Journal of Bengali Studies Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL Millenniumpost.In

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL millenniumpost.in pages millenniumpost NO HALF TRUTHS th28 NEW DELHI & KOLKATA | MAY 2018 Contents “Dharma and Dhamma have come home to the sacred soil of 63 Simplifying Doing Trade this ancient land of faith, wisdom and enlightenment” Narendra Modi's Compelling Narrative 5 Honourable President Ram Nath Kovind gave this inaugural address at the International Conference on Delineating Development: 6 The Bengal Model State and Social Order in Dharma-Dhamma Traditions, on January 11, 2018, at Nalanda University, highlighting India’s historical commitment to ethical development, intellectual enrichment & self-reformation 8 Media: Varying Contours How Central Banks Fail am happy to be here for 10 the inauguration of the International Conference Unmistakable Areas of on State and Social Order 12 Hope & Despair in IDharma-Dhamma Traditions being organised by the Nalanda University in partnership with the Vietnam The Universal Religion Buddhist University, India Foundation, 14 of Swami Vivekananda and the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. In particular, Ethical Healthcare: A I must welcome the international scholars and delegates, from 11 16 Collective Responsibility countries, who have arrived here for this conference. Idea of India I understand this is the fourth 17 International Dharma-Dhamma Conference but the first to be hosted An Indian Summer by Nalanda University and in the state 18 for Indian Art of Bihar. In a sense, the twin traditions of Dharma and Dhamma have come home. They have come home to the PMUY: Enlightening sacred soil of this ancient land of faith, 21 Rural Lives wisdom and enlightenment – this land of Lord Buddha. -

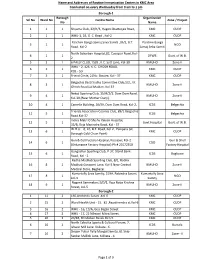

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

2068-07 (Mid Nov ,2011)

BANKING & FINANCIAL STATISTICS Monthly NEPAL RASTRA BANK Bank & Financial Institution Regulation Department Statistics Division 1000 911 923 879 900 872 865 800 730 713 709 714 727 700 600 500 400 300 Rs. in Rs. billion 200 100 0 Mid Jul Mid Aug Mid Sep Mid Oct Mid Nov Deposit d 2068 Kartik (Mid Nov, 2011) (Provisional) Contents Page 1. Explanatory note 1 2. Major financial indicators 2 (Statement of Assets and Liabilities of Bank & Financial Institutions (Aggregate) 3. Geographical distribution of: (not complete) a. Bank & financial institutions' branches b. Deposit c. Credit 4. Statement of Assets and Liabilities a. Commercial banks 11 b. Development banks 14 c. Finance companies 22 d. Micro‐credit development banks 29 5. Profit & Loss account a. Commercial banks 31 b. Development banks 35 c. Finance companies 46 d. Micro‐credit development banks 56 6. Sector‐ wise, product‐wise and security‐wise credit a. Commercial banks 59 b. Development banks 62 c. Finance companies 71 d. Micro‐credit development banks 79 7. Some financial ratios (not complete) 8. Progress report of micro‐credit development banks (not com.) 9. List of bank and financial institutions with short name 81 Explanatory Notes 1 "Banking and Financial Statistics, Monthly" contains statistical information of NRB licensed Banks and Financial Institutions (BFIs). 2 Blank spaces in the headings and sub‐headings indicate the unavailability of data or nil in transactions or not submitted in prescribed format. 3 The following months of the Gregorian Calendar year are the approximate equivalent of the months of the Nepalese Calendar Year: Gregorian Month Nepalese Month Mid‐Apr/Mid‐May Baisakh Mid‐May/Mid‐June Jestha Mid‐June/Mid‐July Ashadh Mid‐July/Mid‐Aug Shrawan Mid‐Aug /Mid‐Sept Bhadra Mid‐Sept/Mid‐Oct Aswin Mid‐Oct/Mid‐Nov Kartik Mid‐Nov/Mid‐Dec Marga Mid‐Dec/Mid‐Jan Poush Mid‐Jan/Mid‐Feb Magh Mid‐Feb/Mid‐Mar Falgun Mid‐Mar/Mid‐Apr Chaitra 4 Statistics of following Licensed BFIs have been used. -

Between Violence and Democracy: Bengali Theatre 1965–75

BETWEEN VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRACY / Sudeshna Banerjee / 1 BETWEEN VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRACY: BENGALI THEATRE 1965–75 SUDESHNA BANERJEE 1 The roots of representation of violence in Bengali theatre can be traced back to the tortuous strands of socio-political events that took place during the 1940s, virtually the last phase of British rule in India. While negotiations between the British, the Congress and the Muslim League were pushing the country towards a painful freedom, accompanied by widespread communal violence and an equally tragic Partition, with Bengal and Punjab bearing, perhaps, the worst brunt of it all; the INA release movement, the RIN Mutiny in 1945-46, numerous strikes, and armed peasant uprisings—Tebhaga in Bengal, Punnapra-Vayalar in Travancore and Telengana revolt in Hyderabad—had underscored the potency of popular movements. The Left-oriented, educated middle class including a large body of students, poets, writers, painters, playwrights and actors in Bengal became actively involved in popular movements, upholding the cause of and fighting for the marginalized and the downtrodden. The strong Left consciousness, though hardly reflected in electoral politics, emerged as a weapon to counter State violence and repression unleashed against the Left. A glance at a chronology of events from October 1947 to 1950 reflects a series of violent repressive measures including indiscriminate firing (even within the prisons) that Left movements faced all over the state. The history of post–1964 West Bengal is ridden by contradictions in the manifestation of the Left in representative politics. The complications and contradictions that came to dominate politics in West Bengal through the 1960s and ’70s came to a restive lull with the Left Front coming to power in 1977. -

The Mughal Empire – Baburnama “The Untouchables” Powerpoint Notes Sections 27-28: * Babur Founded the Mughal Empire, Also Called the Timurid State

HUMA 2440 term 1 exam review Week 1 Section 1: India – An Overview * „Local‟ name: Bharat * Gained independence in 1947 * Capital is New Delhi * Official languages Hindi and English Section 2: Chronology and Maps * Gangetic Valley 1000-500 BC Maurya Empire under Ashoka 268-233 BC India 0-300 AD Gupta Empire 320-500 Early Middle Ages 900-1200 Late Middle Ages 1206-1526 Mughal Empire British Penetration of India 1750-1860 Republic of India 1947 Powerpoint notes Varna – caste (colour). Primarily Hindu societal concept Class /= caste. Is a set of social relations within a system of production (financial). Caste, conversely, is something you‟re born into. * as caste barriers are breaking down in modern India, class barriers are becoming more prominent. * first mention of caste differences are in the Rig Veda, which may have referred to main divisions of ancient Aryan society * the Rig Veda mentions a creation myth “Hymn of the Primeval Man” which refers to the creation of the universe and the division of man into four groups of body parts (below under section 3) * outsiders consider caste to the be the defining aspect of indian society. Megasthenes and Alberuni both focus on that when they analyze the culture. Jati or jat – subcaste. these have distinct names like “Gaud Saraswat Brahmins”. Dalit – untouchable Dvija – twice-born: part-way through a non-sudra person‟s life, they go through a „spiritual birth‟ which is their „second birth‟, called the upanayana, where the initiated then wear a sacred thread Hierarchy – different types of ordered ranks systems. i.e. gender hierarchy is male > female, sexual hierarchy is heterosexual > homosexual * rank can be inherited at birth (from father) * one‟s birth/rebirth is based on one‟s deeds in a past life Endogamy – marriage within own caste Commensality – can only eat with jati members Jatidharma and varna-dharma – one‟s duty in a caste or subcaste (lower castes must serve higher castes) Jajmani system – patron-client system of land owning and service/artisan castes. -

Nationalism in India Lesson

DC-1 SEM-2 Paper: Nationalism in India Lesson: Beginning of constitutionalism in India Lesson Developer: Anushka Singh Research scholar, Political Science, University of Delhi 1 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Content: Introducing the chapter What is the idea of constitutionalism A brief history of the idea in the West and its introduction in the colony The early nationalists and Indian Councils Act of 1861 and 1892 More promises and fewer deliveries: Government of India Acts, 1909 and 1919 Post 1919 developments and India’s first attempt at constitution writing Government of India Act 1935 and the building blocks to a future constitution The road leading to the transfer of power The theory of constitutionalism at work Conclusion 2 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Introduction: The idea of constitutionalism is part of the basic idea of liberalism based on the notion of individual’s right to liberty. Along with other liberal notions,constitutionalism also travelled to India through British colonialism. However, on the one hand, the ideology of liberalism guaranteed the liberal rightsbut one the other hand it denied the same basic right to the colony. The justification to why an advanced liberal nation like England must colonize the ‘not yet’ liberal nation like India was also found within the ideology of liberalism itself. The rationale was that British colonialism in India was like a ‘civilization mission’ to train the colony how to tread the path of liberty.1 However, soon the English educated Indian intellectual class realised the gap between the claim that British Rule made and the oppressive and exploitative reality of colonialism.Consequently,there started the movement towards autonomy and self-governance by Indians. -

INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 1885-1947 Year Place President

INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 1885-1947 Year Place President 1885 Bombay W.C. Bannerji 1886 Calcutta Dadabhai Naoroji 1887 Madras Syed Badruddin Tyabji 1888 Allahabad George Yule First English president 1889 Bombay Sir William 1890 Calcutta Sir Pherozeshah Mehta 1891 Nagupur P. Anandacharlu 1892 Allahabad W C Bannerji 1893 Lahore Dadabhai Naoroji 1894 Madras Alfred Webb 1895 Poona Surendranath Banerji 1896 Calcutta M Rahimtullah Sayani 1897 Amraoti C Sankaran Nair 1898 Madras Anandamohan Bose 1899 Lucknow Romesh Chandra Dutt 1900 Lahore N G Chandravarkar 1901 Calcutta E Dinsha Wacha 1902 Ahmedabad Surendranath Banerji 1903 Madras Lalmohan Ghosh 1904 Bombay Sir Henry Cotton 1905 Banaras G K Gokhale 1906 Calcutta Dadabhai Naoroji 1907 Surat Rashbehari Ghosh 1908 Madras Rashbehari Ghosh 1909 Lahore Madanmohan Malaviya 1910 Allahabad Sir William Wedderburn 1911 Calcutta Bishan Narayan Dhar 1912 Patna R N Mudhalkar 1913 Karachi Syed Mahomed Bahadur 1914 Madras Bhupendranath Bose 1915 Bombay Sir S P Sinha 1916 Lucknow A C Majumdar 1917 Calcutta Mrs. Annie Besant 1918 Bombay Syed Hassan Imam 1918 Delhi Madanmohan Malaviya 1919 Amritsar Motilal Nehru www.bankersadda.com | www.sscadda.com| www.careerpower.in | www.careeradda.co.inPage 1 1920 Calcutta Lala Lajpat Rai 1920 Nagpur C Vijaya Raghavachariyar 1921 Ahmedabad Hakim Ajmal Khan 1922 Gaya C R Das 1923 Delhi Abul Kalam Azad 1923 Coconada Maulana Muhammad Ali 1924 Belgaon Mahatma Gandhi 1925 Cawnpore Mrs.Sarojini Naidu 1926 Guwahati Srinivas Ayanagar 1927 Madras M A Ansari 1928 Calcutta Motilal Nehru 1929 Lahore Jawaharlal Nehru 1930 No session J L Nehru continued 1931 Karachi Vallabhbhai Patel 1932 Delhi R D Amritlal 1933 Calcutta Mrs. -

EMPLOYEE DUES AS on 17.10.2017 Attention

Date: 18.12.2017 EMPLOYEE DUES AS ON 17.10.2017 Attention: 1. The classification of employees as “workmen” [as defined in sec. 2(a) of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code read with sec. 2(s) of Industrial Disputes Act, 1947] of Nicco Corporation Limited (“Company”) has been done by competent retained officials the Company. 2. This document has been divided into two parts: a. Claims received from workmen (Annexure- A); and b. Claims admitted as per books of the Company (Annexure- B). 3. Amount claimed by workers/workers’ representatives in respect of NRETF contributions cannot be admitted as a claim, as the said amount, deducted from wages/salaries has been appropriated towards issue of equity shares of the Company. 4. In case the below mentioned amounts is not agreeable to any workman/workmen’s representative, the concerned person may contact Mr D P Thakur (email id- [email protected]) or Mr. Subhroto Bhattacharjee (email [email protected]) handling the said computation. In case there still remains any discrepancy, the same may be reported to the Liquidator by email to [email protected]. The Liquidator shall review the supporting documents/ information provided and consider the same for removal of any such discrepancy. 5. The Liquidator may upload a corrected /amended list on claims ANNEXURE- A: CLAIMS RECEIVED FROM EMPLOYEES Soft Gas & Furnishing CLAIM Coveyance Superannuation Medical Leave Oldage Futer Service Total Name of Party and address Salary Elctricity Bonus Gratuity Exp./ Club/ LTA Interest NO. allowance Due reimbursement Encashment Benefit Compensation Claim allowance Home Entertainment Bikash Manik Beneras Road, E1 232800 3000 7200 30150 13600 30150 150596 708358 PO-Chamrail, Dist. -

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Remembered Villages • 319

Remembered Villages • 319 gender though one would suspect, from the style of writing, that with the exception of one, the essays were written by men. The authors recount their memories of their native villages—sixty-seven in all—of East Bengal belonging to some eighteen districts. Written in the aftermath of parti- tion, these essays capture the sense of tragedy that the division of the country represented to these authors. This attitude was more Hindu 16 than Muslim, for to many if not most of the Muslims of East Pakistan, 1947 was not only about partition, it was also about freedom, from both the British and the Hindu ruling classes.4 Remembered Villages My aim is to understand the structure of sentiments expressed in these essays. One should remember the context. There is no getting Representations of Hindu-Bengali Memories around the fact that partition was traumatic for those who had to leave in the Aftermath of the Partition their homes. Stories and incidents of sexual harassment and degradation of women, of forced eviction, of physical violence and humiliation marked their experience. The Hindu Bengali refugees who wrote these essays DIPESH CHAKRABARTY had to make a new life in the difficult circumstances of the overcrowded city of Calcutta. Much of the story of their attempts to settle down in the different suburbs of Calcutta is about squatting on government or privately owned land and about reactive violence by the police and landlords.5 emory is a complex phenomenon that reaches out to far beyond The sudden influx of thousands of people into a city where the services what normally constitutes an historian's archives, for memory were already stretched to their limits, could not have been a welcome is much more than what the mind can remember or what event. -

Calendar 2020 #Spiritualsocialnetwork Contact Us @Rgyanindia FEBRUARY 2020 Magha - Phalguna 2076

JANUARY 2020 Pausa - Magha 2076 Subh Muhurat Sukla Paksha Dashami Krishna Paksha Dwitiya Krishna Paksha Dashami Republic Day Festivals, Vrats & Holidays Marriage: 15,16, 17, Pausha Magha Magha 1 English New Year ५ १२ १९ २६ 26 Sun 18, 20, 29, 30, 31 5 25 12 2 19 10 2 Guru Gobind Singh Jayanti Ashwini Pushya Vishakha Dhanishtha Nature Day रव. Griha Pravesh: 29, 30 Mesha Dhanu Karka Dhanu Tula Makara Makara Makara 3 Masik Durgashtami, Banada Vehicle Purchase: 3, Pausa Putrada Ekadashi Krishna Paksha Tritiya Shattila Ekadashi Sukla Paksha Tritiya Ashtami 8, 10, 17, 20, 27, 30, Pausha Magha Magha Magha 6 Vaikuntha Ekadashi, Paush 31 ६ १३ २० २७ MON 6 26 13 3 20 11 27 18 Putrada Ekadashi, Tailang Bharani Ashlesha Anuradha Shatabhisha Swami Jayanti सोम. Property Purchase: 10, 30, 31 Mesha Dhanu Karka Dhanu Vrishabha Makara Kumbha Makara 7 Kurma Dwadashi Namakaran: 2, 3, 5, Sukla Paksha Dwadashi K Chaturthi LOHRI Krishna Paksha Dwadashi Sukla Paksha Tritiya 8 Pradosh Vrat, Rohini Vrat 8, 12, 15, 16, 17, 19, Pausha Magha Magha Magha 10 Paush Purnima, Shakambhari 20, 27, 29, 30, 31 ७ १४ २१ २८ TUE 7 27 14 4 21 12 28 18 Purnima, Magh Snan Start Krittika Magha Jyeshtha Shatabhisha 12 National Youth Day, Swami मंगल. Mundan: 27, 31 Vrishabha Dhanu Simha Dhanu Vrishabha Makara Kumbha Makara Vivekananda Jayanti English New Year Sukla Paksha Trayodashi Makar Sankranti, Pongal Krishna Paksha Trayodashi Vasant Panchami 13 Sakat Chauth, Lambodara Pausha Magha Sankashti Chaturthi १ ८ १५ २२ २९ WED 1 21 8 28 15 5 22 13 29 14 Lohri Purva Bhadrapada Rohini Uttara Phalguni Mula Purva Bhadrapada 15 Makar Sankranti, Pongal बुध.