A Family Affair-Military Service in the Postwar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doc Mcstuffins

www.usc.edu/hhs What's New Follow HH&S What a difference a year makes! We launched our new website, and supplemented that with Facebook and Twit- The Numbers ter pages, which are also new. We pioneered our StoryBus Tours, helping writers find inspiration on the streets of East Los Angeles. Farther from home, I took writers on fact-finding trips to Mumbai and South Africa—and held follow-up panel discussions at the Writers Guild of America, West (WGAW). We continued our global outreach by organizing a trip with 200 HH&S-assisted storylines Chris Keyser, president of the WGAW, and three writers and producers to the 5th International Entertainment Education Conference in Delhi, India, which was co-sponsored by Holly- events wood, Health & Society, and moderated a panel on youth en- held trepreneurship and media at the Unesco Youth Forum in Paris. Because HH&S maintains long-standing, far-reaching ties with 9 members of both the entertainment and public health com- munities—contacts that continue to grow—we remain well- positioned to continue to lead as CDC’s primary partner in the field of entertainment education. director, Hollywood, Health & Society 887links on TV/ film websites Trips to EE5, India & South Africa 600% increase in TV episodes tackling key global health topics since It was a year for stretching our HH&S outreach began in 2008 wings. In November, four writers and producers were joined by HH&S Director Sandra de Castro tipsheets on priority Buffington at the 5th Interna- health topics tion Entertainment Education Conference in Delhi, participat- 35 ing in storytelling workshops Mumbai panel discussion and panel talks. -

WORST COOKS in AMERICA: CELEBRITY EDITION Contestant Bios

Press Contact: Lauren Sklar Phone: 646-336-3745; Email: [email protected] WORST COOKS IN AMERICA: CELEBRITY EDITION Contestant Bios MINDY COHN Mindy Cohn made her acting debut as the witty, precious Eastland Academy student Natalie Green in the hit comedy series The Facts of Life. She was discovered while attending Westlake School for Girls in Bel Air, California, when actress Charlotte Rae and producer Norman Lear came to the school to authenticate scripts for their new show. Ms. Rae was so taken with the vivacious eighth grader she convinced producers to create a role for her. Mindy remained on the show for all nine seasons, also traveling to Paris and Australia with her co-stars to produce two successful television movies based on the series. Concurrently, with her role in Facts, Mindy played “Rose Jenko” in Fox’s 21 Jump Street. Other notable television appearances included Diff’rent Strokes, Double Trouble, Charles in Charge, Dream On and Suddenly Susan. In 1983, Mindy appeared in her first professional stage performance in Table Settings, written and directed by James Lapine and filmed for HBO Television. The illustrious cast included Eileen Heckart, Stockard Channing, Robert Klein, Peter Riegart, and Dinah Manoff. She went on to make her feature film debut in The Boy Who Could Fly, which co-starred Colleen Dewhurst, Fred Gwynne and Fred Savage. Mindy took a hiatus from her career to attend university, where she earned a Bachelor’s degree in Cultural Anthropology and a Masters in Education. During this time, she studied improvisation and scene work with Gary Austin and Larry Moss. -

Lt. Dan Rocks Out

HIGH DESERT WARRIOR Volume 6, Number 11 www.irwin.army.mil March 18, 2010 Published in the interest of the National Training Center and Fort Irwin community Change of Responsibility 916th Support Brigade will hold a Bri- gade Command Sergeant Major Change of Responsibility ceremony. The ceremony will take place on Monday, 4 p.m., at Jack Rabbit Park. Legal Assistance Hours Fort Irwin Legal Assistance Office hours have changed. The new schedule is as follows: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday: 8 a.m.-4:30 p.m.; Thursday: 8 a.m.-3 p.m. Notary Services: 8 a.m.-3 p.m., Everyday, walk-in basis. Appointment calendars open: Fridays at 1 p.m. Audie Murphy Club Members of the Sgt. Audie Murphy Club will hold its monthly meeting at the SAMC Hall, located at the NTC Museum, Bldg. 587, Room 11, 12-1 p.m., March 30. For more information, contact Sgt. 1st Class Catherine Harris at 380-8386. Battle Staff Graduation Fort Irwin community is invited to at- tend the graduation ceremony of noncom- Actor Gary Sinese, performs with the Lt. Dan Band at Fort Irwin’s Army Field, March 12. The Lt. Dan Band performed a free missioned officers who will graduate from concert for the Fort Irwin community as part of his 41st USO tour. See more photos on Pages 10 and 11. Battle Staff Class 14-10 at the Post Theater, at 9 a.m., March 26. For more information, call 380-3880. Lt. Dan rocks out NTC STORY AND PHOTOS mate message to troops and their families is that was cut short because he got injured and lost Puerto Rican Birth Certificates BY SGT. -

SPRING 2017 MESSAGE from the CHAIRMAN Greetings to All USAWC Graduates and Foundation Friends

SPRING 2017 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Greetings to all USAWC graduates and Foundation friends, On behalf of our Foundation Board of Trustees, it is a privilege to share Chairman of the Board this magazine with you containing the latest news of our Foundation LTG (Ret) Thomas G. Rhame and of the U.S. Army War College (USAWC) and its graduates. Vice Chairman of the Board Our Spring Board meeting in Tampa in March was very productive as we Mr. Frank C. Sullivan planned our 2018 support to the College. We remain very appreciative Trustees and impressed with the professionalism and vision of MG Bill Rapp, LTG (Ret) Richard F. Timmons (President Emeritus) RES ’04 & 50th Commandant as he helps us understand the needs of MG (Ret) William F. Burns (President Emeritus) the College going forward. With his excellent stewardship of our Foundation support across Mrs. Charlotte H. Watts (Trustee Emerita) more than 20 programs, he has helped advance the ability of our very successful public/ Dr. Elihu Rose (Trustee Emeritus) Mr. Russell T. Bundy (Foundation Advisor) private partnership to provide the margin of excellence for the College and its grads. We also LTG (Ret) Dennis L. Benchoff thank so many of you who came to our USAWC Alumni Dinner in Tampa on March 15, Mr. Steven H. Biondolillo 2017 (feature and photos on page 7). Special thanks to GEN Joseph L. Votel III, RES ’01, Mr. Hans L. Christensen and GEN Raymond A. Th omas III, RES ’00, for hosting us at the Central and Special Ms. Jo B. Dutcher Operations Commands at MacDill AFB on March 17th. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Artistry of the Guard

Family Magazine, Fall 2008 Artistry of the Guard Fall 2008 STANHOPE S. SPEARS MAJOR GENERAL THE ADJUTANT GENERAL From the Desk of The Adjutant General I recently had the honor of presenting Mr. Craig Melvin with The Palmetto Patriot Award for his demonstrated commitment to telling the S.C. National Guard story. Many of you in the Midlands are familiar with his fair and balanced ational reporting as an anchor here in Columbia with N WIS-TV. Craig’s been a leader in reporting on all aspects of our Citizen-Soldiers and Airmen, their families and employers throughout our nation’s Global War on Terrorism. Even though Craig istorian recently left his anchor position at WIS for a H new position in Washington, D.C., he was quick hoto by Maj. Scott Bell, S.C. to tell me he will never forget the Soldiers and P Guard families of the S.C. National Guard. I feel Craig’s sentiment was sincere. Our Citizen-Soldiers are the best this nation has to give and I hope he will continue telling his audiences about the selfless, patriotic character of our Soldiers and Airmen in the National Guard. Concerning your selflessness, my wife Dot and I thank you from the bottom of our hearts for the tremendous outpouring of love, support and prayers you have shared with us following the loss of our son Stan, Jr. to a heart attack. We appreciate your kindness more than you know. As this year’s hurricane season starts to heat up, I hope everyone will take the time to review the Family Emergency Kit information on page four of this magazine. -

Lee Edwards Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5q2nf31k No online items Preliminary Inventory of the Lee Edwards papers Finding aid prepared by Hoover Institution Library and Archives Staff Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2009, 2013 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Preliminary Inventory of the Lee 2010C14 1 Edwards papers Title: Lee Edwards papers Date (inclusive): 1878-2004 Collection Number: 2010C14 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 389 manuscript boxes, 12 card file boxes, 2 oversize boxes, 5 film reels, 1 oversize folder(146.4 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, speeches and writings, memoranda, reports, studies, financial records, printed matter, and sound recordings of interviews and other audiovisual material, relating to conservatism in the United States, the mass media, Grove City College, the Heritage Foundation, the Republican Party, Walter Judd, Barry Goldwater, and Ronald Reagan. Includes extensive research material used in books and other writing projects by Lee Edwards. Also includes papers of Willard Edwards, journalist and father of Lee Edwards. Creator: Edwards, Lee, 1932- Creator: Edwards, Willard, 1902-1990 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please -

Trump's Generals

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE Trump’s Generals: A Natural Experiment in Civil-Military Relations JAMES JOYNER Abstract President Donald Trump’s filling of numerous top policy positions with active and retired officers he called “my generals” generated fears of mili- tarization of foreign policy, loss of civilian control of the military, and politicization of the military—yet also hope that they might restrain his worst impulses. Because the generals were all gone by the halfway mark of his administration, we have a natural experiment that allows us to com- pare a Trump presidency with and without retired generals serving as “adults in the room.” None of the dire predictions turned out to be quite true. While Trump repeatedly flirted with civil- military crises, they were not significantly amplified or deterred by the presence of retired generals in key roles. Further, the pattern continued in the second half of the ad- ministration when “true” civilians filled these billets. Whether longer-term damage was done, however, remains unresolved. ***** he presidency of Donald Trump served as a natural experiment, testing many of the long- debated precepts of the civil-military relations (CMR) literature. His postelection interviewing of Tmore than a half dozen recently retired four- star officers for senior posts in his administration unleashed a torrent of columns pointing to the dangers of further militarization of US foreign policy and damage to the military as a nonpartisan institution. At the same time, many argued that these men were uniquely qualified to rein in Trump’s worst pro- clivities. With Trump’s tenure over, we can begin to evaluate these claims. -

Lessons-Encountered.Pdf

conflict, and unity of effort and command. essons Encountered: Learning from They stand alongside the lessons of other wars the Long War began as two questions and remind future senior officers that those from General Martin E. Dempsey, 18th who fail to learn from past mistakes are bound Excerpts from LChairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: What to repeat them. were the costs and benefits of the campaigns LESSONS ENCOUNTERED in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what were the LESSONS strategic lessons of these campaigns? The R Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University was tasked to answer these questions. The editors com- The Institute for National Strategic Studies posed a volume that assesses the war and (INSS) conducts research in support of the Henry Kissinger has reminded us that “the study of history offers no manual the Long Learning War from LESSONS ENCOUNTERED ENCOUNTERED analyzes the costs, using the Institute’s con- academic and leader development programs of instruction that can be applied automatically; history teaches by analogy, siderable in-house talent and the dedication at the National Defense University (NDU) in shedding light on the likely consequences of comparable situations.” At the of the NDU Press team. The audience for Washington, DC. It provides strategic sup- strategic level, there are no cookie-cutter lessons that can be pressed onto ev- Learning from the Long War this volume is senior officers, their staffs, and port to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman ery batch of future situational dough. The only safe posture is to know many the students in joint professional military of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified com- historical cases and to be constantly reexamining the strategic context, ques- education courses—the future leaders of the batant commands. -

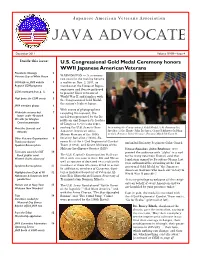

JAVA Advocate, December 2011 Edition

Japanese American Veterans Association JAVA ADVOCATE December 2011 Volume XVIIII—Issue 4 Inside this issue: U.S. Congressional Gold Medal Ceremony honors WWII Japanese American Veterans President’s Message 2 Veterans Day at White House WASHINGTON — A ceremony two years in the making became CGM info on JAVA website 3 a reality on Nov. 2, 2011, as Regional CGM programs members of the House of Repre- sentatives and Senate gathered CGM (continued from p. 1) 4 to present Nisei veterans of World War II and families with High praise for CGM events 5 the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest honor. JAVA members photos 6 With scores of photographers Wakatake receives best 7 recording the moment, the lawyer under 40 award medal was presented by the Re- Wreaths for Arlington publican and Democratic leaders Cemetery gravesites of Congress to veterans repre- Meet the Generals and 8 senting the U.S. Army’s three Presenting the Congressional Gold Medal, L-R: Susumu Ito, Admirals Japanese American units: Speaker of the House John Boehner, Grant Ichikawa (holding Mitsuo Hamasu of the 100th medal), Senator Daniel Inouye, Senator Mitch McConnell. Other Veterans Organizations 9 Infantry Battalion (100th), Su- Thank you donors! sumu Ito of the 442nd Regimental Combat ion/442nd Infantry Regiment Color Guard. Speakers Bureau photo Team (442nd), and Grant Ichikawa of the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). House Speaker John Boehner, who Tucci wins award for SGT 10 greeted the audience with “aloha” in a nod Rock graphic novel The U.S. Capitol’s Emancipation Hall was to the many vets from Hawaii, said that Wanted: Stories about you! filled with veterans in their 80s and 90s as legislation signed by President Obama last well as spouses of deceased vets and family year authorized the awarding of the Con- Speakers Bureau photos 11 members of those who were killed in action. -

1999 Annual Report

Army and Air Force Mutual Aid Association 121st Annual Report For the year ended 31 December 1999 1879 OVER 120 YEARS OF SERVICE 1999 Organized 13 January 1879 121st Annual Report For the year ended 31 December 1999 Army and Air Force Mutual Aid Association 102 Sheridan Avenue Fort Myer, Virginia 22211-1110 Branch office located in Pentagon Concourse (north end) Toll free: 1-800-336-4538 Local: 703-522-3060 (recorded messages after hours) FAX: 703-522-1336 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.aafmaa.com Office hours: 8:30 A.M.–4:30 P.M. EST Monday–Friday Night depository at both locations 1 2 3 ASSOCIATION DIRECTORS CHAIR General Robert W. Sennewald VICE CHAIR Lieutenant General Donald M. Babers BOARD OF DIRECTORS Term expires 2001: Lieutenant General Donald M. Babers Terms expire 2002: Lieutenant General Henry Doctor, Jr. Colonel Wayne T. Fujito Lieutenant General Bradley C. Hosmer Major General Susan L. Pamerleau* Captain Bradley J. Snyder, CLU Terms expire 2003: Major William D. Clark Major Joe R. Reeder Command Sergeant Major Jimmie W. Spencer Terms expire 2004: General Michael P.C. Carns Lieutenant General John A. Dubia Major General Michael J. Nardotti, Jr. Brigadier General L. Donne Olvey Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force Sam E. Parish General Robert W. Sennewald CHAIRS EMERITI General Walter T. Kerwin, Jr. General Michael S. Davison DIRECTORS EMERITI General John R. Guthrie Brigadier General Elizabeth P. Hoisington ASSOCIATION OFFICERS President Captain Bradley J. Snyder, CLU Vice President for Services & Secretary Major Joseph J. Francis, CLU, ChFC Vice President for Finance & Treasurer Major Walter R. -

Bruce Chapman on RULE and RUIN

Republicanism For the Long Haul "Moderation" is a sentiment, not a disposition -- and it's definitely not a philosophy by Bruce K. Chapman, www.DiscoveryNews.org If there's a better book on the subject of whatever happened to "moderate Republicanism" than Rule and Ruin by Geoffrey Kabaservice (Oxford University Press, January 2012, 482 pages), I can't imagine what it is. And I probably would know, having helped hold aloft the "moderate" banner during the period leading up to Barry Goldwater's nomination in 1964 (see box of links, next page). What Kabaservice has written is thorough, fair, and sometimes very entertaining. That doesn't mean I agree with some of its conclusions. Kabaservice, a writer and former history professor who wrote The Guardians, a widely acclaimed account of Kingman Brewster's reign at Yale, is not happy that the moderate faction in the GOP was slowly, but inexorably, sidelined by more assertive (sometimes aggressive) right‐wingers. "Moderate" once was an accolade. Not any more. Today practically all GOP candidates fall over themselves assuring voters that they are the true conservative in any given race and that their intra‐party rivals are covert moderates or liberals. Rule and Ruin takes advantage of the time that has passed since the moderate vs. conservative battles of the ‘60s and now is yielding archival letters and memos that have not been reported before. They reveal, for example, the true feelings and operations of candidates like Nelson Rockefeller. Governor of New York from 1959 to ’73, “Rocky” was seen as a moderate GOP hero, but in the Kabaservice telling he turns out to believe that extremism in the pursuit of his own career was no vice.