Comparison of Ferry Boat and Highway Bridge Energy Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semi-Monthly Report

SEMI-MONTHLY REPORT “A friendly community in which to live, work and play” February 22, 2013 Upcoming City Council Meetings… March 7, 2013 – City Council Meeting @ 7:00pm – City Council Chambers March 21, 2013 – City Council Meeting @ 7:00pm – City Council Chambers March 27, 2013 – Special Council Meeting @ 12 Noon – City Council Chambers April 4, 2013 – City Council Meeting @ 7:00pm – City Council Chambers . City Administration… The City is now contracting with Procomm Inc. for our information technology (I.T.) services. Chris Cannon will remain our contact and he will continue to provide weekly site visits on Wednesday’s. The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) will temporarily suspend service of the Real McCoy II Ferry for approximately two-weeks starting on Monday, February 25th until Sunday, March 10th to perform preventive maintenance, and make repairs to the ferry slip. The Real McCoy II is scheduled to be closed Monday, February 25th at 12:01 a.m. until 12:01 a.m. on Sunday, March 10th. All work is weather permitting. During the service interruption, motorists are advised to use Highway 160 and the J-Mack Ferry along Highway 220. For the latest information, motorists can call the Caltrans Ryer Island Ferry Update Line at (510) 622-0120. City Council Reports… Report by Vice Mayor Constance Boulware: I met with Yolo-Solano QMD Air Monitoring Technician Mike Breuning and Executive Director Mat Ehrhardt at the Rio Vista air quality monitoring station. Rio Vista has healthy air most of the year. But there are days in which air pollution can cause health problems for children, the elderly or those with lung or heart ailments. -

Appendix C – Train Car Model

APPENDIX C Train Car Model: Public Outreach BART Fleet of the Future Train Car Model Survey Thank you for visiting BART’s train car model today. Please complete this brief survey to let us know what you think. BART appreciates your input. TRAIN CAR MODEL 1. Based on what you’ve seen today, how would you rate the new train car design? Excellent Good Only Fair Poor 2. Please tell us why you rated the train car design this way. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ 3. Do you have any other comments or suggestions about the train car design? ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Ferry Privatization Study

August 2012 Public Private Partnership Opportunities Study Prepared for: Regional Planning Commission RPC Project Number: LA-FB-OPS2 FTA Grant Number: LA 90X377 Jefferson-Orleans-St. Bernard Parishes, LA Crescent City Connection Ferry Public Private Partnership Opportunities Study RPC Project Number: LA-FB-OPS2 FTA Grant Number LA 90X337 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 I. Purpose of Study ............................................................................................................................... 5 II. Project Area ...................................................................................................................................... 5 III. Planning Assumptions ....................................................................................................................... 6 Existing Conditions ........................................................................................................................................ 8 I. Equipment ......................................................................................................................................... 8 II. Facilities............................................................................................................................................ -

I-80 East Comprehensive Multimodal Corridor Plan

I-80 East Comprehensive Multimodal Corridor Plan Caltrans District 4 June 2020 I -8 0 E a s t C omp r e h e n s i v e Mu l t i mo d a l C o r r i d o r P l a n APPROVED BY: I accept this Comprehensive Multimodal Corridor Plan for the I-80 East Corridor as a document informing the regional transportation planning process. ACCEPTED BY: I -8 0 E a s t C omp r e h e n s i v e Mu l t i mo d a l C o r r i d o r P l a n Approval Recommended by: Acknowledgments: Caltrans John McKenzie, Associate Transportation Planner Kyle Pratt, Transportation Planner Brian Johnson, Associate Transportation Planner Solano Transportation Authority Janet Adams, Deputy Executive Director/Director of Projects Robert Guerrero, Director of Planning Brent Rosenwald, Assistant Planner Metropolitan Transportation Commission Lisa Klein, Director, Field Operations and Asset Management Therese Trivedi, Assistant Planning Director Adam Noelting, Principal Planner/Analyst Cover photo by Bill Hall, Caltrans District 4 Photography Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ i Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Caltrans Policy Development .............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Senate Bill 1 and the Solutions for Congested Corridors Program .................................................... -

Arch Thesis Inventory.Xlsx

Page 1 ARCHITECTURE SCHOOL THESES YEAR AUTHOR TITLE 2012 Aditi, Padhi Urban Centre for Justice Re-Investment: Rehabilitation in Treme-Seventh Ward, New Orleans 2012 Asher, Mira Post-Postal: Making Physical Public Space in a Digital World 2012 Bardwell, Kristy Evidence-Bases Design: A New Recovery and Rehabilitation Facility Typology 2012 Berman, Leland Bailey Stitching Houston: Degradation and Creation of Place in the Contemporary Muli-Nodal City 2012 Brooks, Nicholas The Motor City: Networking Density Amongst Decay: Detroit, MI 2012 Cho, Hee Kyung Rebuilding Traditions: A new cemetary for Seoul, South Korea 2012 Coles, Samuel Valu(able)Access(able) Architecture 2012 Dardant. Marie Sophie independence through Integration: Encouraging Variation within a Regulated Environment Manufactured Innovation: A study of community revitalization through systemic manufacturing and creative 2012 Davis, Elizabeth incubation 2012 David. Alexandra Building as threshold: Houston Transitional Center: An architectural nexus 2012 DeCotiis, Matt Planning for Death: A celebration of life through the redesign of the cities of the dead 2012 Diiorio, Laura Take me to the river!: facilitating access to the Mississippi in New Orleans 2012 Faircloth, Gillian Performance of the Collective Memory: Rejuvinating a Culture Through Adaptive Reuse 2012 Finkelstein, Rachel Amplifying Awareness: Atlantic City Re-treat 2012 Fisher, Sean Individual Experience & Collective Memory: The Sports Stadium in Place Making Page 2 2012 Franke, Patrick Flux Capacity: asymmetrical activity -

Item 7.B Att a CTP-Transit Element State of the System

Chapter 3 To chart a successful course for Solano County’s intercity transit and rideshare system, two things are needed: to know where the system is at this time, and to know where STA, partner agencies, and Solano’s transit operators want to be by 2040. Before building the future transit system, it is best to understand the foundation that exists, its strengths and weaknesses, resources needed at its current level of service, and existing opportunities and challenges. This report summarizes the current condition and operation of Solano’s intercity transit and rideshare system as of the end of December 2014. Section 1: The Transit and Rideshare System Defined Overview The Transit and Rideshare System (also simply referred to as ‘The Transit System’) for this report incorporates the modes of intercity bus, passenger rail and passenger ferry service, ridesharing (carpools and vanpools), as well as intercity Paratransit services and Mobility Management. The Transit System consists of the vehicles and supporting infra- structure for those modes of travel. For ridesharing and mobility management, it also includes the staff that supports the programs enabling carpool and vanpool creation and operation, and the delivery of mobility management programs. Solano County has an established and diverse Transit and Rideshare System serving a countywide population of 424,0001. Over 175,000 Solano residents work outside their home. The Transit System serves all trip purposes and a significant portion of commute trips. Between 2009 and 2013, 18% 2of working Solano residents travelled to work by ridesharing, bus, train, or ferry. Transit services connect Solano to the adjacent Sacramento and Bay Area regions via limited-stop buses on highways (I-80, I-680, Highways 12 and 29). -

Delta Voice Fall 2020

DELTA VOICE A publication of the Delta Protection Commission Fall 2020 CONTENTS Pages 1-2 Flood Readiness Page 3 Flood Ready Windsurfing Preparing your property Pages 4-5 Ferries Pages 6-7 Oral Histories Although flooding on leveed Delta islands are a rare occurrence, flood risk Page 8 is a fact of life in the Delta. Floods can happen with little or no warning. A Delta Agency Meetings & powerful rainstorm, rising river, or catastrophic levee failure can happen Delta Flood Prep Week quickly. Property owners must not overlook flood preparations for their homes, other buildings, and businesses. Taking the time to protect your property before a flood will save you money and it may save lives. Before the Flood There is no shortage of items to consider when preparing your property for a potential flood. Begin with waterproofing any subareas, including basements and possible entryways such as window wells. Waterproofing Delta Protection Commission includes making sure rain gutters and storm drains are clear and the slope 2101 Stone Blvd., Suite 240 surrounding your home and other buildings directs water away. Make sure West Sacramento, CA 95691 sump pumps are in working order and tested on a regular basis. delta.ca.gov Continued on page 2... a publication of the Delta Protection Commission Fall 2020 - Page 2 Storm surge can cause a backup of sewage lines and force utilities are restored. If you are able, raise movable that sewage into residences and businesses. Speak to a appliances as high as possible to protect them from licensed plumber to see what options are available to rising water. -

New Links Concept Sketches

New Links Comprehensive Operations Analysis System Report September 2020 Contents Introduction and Project Overview . 1 .5 What is New Links? . 1 .6 What is the purpose of this report? . 1 .6 Why are we doing a bus redesign? . 1 .7 Key Trends, 2012-2019 . 1 .10 What key questions need answering? . 1 .13 Recent crises have introduced new challenges for service planning . 1 .15 System Updates . 1 .15 Key Concepts and Choices . 1 .17 Key transit planning concepts . 1 .18 Access . 1 .20 Frequency . 1 .24 Span . 1 .28 Speed . 1 .28 Better service for the same budget: . 1 .29 System Analysis . 1 .33 Overview . 1 .34 Transit and the built environment . 1 .34 The Network . 1 .37 Downtown Service . 1 .39 Downtown Service - March 2020 Updates . 1 .41 Service Frequency and Span . 1 .42 Peak vs . base service levels . 1 .44 Productivity by Time of Day . 1 .46 Frequency and Productivity . 1 .47 Ridership by Stop . 1 .49 Structure of the network . 1 .50 Direct and indirect routes . 1 .54 Duplicating Service . 1 .56 Exceptions and Outliers . 1 .58 Stop Spacing . 1 .60 Analysis and Service Strategies . 1 .63 System performance . 1 .64 Design and scheduling . 1 .65 Fares and Transfers . 1 .66 Infrastructure . 1 .66 Planning and operations issues . 1 .67 1.3 Figures Figure 1 - Annual ridership for RTA, JET and SBURT services . 1 .6 Figure 2 - Changes to RTA Service and Weekday Hours, 2012-2019 . 1 .9 Figure 3 - % Change in Service Levels for RTA and JET lines, 2012-2018 . 1 .10 Figure 4 - % Change in Annual Ridership, 2012-2018 . -

Crescent City Connection Operations Devolution Or Evolution

1 Crescent City Connection Operations Devolution or Evolution Presentation February 18, 2013 Contents 1. Recent Legislation 2. CCCD Restructuring 3. Toll Funded Services 4. Toll Operations 5. Estimated Annual Revenue and Costs 6. Future Plans 2 ACT No. 866 • Effective January 1, 2013 • Abolishes Mississippi River Bridge Authority MRBA • Terminates Crescent City Connection Division CCCD DOTD 3 ACT No. 866 • Transfers From CCCD To DOTD – Books, records, paper – Funds (previously appropriated) – Property (movable and immovable) – Buildings and Improvements • Abolishes Crescent Connection City Oversight Authority CCCOA 4 ACT No. 866 • Creates Crescent City Transition Fund – Toll Fund Balance as of December 31, 2012 – First $4M for CCCD Ferry Capitalization – Balance to NORPC for lighting, landscaping, grass cutting, trash pickup, improvements to ingress/egress 5 ACT No. 866 • DOTD may take over, control, operate, and regulate the Crescent Connection City Ferries • DOTD may privatize, franchise, or enter into a contract for ferry services – Alone or jointly with parishes or municipalities – Appoints NORPC as an advisor to ferry service contractor 6 ACT No. 865 • Effective January 1, 2013 • Creates a Special Fund, Crescent City Connection (CCC) Toll Fund – Source is Tolls, Administrative Fees, and Late Charges Collected – Not less than $10 M Annually into CCC Capital Projects (CP) Fund – Not to Exceed $2 M Annually to DPS for Police Functions 7 ACT No. 865 • Creates a Special Fund, Crescent City Connection (CCC) Toll Fund (Continued) – Operations and Maintenance Costs – Unexpended Monies transfer to CP Fund – All Monies in the Fund are Subject to Annual Appropriations by the Legislature 8 ACT No. 865 • CP Fund for Projects – “Pay-As-You-Go”, Match for Federal Funds, or Bond Payments – All Monies in the Fund are Subject to Annual Appropriations by the Legislature 9 ACT No. -

State of Tennessee Department of Transportation Commissioner's Office Suite 700, James K

STATE OF TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION COMMISSIONER'S OFFICE SUITE 700, JAMES K. POLK BUILDING 505 DEADERICK STREET NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE 37243-1402 JOHN C. SCHROER (615) 741-2848 BILL HASLAM COMMISSIONER GOVERNOR December 22, 2016 Fiscal Review Committee 8th Floor, Rachel Jackson Bldg. 320 Sixth Avenue North Nashville, TN 37243 RE: River Marine Services, Inc. Contract to operate the Benton-Houston Ferry across the Tennessee River Committee Members, The referenced contract provides for the operation and maintenance for the Benton-Houston ferry across the Tennessee River for the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TOOT). The Contractor has operated this ferry since 1988 at which time the contract was advertised for bid but River Marine Services, Inc. was the only company that submitted a bid for these services. The contract has been renewed every five (5) years since 1988 as a Sole Source Contract. This package contains the following materials as required by your office: 1. Supplemental Documentation Required for Fiscal Review Committee form . 2. A copy of the approved Special Contract Request approving the Sole Source Procurement Method with documentation attached showing TOOT's attempt to locate another possible contractor. 3. A copy of the proposed Summary Sheet. 4. A copy of the proposed Contract to be signed by River Marine Services, Inc. and the Department of Transportation. Please advise if you have any questions or comments. Sincerely, Commissioner -- Supplemental Documentation Required for Fiscal Review Committee Alan -

Esplanade Mall Santa Barbara County Courthouse Goleta Hollister

Transit Services of California and Nevada with connecting services in neighboring states Drain Reedsport LL-Fri LL-Fri LL-Mon Elkton Yoncalla Wells Creek Oakland Sutherlin Key LL-Fri B For detailed information on design choices and what services are or aren't included, see Lakeside Wilbur transitingla.wordpress.com/2018/03/06/california-transit-map North Bend Pony Village Mall Glide Idleyld Park Umpqua Community College LL-Thu This map is intended for reference purposes only. Please verify routes, schedules, and policies with carriers before travel! Map is not to scale. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. This is an unofficial map which is not authorized by or affiliated with any public transportation provider. © 2018-2020 Transiting LA O Version 1.3.7, March 8, 2020 Hauser 1 2 3 For buses and ferries, color coding groups routes of same carrier 99 IC-L/H Stop served by lines 1, 2, and 3 Roseburg Stop served by lines 1 and 3 UTrans Green www.umpquatransit.com Gy Stop served by line 2 Coos County Area Transit (CCAT) Winston www.coostransit.org LL-Tue Dotted line: Limited/seasonal service on line 2 North Bend Newmark Center Dillard Coos Bay Tioga Hotel Thin black dotted line: Pedestrian connection Myrtle Creek Coos Bay 2nd/Central Tenmile Riddle 4 SCBEC Camas Valley Porter Creek Canyonville Dashed line: flex-route/on-demand service on line 4. Box encloses service area with multiple connection points to other lines. LL-Wed IC-MP/C CE Azalea Coquille Quail Trail Public Transit Glendale klamathtribes.org/ administration/bus-schedules -

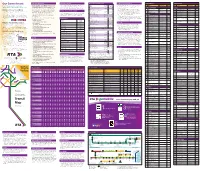

New Orleans RTA System

Our Commitment In and Around New Orleans Passenger Information Fares and Passes/Tarifas y pases Reduced Fare Card ID Program Points of Interest Points of Interest Planning your trip is simple with the Regional Transit RTA is committed to getting you from uptown to downtown and Fares Standard Reduced RTA Buses and Streetcars offer reserved seating and reduced No. Location Served by Line Grid Ref No. Location Served by Line Grid Ref Delivering safe, efficient, courteous, Tarifas Normal Reducida dependable and reliable public transportation Authority(RTA) trip planner found at www.norta.com. all around town. That’s why timetables are available on all of our fares for Seniors 65 and older, People with Disabilities, and vehicles, at pass outlets, public libraries and at www.norta.com. Local Bus and Streetcar Lines Medicare Card Holders. Regional Transit Authority Hospitals When you are ready to go, arrive at your stop 5 minutes before $1.25 $0.40 Servicio local RTA RTA Adminstrative Office 94, 47, 48 F-3 H1 Ochsner Baptist Hospital 15, 16, 24 G-2 RTA New Orleans Social Media your bus or streetcar is scheduled to arrive. Have your fare ready People with Disabilities and Medicare Card Holders require an Express Bus to and from New Orleans Connect with us on all social media platforms to find out the latest when you board and consider purchasing one of our convenient Holidays - Reduced Service Schedule RTA Reduced Fare Card to receive the reduced fare. Call RTA at H2 University Medical Center 39, 84, 47, 48 F-3 East (Lines 62, 63, 64 and 65) $1.50 $0.40 RTA RTA ID Center 94, 47, 48 F-3 504-827-8345 to apply or apply at RTA’s Offices (2817 Canal (Reduced Fare ID cards) news, Rider Alerts and system status updates.