Guest Editorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasure Is Where You Find It

TREASURE I S W HER E YOU FIN D IT Williaa Cowie Residenoe Northeast corner o£ Canfield Avenue We.t and Third Avenue Built in 1676 - Razed after 1957 1'rom ~ '!istoQ: ~ Detro! t ~ Michigan by Silas F .......r Volume I, 1689, page 420 Publication underwritten by a grant trom The Hiatorio Memorials Sooiety in Detroit, Miohigan April 1969 OUTLINE HISTORY OF CANFIELD AVENUE WEST BETWEEN SECOND BOULEVARD AND THIRD AVENUE IN HONOR OF ITS ONE HUNDREDTH BIRTHDAY 1869 - 1969 by Mrs. Henry G. Groehn One lovely Wednesday afternoon, in the 1870's, two little girls sat on the McVittie front steps on the south side of Canfield Avenue West, between Second Boulevard and Third Avenue. They were watching the carriagos and horses as they clip-clopped to a stop in front of the Watton carriage stone next door. The ladies in elegant afternoon attire were "com!"" to call" on Mrs. Walter I"atton, the wife of a prominent Detroit denti"t.. Wednesday was the day Mrs. Watton IIreceived," and this was duly noted in a Detroit society blue book, which was a handy reference book for the lIin societyll ladies. Once again, almost one hundred years later, the atmosphere of ele gantly built homes with beautiful, landscaped lawns and quiet living can become a reality on tilis block. The residents who are now rehe.bilitating these homes are recognizing the advantage of historic tOlm house lh-;.ng, wi th its proximity to the center of business, cultural, and educati'm"~_ facilities. Our enthusiasm has blossomed into a plan called the CanfIeid West-Wayne Project, because we desire to share with others our discovery of its unique historical phenomenon. -

American City: Detroit Architecture, 1845-2005

A Wayne State University Press Copyrighted Material m er i ca n Detroit Architecture 1845–2005 C Text by Robert Sharoff Photographs by William Zbaren i ty A Painted Turtle book Detroit, Michigan Wayne State University Press Copyrighted Material Contents Preface viii Guardian Building 56 Acknowledgments x David Stott Building 60 Introduction xiii Fisher Building 62 Horace H. Rackham Building 64 American City Coleman A. Young Municipal Center 68 Fort Wayne 2 Turkel House 70 Lighthouse Supply Depot 4 McGregor Memorial Conference Center 72 R. H. Traver Building 6 Lafayette Park 76 Wright-Kay Building 8 One Woodward 80 R. Hirt Jr. Co. Building 10 First Federal Bank Building 82 Chauncey Hurlbut Memorial Gate 12 Frank Murphy Hall of Justice 84 Detroit Cornice and Slate Company 14 Smith, Hinchman, and Grylls Building 86 Wayne County Building 16 Kresge-Ford Building 88 Savoyard Centre 18 SBC Building 90 Belle Isle Conservatory 20 Renaissance Center 92 Harmonie Centre 22 Horace E. Dodge and Son Dime Building 24 Memorial Fountain 96 L. B. King and Company Building 26 Detroit Receiving Hospital 98 Michigan Central Railroad Station 28 Coleman A. Young Community Center 100 R. H. Fyfe’s Shoe Store Building 30 Cobo Hall and Convention Center 102 Orchestra Hall 32 One Detroit Center 104 Detroit Public Library, Main Branch 34 John D. Dingell VA Hospital Cadillac Place 38 and Medical Center 106 Charles H. Wright Museum Women’s City Club 40 of African American History 108 Bankers Trust Company Building 42 Compuware Building 110 James Scott Fountain 44 Cass Technical High School 112 Buhl Building 46 Detroit Institute of Arts 48 Index of Buildings 116 Fox Theatre 50 Index of Architects, Architecture Firms, Penobscot Building 52 Designers, and Artists 118 Park Place Apartments 54 Bibliography 121. -

Congress! on Al Record-Senate

3108 CONGRESS! ON AL RECORD-SENATE. FE~RUARY" 19, 1660. By 1\fr. WINSLO'V: Petition of 23 citizens of Worcester, 1682. Also, petition of Paul Schulze Baking Co., Chicago, ill., 1\Iass., .fo:r the support of House bill No. 1112; to the Committee urging the passage of the Gronna bill, terminating the wheat on the Judiciar~. guaranty period; to the Committee on Ways and Means. 1661. By Mr. YATES : Petition of J. 1\1. Ocheltree and others of 1683. Also, petition of Tonk Manufacturing Co., urging the / Homer, Ill., urging universal military training; to the Com passage of House bill 10650, and opposing House bill 10615, be Dlittee on Military Affairs. lieving it would be unfair to establish furniture factories in ~662. Also petition of furniture and casket manufacturers of Federal prisons; to the Committee on the Judiciary. Chicago protesting against House bill 10615 ; to the Committee 1684. Also, petition of the Moline Branch National AS O· on the Judiciary. elation for the Advancement of the Colored People. r pre 1663. Also, petition of C. F. Wolff & Son. of Chicago, protesting sentillg 250 citizens of Rock Island, urging the passage of the against legislation favoring labor organizations; to the Com Dyer bill, or some legislation on lynchings; to the Committee mittee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. .on the Judiciary. 1664. Also, petition of Belden l\lanufacturin_g Co., of Chicago, Ill., urging legislation preventing strikes, in the present railroad bill; to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. SENATE. 1665. Also., petition of l\Ianz Engraving Co., by F. -

Weil and Company-Gabriel Richard Building

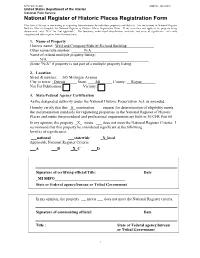

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Weil and Company/Gabriel Richard Building______________ Other names/site number: _ N/A___________________ Name of related multiple property listing: _____N/A____________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __305 Michigan Avenue___________________________________ City or town: _Detroit______ State: ____MI______ County: __Wayne_______ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NATIONAL REGISTER, HISTORY & EDUCATION This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for in ividual propgjJ|1©WALd^iefe.aa^Vteiructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bull shritem- by rTrarMiiyV in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. historic name Ford Motor Company Service Building_____________ other name/site number Envirotech Research Building, EIMCO Building______ street& town 280 South 400 West not for publication city or town Salt Lake City vicinity state Utah code UT county Salt Lake code 035 zip code 84101 As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ nomination n request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, -

Spectacular Fire Ruins Egan Ford Building Here

770,000 dimes, 308,000 quarters. and one penny (Excedrin headache No. 150,000 for manager of bank at Ovid) By LOWELL G. RINKER I never would have accepted it had I known what call that the money was in Ovid waiting to be un determination, It became the duty of the country comfortable in there for a while until the dust Editor it was all about. And I would not wish it on any loaded and stored. ToTabor'ssurprise,hefound treasurer in the county where the money was died down. We used a square quarter-inch body." a. heavy equipment truck parked at the side of stored to come in and make an inventory. screen to screen the dust out." OVID—One of the great fascinating untold The story he tells is fascinating, even if it the bank. On it was a single wooden box about "It was just like opening a lock box, actual A machine was used to count the coins, but stories of the year 1968 can now he told. It in Isn't complete. For understandable reasons, six by 10 feet in size, filled with bags of silver ly," Tabor pointed out. "She (Mrs Velma Beau- even then it took a long time. Three minutes volved more than a million dimes and quarters, Tabor is not disclosing the names of the people coins! fore, Clinton County treasurer) would make an were necessary to count $1,000 in quarters, and plus one penny and probably a hottle of Excedrin. involved nor even where they're from. -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Ford Piquette

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No. 1024-0018 FORD PIQUETTE AVENUE PLANT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Ford Piquette Avenue Plant Other Name/Site Number: Studebaker Detroit Service Building 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 411 Piquette Avenue Not for publication: City/Town: Detroit Vicinity: State: Michigan County: Wayne Code: 163 Zip Code: 48202 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): J_ Public-Local: _ District: _ Public-State: _ Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 _ buildings _ sites _ structures _ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Designated a NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK on FEB 1 7 2006 by the Secretary of the Interior NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORD PIQUETTE AVENUE PLANT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Candidate Committee Cover Page

MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF STATE 1. Committee I.D. Number 82-155706 BUREAU OF ELECTIONS 2. Committee Name Michael Duggan for Mayor Committee CANDIDATE COMMITTEE COVER PAGE Report must be legible, typed or printed in ink and signed by the treasurer(or designated record keeper)and candidate. 3. This Statement covers from: 08/27/2013 to 10/20/2013 1. Committee I.D. Number 4. Candidate Last Name First Name M.I. 82-155706 Duggan Michael E. 2. Committee Name 4a. Office Sought Including District # or Community Served (If applicable) Michael Duggan for Mayor Committee City , Detroit - At Large , City Mayor 5. Committee's Mailing Address 6. Treasurer's Name & Residential Address 2751 E. Jefferson Ave, 5th Floor, Detroit, MI 48207 Williams, Dr. Rebecca , 675 Pallister St., Detroit, MI 48202 Area Code and Phone: (313) 324-8901 If the address in this box is different from the committee Area Code and Phone: (313) 324-8901 mailing address on the Statement of Organization, mail may be sent to this address by the filing official 7. Designated Record keeper's Name and Mailing Address (If the committee has a Designated Record keeper) Area Code and Phone: 8. TYPE OF STATEMENT Effective Date of Dissolution 10/20/2013 Pre General By checking this item, I/we certify that the committee has no assets or outstanding debts, including late filing fees. Further, I/We request that if the dissolution cannot be granted, Date of Election, Convention or Caucus that this be considered a request for the Reporting Waiver. Note: The disposition of residual funds must be reported on Schedule 1B and the 11/05/2013 Summary Page. -

The Lawyers Club, 1947-1948 University of Michigan Law School

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Miscellaneous Law School Publications Law School History and Publications 1948 The Lawyers Club, 1947-1948 University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.umich.edu/miscellaneous Part of the Legal Education Commons Citation University of Michigan Law School, "The Lawyers Club, 1947-1948" (1948). Miscellaneous Law School Publications. http://repository.law.umich.edu/miscellaneous/41 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School History and Publications at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Miscellaneous Law School Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. H LAWYERS LU NIVE SI ICHI Table of PAGE OFFICERS. 6 BOARD OF C:·OVERNORS CoMl\HTTEEs 8 STUDENT COUNCIL. 9 FORMER OFFICERS . 10 FORMER MEMBERS OF THE HOARD O:F GOVERNORS 11 FORMER PRESIDENTS OF THE STUDENT COUNCIL 13 CoNi>TITUTION AND BY-LAws 15 HONORARY MEMBERS 36 LAWYER MEMBERS 48 STUDENT MEMBERS 62 JN MEMORIAM MEMBERS 73 6 OFFICERS Officers ex officio HoN. LELAND W. CARR Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Michigan! HoN. GEORGE E. BusHNELL Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Michigan2 President Eow ARD S. RoGERS GROVER c. GRISMORE I During HJ47 2 During 1948 THE LAWYERS CLUB 7 Court of the State HoN. LELAND W. Chief 1!H7 HoN. GEORGE E. BUSHNELL, Chief 1948 HoN. WALTER H. NoRTH firom the Board HoN. J. HERBERT The P1esident of the ALEXANDER G. -

Permanent Historic Designation Study Report

PERMANENT HISTORIC DESIGNATION STUDY REPORT FIRST NATIONAL BANK/FIRST WISCONSIN NATIONAL BANK BUILDING 733-743 N. WATER STREET JUNE 2007 INTERIM HISTORIC DESIGNATION STUDY REPORT I. NAME Historic: First National Bank Building First Wisconsin National Bank Building Common Name: 735 N. Water Street II. LOCATION 733-743 N. Water Street Legal Description - Tax Key No: 392-0601-110-x Plat of Milwaukee in SECS (28-29-33)-7-22 Block 2 Lots 1 & 2 III. CLASSIFICATION Building IV. OWNER Compass Properties North Water St. LLC 735 N. Water Street #1225 Milwaukee, WI 53202 ALDERMAN Ald. Robert Bauman 4th Aldermanic District NOMINATOR Donna Schlieman V. YEAR BUILT 1912-1914 (Permit dated July 15, 1912, permit notes) ARCHITECT: D. H. Burnham & Co., Chicago (Permit) VI. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION The First National/First Wisconsin National Bank building is located at the southwest corner of N. Water and E. Mason Streets in the heart of the Central Business District. It occupies its entire site with no setbacks for landscaping. The west façade fronts directly onto the Milwaukee River. The surrounding blocks are commercial in character with buildings ranging in age from the 1870s to the 1990s. Architectural styles reflect their period of construction and range from Italianate to Post Modern. The First National/First Wisconsin National Bank is a sixteen story, flat roofed building, U-plan in shape with a south facing light court not visible from Water Street. The granite, pressed buff brick and terra cotta masonry exterior is applied over a steel skeletal frame. The building is arranged in the traditional tripartite fashion with a base, shaft and ornamental top. -

In Re DBOPC Regular Meeting 09-21-2017

9/21/2017 Page 1 DETROIT BOARD OF POLICE COMMISSIONERS REGULAR MEETING THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 2017 at 6:30 PM OPERATING ENGINEERS LOCAL 324 1550 HOWARD STREET DETROIT, MICHIGAN 48226 9/21/2017 Page 2 1 COMMISSIONERS: 2 3 RICHARD SHELBY, Commissioner (Dist. 1) 4 REGINALD CRAWFORD, Commissioner (Dist. 3) 5 WILLIE BELL, Commissioner (Dist. 4) 6 LISA CARTER, Chairperson (Dist. 6) 7 DEREK SANDERS, At-Large 8 EVA GARZA DEWAELSCHE, At Large/Vice Chair 9 ELIZABETH BROOKS, At-Large 10 11 BOARD SECRETARY: GREGORY HICKS 12 HUMAN RESOURCES: ROBERT BROWN 13 14 REPRESENTING THE CHIEF OF POLICE'S OFFICE: 15 CHIEF JAMES E. CRAIG 16 FIRST ASSISTANT CHIEF LASHINDA STAIR 17 COMMANDER TODD BETTISON 18 ASSISTANT CHIEF ARNOLD WILLIAMS 19 DEPUTY CHIEF WILLIAM FITZGERALD 20 DEPUTY CHIEF LeVALLEY, ET AL 21 22 23 24 25 9/21/2017 Page 3 1 Detroit, Michigan 2 Thursday, September 21, 2017 3 6:31 p.m. 4 THE CHAIRPERSON: Good evening. Welcome to 5 the Board of Police Commissioners' monthly community 6 meeting. I am Lisa Carter. Could you please keep the 7 noise down. We've started our meeting. Thank you. 8 Welcome to the monthly Board of Police 9 Commissioners' community meeting. My name's 10 Lisa Carter, Chair for the Commission. At this time, 11 I'm going to ask that -- 12 Commissioner Bell? 13 COMM. BELL: There's no chaplain or minister 14 in the house or deacon in the house. If not, let us 15 pray. 16 (Invocation given.) 17 THE CHAIRPERSON: At this time we'll start 18 with introductions from -- to my far left. -

Document.Pdf

FORD BUILDING 615 griswold street 1 why the ford building 2 ford building history 3 city & building access 4 neighborhood 5 building amenities 6 typical floor plan 1 why the ford building Be a part of Detroit’s future while remaining rooted in its’ historic past... With a rapidly growing diverse and energetic workforce living in downtown Detroit, an increasing number of businesses, start-ups, and entrepreneurs are moving to the city to attract talented employees. Amongst this flourishing activity, the Ford Building shines with direct access to Detroit’s world-class cultural institutions, professional sports teams, open space and a great variety of restaurants and entertainment venues. A surge of commercial and residential construction projects are planned, building on the resources of the downtown district. Recently acquired in the summer of 2017, our experienced and enthusiastic development group is committed to providing class A office space with world-class amenities in a fully modernized, yet stately historic context. Located at the heart of Detroit’s growing and vibrant downtown, the Ford Building’s central location is perfectly situated to provide direct access by car, and to the surrounding city by foot and public transportation. Be a part of the Ford Building, and be a part of photo credit: Jason Keen Detroit! aerial photo - downtown detroit 4 ford building approach to ford building from griswold street - rendering 615 griswold street 5 2 ford building history daniel burnham, 1908 Once toted as “one of the most complete and elaborate office buildings in the world”, the Ford Building has been an integral part of the fabric of downtown Detroit since its opening in 1908.