1 Interview with Barbara Dane and Irwin Silber of Paredon Records

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Issue 510 Bud & Broadway on the Move Taking a Morning Show on a Remarkable Journey from Market No

August 1 2016, Issue 510 Bud & Broadway On The Move Taking a morning show on a remarkable journey from market No. 188 to No. 22 was all part of the five- (and-a-half) year plan for WIL/St. Louis’ Bud & Broadway. Of course, their decades of programming and on-air experience helped. Country Aircheck reached out for a travelogue. In 2010, WTVY/Dothan, AL PD Jerry Broadway brought in Bud Ford for afternoons. “After he and I met and started hanging out, we figured out pretty quick that we should be doing a morning show together,” says Broadway. “I was already on the morning show, and an opportunity came up to add a partner, and I decided Bud was going to be that guy.” Don’t Be Your Own Boss: The two tapped prodigious programming experience – Ford’s includes WKDF/Nashville – and aimed to create a show either would hire. Easier said than done, Flatts Forward: Big Machine’s Rascal Flatts in Dallas Saturday it turns out. “It challenges us,” says Ford. “There are two sides. (7/30). Pictured are (back, l-r) KPLX’s Mark Phillips, RF’s Jay The thing that makes you DeMarcus, KPLX & KSCS’ Mac Daniels, RF’s Gary LeVox, KPLX’s great at being a PD kills Victor Scott, RF’s Joe Don Rooney, KSCS’ Connected K and KPLX’s your ability to be on air, Skip Mahaffey; (front, l-r) KPLX & KSCS’ Rebecca Kaplan, KSCS’ because the on-air portion Trapper John Morris and Big Machine’s Alex Valentine. has got to be what we call unpredictable predictability. -

Diana Davies Photograph Collection Finding Aid

Diana Davies Photograph Collection Finding Aid Collection summary Prepared by Stephanie Smith, Joyce Capper, Jillian Foley, and Meaghan McCarthy 2004-2005. Creator: Diana Davies Title: The Diana Davies Photograph Collection Extent: 8 binders containing contact sheets, slides, and prints; 7 boxes (8.5”x10.75”x2.5”) of 35 mm negatives; 2 binders of 35 mm and 120 format negatives; and 1 box of 11 oversize prints. Abstract: Original photographs, negatives, and color slides taken by Diana Davies. Date span: 1963-present. Bulk dates: Newport Folk Festival, 1963-1969, 1987, 1992; Philadelphia Folk Festival, 1967-1968, 1987. Provenance The Smithsonian Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections acquired portions of the Diana Davies Photograph Collection in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Ms. Davies photographed for the Festival of American Folklife. More materials came to the Archives circa 1989 or 1990. Archivist Stephanie Smith visited her in 1998 and 2004, and brought back additional materials which Ms. Davies wanted to donate to the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives. In a letter dated 12 March 2002, Ms. Davies gave full discretion to the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage to grant permission for both internal and external use of her photographs, with the proviso that her work be credited “photo by Diana Davies.” Restrictions Permission for the duplication or publication of items in the Diana Davies Photograph Collection must be obtained from the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections. Consult the archivists for further information. Scope and Content Note The Davies photographs already held by the Rinzler Archives have been supplemented by two more recent donations (1998 and 2004) of additional photographs (contact sheets, prints, and slides) of the Newport Folk Festival, the Philadelphia Folk Festival, the Poor People's March on Washington, the Civil Rights Movement, the Georgia Sea Islands, and miscellaneous personalities of the American folk revival. -

STREETS Ramblinʻ' BOYS

Revue de Musiques Américaines 135 LELE DUDU COYOTECOYOTE Août-Septembre 2013 5 Frank SOLiVAN & DiRTY KiTCHEN Thomas HiNE Good Rockinʻ Tonight STREETSSTREETS RAMBLiNʻRAMBLiNʻ BOYSBOYS Les tribulations de Derroll Adams et Jack Elliott en Europe Avenue Country - Bluegrass & C° - Scalpel de Coyote - Kanga Routes - Crock ‚nʻ Roll - Noix de Cajun Plume Cinéma - Coyote Report - DisquʻAirs - Concerts & Festival - Cabas du Fana - Ami-Coyote Alain Avec la collaboration de FOURNiER STREETS RAMBLiN' BOYS Danny Adams et Anne Fournier Les tribulations de Derroll Adams et Jack Elliott sur les routes dʼEurope L'histoire vraie de deux faux cow-boys faisant irruption sur le Vieux Continent qui découvre la musique folk américaine. L’arrivée de Jack Elliott et Derroll Adams dans le Londres des années 50 déclenche un engouement pour cette musique, précédant le «folk revival» commercial pratiqué par les Brothers Four, le Kingston Trio ou Peter Paul & Mary. Après Paul Clayton et Alan Lomax, les deux troubadours sont les principaux artisans de cette éclosion. Ils font découvrir Woody Guthrie dans les rues, les clubs et aux terrasses des cafés, d’abord à Londres puis à Paris, à Milan et dans l’Europe entière. Derroll et son banjo influencent de jeunes musiciens comme Donovan, Youra Marcus, Gabriel Yacoub (fondateur de Malicorne) ou Tucker Zimmerman qui écrivit pour lui l’immortel Oregon. Jack est le chaînon manquant entre Woody Guthrie, le "Dust Bowl Troubadour" et Bob Dylan : dans la famille Folk on connaît Woody, le grand-père engagé, et Bob le petit-fils rebelle, mais on oublie trop souvent l’oncle Jack, infatigable trimardeur au service de la musique populaire. -

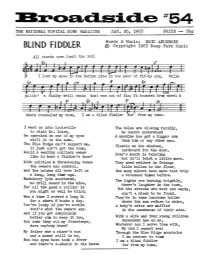

BLIND FIDDLER © Copyright 1965 Deep Fork Husic

c:l.si THE NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG MAGAZINE JAN. 20, 1965 PRICE -- 50¢ Words & Music: ERIC ANDERSEN BLIND FIDDLER © Copyright 1965 Deep Fork Husic All chords open (omit the 3rd) there concealed my doom, I am a blind fiddler . ar from my home. I went up into Louisville The holes are closing rapidly, to visit Dr. Laine, he cannot understand He operated on one of my eyes A machine has got a bigger arm still it is the same. than him or ~ other man. The Blue Ridge can't support me, Plastic on the ,windows, it just ain't got the room, cardboard for the door, Would a wealthy colliery owner Baby's mouth is twisting like to hear a fiddler's tune? but it'll twist a little more. With politics & threatening tones They need welders in Chicago the owners can control, falls hollow to the floor, And the unions all have left us How many miners have made that trip a long, long time ago. a thousand times before. Machinery ~in scattered, The lights are burning brightly, nCOJ drill sound in the mine, there's laughter in the town, For all the good a collier is But the streets are dark and empty, you might as well be blind. ain I t a miner to be found. Was a time I worked a long 14 They're in some lonesome holler for a short 8 bucks a day. where the sun refuse to shine, You I re lucky if you're workin A baby's cries are muffled that's what the owners say. -

Collection Highlights

COLLECTION HIGHLIGHTS “LATINOS AND BASEBALL” COLLECTING INITIATIVE Latino baseball players have been interwoven in the fabric of Major League Baseball for years. They've been some of the greatest, well-known names in baseball history. To reflect and celebrate that rich history, the National Museum of American History (“NMAH”) in collaboration with the Smithsonian Latino Center, launched Latinos and Baseball: In the Barrios and the Big Leagues. The multi-year community collecting initiative focuses on the historic role that baseball has played as a social and cultural force within Latino communities across the nation. The project launched a series of collecting events in late February in San Bernardino, California. A second event will be held in Los Angeles on July 17, 2016, and a third will be held in Syracuse, New York, on September 15, 2016. The events are designed to generate interest in the initiative, build on community relationships, record oral histories, and identify objects for possible acquisition by local historical associations as well as for the Smithsonian collections. The collaborative initiative seeks to document stories from across the U.S. and Puerto Rico and plans to collect a number of objects that could include baseball equipment; stadium signs; game memorabilia, such as handmade or mass-produced jerseys and tickets; food vendor signs; home movies; and period photographs. Curators will select objects based on the stories they represent and the insight they provide into the personal, community, and national narratives of the national pastime. “Baseball has played a major role in everyday American life since the 1800s, providing a means of celebrating both national and ethnic identities and building communities,” said John Gray, director of NMAH. -

Welcomed by 97.5 Y Country and Presented by United Federal Credit Union

Welcomed by 97.5 Y Country and presented by United Federal Credit Union, Wednesday, August 15, will feature hit country duo, LOCASH! LOCASH is a Country music duo made up of singer-songwriters Chris Lucas and Preston Brust, natives of Baltimore, Maryland, and Indianapolis, Indiana, respectively. With a sound that fuses modern Country and classic heartland Rock with an edgy vocal blend, the independently-minded partners are revered as “one of Nashville’s hardest-working acts” (Rolling Stone) whose live show “has consistently been among the most energetic and entertaining in the country music genre” (Billboard). With two albums and eight charting singles to their credit, LOCASH broke out in 2015 with their gracious GOLD-certified hit, “I Love This Life," followed by the flirtatious GOLD-certified #1 smash, “I Know Somebody” – their first trip to the top of the Country radio airplay charts – and 2017’s fun-loving romantic anthem “Ring on Every Finger.” All three singles were part of their Reviver Records album debut, THE FIGHTERS, which was released in the summer of 2016 to Top 15 success. The follow up to THE FIGHTERS is expected in 2018, with the forthcoming album’s first single “Don’t Get Better Than That” available now on all digital platforms. As songwriters, Lucas and Brust have scored two undeniable hits (Keith Urban’s #1 “You Gonna Fly” in 2011 and Tim McGraw’s PLATINUM-certified “Truck Yeah” in 2012). Currently nominated for Vocal Duo of the Year and New Vocal Duo or Group of the Year at the upcoming ACM Awards, they previously scored nominations at the CMT Music Awards and CMA Awards in 2017. -

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Title 11Th Street Waltz Sean Mcgowan Sean

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Title Title Creator(s) Arranger Performer Month Year 101 South Peter Finger Peter Finger Mar 2000 11th Street Waltz Sean McGowan Sean McGowan Aug 2012 1952 Vincent Black Lightning Richard Thompson Richard Thompson Nov/Dec 1993 39 Brian May Queen May 2015 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover Paul Simon Paul Simon Jan 2019 500 Miles Traditional Mar/Apr 1992 5927 California Street Teja Gerken Jan 2013 A Blacksmith Courted Me Traditional Martin Simpson Martin Simpson May 2004 A Daughter in Denver Tom Paxton Tom Paxton Aug 2017 A Day at the Races Preston Reed Preston Reed Jul/Aug 1992 A Grandmother's Wish Keola Beamer, Auntie Alice Namakelua Keola Beamer Sep 2001 A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall Bob Dylan Bob Dylan Dec 2000 A Little Love, A Little Kiss Adrian Ross, Lao Silesu Eddie Lang Apr 2018 A Natural Man Jack Williams Jack Williams Mar 2017 A Night in Frontenac Beppe Gambetta Beppe Gambetta Jun 2004 A Tribute to Peador O'Donnell Donal Lunny Jerry Douglas Sep 1998 A Whiter Shade of Pale Keith Reed, Gary Brooker Martin Tallstrom Procul Harum Jun 2011 About a Girl Kurt Cobain Nirvana Nov 2009 Act Naturally Vonie Morrison, Johnny Russel The Beatles Nov 2011 Addison's Walk (excerpts) Phil Keaggy Phil Keaggy May/Jun 1992 Adelita Francisco Tarrega Sep 2018 Africa David Paich, Jeff Porcaro Andy McKee Andy McKee Nov 2009 After the Rain Chuck Prophet, Kurt Lipschutz Chuck Prophet Sep 2003 After You've Gone Henry Creamer, Turner Layton Sep 2005 Ain't It Enough Ketch Secor, Willie Watson Old Crow Medicine Show Jan 2013 Ain't Life a Brook -

May 1965 Sing Out, Songs from Berkeley, Irwin Silber

IN THIS ISSUE SONGS INSTRUMENTAL TECHNIQUES OF AMERICAN FOLK GUITAR - An instruction book on Carter Plcldng' and Fingerplcking; including examples from Elizabeth Cotten, There But for Fortune 5 Mississippi John Hurt, Rev. Gary Davis, Dave Van Ronk, Hick's Farewell 14 etc, Forty solos fUll y written out in musIc and tablature. Little Sally Racket 15 $2.95 plus 25~ handllng. Traditional stringed Instruments, Long Black Veil 16 P.O. Box 1106, Laguna Beach, CaUl. THE FOLK SONG MAGAZINE Man with the Microphone 21 SEND FOR YOUR FREE CATALOG on Epic hand crafted 'The Verdant Braes of Skreen 22 ~:~~~d~e Epic Company, 5658 S. Foz Circle, Littleton, VOL. 15, NO. 2 W ith International Section MAY 1965 75~ The Commonwealth of Toil 26 -An I Want Is Union 27 FREE BEAUTIFUL SONG. All music-lovers send names, Links on the Chain 32 ~~g~ ~ses . Nordyke, 6000-21 Sunset, Hollywood, call!. JOHNNY CASH MUDDY WATERS Get Up and Go 34 Long Thumb 35 DffiE CTORY OF COFFEE HOUSE S Across the Country ••• The Hell-Bound Train 38 updated edition covers 150 coffeehouses: addresses, des criptions, detaUs on entertaInment policies. $1 .00. TaUs Beans in My Ears 45 man Press, Boz 469, Armonk, N. Y. (Year's subscription Cannily, Cannily 46 to supplements $1.00 additional). ARTICLES FOLK MUSIC SUPPLIE S: Records , books, guitars, banjos, accessories; all available by mall. Write tor information. Denver Folklore Center, 608 East 17th Ave., Denver 3, News and Notes 2 Colo. R & B (Tony Glover) 6 Son~s from Berkeley NAKADE GUITARS - ClaSSical, Flamenco, Requinta. -

The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributions and Contradictions Author(S): Jens Lund and R

The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributions and Contradictions Author(s): Jens Lund and R. Serge Denisoff Source: The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 84, No. 334 (Oct. - Dec., 1971), pp. 394-405 Published by: American Folklore Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/539633 . Accessed: 22/09/2011 16:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Folklore Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of American Folklore. http://www.jstor.org JENS LUND and R. SERGE DENISOFF The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributionsand Contradictions' OBSERVERS OF THE SO-CALLED "COUNTER CULTURE" have tended to portray this phenomenonas a new and isolated event. TheodoreRoszak, as well as nu- merousmusic and art historians,have cometo view the "counterculture" as a new reactionto technicalexpertise and the embourgeoismentof growing segmentsof the Americanpeople.2 This position,it would appear,is basicallyindicative of the intellectual"blind men and the elephant"couplet, where a social fact or event is examinedapart from otherstructural phenomena. Instead, it is our contentionthat the "counterculture" or Abbie Hoffman's"Woodstock Nation" is an emergent realityor a productof all that camebefore, sui generis.More simply,the "counter culture"can best be conceptualizedas partof a long historical-intellectualprogres- sion beginningwith the "Gardenof Eden"image of man. -

King Biscuit Time”--Sonny Boy Williamson II and Others (1965) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Edward Komara (Guest Post)*

“King Biscuit Time”--Sonny Boy Williamson II and others (1965) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Edward Komara (guest post)* Sonny Boy Williamson II This King Biscuit show is about flour and the blues, not about flowers and rock music. “King Biscuit Time” was born when the blues harmonica master Sonny Boy Williamson (1899- 1965, born Aleck Miller) visited the newly opened KFFA radio studios in Helena, Arkansas. Seeing radio as a means of promoting his upcoming performances, Williamson pitched the idea of a regular show during the noon hour when his working audiences were taking their lunch breaks. KFFA agreed, securing Max Moore, owner of the Interstate Grocer Company and King Biscuit Flour, as the sponsor. “King Biscuit Time” debuted on November 21, 1941 at 12:15 pm, with Williamson and guitarist Robert Lockwood playing for 15 minutes. The success was immediate, allowing the musicians to maintain their time-slot every weekday. They were so successful that, in 1947, while the company’s flour bag continued to have its crown, the corn meal bag began to feature a likeness of Williamson sitting on an ear of corn. As the show continued through the 1940s, additional musicians were brought in to create a band behind Williamson. Chief among them were guitarists Joe “Willie” Wilkins, Earl Hooker and Houston Stackhouse, pianists Robert “Dudlow” Taylor, Willie Love and Pinetop Perkins, and drummer Peck Curtis. During the early broadcasts, Sam Anderson and Hugh Smith served as announcers. John William “Sonny” Payne filled in once in 1941, but he returned in 1951, staying on as the “King Biscuit Time” host until his death in 2018. -

Copyrighted Material

c01.qxd 3/29/06 11:47 AM Page 1 1 Expecting to Fly The businessmen crowded around They came to hear the golden sound —Neil Young Impossible Dreamers For decades Los Angeles was synonymous with Hollywood—the silver screen and its attendant deities. L.A. meant palm trees and the Pacific Ocean, despotic directors and casting couches, a factory of illusion. L.A. was “the coast,” cut off by hundreds of miles of desert and mountain ranges. In those years Los Angeles wasn’t acknowl- edged as a musicCOPYRIGHTED town, despite producing MATERIAL some of the best jazz and rhythm and blues of the ’40s and ’50s. In 1960 the music business was still centered in New York, whose denizens regarded L.A. as kooky and provincial at best. Between the years 1960 and 1965 a remarkable shift occurred. The sound and image of Southern California began to take over, replacing Manhattan as the hub of American pop music. Producer Phil Spector took the hit-factory ethos of New York’s Brill Building 1 c01.qxd 3/29/06 11:47 AM Page 2 2 HOTEL CALIFORNIA songwriting stable to L.A. and blew up the teen-pop sound to epic proportions. Entranced by Spector, local suburban misfit Brian Wil- son wrote honeyed hymns to beach and car culture that reinvented the Golden State as a teenage paradise. Other L.A. producers followed suit. In 1965, singles recorded in Los Angeles occupied the No. 1 spot for an impressive twenty weeks, compared to just one for New York. On and around Sunset, west of old Hollywood before one reached the manicured pomp of Beverly Hills, clubs and coffee- houses began to proliferate.