EXPLORING PSYCHOLOGICAL STRATEGIES to MANAGE FATIGUE in ENDURANCE SPORT by D. T. ROBINSON Research Project Submitted to Univers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

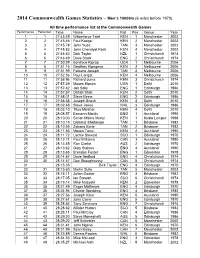

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m (6 miles before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:45.39 Wilberforce Talel KEN 1 Manchester 2002 2 2 27:45.46 Paul Kosgei KEN 2 Manchester 2002 3 3 27:45.78 John Yuda TAN 3 Manchester 2002 4 4 27:45.83 John Cheruiyot Korir KEN 4 Manchester 2002 5 5 27:46.40 Dick Taylor NZL 1 Christchurch 1974 6 6 27:48.49 Dave Black ENG 2 Christchurch 1974 7 7 27:50.99 Boniface Kiprop UGA 1 Melbourne 2006 8 8 27:51.16 Geoffrey Kipngeno KEN 2 Melbourne 2006 9 9 27:51.99 Fabiano Joseph TAN 3 Melbourne 2006 10 10 27:52.36 Paul Langat KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 11 11 27:56.96 Richard Juma KEN 3 Christchurch 1974 12 12 27:57.39 Moses Kipsiro UGA 1 Delhi 2010 13 13 27:57.42 Jon Solly ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 14 14 27:57.57 Daniel Salel KEN 2 Delhi 2010 15 15 27:58.01 Steve Binns ENG 2 Edinburgh 1986 16 16 27:58.58 Joseph Birech KEN 3 Delhi 2010 17 17 28:02.48 Steve Jones WAL 3 Edinburgh 1986 18 18 28:03.10 Titus Mbishei KEN 4 Delhi 2010 19 19 28:08.57 Eamonn Martin ENG 1 Auckland 1990 20 20 28:10.00 Simon Maina Munyi KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 21 21 28:10.15 Gidamis Shahanga TAN 1 Brisbane 1982 22 22 28:10.55 Zakaria Barie TAN 2 Brisbane 1982 23 23 28:11.56 Moses Tanui KEN 2 Auckland 1990 24 24 28:11.72 Lachie Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 25 25 28:12.71 Paul Williams CAN 3 Auckland 1990 25 26 28:13.45 Ron Clarke AUS 2 Edinburgh 1970 27 27 28:13.62 Gary Staines ENG 4 Auckland 1990 28 28 28:13.65 Brendan Foster ENG 1 Edmonton 1978 29 29 28:14.67 -

MEDIA INFO & Fast Facts

MEDIAWELCOME INFO MEDIA INFO Media Info & FAST FacTS Media Schedule of Events .........................................................................................................................................4 Fact Sheet ..................................................................................................................................................................6 Prize Purses ...............................................................................................................................................................8 By the Numbers .........................................................................................................................................................9 Runner Pace Chart ..................................................................................................................................................10 Finishers by Year, Gender ........................................................................................................................................11 Race Day Temperatures ..........................................................................................................................................12 ChevronHoustonMarathon.com 3 MEDIA INFO Media Schedule of Events Race Week Press Headquarters George R. Brown Convention Center (GRB) Hall D, Third Floor 1001 Avenida de las Americas, Downtown Houston, 77010 Phone: 713-853-8407 (during hours of operation only Jan. 11-15) Email: [email protected] Twitter: @HMCPressCenter -

Official Journal of the British Milers' Club

Official Journal of the British Milers’ Club VOLUME 3 ISSUE 14 AUTUMN 2002 The British Milers’ Club Contents . Sponsored by NIKE Founded 1963 Chairmans Notes . 1 NATIONAL COMMITTEE President Lt. CoI. Glen Grant, Optimum Speed Distribution in 800m and Training Implications C/O Army AAA, Aldershot, Hants by Kevin Predergast . 1 Chairman Dr. Norman Poole, 23 Burnside, Hale Barns WA15 0SG An Altitude Adventure in Ethiopia by Matt Smith . 5 Vice Chairman Matthew Fraser Moat, Ripple Court, Ripple CT14 8HX End of “Pereodization” In The Training of High Performance Sport National Secretary Dennis Webster, 9 Bucks Avenue, by Yuri Verhoshansky . 7 Watford WD19 4AP Treasurer Pat Fitzgerald, 47 Station Road, A Coach’s Vision of Olympic Glory by Derek Parker . 10 Cowley UB8 3AB Membership Secretary Rod Lock, 23 Atherley Court, About the Specificity of Endurance Training by Ants Nurmekivi . 11 Upper Shirley SO15 7WG BMC Rankings 2002 . 23 BMC News Editor Les Crouch, Gentle Murmurs, Woodside, Wenvoe CF5 6EU BMC Website Dr. Tim Grose, 17 Old Claygate Lane, Claygate KT10 0ER 2001 REGIONAL SECRETARIES Coaching Frank Horwill, 4 Capstan House, Glengarnock Avenue, E14 3DF North West Mike Harris, 4 Bruntwood Avenue, Heald Green SK8 3RU North East (Under 20s)David Lowes, 2 Egglestone Close, Newton Hall DH1 5XR North East (Over 20s) Phil Hayes, 8 Lytham Close, Shotley Bridge DH8 5XZ Midlands Maurice Millington, 75 Manor Road, Burntwood WS7 8TR Eastern Counties Philip O’Dell, 6 Denton Close, Kempston MK Southern Ray Thompson, 54 Coulsdon Rise, Coulsdon CR3 2SB South West Mike Down, 10 Clifton Down Mansions, 12 Upper Belgrave Road, Bristol BS8 2XJ South West Chris Wooldridge, 37 Chynowen Parc, GRAND PRIX PRIZES (Devon and Cornwall) Cubert TR8 5RD A new prize structure is to be introduced for the 2002 Nike Grand Prix Series, which will increase Scotland Messrs Chris Robison and the amount that athletes can win in the 800m and 1500m races if they run particular target times. -

Cycling Love

f Follow us on Facebook t Follow us on Twitter w Visit goskyride.com LOVECYCLING e Email us Working together to help more people have fun cycling December 2012 2012 highlights including Sky Ride Birmingham and Southampton, Bradley Wiggins winning gold at London 2012, and Big Breeze Bike Ride Hull A wonderful year for cycling at all levels We’d like to say a big thank you for helping us make 2012 the most amazing year for cycling. We couldn’t have done it without your hard work and support. Together we’ve inspired more people to get on their bikes and we hope to continue this inspiration through 2013 and beyond. Our council partners were recently sent copies of our 2012 Local Authority Partner Review. If you’d like to order more copies, or if you’re interested in finding out more about how we work with local authorities, email [email protected] Thank you for your continued support, and best wishes for Christmas and the New Year. Stewart Kellett Director, Recreation & Partnerships, British Cycling More people cycling, more often… Our legacy in action Last week British Cycling celebrated the latest results from Sport England’s Active People survey. The findings show that over 200,000 more people are cycling at least once a week than were in October 2011. This exceeds the target set by Sport England four years ago by over 75,000 and brings the total number of people in England now cycling at least once a week to just under two million. The results also found the number of women cycling more regularly has risen dramatically over the last 12 months to almost 63,000. -

Course Records Course Records

Course records Course records ....................................................................................................................................................................................202 Course record split times .............................................................................................................................................................203 Course record progressions ........................................................................................................................................................204 Margins of victory .............................................................................................................................................................................206 Fastest finishers by place .............................................................................................................................................................208 Closest finishes ..................................................................................................................................................................................209 Fastest cumulative races ..............................................................................................................................................................210 World, national and American records set in Chicago ................................................................................................211 Top 10 American performances in Chicago .....................................................................................................................213 -

Chicago Year-By-Year

YEAR-BY-YEAR CHICAGO MEDCHIIAC INFOAGO & YEFASTAR-BY-Y FACTSEAR TABLE OF CONTENTS YEAR-BY-YEAR HISTORY 2011 Champion and Runner-Up Split Times .................................... 126 2011 Top 25 Overall Finishers ....................................................... 127 2011 Top 10 Masters Finishers ..................................................... 128 2011 Top 5 Wheelchair Finishers ................................................... 129 Chicago Champions (1977-2011) ................................................... 130 Chicago Champions by Country ...................................................... 132 Masters Champions (1977-2011) .................................................. 134 Wheelchair Champions (1984-2011) .............................................. 136 Top 10 Overall Finishers (1977-2011) ............................................. 138 Historic Event Statistics ................................................................. 161 Historic Weather Conditions ........................................................... 162 Year-by-Year Race Summary............................................................ 164 125 2011 CHAMPION/RUNNER-UP SPLIT TIMES 2011 TOP 25 OVERALL FINISHERS 2011 CHAMPION AND RUNNER-UP SPLIT TIMES 2011 TOP 25 OVERALL FINISHERS MEN MEN Moses Mosop (KEN) Wesley Korir (KEN) # Name Age Country Time Distance Time (5K split) Min/Mile/5K Time Sec. Back 1. Moses Mosop ..................26 .........KEN .................................... 2:05:37 5K .................00:14:54 .....................04:47 -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J. -

PDF Download Bradley Wiggins: Tour De Force

BRADLEY WIGGINS: TOUR DE FORCE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Deering | 256 pages | 01 Jan 2013 | Birlinn General | 9781780271033 | English | Edinburgh, United Kingdom Bradley Wiggins: Tour de Force PDF Book BBC Sport. Geraint not on form will probably be where Richie Porte is at the moment, Geraint on form would be challenging to win the race. Update preferences. Retrieved 18 July Archived from the original PDF on 20 September Allez allez allez! Retrieved 5 May It seems that they were all lured to Lancs by the state-of-art Manchester Velodrome and some serious hills to stretch those tendons to capacity. Retrieved 28 July In January it was confirmed that Wiggins had signed a contract extension with Team Sky to the end of April , with a focus on attempting to win Paris —Roubaix , before transferring to his newly founded WIGGINS team in order to prepare alongside other members of the British track endurance squad for the team pursuit at the Summer Olympics. Blog Stats , hits. However Wiggins said that he was happy with his performance, stating "that was the strongest I've been in a team pursuit, so there's a bit of life left in me yet, and I've got another four or five months to get a bit better". Lance Armstrong won the award in , , , and , but his results were removed due to the doping case. In March Wiggins competed in the track world championships in Manchester, defending his individual pursuit title by beating Dutchman Jenning Huizenga in the final, his third world title in the discipline. Time Inc. -

2013 World Championships Statistics - Men’S Marathon by K Ken Nakamura

2013 World Championships Statistics - Men’s Marathon by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Moskva: 1) No nation ever swept the medal in the Worlds. Can ETH or KEN change that? 2) 2007 was the last time African born runner did NOT sweep the medal? Will Africans continue to dominate? All time Performance List at the World Championships Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 2:06:54 Abel Kirui KEN 1 Berlin 2009 2 2:07:38 Abel Kirui 1 Daegu 2011 3 2 2:07:48 Emmanuel Mutai KEN 2 Berlin 2009 4 3 2:08:31 Jaouad Gharib MAR 1 Paris 2003 5 4 2:08:35 Tsegaye Kebede ETH 3 Berlin 2009 6 5 2:08:38 Julio Rey ESP 2 Paris 2003 7 6 2:08:42 Adhane Yemane Tsegay ETH 4 Berlin 2009 8 7 2:09:14 Stefano Baldini ITA 3 Paris 2003 9 8 2:09:25 Alberto Chaiça POR 4 Paris 2003 10 9 2:09:26 Shigeru Aburaya JPN 5 Paris 2003 11 10 2:09:29 Daniele Caimmi ITA 6 Paris 2003 12 11 2:10:03 Rob de Castella AUS 1 Helsinki 1983 13 12 2:10:06 Vincent Kipruto KEN 2 Daegu 2011 14 2:10:10 Jaouad Gharib 1 Helsinki 2005 15 13 2:10:17 Ian Syster RSA 7 Paris 2003 15 14 2:10:21 Christopher Isegwe TAN 2 Helsinki 2005 16 15 2:10:27 Kebede Balcha ETH 2 Helsinki 1983 18 16 2:10:32 Feyisa Lilesa ETH 3 Daegu 2011 19 17 2:10:35 Michael Kosgei Rotich KEN 8 Paris 2003 20 18 2:10:37 Waldemar Cierpinski GDR 3 Helsinki 1983 21 19 2:10:37 Hendrick Ramaala RSA 9 Paris 2003 22 20 2:10:38 Kjell-Erik Ståhl SWE 4 Helsinki 1983 22 21 2:10:38 Atsushi Sato JPN 10 Paris 2003 22 22 2:10:38 Lee Bong-Ju KOR 11 Paris 2003 25 23 2:10:39 Tsuyoshi Ogata JPN 12 Paris 2003 26 24 2:10:42 Agapius -

Dimeo and Henning Final.Pdf

This is an Accepted Manuscript of a chapter published by Taylor & Francis Group in Fincoeur B, Gleaves J & Ohl F (eds.) Doping in Cycling: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Ethics and Sport. Doping in Cycling: Interdisciplinary Perspectives: Routledge, pp. 177-188. https://www.routledge.com/Doping-in-Cycling-Interdisciplinary-Perspectives-1st- Edition/Fincoeur-Gleaves-Ohl/p/book/9781138477902 The Decline of Trust in British Sport since the London Olympics: Team Sky’s Fall from Grace Paul Dimeo and April Henning Abstract The success of Team Sky has been over-shadowed by a range of allegations and controversies, leaving significant doubts around their much-vaunted pro anti-doping stance. This chapter aims to contextualise these doubts within the wider frame of British sport, and more specifically the decline of trust. We trace the emergence of Team Sky from the National Lottery funded track team, arguing that the London Olympics was a pinnacle of medal-winning and public admiration. The turn towards professional road cycling was accompanied by new approaches to medicalisation. The Fancy Bears hack of WADA’s database, whistle-blower insights, Government inquiries, and media scrutiny have presented the public with sufficient evidence and critique to undermine the reputation of Team Sky’s management and riders. Other factors have contributed to the decline of trust, not least evidence of doping from the Russia investigations, the leaked IAAF blood files, the role of the IAAF senior managers, the conflict between WADA and the IOC over banning Russian athletes, and other related debates. We argue that the high-profile debate over the use of drugs in British professional cycling can be understood as symptomatic of a wider malaise affecting British sport, which in turn can be contextualised, explained, and seen as part of a broader shift in scepticism regarding political leaders and media organisations. -

Many University of Liverpool

2012 EDITION SIGHT A child’s hope University research tackles global challenges I Women in engineering I A new driving force in Formula 1 I 120 years of the Victoria Building I From twilight shift to Chief Executive I The generation game IN PROFILE INSIGHT UNIVERSITY OF LIVERPOOL ALUMNI MAGAZINE SIGHT2012 EDITION 2012 EDITION CONTENTS The summer months have been REGULARS an extremely busy 16 University news 02 Honorary graduates 28 time, with alumni City news 10 International news 32 events taking place Then and now 18 Student spotlight 34 across the globe Diary dates 21 In memoriam 37 in locations such Benefits and services 24 In touch 38 as the Cayman Benefactors’ Fund update 26 Events and reunions 42 Islands, London, FEATURES and Switzerland. From twilight shift to Chief Executive 06 It is the increasingly international Alumnus Philip Clarke tells insight how he went from stacking shelves in his local Tesco nature of our work that has, in part, to becoming the retail giant’s Chief Executive. The team in Liverpool, like many people prompted the University to consider around the world, has also been gripped the governance structures for alumni by Olympic and Paralympic fever, not relations currently outlined in its Statues least because we boast four Olympic and and Ordinances, and to openly consult 06 120 years of the Victoria Building 08 Paralympic athletes connected with the with alumni about these (see page 25 Celebrating the 120th anniversary of our flagship Victoria Building which gave rise to University. They include bronze medal- for more details). We want to make the term ‘redbrick university’. -

LE STATISTICHE DELLA MARATONA 1. Migliori Prestazioni Mondiali Maschili Sulla Maratona Tabella 1 2. Migliori Prestazioni Mondial

LE STATISTICHE DELLA MARATONA 1. Migliori prestazioni mondiali maschili sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 1) 2h03’38” Patrick Makau Musyoki KEN Berlino 25.09.2011 2) 2h03’42” Wilson Kipsang Kiprotich KEN Francoforte 30.10.2011 3) 2h03’59” Haile Gebrselassie ETH Berlino 28.09.2008 4) 2h04’15” Geoffrey Mutai KEN Berlino 30.09.2012 5) 2h04’16” Dennis Kimetto KEN Berlino 30.09.2012 6) 2h04’23” Ayele Abshero ETH Dubai 27.01.2012 7) 2h04’27” Duncan Kibet KEN Rotterdam 05.04.2009 7) 2h04’27” James Kwambai KEN Rotterdam 05.04.2009 8) 2h04’40” Emmanuel Mutai KEN Londra 17.04.2011 9) 2h04’44” Wilson Kipsang KEN Londra 22.04.2012 10) 2h04’48” Yemane Adhane ETH Rotterdam 15.04.2012 Tabella 1 2. Migliori prestazioni mondiali femminili sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 1) 2h15’25” Paula Radcliffe GBR Londra 13.04.2003 2) 2h18’20” Liliya Shobukhova RUS Chicago 09.10.2011 3) 2h18’37” Mary Keitany KEN Londra 22.04.2012 4) 2h18’47” Catherine Ndereba KEN Chicago 07.10.2001 1) 2h18’58” Tiki Gelana ETH Rotterdam 15.04.2012 6) 2h19’12” Mizuki Noguchi JAP Berlino 15.09.2005 7) 2h19’19” Irina Mikitenko GER Berlino 28.09.2008 8) 2h19’36’’ Deena Kastor USA Londra 23.04.2006 9) 2h19’39’’ Sun Yingjie CHN Pechino 19.10.2003 10) 2h19’50” Edna Kiplagat KEN Londra 22.04.2012 Tabella 2 3. Evoluzione della migliore prestazione mondiale maschile sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 2h55’18”4 Johnny Hayes USA Londra 24.07.1908 2h52’45”4 Robert Fowler USA Yonkers 01.01.1909 2h46’52”6 James Clark USA New York 12.02.1909 2h46’04”6