Bearing Witness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

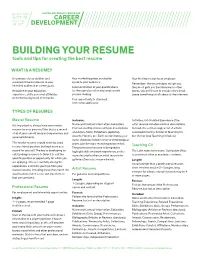

BUILDING YOUR RESUME Tools and Tips for Creating the Best Resume

BUILDING YOUR RESUME tools and tips for creating the best resume WHAT IS A RESUME? • A summary of your abilities and • Your marketing piece, curated to • Your first impression to an employer. accomplishments relevant to your speak to your audience. • Remember: the resume does not get you intended audience or career goals. • A demonstration of your qualifications the job—it gets you the interview. In other • An outline of your education, for the type of position and employment words, you don’t have to include every detail. experience, skills, personal attributes you are seeking. Leave something to talk about at the interview. and other background information. • Your opportunity to stand out from other applicants . TYPES OF RESUMES Master Resume Includes: Activities, Art- Related Experience (The It is important to always have one master Name and Contact Information, Education, artist resume includes minimal descriptions. resume for your personal files that is a record Professional Experience with job descriptions Instead, it is a chronological list of artistic of all of your current and past experiences and and duties, Skills, Exhibitions (optional), accomplishments). Similar to Teaching CV, accomplishments. Awards, Honors, etc. Each section below your but shorter (see Teaching CV below). name should be listed in reverse chronological This master resume should never be used order, with the most recent experience first. Teaching CV for any official position, but kept more as a The professional resume is designed to record for yourself. The key to developing an highlight skills and work experience, so it is The Latin name for resume, Curriculum Vitae, outstanding resume is to tailor it to suit the more descriptive than an artist resume for is used most often in academic contexts. -

Superfine UNSETTLED Pr 10.15.18

t r a n s f o r m e r FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Victoria Reis/Georgie Payne October 15, 2018 202.483.1102 or [email protected] Transformer presents: UNSETTLED - An Afternoon of Performance Art Saturday, November 3, 2018, 3-7pm At Superfine! The Fair Union Market, Dock 5 Event Space 1309 5th Street Northeast, Washington, DC Transformer is pleased to present UNSETTLED – a performance art series curated for Superfine! The Fair by Victoria Reis, Founder and Director of Transformer. UNSETTLED features performances by a select group of leading DC based emerging artists – Hoesy Corona, Rex Delafkaran, Maps Glover, Kunj, and Tsedaye Makonnen – each of whom are pushing performance art forward with their innovative, interdisciplinary work. Previously presented in Miami and New York, with upcoming manifestations in Los Angeles, Superfine! The Fair – created in 2015 by James Miille, an artist, and Alex Mitow, an arts entrepreneur – makes its DC premiere October 31 to November 4, 2018 at Union Market’s Dock 5 event space, featuring 300 visual artists from DC and beyond who will present new contemporary artwork throughout 70+ curated booths. Superfine! also features emerging collector events, tours, film screenings and panels. https://superfine.world/ Always seeking new platforms to connect & promote DC based emerging artists with their peers and supporters, and new opportunities to increase dialogue among audiences about innovative contemporary art practices, Transformer is excited to present UNSETTLED at Superfine! UNSETTLED curator and Executive & Artistic Director of Transformer Victoria Reis states: “Superfine! at Union Market’s Dock 5 presents an opportunity for Transformer to advance our partnership based mission, expand our network, and further engage with a growing new demographic of DC art collectors and contemporary art enthusiasts. -

Get Charmed in Charm City - Baltimore! "…The Coolest City on the East Coast"* Post‐Convention July 14‐17, 2018

CACI’s annual Convention July 8‐14, 2018 Get Charmed in Charm City - Baltimore! "…the Coolest City on the East Coast"* Post‐Convention July 14‐17, 2018 *As published by Travel+Leisure, www.travelandleisure.com, July 26, 2017. Panorama of the Baltimore Harbor Baltimore has 66 National Register Historic Districts and 33 local historic districts. Over 65,000 properties in Baltimore are designated historic buildings in the National Register of Historic Places, more than any other U.S. city. Baltimore - first Catholic Diocese (1789) and Archdiocese (1808) in the United States, with the first Bishop (and Archbishop) John Carroll; the first seminary (1791 – St Mary’s Seminary) and Cathedral (begun in 1806, and now known as the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary - a National Historic Landmark). O! Say can you see… Home of Fort McHenry and the Star Spangled Banner A monumental city - more public statues and monuments per capita than any other city in the country Harborplace – Crabs - National Aquarium – Maryland Science Center – Theater, Arts, Museums Birthplace of Edgar Allan Poe, Babe Ruth – Orioles baseball Our hotel is the Hyatt Regency Baltimore Inner Harbor For exploring Charm City, you couldn’t find a better location than the Hyatt Regency Baltimore Inner Harbor. A stone’s throw from the water, it gets high points for its proximity to the sights, a rooftop pool and spacious rooms. The 14- story glass façade is one of the most eye-catching in the area. The breathtaking lobby has a tilted wall of windows letting in the sunlight. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

2003 Annual Report of the Walters Art Museum

THE YEAR IN REVIEWTHE WALTERS ART MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 France, France, Ms.M.638, folio 23 verso, 1244–1254, The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York Dear Friends: After more than three intense years renovating and reinstalling our Centre Street Building, which con- cluded in June 2002 with the opening of our transformed 19th-century galleries, we stepped back in fiscal year 2002–2003 to refocus attention on our Charles Street Building, with its Renaissance, baroque, and rococo collections, in preparation for its complete reinstallation for a fall 2005 opening. For the Walters, as for cultural institutions nationwide, this was more generally a time of reflection and retrenchment in the wake of lingering uncertainty after the terrorist attack of 9/11, the general economic downturn, and significant loss of public funds. Nevertheless, thanks to Mellon Foundation funding, we were able to make three new mid-level curatorial hires, in the departments of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance and baroque art. Those three endowed positions will have lasting impact on the museum, as will a major addition to our galleries: in September 2002, we opened a comprehensive display of the arts of the ancient Americas, thanks to a long-term loan from the Austen-Stokes Foundation. Now, for the first time, we are able to expand on a collecting area Henry Walters entered nearly a century ago, to match our renowned ancient and medieval holdings in quality and range with more than four millennia of works from the western hemisphere. The 2002–2003 season was marked by three major exhibitions organized by the Walters, and by the continued international tour of a fourth Walters show, Desire and Devotion. -

Historic House Museums

HISTORIC HOUSE MUSEUMS Alabama • Arlington Antebellum Home & Gardens (Birmingham; www.birminghamal.gov/arlington/index.htm) • Bellingrath Gardens and Home (Theodore; www.bellingrath.org) • Gaineswood (Gaineswood; www.preserveala.org/gaineswood.aspx?sm=g_i) • Oakleigh Historic Complex (Mobile; http://hmps.publishpath.com) • Sturdivant Hall (Selma; https://sturdivanthall.com) Alaska • House of Wickersham House (Fairbanks; http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/units/wickrshm.htm) • Oscar Anderson House Museum (Anchorage; www.anchorage.net/museums-culture-heritage-centers/oscar-anderson-house-museum) Arizona • Douglas Family House Museum (Jerome; http://azstateparks.com/parks/jero/index.html) • Muheim Heritage House Museum (Bisbee; www.bisbeemuseum.org/bmmuheim.html) • Rosson House Museum (Phoenix; www.rossonhousemuseum.org/visit/the-rosson-house) • Sanguinetti House Museum (Yuma; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/museums/welcome-to-sanguinetti-house-museum-yuma/) • Sharlot Hall Museum (Prescott; www.sharlot.org) • Sosa-Carrillo-Fremont House Museum (Tucson; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/welcome-to-the-arizona-history-museum-tucson) • Taliesin West (Scottsdale; www.franklloydwright.org/about/taliesinwesttours.html) Arkansas • Allen House (Monticello; http://allenhousetours.com) • Clayton House (Fort Smith; www.claytonhouse.org) • Historic Arkansas Museum - Conway House, Hinderliter House, Noland House, and Woodruff House (Little Rock; www.historicarkansas.org) • McCollum-Chidester House (Camden; www.ouachitacountyhistoricalsociety.org) • Miss Laura’s -

Annual Enforcement & Compliance Report

Maryland Department of the Environment ANNUAL ENFORCEMENT & COMPLIANCE REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2017 Larry Hogan Boyd K. Rutherford Ben Grumbles Horacio Tablada Governor Lieutenant Governor Secretary Deputy Secretary TABLE OF CONTENTS Section One – REPORT BASIS AND SUMMARY INFORMATION 3 Statutory Authority and Scope 4 Organization of the Report 4 MDE Executive Summary 5 MDE Performance Measures – Executive Summary 6 Enforcement Workforce 6 Section 1-301(d) Penalty Summary 7 MDE Performance Measures Historical Annual Summary FY 1998 – 2004 8 MDE Performance Measures Historical Annual Summary FY 2005 – 2010 9 MDE Performance Measures Historical Annual Summary FY 2011 – 2017 10 MDE Enforcement Actions Historical Annual Summary FY 1998 – 2017 11 MDE Penalties Historical Annual Summary Chart FY 1998 - 2017 11 MDE’s Enforcement and Compliance Process and Services to Permittees 12 and Businesses The Enforcement and Compliance Process 12 Enforcement Process Flow Chart 13 Supplemental Environmental Projects (SEPs) 14 Contacts or Consultations with Businesses 15 Compliance Assistance 15 Consultations with Businesses 15 Section Two - ADMINISTRATION DETAILS 17 Measuring Enforcement and Compliance 18 Performance Measures Table Overview and Definitions 19 Enforcement and Compliance Performance Measures Table Format 23 Air and Radiation Administration (ARA) 25 ARA Executive Summary 26 ARA Performance Measures 27 Ambient Air Quality Control 28 Air Quality Complaints 34 Asbestos 38 Radiation Machines 42 Radioactive Materials Licensing and Compliance 46 Land -

The Omegan Voice of the Second District

New York New Jersey Pennsylvania Delaware Maryland The omegan Voice of the Second District InsideInside ThisThis Issue:Issue CorridorErmon VJones MemorialMemoriam Service Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, at West Point 68th Second District Dr. ConferenceJames Bethea $ Million Grant Omegas CBC FatherhoodOmega Men Reception On The Move Omega at Grand OpeningOmega Chapterof National MusemnArticles of African American History and Iota EpsilonCulture Articles Physicians Corner 2013-14 Second DistrictSecond Executive District ShirtsleeveCouncil Conference SuspensionsOpinion/ & ExpulsionsEditorial Section Omega Chapter Articles Grand Basileus Antonio F. Knox, Sr. Grand Basileus AntonioDistrict F.Representative Knox, Sr. Milton Harrison District Representative ShermanDistrict Public L. Charles Relations Zanes E. Cypress, Jr. District Public Relations Zanes E. Cypress, Jr. Fall Edition 2016 Friendship Is Essential To The Soul The Omegan Voice of the Second District The Mighty Second District - Home of 39th Grand Basileus Dr. Andrew A. Ray THE OMEGAN “ Voice of the Second District” EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Milton D. Harrison EDITOR IN CHIEF Zanes E. Cypress, Jr. SENIOR COPY EDITOR Eric “Moby” Brown COPY EDITORS Grand Keeper of Records and Seal James Alexander M. Dante’ Brown Kenneth Rodgers Leroy Finch Demaune A. Millard Rev. Stephen M. Smith Jereleigh A. Archer, Jr. CHIEF PHOTOGRAPHER Jamal Parker STAFF PHOTOGRAPHERS Fitz Devonish Lamonte Tyler PUBLISHING MANAGERS Roy Wesley, Jr. Grand Counselor D. Michael Lyles, Esq. Jeff Spratley The OMEGAN is the Official Organ of the Second District of the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. The Second Dis- trict is comprised of the Great States of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland, It publishes three editions annually, Fall, Winter and Conference Editions, for the Members of the Second District and is widely distributed Internationally throughout all Twelve Districts of the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. -

The Guy's Guide to Baltimore

The Guy's Guide to Baltimore 101 Ways To Be A True Baltimorean! By Christina Breda Antoniades. Edited by Ken Iglehart. Let’s assume, for argument’s sake, that you’ve mastered the Baltimore lexicon. You know that “far trucks” put out “fars” and that a “bulled aig” is something you eat. You know the best places to park for O’s games, where the speed traps are on I-83, and which streets have synchronized traffic lights. You know how to shell a steamed crab. You never, EVER attempt to go downy ocean on a Friday evening in the dead of summer. And, let’s face it, you get a little upset when your friends from D.C. call you a Baltimoro… well, you know. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Do you really know all it takes to be a true Baltimorean? ¶ Here, we’ve compiled a list of the 101 activities, quirky habits, and oddball pastimes, that, even if you only did half of them, would earn you certification as a true Baltimorean. Some have stood the test of time, some are new favorites, but all are unique to Charm City. If you’re a grizzled native, you’ll probably find our list a fun test that takes you down memory lane. And if you’re new in town, the guide below will definitely help you to pass yourself off as a local. ¶ So, whether you’ve been here 60 days or 60 years, we’re sure you’ll find something new (or long forgotten) in the pages that follow. -

PAUL DANIEL 1623 Bolton Street, Baltimore, MD 21217 Cell: 443-691-9764 Email: [email protected]

PAUL DANIEL 1623 Bolton Street, Baltimore, MD 21217 Cell: 443-691-9764 email: [email protected] https://bakerartist.org/node/921 SELECTED PUBLIC ART: 2019 Art on the Waterfront commission, Middle Branch Park, Balt Office of Promotion & the Arts 2015 Finalist for Art-in-Transit, Redline, Mass Transit Administration Finalist for Art-in-Transit, Purple Line, Mass Transit Administration 2014-15 Manolis, Cylburn Arboretum 2013 Finalist Unity Parkside Public Art, DC Commission on the Arts & Humanities 2009-’16 Flirting with Memory on exhibition at Johns Hopkins BayvieW Hospital, Baltimore, MD 2007-’16 Kiko-Cy on exhibit for the Baltimore Office of Promotion and Tourism, St Paul St median 1997 Oak Leaf Gazebo, Mitchellville, MD, Collaboration With artist Linda DePalma; Rocky Gorge Communities Commission 1992 Naiad's Pool, Rockcrest Ballet Center & Park, Rockville, MD; Art in Public Places 1991 Double Gamut, Franklin Street Parking Garage, Baltimore, MD, Baltimore 1% for Art Jack Tar’s Fancy, Snug Harbor Cultural Center, Staten Island, NY, Collaboration With artist Linda DePalma; Curator: Olivia Georgia 1990 Sun Arbor & Moon Arbor, Quiet Waters Park, Annapolis, MD Collaboration With artist Linda DePalma; Anne Arundel Co. Dept. of Parks & Recreation; Art Consultant: Cindy Kelly 1987 Goal Keeper, William Myers Pavilion, Brooklyn, MD; Baltimore 1% for Art Program 1985 Messenger, Clifton T. Perkins Hospital, Jessup, MD; MD State Fine Art in Public Places 1984 Venter, State Center Metro Station, Baltimore, MD; Mass Transit Administration 1978 Titan, Liberty Elementary School, Baltimore, MD; Baltimore 1% for Art Program ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS: 2018 Acknowledging the Wind: Kinetic SculPtures by Paul Daniel, LadeW Topiary Gardens, Monkton, MD 2015 On & Off the Wall: 3D & 2D work by Paul Daniel, Project 1628, Baltimore, MD 2009 Paul Daniel-Current Reflection, Katzen Art Museum, American University, DC 2010 2000 Paul Daniel- Kinetic SculPtures in the Pond, The Park School, Brooklandville, MD 1990 Paul Daniel- Recent SculPture, C. -

Maryland Historical Magazine Patricia Dockman Anderson, Editor Matthew Hetrick, Associate Editor Christopher T

Winter 2014 MARYLAND Ma Keeping the Faith: The Catholic Context and Content of ry la Justus Engelhardt Kühn’s Portrait of Eleanor Darnall, ca. 1710 nd Historical Magazine by Elisabeth L. Roark Hi st or James Madison, the War of 1812, and the Paradox of a ic al Republican Presidency Ma by Jeff Broadwater gazine Garitee v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore: A Gilded Age Debate on the Role and Limits of Local Government by James Risk and Kevin Attridge Research Notes & Maryland Miscellany Old Defenders: The Intermediate Men, by James H. Neill and Oleg Panczenko Index to Volume 109 Vo l. 109, No . 4, Wi nt er 2014 The Journal of the Maryland Historical Society Friends of the Press of the Maryland Historical Society The Maryland Historical Society continues its commitment to publish the finest new work in Maryland history. Next year, 2015, marks ten years since the Publications Committee, with the advice and support of the development staff, launched the Friends of the Press, an effort dedicated to raising money to be used solely for bringing new titles into print. The society is particularly grateful to H. Thomas Howell, past committee chair, for his unwavering support of our work and for his exemplary generosity. The committee is pleased to announce two new titles funded through the Friends of the Press. Rebecca Seib and Helen C. Rountree’s forthcoming Indians of Southern Maryland, offers a highly readable account of the culture and history of Maryland’s native people, from prehistory to the early twenty-first century. The authors, both cultural anthropologists with training in history, have written an objective, reliable source for the general public, modern Maryland Indians, schoolteachers, and scholars. -

Art Seminar Group 1/29/2019 REVISION

Art Seminar Group 1/29/2019 REVISION Please retain for your records WINTER • JANUARY – APRIL 2019 Tuesday, January 8, 2019 GUESTS WELCOME 1:30 pm Central Presbyterian Church (7308 York Road, Towson) How A Religious Rivalry From Five Centuries Ago Can Help Us Understand Today’s Fractured World Michael Massing, author and contributor to The New York Review of Books Erasmus of Rotterdam was the leading humanist of the early 16th century; Martin Luther was a tormented friar whose religious rebellion gave rise to Protestantism. Initially allied in their efforts to reform the Catholic Church, the two had a bitter falling out over such key matters as works and faith, conduct and creed, free will and predestination. Erasmus embraced pluralism, tolerance, brotherhood, and a form of the Social Gospel rooted in the performance of Christ-like acts; Luther stressed God’s omnipotence and Christ’s divinity and saw the Bible as the Word of God, which had to be accepted and preached, even if it meant throwing the world into turmoil. Their rivalry represented a fault line in Western thinking - between the Renaissance and the Reformation; humanism and evangelicalism - that remains a powerful force in the world today. $15 door fee for guests and subscribers Tuesday, January 15, 2019 GUESTS WELCOME 1:30 pm Central Presbyterian Church (7308 York Road, Towson) Le Jazz Hot: French Art Deco Bonita Billman, instructor in Art History, Georgetown University What is Art Deco? The early 20th-century impulse to create “modern” design objects and environments suited to a fast- paced, industrialized world led to the development of countless expressions, all of which fall under the rubric of Art Deco.