Technologistview00joslrich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Wine Making in the Santa Cruz Mountains by Ross Eric Gibson

A History of Wine Making in the Santa Cruz Mountains By Ross Eric Gibson Santa Cruz was the birthplace of California's temperance movement. But beyond the whiskey-induced revelries of the county alcohol trade lies the more genteel history of the Santa Cruz County wine industry. Its saintly origin was the mission church itself, which planted its vineyards between 1804 and 1807 in what is now the Harvey West Park area. The fruits and vegetables imported by the mission were considered the best in the world, except for a variety called "mission grapes," which was unsuited to the cool, coastal climate. It produced an inferior, bitter wine, to which the padres added brandy, producing a very sweet "Angelica" wine. Between 1850 and 1880, loggers stripped 18 million board feet of lumber from the Santa Cruz Mountains, leaving large portions of cleared land. These were well-suited to fruit farmers, who favored grapes as the most adaptable to the limitations of mountain agriculture. Scotsman John Burns settled in the area in 1851, and in 1853 planted the first commercial vines in the county. Burns named the mountain where his vineyard grew "Ben Lomond" (meaning Mount Lomond), which was the name of an old wine district in Scotland. Meanwhile, brothers John and George Jarvis established a vineyard above Scotts Valley, in a place they named "Vine Hill." These became the two pillars of the county's wine industry, which by the turn of the century would emerge as dominant in the state. Santa Cruz became a third area, when Pietro Monteverdi and Antonio Capelli from the Italian wine district established the Italian Gardens as a vineyard district on what is now Pasatiempo Golf Course. -

Raleigh&Clarkes

6 HELEN A. WEEKLY HERALD. I LIST OF LETTERS Remaining in the Post Office at Helena, Lewis and Clarke County, Montana Territory, on the 17th day of November, 1880. When called for please say “advertised.” Allen Joe E .lardant Wm 2 Bronson E I) 2 Kelly Miss Paulin Reelle L Y 4 Kaigle Mrs M Boot and Shoe Boom RALEIGH&CLARKES Beebe Joseph H 2 Knoutton Chas Boner W A ' Kana Thos Bailey X ft Lewis Thomas Burgess W H I>aFore David E IN V IT E the «attention of Curtright J E Lindemutli F P WHY NOT P RALEIGH & CLARKES. Curtii Miss Mary I> Likins Levi the Trade to the fact that ,f Collins L M Lynch Michael w Cave Thomas Miller Miss Mary OUR WHOLESALE DEPART-: H E L E 1 V A . Carrier .Töseph B Moneberg Gus Cherry Daw , Matte Wm The Railroad is Within the Borders of Montana M ENT is unsually full and complete, j pRINTB DExiMft, c h e v io t s , Chambers II ft Merry Con (Conner Jno T Martin Mrs Relia Cameron .1 Meeks Miss Alice We keep all the Standard and Lead-1 TICKS, DRILLS, CASSIMERES, Day R A Olseri August Our Whole Country is in a Most Prosperous Condi , . ta p . i J YARNS, DUCKS, CAMBRICS Dorst Dock Peak Ed ft tion, and Trade is Brisk. in" Brands in Domestics. Freight England John Reynolds D L FLANNELS, CRASHES, BLANKETS. Farrel F Richards ft ft considered, our prices compare very BROw N AND BLEACHED c o tto n s. -

Wmmrwm.-- V S- -- Ip''' R Rthe " , DHL Jlr U JLJ JLJ JLJ X Llu Stibxcrtpllcin Kb

wmmrwm.-- v s- -- iP''' r rTHE " , DHL JLr U JLJ JLJ JLJ X llu Stibxcrtpllcin Kb. 2U. HONOLULU, II. I., SATURDAY, OCTOBER 7, 3882. 10 I'rnls nr .Month. THE DAILY BULLETIN Professionals. Is published every morning by the B. F. EHLERS & Co., Daily Hum.utin Puiimhiiixo Co., AUSTIN WHITING, Attorney nml cli (minted throughout thu town, mill W and Counsellor at Law. forwarded to the other Inlands by every DRY GOODS IMPORTERS, Agent to lake acknowledgments of opportunity. iiHlrumcnW. All Latost Novelties Fancy Goods Received by evory steamer, Kaahumanu St., Subscription, GO cts. per month. tho in Honolulu. 209 1 FORT STREET. G. Caiisok Ki:nyok, Editor. I.J J. M- - M0NSARRAT, v, All business communications to be nil. 'J. il'Jil 'LI'. .J. dressed, Manager Daily HMllctln, Post Commission Morchants. AT LAW and Notary Ofllcc Uo. No. 14. ATTOHEY J. G. Ci.r.vion, Manager. Oco. W. Maclarlaue! H. MacfiirTaiicl Heal Estate in any HONOLULU CLOTHING EMPORIUM, G. W. MAC7ARLANE & Co. part of the Kingdom bought, sold and leased, on The very latest teetotal drink up IMFOUTEHS, COMMISSION MKlt. CHANTS ami commission. Quccuslnml way is called "snnkc A. M. MELTjIS, Proprietor, Sityar factors, Loans negotiated, juice." It knocks Eli Johnson and FlrcProof Huildine;, 52 Queen street, Legal Documents Drawn. his drugs stiff in one net, and it is Importer and Dealer in Clothing, Honolulu. If. I. prepared as follows: Take seven AIIKNlfl for No. 27 Merchant St. (Gazette Hlock), 190 the deadliest Tim AVaikapu Sugar Fhintation, Maui, Honolulu, Hawaiian Island. snakes of sort, four Goods, Fancy Goods, tiic Spencer Sugar Plantation, Hawaii, death-adder- s, Dry and the inside parts of The uceia Suun'r Plantation, Oahu, DOLE, Lawyer and Notary Pub- - Mil), Maul, G cover with sul Huelo Suuar SH. -

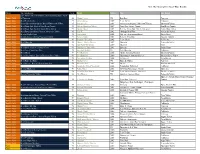

2018 the Toast of the Coast Wine Results

2018 The Toast of the Coast Wine Results Medal Special Awards Score Brand Vintage Wine Appellation THE TOAST OF THE COAST, Best Sparkling Rose, Best Double Gold of Carneros 96 Gloria Ferrer NV Brut Rosé Carneros Double Gold Best Petite Sirah 95 Vino Urbano 2015 Petite Sirah California Double Gold Best Cabernet Sauvignon, Best of Dry Creek Valley 95 Pedroncelli 2015 Cabernet Sauvignon, Block 007 Estate Dry Creek Valley Double Gold Best Pinot Gris, Best of San Diego County 95 Volcan Mountain Winery 2017 Pinot Gris, Estate Grown San Diego County Double Gold Best Pinot Noir, Best of Santa Maria Valley 95 Double Bond 2013 Reserve Pinot Noir, Toretti Vineyard Santa Maria Valley Double Gold Best Bordeaux Blend, Best of Alexander Valley 95 Cult X 2012 Meritage Red Wine Alexander Valley Double Gold Best of North Coast 95 Costa Azul 2014 Cabernet Sauvignon/Shiraz North Coast Double Gold Best Zinfandel, Best of Amador County 95 Sobon Estate 2015 ReZerve Primitivo Amador County Double Gold 94 Stanton Vineyards 2015 Petite Sirah St. Helena Double Gold Best Moscato 94 Maurice Car'rie Winery 2017 Moscato Temecula Valley Double Gold 94 Oak Farm Vineyards 2017 Albarino Lodi Double Gold Best Barbera, Best of South Coast 94 Old Survey Vineyards 2015 Barbera South Coast Double Gold Best Sweet Sparkling Wine 94 Barefoot Bubbly NV Pink Moscato California Double Gold Best Merlot 94 Frei Brothers 2015 Merlot, Sonoma Reserve Dry Creek Valley Double Gold Best Chardonnay, Best of Russian River Valley 94 Frei Brothers 2016 Chardonnay, Sonoma Reserve Russian River -

2011 Pinot Gris 2010 Tempranillo Tempranillo Braised Basque Short

OCCASIO AEGRE OFFERTUR, FACILE AMITTITUR. 2012AUTUMN IN THIS ISSUE NEW RELEASES 2011 Pinot Gris 2010 Tempranillo FEATURED RECIPE Tempranillo Braised Basque Short Ribs Welcome to our third anniversary issue of the Pocket Watch. It is hard to believe we are already here; only yesterday it seems we were hard at work placing the finishing touches on our grand opening. It was a time of anticipation; it was, however, gilded with an air of tension—would Livermore embrace a new style of winemaking devoted to the Valley’s storied past? I’m pleased to say the answer is yes. Residents, visitors and wine writers alike resonate with our mission to craft terroir-driven wines from our Valley’s heritage grapes. It is rewarding to us that nationally known wine reviewers like Virginie Boone and Anthony Dias Blue are noticing the historic essence of Livermore terroir in our wines. When Wine Enthusiast Magazine describes our Cabernet with “deep vein of minerality,” they are describing a feature of Livermore Valley wines prized a century ago by Wetmore, Bundschu, and Gier. With the advent of our third anniversary, our new release will be the 2010 Tempranillo and 2011 Pinot Gris. Tempranillo was a small player in the early days of this valley, introduced by Frederic Bioletti in 1905. The variety produced outstanding wine during Continued inside ... Occasio Winery–Honoring Livermore’s Heritage Varietals ...continued from front cover NEW RELEASES cool growing seasons—wines that rivaled the best of the Rioja. As 2010 was shaping up to be one of the coolest growing seasons on record, we made the decision in early July to harvest one ton of Tempranillo, making for an unusual Saturday harvest in the early morning on October 16th. -

It's the Beer Homer, GW, Salary Aa Dept Aur'veyor 75 Oo Coata in the Survey of the Kirkman Stipe, W

6 COLFAX GAZETTE. COLFAX, WASHINGTON, JULY 14, 1905. Squibb, R X, lodging and meals for Wade, G. W., labor 52 50 milt*Creek, about ouo mile below the indiganta 2 oo Walters, J. W. & Co., labor, $7; Pitt school house. Rose JewelryjStore Sturdivan, J M, labor on court house allowed 3 00 ; LETTERS M. A. COMMISSIONERS MIT grounds TWO OPEN 12 Oo Walters, J. W. A Co., repairs.. 275 \ The auditor was instructed to ad- KSTABLISHKI> IN IHH« Town of Colton, supplies for indigenta 550 Wateon, Virgil, labor 12 00 j vert iae for bids for the repairing of True, M C, expense as assessor 6 25 E. F., labor 10 00 IMfORTAHT TO MARRIED WOMEN . Pass on Bills and Claims and Trans- Wats. J C, labor on atone wall West, the following bridges: Codd bridge supplies West, J. H., labor 12 50 act Uthor Business Wheeler-Motter Co, for over the South Palouse river on Main Mary ofWashington tella county farm 12 16 Williams, Nate, supplies, $7.35; Mr*. Dlmmlck Weinburg, E W, wrvice as special allowed 5 35 street in Colfax, Wash. ; brewery How Lydla K. Pinknam's V»»«t»bl« ehentf $27.91, allowed. 21 oo Wright, W. F., labor 20 25 bridge over the north fork of the Compound Mftd*H«r Well. Official Proceeding of the Board of West, J H, arrest and expense for Yatee, Marcue, labor 33 00 6 Palouse river at the north end of County Commissioners of \V hu- sheriff 10 DISTRICT NO. 2 we publish Webster, J C, service as Bth grade Main street in Colfax, Wash. -

2018 International Port and Fortified Wine Competition Category List

2018 International Port and Fortified Wine Competition Category List Category # Fortified Wines Style Sub-Category PF100 Angelica Wine PF110 Buckfast Tonic (Caffeine) Bum Flavored Cisco (Sweet); Wild Russian Vanya; also Night Train, Thunderbird, Wild Irish Rose PF115 Commandaria PF120 Floc de Gascogne PF130 Ginger Wine PF135 Liqueur Muscat PF140 Macvin de Jura PF150 Madeira PF151 Madeira Sercial PF152 Madeira Verdeho PF153 Madeira Bual PF154 Madeira Malmsey PF155 Madeira Rainwater PF160 Malaga PF165 Marsala- Dry Style PF166 Marsala-Sweet PF170 Mavrodafni Dark PF171 Mistelle PF172 Muscat de Noel PF173 Muscatel White PF174 Pineau des Charentes White PF175 Pommeau Produced by Wine Country Network, Inc. Tel 303 664-5700 2018 International Port and Fortified Wine Competition Category List Port Wines (Portugal) PF200 Port (Portugal) PF205 Port (Portugal)-Ruby Port (Portugal) Tawny Indicated PF206 Age PF207 Port (Portugal) Tawny Colheita PF208 Port (Portugal) Tawny Crusted Port (Portugal) Vintage Garrafeira PF209 Port (Portugal) Reserve or Vintage PF210 Character Port (Portugal) Late Bottled Vintage PF211 PF212 Port (Portugal) Single Quinta PF213 White Port (Portugal) Leve Seco PF214 White Port (Portugal) Lagrima PF215 Rosé Port Rasteau (White, Rosé , Red)- PF 220 Rasteau AOC PF225 Rinquinquin (France) Produced by Wine Country Network, Inc. Tel 303 664-5700 2018 International Port and Fortified Wine Competition Category List Port-Style Wines (USA & Australia) Port Style Red Wine (not from PF230 Portugal) Port Style White Wine (not from PF235 Portugal) Flavored Port Style Wine (not from PF240 Portugal) Sherry (Spain) Sherry-Fino Manzanilla from PF250 Sanlucar PF251 Sherry-Pasada PF252 Sherry-Amontillada PF253 Sherry Fino from Jerez PF254 Sherry Fino-Amontillado PF255 Sherry Amontillado PF256 Sherry Palo Cortado PF257 Sherry Olorosa-Dry PF258 Sherry Olorosa-Sweet PF259 Sherry-Cream PF260 Sherry- Pale Cream PF261 Sherry-Sweet Pedro Zimenz Sherry- Moscatel Produced by Wine Country Network, Inc. -

Items 13 Reds Under $13 Arraez Bala Peridida Alicante Bouschet 13.00

Items 13 Reds Under $13 Arraez Bala Peridida Alicante Bouschet $ 13.00 Cellier Des Princes Aroma Syrah $ 9.00 Dow's Vale de Bomfim $ 12.00 Evolucio Blaufrankish $ 12.00 Monmousseau Chinon $ 11.00 Nicolas Idiart Pinot Noir $ 13.00 Pedrera Red Jumilla $ 8.00 Scaia Corvina $ 13.00 Terre del Tartufo Barbera $ 10.00 The Seeker Malbec $ 13.00 Tortoise Creek Cherokee Lane Cab $ 12.00 Vinicola Forno Beneventano Aglianico $ 9.00 13 Whites Under $13 Bonny Doon Gravitas White $ 9.00 Chateau La Freynelle Blanc $ 12.00 Dry Creek Chenin Blanc $ 13.00 Fina Grillo DOC Sicilia "Kebrilla" $ 13.00 Marotti Campi Verdicchio "Albiano" $ 12.00 Mayu Pedro Ximenez $ 13.00 Pelvas Brut Rose of Grenache $ 12.00 Piedra Negra Pinot Gris $ 13.00 S'Eleme Vermintino di Gallura DOCG $ 13.00 Skouras ZOE White $ 12.00 Vinicola Forno Falanghina Luna Turchese $ 10.00 Weingut Castelfeder Kerner 'Lahn' $ 13.00 Australian Reds Fowles Wines Ladies Who Shoot Their Lunch Shiraz $ 30.00 Misfits Wine Co Shiraz/Malbec $ 17.00 Red Bank Shiraz "The Long Paddock" $ 13.00 Some Young Punks passion has red lips $ 25.00 Australian Whites d"Arenberg "Hermit Crab" $ 17.00 Delinquente Screaming Betty Vermentino $ 20.00 Evans and Tate SB "Fresh as a Daisy" $ 15.00 Zonte's Footstep 'Excalibur' Sauvignon Blanc $ 19.00 Austrian Red Hermann Moser Zweigelt $ 17.00 Weingut Heinrich Neusiedlersee Red $ 17.00 Austrian Whites Page 1 Items Biokult Gruner Veltliner $ 13.00 Pfaffel Gruner Veltliner vom Haus $ 15.00 Wiengut Diwald Gruner Veltliner $ 18.00 From the Bar Menu Cleto Chiarli Vecchia Modena Lambrusco $ 14.00 Domaine Poulet et Fils Cremant de Die Brut $ 17.00 Fracchia Voulet Casorzo $ 13.00 Lucien Albrecht Cremant d'Alsace $ 20.00 Lustau Pedro Ximinez San Emilio $ 33.00 Mas Peyre Maury Hors D’Age “La Rage Du Soleil” $ 26.00 Vietti Moscato d'Asti $ 15.00 Xavier Vignon Muscat de Beaumes de Venise $ 25.00 Badenhorst "Secateurs Red" Blend $ 15.00 Bodegas Langa Pi Red $ 20.00 Cantina de Verona Amarone $ 28.00 Chateau Saint-Georges Bordeaux $ 35.00 Chave "Offerus" St. -

Thomas Urain Drills

8 COLFAX GAZETTE, COLFAX, WASHINGTON, SEPTEMBER 29, 1905. ROPY AND BITTER MILK. TWO FAMILY RESIDENCE. Both The«f < «tn«l i t ion w Are I'anally Modern Uonble lloaMe With Many \ Canned by Bacteria. Attractive Feature*— Cont, KIM:- o. A ropy milk is not always caused by LCopyright, ISOT>. by Stanley A. Dennis, 231 Broadway, New York ] bacteria, may come but it from the We show herewith elevation and Annual Fall Exposition animal suffering from certain diseases, floor plans for a model, low cost double particularly garget. In the majority house. This house may be erected on OF THE FASHIONABLE of cases the trouble is due to the de- a 37Vj foot lot, or larger, at au esti- Though not among the most sitlous velopment of bacteria subsequent to mated cost of $2,200. lliere Is a cel- of dairy troubles, "mottling" of butter the milking, says Hoard's Dairyman. lar under the entire house, with twelve Las perhaps been the cause of as much and eight inch walls, laid In cement Garment The cause of ropy milk can be traced Kaufman mortar. cc- discussion as any, says American Cul- to several species of bacteria, but the The cellar floor is also of For Men and Young Men tivator. The white streaks ami patches one that Is the most troublesome In mar the beauty of otherwise per- to be stylishly which the United States can be traced to an To those discriminating, economical Men and Young Men, who want fect butter do not affect Savor or uro- ?. or organism that is an Inhabitant of wa- at a cordial to view our tall display ina of the product, but they displease attired a moderate cost, we extend invitation the eye and thus lower the price. -

The Bancrof T Library University of ~Alifornia/~Erkeley Regional Oral History Office

The Bancrof t Library University of ~alifornia/~erkeley Regional Oral History Office California Wine Industry Oral History Prod ect Maynard A, Joslyn A TECHNOLOGIST VIEWS THE CALIFORNIA WINE INDUSTRY With an Introduction by Gordon Mackinney An Interview Conducted by Ruth Teiser Copy NO- @ 1974 by The Regents of the University of California All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the Regents of the University of California and Maynard A. Joslyn, dated April 1, 1974. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancrort Library of the University of California at Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, k86 Library, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The legal agreement with Maynard A. Joslyn requires that he be notified of the request and allowed thirty days in which to respond. TABLE OF CONTENTS -- Maynard A. Joslyn PREFACE INTRODUCTION by Gordon Mackinney INTERVIEW HISTORY INITIAL INTEREST IN WINE THE PROHIBITION PERIOD DIFFERING TASTES IN WINES THE POST-REPEAL INDUSTRY AND THE UNIVERSITY COOPERAGE AND EQUIPMENT PROBLEMS THE UNIVERSITY AND THE FEDERAL BANKS -

Grape Culture and Wine-Making in California

'a. i': '^^Z* .*)^J^ >< N.^ •\^ '^^ ^^.>-w- \f^^- ^ ^^. i %. J r^^ •' a ft ^ t^ ^ N C ^ ^^? *0 ,.0' ,/. "/'o. <' \\ . ^ 0^% :>^.v .0 o^ %^ ^*. "^^ ...^ % '< • :'i * '\ ..X: ^ * . Ukm CULTURE AND WINE-MMIM IN CALIFORNIA • A PKACTICAL^MANUAL FOR THE GRAPE-GROWER AND WINE-MAKER BY ^ i GEORGE HUSMANN NAPA, CAL SAN FRANCISCO PAYOT, UPHAM & CO., PUBLISHERS 204 Sansome Street 1888 Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1887, by PAYOT, UPHAM & COMPANY In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington COMMERCIAL PUBLISHING COMPANY PRINTERS 34 CALIFORNIA STREET, S. F PREFACE. A book, specially devoted to "Grape Culture and Wine Making in California," would seem to need no apology for its appearance, however much the author may do so for under- taking the task. California seems to him, at least, as ''the chosen land of the Lord," the great Vineland ; and the in- dustry, now only in its first stages of development, destined to overshadow all others. It has already assumed dimensions, within the short period of its existence, hardly forty years, that our European brethren can not believe it, and a smile of incredulity comes to their lips when we speak of vineyards of several thousand acres, with a product of millions of gallons per annum. But, while fully cognizant of the importance of these large enterprises, it is not for their owners that this little volume is Avritten specially. The millionaire who is able to plant and maintain a vineyard of several thousand acres, can and should provide the best and most scientific skill to manage his vine- yard and his cellars; it will be the wisest and most economi- cal course for him, he can afford to pay high salaries, and the most costly wineries, provided they are also practical, would be a good investment for him. -

May 2018 Newsletter

May 2018 Articles: President’s Message . President’s Message Hello Dear CellarMasters, rd • Calendar of Our May 3 meeting at the shop is being organized by Acting President Michael Events and Holland and he will conduct barrel (or carboy etc.) sampling. Bring a sample of Meetings. some of your wine you’d like some feedback on before you go to bottling or blending. • Monthly Meeting Be sure to RSVP for May 5th’s Derby Day right away – seating is limited. It’s my May 3rd favorite day of the year so I want everyone there to play with! Potluck theme: Mexican Food Our planning party will be graciously held at the home of Michael Holland & Anne th For Sale Louise Bannon on Thursday, May 10 . Remember, we are invited into fellow member’s homes and we ask everyone to be respectful of their home and time. The planning party meeting will begin at 7pm and end at 9:30pm. I hope to see you all at least three times this May! Elissa Rosenberg, President We’re on the Web! See us at: http://cellarmastersla.org/ CELLARMASTERS DERBY DAY SATURDAY, MAY 5TH See flyer page 6 Don’t Forget to Like Us on FACEBOOK Cellarmasters LA 2 Planning Meeting Minutes—April 12, 2018 Attendees: Gregg Smith, Bruce and Dee Dee, Tom,Renee, ownership of the media system, Nancy seconds. Vote: yea 11 Nancy, Dave, Mike H, Elissa, Matt, Lynda opposed 0. Prez Report: Elissa Rosenberg Derby Days. A fourth home is to be added to the schedule at Thanks to Fred and Lisa for the tasting party Will Scout’s home.