Street Performance Policy in Hong Kong (Interim Report)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Buildings with Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19

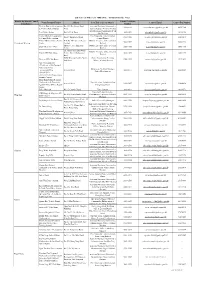

List of Buildings With Confirmed / Probable Cases of COVID-19 List of Residential Buildings in Which Confirmed / Probable Cases Have Resided (Note: The buildings will remain on the list for 14 days since the reported date.) Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5482 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5483 Yau Tsim Mong Block 2, The Long Beach 5484 Kwun Tong Dorsett Kwun Tong, Hong Kong 5486 Wan Chai Victoria Heights, 43A Stubbs Road 5487 Islands Tower 3, The Visionary 5488 Sha Tin Yue Chak House, Yue Tin Court 5492 Islands Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 5496 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5497 Tuen Mun King On House, Shan King Estate 5498 Kowloon City Sik Man House, Ho Man Tin Estate 5499 Wan Chai 168 Tung Lo Wan Road 5500 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5501 Sai Kung Clear Water Bay Apartments 5502 Southern Red Hill Park 5503 Sai Kung Po Lam Estate, Po Tai House 5504 Sha Tin Block F, Garden Rivera 5505 Islands Ying Yat House, Yat Tung Estate 5506 Kwun Tong Block 17, Laguna City 5507 Crowne Plaza Hong Kong Kowloon East Sai Kung 5509 Hotel Eastern Tower 2, Pacific Palisades 5510 Kowloon City Billion Court 5511 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5512 Central & Western Tai Fat Building 5513 Wan Chai Malibu Garden 5514 Sai Kung Alto Residences 5515 Wan Chai Chee On Building 5516 Sai Kung Block 2, Hillview Court 5517 Tsuen Wan Hoi Pa San Tsuen 5518 Central & Western Flourish Court 5520 1 Related Confirmed / District Building Name Probable Case(s) Wong Tai Sin Fu Tung House, Tung Tau Estate 5521 Yau Tsim Mong Tai Chuen Building, Cosmopolitan Estates 5523 Yau Tsim Mong Yan Hong Building 5524 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5525 Sha Tin Yiu Ping House, Yiu On Estate 5526 Sha Tin Block 5, Royal Ascot 5529 Wan Chai Block E, Beverly Hill 5530 Yau Tsim Mong Tower 1, The Harbourside 5531 Yuen Long Wah Choi House, Tin Wah Estate 5532 Yau Tsim Mong Lee Man Building 5533 Yau Tsim Mong Paradise Square 5534 Kowloon City Tower 3, K. -

Address Telephone G/F, 500 Lockhart Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2833

Address Telephone G/F, 500 Lockhart Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2833 1918 Shop 1 & 2, G/F, Sentact Building, 345 King's Road, North Point, HK 2566 3262 Shop 1, G/F, Regent Centre, 88 Queen’s Road Central, HK 2521 2928 G/F & 1/F, 6 D'Aguilar Street, Central, HK 2530 3933 G/F & 1/F, 72&74 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, HK 2895 6112 Shop F35 - F38, 1/F, Kornhill Plaza, 1-2 Kornhill Road, Quarry Bay, HK 2513 1733 Shop G08 & G10, G/F, Port Centre, 38 Chengtu Road, Aberdeen, HK 2580 8811 Shop 312-315, 3/F, New Jade Shopping Arcade, 233 Chai Wan Road, Chai Wan, HK 2976 5620 Shop 3A & B, G/F & 1/F, AT Tower, 180 Electric Road, Fortress Hill, HK 2578 1002 Shop 32-34, 1/F, The Peak Galleria, 118 Peak Road, HK 2849 2868 G/F & 1/F, 108 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, HK 2146 1333 Shop G19 & B01, G/F & B/F, Causeway Bay Plaza 1, 489 Hennessy Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2503 3887 G/F, 541 & 543 Lockhart Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2253 6092 G/F & 2/F, Leighton Centre, 77 Leighton Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2555 0806 G/F & 1/F, 50 Yun Ping Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2501 0281 Shop 118-119, 1/F, Windsor House, 311 Gloucester Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2177 3368 G/F & 1/F, 8 Russell Street, Causeway Bay, H.K. 2702 0533 G/F, 88 Wing Lok Street, Sheung Wan, HK 2253 0071 G/F, 60-62 Yee Wo Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2697 9322 Shop 234-235, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 168-200 Connaught Road Central, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong 2559 1288 Shop 205, Podium Level 2, The Westwood, No. -

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL on TRANSPORT Pedestrian Schemes for Mong Kok and Tsim Sha Tsui Introduction This Paper

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL ON TRANSPORT Pedestrian Schemes for Mong Kok and Tsim Sha Tsui Introduction This paper informs members of the details of the proposed pedestrian schemes for Mong Kok and Tsim Sha Tsui. Background 2. At the meeting of the LegCo Panel on Transport held on 25 February 2000, the Administration presented the objectives and the general concept adopted in devising pedestrian schemes with particular reference to the Causeway Bay scheme as illustration. Members requested the Administration to provide details of the Mong Kok and Tsim Sha Tsui pedestrian schemes for information. Pedestrian Scheme for Mong Kok 3. The pedestrian scheme in Mong Kok covers the area bounded by Argyle Street, Nathan Road, Dundas Street and Fa Yuen Street as shown in Figures 1 and 1A. 4. The substantial commercial, retail and other economic activities in Mong Kok generate significant transport needs, e.g. loading and unloading, access by public transport, and access to car parks. To ensure general access to this area will be maintained, the pedestrian scheme targets the streets where pedestrian activities are most concentrated. Sections of Nelson Street and Soy Street between Nathan Road and Sai Yeung Choi Street South are designated as fully pedestrianised streets. In addition, Tung Choi Street and the section of Sai Yeung Choi Street South between Nelson Street and Soy Street would be designated as part-time pedestrianised streets. Vehicles, other than emergency vehicles, would not be permitted to enter the streets during specified hours, initially between 4 pm to mid-night. 5. The rest of the streets within the area would be designated as mixed priority streets. -

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total No

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total no. of electors: 869) Trade Union Union Name (English) Postal Address (English) Registration No. 7 Hong Kong & Kowloon Carpenters General Union 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. 8 Hong Kong & Kowloon European-Style Tailors Union 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 15 Hong Kong and Kowloon Western-styled Lady Dress Makers Guild 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 17 HK Electric Investments Limited Employees Union 6/F., Kingsfield Centre, 18 Shell Street,North Point, Hong Kong. Hong Kong & Kowloon Spinning, Weaving & Dyeing Trade 18 1/F., Kam Fung Court, 18 Tai UK Street,Tsuen Wan, N.T. Workers General Union 21 Hong Kong Rubber and Plastic Industry Employees Union 1st Floor, 20-24 Choi Hung Road,San Po Kong, Kowloon DAIRY PRODUCTS, BEVERAGE AND FOOD INDUSTRIES 22 368-374 Lockhart Road, 1/F.,Wan Chai, Hong Kong. EMPLOYEES UNION Hong Kong and Kowloon Bamboo Scaffolding Workers Union 28 2/F, Wah Hing Com. Centre,383 Shanghai St., Yaumatei, Kln. (Tung-King) Hong Kong & Kowloon Dockyards and Wharves Carpenters 29 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. General Union 31 Hong Kong & Kowloon Painters, Sofa & Furniture Workers Union 1/F, 368 Lockhart Road,Pakling Building,Wanchai, Hong Kong. 32 Hong Kong Postal Workers Union 2/F., Cheng Hong Building,47-57 Temple Street, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon. 33 Hong Kong and Kowloon Tobacco Trade Workers General Union 1/F, Pak Ling Building,368-374 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong HONG KONG MEDICAL & HEALTH CHINESE STAFF 40 12/F, United Chinese Bank Building,18 Tai Po Road,Sham Shui Po, Kowloon. -

Police Report Rooms Receiving 992 Emergency SMS Service Applications S/N Region Report Room Address of Report Room 1

Police Report Rooms receiving 992 Emergency SMS Service Applications S/N Region Report Room Address of Report Room 1. Central District No.2 Chung Kong Road, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong 2. Peak Sub-Division No.92 Peak Road, Hong Kong 3. Western Division No.280 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 4. Aberdeen Division No.4 Wong Chuk Hang Road , Hong Kong Hong Kong 5. Stanley Sub-Division No.77 Stanley Village Road, Stanley, Hong Kong Island 6. Wan Chai Division No. 1 Arsenal Street, Wanchai, Hong Kong 7. Happy Valley Division No.60 Sing Woo Road, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 8. North Point Division No.343 Java Road, Hong Kong 9. Chai Wan Division No.6 Lok Man Road, Chai Wan , Hong Kong 10. Tsim Sha Tsui Division No.213 Nathan Road, Kowloon 11. Yau Ma Tei Division No.3 Yau Cheung Road, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon 12. Sham Shui Po Division No. 37A Yen chow Street, Kowloon Kowloon 13. Cheung Sha Wan Division No. 880 Lai Chi Kok Road, Kowloon West 14. Mong Kok District No. 142 Prince Edward Road West, Kowloon 15. Kowloon City Division No. 202 Argyle Street, Kowloon 16. Hung Hom Division No.99 Princess Margaret Road, Kowloon 17. Wong Tai Sin District No.2 Shatin Pass Road, Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon 18. Sai Kung Division No.1 Po Tung Road, Sai Kung, Kowloon 19. Kowloon Kwun Tong District No.9 Lei Yue Mun Road, Kwun Tong, Kowloon 20. East Tseung Kwan O District No.110 Po Lam Road North, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon 21. -

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

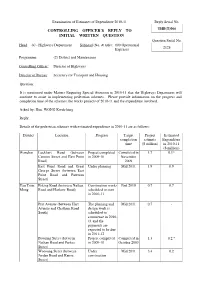

THB(T)066 CONTROLLING OFFICER’S REPLY to INITIAL WRITTEN QUESTION Question Serial No

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2010-11 Reply Serial No. THB(T)066 CONTROLLING OFFICER’S REPLY TO INITIAL WRITTEN QUESTION Question Serial No. Head: 60 - Highways Department Subhead (No. & title): 000 Operational 2128 Expenses Programme: (2) District and Maintenance Controlling Officer: Director of Highways Director of Bureau: Secretary for Transport and Housing Question: It is mentioned under Matters Requiring Special Attention in 2010-11 that the Highways Department will continue to assist in implementing pedestrian schemes. Please provide information on the progress and completion time of the schemes, the works projects of 2010-11 and the expenditure involved. Asked by: Hon. WONG Kwok-hing Reply: Details of the pedestrian schemes with estimated expenditure in 2010-11 are as follows: District Location Progress Target Project Estimated completion estimate Expenditure time ($ million) in 2010-11 ($ million) Wanchai Lockhart Road (between Project completed Completed in 1.7 0.1* Cannon Street and East Point in 2009-10 November Road) 2009 East Point Road and Great Under planning Mid 2011 1.9 0.9 George Street (between East Point Road and Paterson Street) Yau Tsim Peking Road (between Nathan Construction works End 2010 0.7 0.7 Mong Road and Hankow Road) scheduled to start in 2010-11 Prat Avenue (between Hart The planning and Mid 2011 0.7 - Avenue and Chatham Road design work is South) scheduled to commence in 2010 11 and the payments are expected to be due in 2011-12 Bowring Street (between Project completed Completed in 1.3 0.2 -

When Is the Best Time to Go to Hong Kong?

Page 1 of 98 Chris’ Copyrights @ 2011 When Is The Best Time To Go To Hong Kong? Winter Season (December - March) is the most relaxing and comfortable time to go to Hong Kong but besides the weather, there's little else to do since the "Sale Season" occurs during Summer. There are some sales during Christmas & Chinese New Year but 90% of the clothes are for winter. Hong Kong can get very foggy during winter, as such, visit to the Peak is a hit-or-miss affair. A foggy bird's eye view of HK isn't really nice. Summer Season (May - October) is similar to Manila's weather, very hot but moving around in Hong Kong can get extra uncomfortable because of the high humidity which gives the "sticky" feeling. Hong Kong's rainy season also falls on their summer, July & August has the highest rainfall count and the typhoons also arrive in these months. The Sale / Shopping Festival is from the start of July to the start of September. If the sky is clear, the view from the Peak is great. Avoid going to Hong Kong when there are large-scale exhibitions or ongoing tournaments like the Hong Kong Sevens Rugby Tournament because hotel prices will be significantly higher. CUSTOMS & DUTY FREE ALLOWANCES & RESTRICTIONS • Currency - No restrictions • Tobacco - 19 cigarettes or 1 cigar or 25 grams of other manufactured tobacco • Liquor - 1 bottle of wine or spirits • Perfume - 60ml of perfume & 250 ml of eau de toilette • Cameras - No restrictions • Film - Reasonable for personal use • Gifts - Reasonable amount • Agricultural Items - Refer to consulate Note: • If arriving from Macau, duty-free imports for Macau residents are limited to half the above cigarette, cigar & tobacco allowance • Aircraft crew & passengers in direct transit via Hong Kong are limited to 20 cigarettes or 57 grams of pipe tobacco. -

Designated 7-11 Convenience Stores

Store # Area Region in Eng Address in Eng 0001 HK Happy Valley G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK 0009 HK Quarry Bay Shop 12-13, G/F., Blk C, Model Housing Est., 774 King's Road, HK 0028 KLN Mongkok G/F., Comfort Court, 19 Playing Field Rd., Kln 0036 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, TAL Building, 45-53 Austin Road, Kln 0077 KLN Kowloon City Shop A-D, G/F., Leung Ling House, 96 Nga Tsin Wai Rd, Kowloon City, Kln 0084 HK Wan Chai G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK 0085 HK Sheung Wan G/F., Blk B, Hiller Comm Bldg., 89-91 Wing Lok St., HK 0094 HK Causeway Bay Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0102 KLN Jordan G/F, 11 Nanking Street, Kln 0119 KLN Jordan G/F, 48-50 Bowring Street, Kln 0132 KLN Mongkok Shop 16, G/F., 60-104 Soy Street, Concord Bldg., Kln 0150 HK Sheung Wan G01 Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Rd C, HK-Macau Ferry Terminal, HK 0151 HK Wan Chai Shop 2, 20 Luard Road, Wanchai, HK 0153 HK Sheung Wan G/F., 88 High Street, HK 0226 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, Cheung King Mansion, 144 Austin Road, Kln 0253 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui East Shop 1, Lower G/F, Hilton Tower, 96 Granville Road, Tsimshatsui East, Kln 0273 HK Central G/F, 89 Caine Road, HK 0281 HK Wan Chai Shop A, G/F, 151 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, HK 0308 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 1 & 2, G/F, Hart Avenue Plaza, 5-9A Hart Avenue, TST, Kln 0323 HK Wan Chai Portion of shop A, B & C, G/F Sun Tao Bldg, 12-18 Morrison Hill Rd, HK 0325 HK Causeway Bay Shop C, G/F Pak Shing Bldg, 168-174 Tung Lo Wan Rd, Causeway Bay, HK 0327 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 7, G/F Star House, 3 Salisbury Road, TST, Kln 0328 HK Wan Chai Shop C, G/F, Siu Fung Building, 9-17 Tin Lok Lane, Wanchai, HK 0339 KLN Kowloon Bay G/F, Shop No.205-207, Phase II Amoy Plaza, 77 Ngau Tau Kok Road, Kln 0351 KLN Kwun Tong Shop 22, 23 & 23A, G/F, Laguna Plaza, Cha Kwo Ling Rd., Kwun Tong, Kln. -

Participating Sellers District Participating Designated Physical Stores / Other Sales Channels Shop 410, Cityplaza, Taikoo Shing, Hong Kong

Participating Sellers District Participating Designated Physical Stores / Other Sales Channels Shop 410, Cityplaza, Taikoo Shing, Hong Kong Shop 814-816, 8/F, Times Square, 1 Matheson Street, Hong Kong Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Island Basement, Hang Lung Centre, 2-20 Paterson Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong G/F, Hang Lung Centre, 2-20 Paterson Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Shop MTR-02, Festival Walk, 80 Tat Chee Road, Kowloon Tong, Kowloon Shop G22, Telford Plaza I, Kowloon Bay, Kowloon Shop G44, Telford Plaza I, Kowloon Bay, Kowloon G/F, 58-60 Cameron Road, Tsim Sha Shui, Kowloon Shop 341, 3/F, Ocean Centre, Harbour City, Tsim Sha Shui, Kowloon Shop MTR 14, iSQUARE, 63 Nathan Road, Tsim Sha Shui, Kowloon Basement, B2, 13 Sai Yeung Choi Street South, Mong Kok, BROADWAY PHOTO Kowloon Kowloon SUPPLY LTD G/F, 13 Sai Yeung Choi Street South, Mong Kok, Kowloon G/F, 78 Sai Yeung Choi Street South, Mong Kok, Kowloon G/F-3/F, 80 Sai Yeung Choi Street South, Mong Kok, Kowloon G/F-3/F, 79 Argyle Street, Mong Kok, Kowloon G/F-2/F, 28 Soy Street, Mong Kok, Kowloon Xsite 2 & 2A, 5/F, APM, Millennium City 5, Kwun Tong, Kowloon Shop 204, 2/F, Plaza Hollywood, Diamond Hill, Kowloon Shop 428-430, 4/F, Landmark North, Sheung Shui, New Territoires New Shop 210-213, 2/F, Metropolis Plaza, Sheung Shui, Territories New Territories Shop G17, Tuen Mun Town Plaza, Phase 1, Tuen Mun, New Territories Participating Sellers District Participating Designated Physical Stores / Other Sales Channels Shop G031, Tuen Mun Town Plaza, Phase 1, Tuen Mun, New Territories Shop A-C & D7, G/F-3/F, Lok Sing Building, 16 Kau Yuk Road, Yuen Long, New Territories BROADWAY PHOTO Shop 611, 6/F, New Town Plaza, Phase I, Sha Tin, SUPPLY LTD New Territories Shop 136, 1/F, Maritime Square, Tsing Yi, New Territories New Territories Shop A-C, G/F-2/F, Tak Yan House, 43-45 Chung On Street, Tsuen Wan, New Territories Shop 218, 2/F, East Point City, Tseung Kwan O, New Territories . -

Facilities in Henry G. Leong Yaumatei Community Centre and Exemptions from Payment of Charges for Use of Facilities

Annex A(I) Facilities in Henry G. Leong Yaumatei Community Centre and Exemptions from Payment of Charges for Use of Facilities (1) Facilities in Henry G. Leong Yaumatei Community Centre Facility Features Multi-purpose Hall The seating capacity is up to 522, including 360 movable seats in the 1/F Hall and 162 fixed seats in the 3/F Balcony. There are 4 additional wheelchair spaces in the Balcony. The 1/F Hall can accommodate up to a maximum of 400 persons, while the 3/F Balcony can accommodate up to 176 persons, including no more than 10 standing staff of the hirer. The minimum number of participants for use of the Multi-purpose Hall is 50. Chairs, tables, exhibition boards, A4/A1 display stands, DVD player, cassette player, lighting system, sound system, piano, projector and stage banner gallows are available (Remark: Technical information of the Hall is detailed at Annex A(IV)). Hirers should deploy their own qualified technicians to operate the lighting and sound consoles as well as arrange seats and conduct venue clearance after use by themselves. Hirers are liable to compensate any damage caused to the facilities. Conference Room* The room, the floor area of which is about 95m2, has a seating capacity of about 120 persons. The conference table has a seating capacity of about 22 persons. Folding tables (6 pieces), chairs (120 pieces), basic PA system (2 wireless microphones), whiteboard, multi-media projector and screen are available. Classroom *# The room, the floor area of which is about 57m2, has a seating capacity of about 50 persons. -

Minutes of the 17 Meeting of the District Facilities Management

Minutes of the 17th Meeting of the District Facilities Management Committee of the Yau Tsim Mong District Council (2016-2019) Date : 6 December 2018 (Thursday) Time : 2:30 p.m. Venue : Yau Tsim Mong District Council Conference Room 4/F, Mong Kok Government Offices 30 Luen Wan Street Mong Kok, Kowloon Present: Chairman Mr CHOI Siu-fung, Benjamin Vice-chairman Mr JO Chun-wah, Craig District Council Members Mr IP Ngo-tung, Chris, JP Ms KWAN Sau-ling Ms WONG Shu-ming, MH Mr LAM Kin-man Mr CHAN Siu-tong, MH, JP Mr LAU Pak-kei Mr CHOW Chun-fai, BBS, JP Ms TANG Ming-sum, Michelle Mr CHUNG Chak-fai Mr WONG Kin-san Mr CHUNG Kong-mo, BBS, JP Mr YEUNG Tsz-hei, Benny, MH Mr HUI Tak-leung Mr YU Tak-po, Andy Mr HUNG Chiu-wah, Derek Co-opted Members Mr CHAN Sik-ming Mr IP Siu-tak Mr SIU Hon-ping Mr CHAN Tak-lap Mr LEUNG Yiu-wah, Jackie Ms CHIN Pui-kwan Mr LEUNG Yui Representatives of the Government Miss PONG Kin-wah, Assistant District Officer (Yau Tsim Home Affairs Department Katherine Mong) (1) Ms PONG Sze-wan, Senior Executive Officer (District Home Affairs Department Cecilia Management) (Acting), Yau Tsim Mong District Office Ms HO Wing-sze, Senior Manager (Kowloon West/ Leisure and Cultural Marianna Cultural Services) Services Department Mrs CHU LEE Mei-foon, Senior Librarian (Yau Tsim Mong) Leisure and Cultural Karen Services Department Mr LI Kuen-fat District Leisure Manager (Yau Tsim Leisure and Cultural Mong) Services Department Ms CHIU Shui-man, Deputy District Leisure Manager Leisure and Cultural Tabitha (District Support) Yau Tsim Mong Services