Download This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wanted Laborers Artificial Limb Co

INFORMATION SWOLLEN (Varicose) VEINS DEPARTMENT Are painful and often dangerous. Our Commercial Information furnished free or cnarge. cataioguea supplied and com Elastic Stockings, Belts merciai inquinea cheerfully answered. and Bandages always give relief. Write any firm below Do It now! Pleeae Mentloa ThU Ppr Whaa limrin Thaw Ad.irtiKBMU. Fitters and Makers for Twenty-fiv- e Years ART LEATHER GOODS If you Must sell your LIBERTY or VICTORY Leather Leggins, Traveling Bags, Trunks, bonds sell to us. If you can buy more LIBERTY Satisfaction or Money Back. .ceiia. roruana Leather Co. or VICTORY zzo wasmngton BONDS bonds buy from us. We buy and sell Sendfor Book and Measure Blank Today, ARTIFICIAL TEETH SPECIALIST " at the New York market Dr. E. C. Rossman, 367 Journal Bldg. GOVERNMENT AND lUHNiriPAi WOODWARD, CLARKE & CO. 1H1 untune AUTOMATIC SEALING VAULT Write for deicrlptlve circular and booklets. Linnton, Or. Further Information address a package Woodtark Building Alder at West Park C. W. Goodsman. (J MORRIS BROTHERS, Inc., BOILER WORKS New ReDalrlna Morrl. Building, 309-1- East Wks, & Stark Street PORTLAND. OREGON Side Boiler East Water Main BRAZING, WELDING ft CUTTING. USED CARS Northwest Welding & Supply Co., 38 1st St Deiore tne war At neuig i heater, Portland, Uregon Whether you get good value for th BUTTER FAT BOUGHT lVsfVmVIU fflf'llVAV.U! Three Night., Sun. Mon. Tu... money invested in a used car, in our Fernwood Dairy pays cash for butterfat Four Matiueei: Sun. Mon. Tue.. Wed. opinion, depends entirely on the amount CREAMERY iTfaataiiaaI UMlWro Ctltcuftl MATINEES 1 5c to 75c. NlGHTS-1- 5c to $1.25 ot money you are required to spend to Willamette Dairy, Buyers of Milk, Cream put your ear in satisfactory condition. -

References and Video Script

Portland State University PDXScholar Ernie Bonner Collection Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 1-1-1980 References and video script Ernest Bonner Gregg Kantor Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_bonner Part of the Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bonner, Ernest and Kantor, Gregg, "References and video script" (1980). Ernie Bonner Collection. 305. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_bonner/305 This Note is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ernie Bonner Collection by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pioneer Courthouse Square "The Portland Hotel. Hostelry Arose From Abandoned Foundation." April 4, 1984. "Own a share of your square," Jonathan Parry Nicholas, Downtowner, April 6, 1981 "Historian Finds Square Unique Urban Project," E. Kimbark MacCall, Old Portland Times, April 4, 1984. "At the time of its initial planning six years ago (1978), the 200 foot square city block was valued at $3 Million—the most expensive piece of real estate in Portland—quite an appreciation from its 1849 selling price of $24." "Portland Celebrates! Completion of Courthouse Square Marks Urban Renewal Area. April 6th Historic Date for Central City Block;" Old Portland Times, April 4, 1984. "The April 6th date [for the opening of the Square] also marks the 133rd anniversary of Portland's incorporation as a city, the 94th anniversary of the opening of the Portland Hotel that stood on the site from 1890 to 1951, and the birthday of the Square's architect, Willard Martin of Portland." ".. -

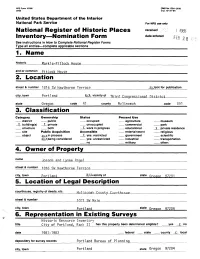

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received r3 ! I985 Inventory—Nomination Form oawemereudate entered FEB ? £« \j See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections____________________________________ 1. Name historic Markle-Pittock House and or common pjttock House 2. Location street & number 1816 SW Hawthorne Terrace for publication city, town Portland state Oregon code 41 county Multnomah code 051 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both _ X_ work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object -j^t£ in process _ X_ yes: restricted government scientific 4^, being considered _ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name and I ynne Angel street & number 1fl16 S y Havithnrne Tprrar.e city, town Portland JL/Avicinity of state QreaQn 07201 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Multnornah County Courthosue street & number m?1 SW Main city, town Portland state Qreaon 972Q4 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Historic Resource Inventory title City Of Portland, Rank II has this property been determined eligible? yes X no date 1981-1983 federal state county local depository for survey records Portland Bureau of Planning__ city, town Portland state Oregon 97204 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered _X_ original site -Xgood ruins _X_ altered moved date N/A fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Markle-Pittock House, whose construction was begun in 1888, was once considered the largest and most prominently sited residence in the city. -

2016 Portland Hotel Guide

Portland Hotel Guide HouseSpecial 2016 housespecial.com Airport 12 420 NE 9th Ave. 10 2 11 8 7 4 3 6 1 5 9 North WELCOME TO PORTLAND Here are some hotel suggestions for your stay. Hopefully, this will give you a little taste of the city and make your decision a bit easier. We know you’re going to love Portland — we sure do. 1 The Nines HOUSESPECIAL RATE HOTELS 2 Ace Hotel The Nines .....................................................................page 3 3 Hotel Lucia Ace Hotel .....................................................................page 4 4 Hotel deLuxe Hotel Lucia ...................................................................page 5 Hotel deLuxe ................................................................page 6 5 Hotel Monaco Hotel Monaco...............................................................page 7 Sentinel Hotel ..............................................................page 8 6 Sentinel Hotel Hotel Vintage ...............................................................page 9 7 Hotel Vintage Hotel Eastlund..............................................................page 10 8 Benson Hotel 9 The Heathman Hotel STANDARD RATE HOTELS Benson Hotel ...............................................................page 11 10 Jupiter Hotel The Heathman .............................................................page 12 11 The Westin Jupiter Hotel ................................................................page 13 The Westin ...................................................................page 14 12 Hotel -

2019 Downtown Hotel Density

HANCOCK S.T UPSHUR ST. SCHUYLER S. T . A VE T. FLINT AVE. THURMAN S WILLIAMS AVE. VANCOUVER 15TH AVE. 16TH AVE. 14TH AVE. 2ND AVE. 3RD AVE. 9TH AVE. 8TH AVE. 6TH AVE. 1ST AVE. 13TH AVE. 12TH AVE. 10TH AVE. 7TH AVE. 11TH AVE. THURMAN ST. VICTORIA AVE. BROADWAY ST. T WHEELER . VE DIXON S A SA VIER ST. ROSS ROSS MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. BLVD. VE A WEIDLER S.T . A VE RALEIGH ST. BENTON LARRABEE LARRABEE HALSEY S.T QUIMBYT S . WINNING AVE. CLACKAMAS S. T PETTYGROVE ST. WASCO S.T GRAND T . OVER TON S VE A TE TE T A MULTNOMAH ST. INTERS NOR THRUP ST. STREETCA R HASSALO S.T MARSHALL ST. 1ST AVE. WHEELER AVE. ATION WAY ATION T S HOLLADAY ST. 225 T . STREETCA LOVEJOY S R PACIFIC S.T KEARNEY ST. 2019 Marriott Residence Inn OREGON S.T T . VE. JOHNSON S A 6TH 6TH IRVING ST. ARKWAY P T . VING S NAITO IR L VD VE. VE. A VE. HOYT ST. VE. VE. A LLOYD B A A A VE. A 15TH 15TH 16TH 16TH 17TH 17TH 18TH 18TH 19TH 19TH HOYTT S . 23RD 23RD GLISAN S.T Canopy Hilton GLISANT S . 25 Harlow Hotel Hampton Inn 153 FLANDERS S. T FLANDERS ST. Society Hotel Total Room Count: 6,819 Room Total EVERETT S. T 243 VE. T. AVE. AY EVERETT S VE. A VE. W VE. A A VE. A VE. VE. VE. VE. A VE. VE. A A A 62 VE. A A 3RD 3RD A A 4TH 4TH 5TH 5TH DAVIS ST. -

Cornerstones of Community: Building of Portland's African American History

Portland State University PDXScholar Black Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations Black Studies 8-1995 Cornerstones of Community: Buildings of Portland's African American History Darrell Millner Portland State University, [email protected] Carl Abbott Portland State University, [email protected] Cathy Galbraith The Bosco-Milligan Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/black_studies_fac Part of the United States History Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Millner, Darrell; Abbott, Carl; and Galbraith, Cathy, "Cornerstones of Community: Buildings of Portland's African American History" (1995). Black Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations. 60. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/black_studies_fac/60 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Black Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. ( CORNERSTONES OF COMMUNITY: BUILDINGS OF PORTLAND'S AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY Rutherford Home (1920) 833 NE Shaver Bosco-Milligan Foundation PO Box 14157 Portland, Oregon 97214 August 1995 CORNERSTONES OF COMMUNITY: BUILDINGS OF PORTLAND'S AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY Dedication This publication is dedicated to the Portland Chapter ofthe NMCP, and to the men and women whose individual histories make up the collective history ofPortland's -

Road to Oregon Written by Dr

The Road to Oregon Written by Dr. Jim Tompkins, a prominent local historian and the descendant of Oregon Trail immigrants, The Road to Oregon is a good primer on the history of the Oregon Trail. Unit I. The Pioneers: 1800-1840 Who Explored the Oregon Trail? The emigrants of the 1840s were not the first to travel the Oregon Trail. The colorful history of our country makes heroes out of the explorers, mountain men, soldiers, and scientists who opened up the West. In 1540 the Spanish explorer Coronado ventured as far north as present-day Kansas, but the inland routes across the plains remained the sole domain of Native Americans until 1804, when Lewis and Clark skirted the edges on their epic journey of discovery to the Pacific Northwest and Zeb Pike explored the "Great American Desert," as the Great Plains were then known. The Lewis and Clark Expedition had a direct influence on the economy of the West even before the explorers had returned to St. Louis. Private John Colter left the expedition on the way home in 1806 to take up the fur trade business. For the next 20 years the likes of Manuel Lisa, Auguste and Pierre Choteau, William Ashley, James Bridger, Kit Carson, Tom Fitzgerald, and William Sublette roamed the West. These part romantic adventurers, part self-made entrepreneurs, part hermits were called mountain men. By 1829, Jedediah Smith knew more about the West than any other person alive. The Americans became involved in the fur trade in 1810 when John Jacob Astor, at the insistence of his friend Thomas Jefferson, founded the Pacific Fur Company in New York. -

Northwest Trails Newsletter of the Northwest Chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association

Northwest Trails Newsletter of the Northwest Chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association Volume 32, No. 3 Summer 2017 NW OCTA Annual Fall Picnic Saturday, September 23, 9:00 a.m. – 3:00 p.m. Clark County Genealogical Society Annex 715 Grand Blvd., Vancouver, Washington The chapter’s annual fall event will again be held this year at the Clark County Genealogical Society Annex in Vancouver, WA. The event will begin at 9:00 a.m. with a coffee hour, and the meeting will begin at 10:00. We will include a chapter meeting, a recap of this year’s events, and discussion of other important issues for the coming year. Pre-registration is not necessary. Be prepared to pay $10 at the door to cover space rental and other picnic expenses. Bring your own picnic lunch. This is not a potluck. Bring a dessert for the dessert table. The chapter will furnish coffee and tea. Soft drinks will be available for a small donation. Raffle and Silent Auction. Please bring items you think would make good raffle or silent auction contribution. Please bundle magazines into sets of at least a year. Program Highlights: Shirlee Evans, member and author, will explain her two new historical fiction books—Their Troubled Trails and No Belonging Place—and have copies for sale. After lunch, there will be reports by the different committee leaders. Other board issues will be discussed. Directions and parking: From I-5. Take exit 1-C (Mill Plain Exit) and drive east on Mill Plain about 1.5 miles to Grand Blvd. -

Midtown Blocks Historic Assessment September 2004

Midtown Blocks Historic Assessment September 2004 Acknowledgements Portland Bureau of Planning Vera Katz, Mayor Gil Kelley, Planning Director Project Staff Joe Zehnder, Principle Planner Steve Dotterrer, Principle Planner Julia Gisler, City Planner II Cielo Lutino, City Planner II Lisa Abuaf, Community Service Aide With Additional Assistance From: Donah Baribeau, Office Specialist III Gary Odenthal, Technical Service Manager Carmen Piekarski, GIS Analyst Urban Design Section Portland Development Commission Amy Miller Dowell, Senior Project Coordinator Historic Research Consultant Donald R. Nelson, Historic Writing and Research Cover Images (clockwise from top left): Guild Theatre Marquee, 2003; SW Salmon & Broadway, ca. 1928; Drawing of the Pythian Building, 1906; SW 9th & Yamhill, 2003; Entrance to the Woodlark Building, 2003; Virginia Café Neon, 2003; Fox Theater and Music Box, 1989; Demolition of the Orpheum Theater, 1976; Construction of the Benson Hotel, 1912; Stevens Building, 1914; Broadway Building and Liebes Building, 2003. Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................. 1 Recent Planning for the Midtown Blocks ........................................ 1 Historic Assessment ................................................................ 1 Elements of the Historic Assessment............................................. 2 Findings ............................................................................... 4 Recommendations.................................................................. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form IIWRF

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form IIWRF ' Wsi^R?'^":.;aCESj This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. see^4^^i^laij|^tt|(SoCojiplete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classifications, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Swetland Building other names/site number 2. Location street& number 500 SW 5tn Avenue O not for publication city or town __ Portland '-' vicinity state Oregon code OR county Multnomah code 51 zip code 97205 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X_____ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property b£>ecjJ6idered significant __ nationally __ statewide X locally. -

In Portland, Oregon, a New Generation of Chefs and Producers Are Serving

In Portland, Oregon, a new generation of chefs and producers are serving up local food that combines creative flair COUNTER with a sense of community Words Claire Nelson Photography Dave Lauridsen CULTURE 84 jamiemagazine.com jamiemagazine.com 85 Left: The sprawling Forest with one of his rooftop Park. Opposite, clockwise hives; grilled octopus at from top left: Tyler Malek Tasty n Alder. Previous serves up ice creams at spread: Ryan and Jace in Salt & Straw; watermelon their food truck, Fried Egg salad, with Jacobsen sea I’m in Love; a dad takes a salt, at Imperial; Bee coffee break at Cup & Bar. Local’s Damian Magista the hipsters, the hikers, the artists and – perhaps gathering most momentum – the foodies. This leafy metropolis has become THE place to eat – a culinary hotspot, thanks largely to its location in bountiful northern Oregon. The state’s wet winters and balmy summers nurture a boggling variety of produce, including meat and crops from the rugged plains out east, and ample seafood from the Pacific to the west. What doesn’t grow here, friendly neighbour California generously supplies. It’s no surprise that chefs and producers are heading to Portland to make their mark. It’s like a throwback to the pioneering spirit of the Oregon Trail era, when Americans packed their covered wagons and rolled on out here in search of greener pastures. These days, the wagons have given way to food trucks, now numbering more than 600, and the burgeoning street-food scene is now embraced as part of the city’s culture. -

Pioneer Courthouse Square Project Funding

Portland State University PDXScholar Portland City Archives Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 1-1-1978 Pioneer Courthouse Square Project Funding Portland (Or.). Development Commission Portland (Or.). Bureau of Planning Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityarchives Part of the Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Portland (Or.). Development Commission and Portland (Or.). Bureau of Planning, "Pioneer Courthouse Square Project Funding" (1978). Portland City Archives. 98. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityarchives/98 This Ephemera is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Portland City Archives by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. - CHRONOLOGY PIONEER; COURTHOUSE SQUARE - HISTORY OF INCREASED VALUE 6-27-78 Dave Hunt left materials on an expanded program and increased costs with H.C.R.S. in Washington, D.C. Bob Ritsch was not available for the scheduled meeting. The materials did not indicate an increase in cost of the land. 7-26-78 Letter Secretary Andrus to Mayor. Acknowledged Hunt's visit and advised processing amendment through Dave Talbot. 10-30-78 Meeting Mike Cook (PDC) and Gary Scott (State Recreation Director). Complete program and project budget were discussed including the proposed land value increase. Scott suggested it might be possible to allow for the donation without an actual offer to May Company. 11-9-78 Meeting - Dave Talbot (State Parks Superintendent), Maurice Lundy (H.C.R.S.