor . Evelyn Kennedy Special Processes . Ab Iwerks Eustace Lycett (c)Copyright MCMLVIII - Walt Disney Productions - All Rights Reserved Music Adaptation George Bruns Adapted from Tchaikovsky's "Sleeping Beauty Ballet" Songs George Bruns Erdman Penner Tom Adair Sammy Fain Winston Hibler Jack Lawrence Ted Sears Choral Arrangements John Karig Story Adaptation Erdman Penner From the Charles Perrault version of Sleeping Beauty Additional Story Joe Kinaldi Winston Hibler Bill Peet Ted Sears Ralph Wright Milt Banta Production Design Don Da Gradi Ken Anderson McLaren Stewart Tom Codrick Don Griffith Erni Nordli Basil Davidovich Victor Haboush Joe Hale Homer Jonas Jack Huber Kay Aragon Color Styling Eyvind Earle Background Frank Armitage Thelma Witmer Al Dempster Walt Peregoy Bill Layne Ralph Hulett HTTP://COPIONI.CORRIERESPETTACOLO.IT Dick Anthony Fil Mottola Richard H. -

Theme Parks: History, Art, Design • Alcorn, Steve

Theme Parks: History, Art, Design • Alcorn, Steve and David Green. Building a Better Mouse: The Story of the Electronic Imagineers Who Designed Epcot • Allan, Graham, Rebecca Cline, and Charlie Price. Holiday Magic at the Disney Parks: Celebrations Around the World from Fall to Winter • Baham, Jeff. The Unauthorized Story of Walt Disney’s Haunted Mansion • Ballard, Donald W. Disneyland Hotel 1954 – 1959: The Little Motel in the Middle of the Orange Grove • Ballard, Donald W. Disneyland Hotel: The Early Years, 1954 - 1988 • Bossert, David A. 3D Disneyland: Like You’ve Never Seen it Before • Bright, Randy. Disneyland: Inside Story • Broggie, Michael. Walt Disney’s Railroad Story: The Small-Scale Fascination That Led to a Full-Scale Kingdom • Dunlop, Beth. Building a Dream: The Art of Disney Architecture • Emerson, Chad. Project Future: The Inside Story Behind the Creation of Disney World • Fjellman, Stephen M. Vinyl Leaves: Walt Disney World and America • Goldberg, Aaron H. Buying Disney’s World • Goldberg, Aaron H. The Wonders of Walt Disney World • Gordon, Bruce and David Mumford. Disneyland: The Nickel Tour: A Postcard Journey Through a Half Century of The Happiest Place on Earth • Gordon, Bruce and Jeff Kurtti. The Art of Disneyland • Gordon, Bruce and Jeff Kurtti. The Art of Walt Disney World • Gordon, Bruce and Tim O’Day. Disneyland: Then, Now, and Forever • Gurr, Bob. Design: Just for Fun • Handke, Danny and Vanessa Hunt. Poster Art of the Disney Parks • Hench, John and Peggy Van Pelt. Designing Disney: Imagineering and the Art of the Show • Howland, Dan. Omnibus: The Journal of Ride Theory • Imagineers, The. -

Inspired by the Exciting Environments, Themes and Elemental Characters from Walt Disney Animation Studios' Frozen 2, Acclaimed

Inspired by the exciting environments, themes and elemental characters from Walt Disney Animation Studios’ Frozen 2, acclaimed director Jeff Gipson (Cycles) brings to life this imaginative and vibrant tale set in an enchanted forest outside of Arendelle. A family gathering for an evening of bedtime stories sets the stage for a magnificent adventure to a colorful and mythical world, which includes close encounters with the Nokk (a water spirit in the form of a mighty stallion), Gale (the playful wind spirit who can manifest as a light breeze or a raging tornado-like force), the Earth Giants (the massive creatures that form the rocky riverbanks and are capable of intense destruction when awakened), and the Fire Spirit (a fast-moving and mercurial salamander named Bruni). As the story unfolds, these spirits come to life and the myth of their past and future is revealed. Production designer Brittney Lee drew upon the Studios’ legacy of great artists (Eyvind Earle, Mary Blair, and Frozen’s own production designer Michael Giaimo) along with her own instincts to create a visual landscape that was unique in its colors, shapes and style. Just as Disney’s musical milestone, Fantasia, combined the power of music with striking visuals, producer Nicholas Russell and director Gipson, enlisted composer Joseph Trapanese (Tron: Legacy) to help them enhance the experience for Myth: A Frozen Tale. Evan Rachel Wood (the voice of Queen Iduna in Frozen 2) lends her voice as the narrator of the film. Finally, Myth is a tip of the hat to Gipson’s own family tradition of telling bedtime stories, including a particular story passed down from his great-great-great grandfather about a brush with the outlaw Jesse James when he was a young farm boy growing up near Kansas City. -

Audio-Animatronics ALL OTHER IMAGES ARE ©DISNEY

Introducing IEEE Collabratec™ The premier networking and collaboration site for technology professionals around the world. IEEE Collabratec is a new, integrated online community where IEEE members, Network. researchers, authors, and technology professionals with similar fields of interest can network and collaborate, as well as create and manage content. Collaborate. Featuring a suite of powerful online networking and collaboration tools, Create. IEEE Collabratec allows you to connect according to geographic location, technical interests, or career pursuits. You can also create and share a professional identity that showcases key accomplishments and participate in groups focused around mutual interests, actively learning from and contributing to knowledgeable communities. All in one place! Learn about IEEE Collabratec at ieee-collabratec.ieee.org THE MAGAZINE FOR HIGH-TECH INNOVATORS September/October 2019 Vol. 38 No. 5 THEME: WALT DISNEY IMAGINEERING The world of Walt Disney Imagineering 4 Craig Causer Disney tech: Immersive storytelling 10 through innovation Craig Causer ON THE COVER: Come take an inside look at Walt Big ideas: The sky’s the limit Disney Imagineering, where 19 creativity and technology converge Craig Causer to produce the magic housed within Disney parks and resorts. STARS: ©ISTOCKPHOTO/VIKTOR_VECTOR. Walt Disney Audio-Animatronics ALL OTHER IMAGES ARE ©DISNEY. 24 timeline Inside the minds of two of Imagineering’s 26 most prolific creative executives Craig Causer DEPARTMENTS & COLUMNS The wonder of Imaginations 3 editorial 35 Craig Causer 52 the way ahead 41 Earning your ears: The value of internships Sophia Acevedo Around the world: International parks MISSION STATEMENT: IEEE Potentials 44 is the magazine dedicated to undergraduate are distinctly Disney and graduate students and young profes- sionals.