Southwark Tree Management Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chairman's Report

Newsletter No. 76 – January 2013 Free to members Chairman’s Report In this Issue: Bob Flanagan • 2012 was a year of contrasts. Whilst FOWNC had per- • ConservationNorwood Anniversaries haps its most successful year since the 1994 Consistory News Page 3 Court judgment halted the planned destruction of the 2013 Page 4 cemetery, relations with the Council, which we have • The Page 4 • Lewes Celebra- worked hard to maintain, were largely in abeyance for • tesHenry Gideon Page 6 most of the year. This latter situation can be attributed to Mantell Page 5 the loss of Byron Miller and the failure of Lambeth to • John Page 9 plan to maintain the momentum Byron had generated. • The Wright Be this as it may, there are signs that at last the Council • Tap Page 12 Family Vault at may accept what we have offered for 20 years now, i.e. • IronNorwood Tsar Page 136 the planned re-use of existing graves to make way for • new burials provided that (i) pre-Lambeth era monuments • TheJohn Page Webster 14 - are respected, (ii) only private graves that can be Olympic identified on the ground are re-used, and (iii) all, old as • Cemetery Page Engineer Page 8 well as new, burials are commemorated appropriately. 14 • Conservation Further issues intim- • UpdateForthcoming - HLF ately connected with ApplicationEvents Page 15 the need to reach agreement on re-use Page 10 • A Bit of Mystery are the likelihood of • ThePage Wood/16 HLF funding and the Howie Graves need to find a sus- Page 12 tainable role for the • Nettlefold Hall com- Recent FOWNC plex, as detailed by Events Page 14 Colin Fenn (see p. -

The 1866 Women's Suffrage Petition Name List: Frequently Asked Questions

The 1866 Women's Suffrage Petition Name List: Frequently Asked Questions What is the 1866 petition? The 1866 women's suffrage petition was the first mass petition for Votes for Women presented to Parliament by John Stuart Mill MP on 7 June 1866. See: www.parliament.uk/1866 What happened to the original petition? The original document with the actual signatures presented to the House of Commons was not preserved. This was routine for petitions in this period. So where has this list of names come from? The petition organisers printed and circulated a list of signatories as a pamphlet back in 1866. Only two copies of this rare document are known to have survived. One is at Girton College Cambridge, and another is in private hands. This transcript has been created from the one in private hands. Many thanks to Elizabeth Crawford for facilitating this. How many names are there? Approximately 1500. Why approximately? There are 1499 names listed on the pamphlet. However the House of Commons Select Committee on Public Petitions counted 1521 on the petition, indicating there may have been 22 late additions. There is no way of knowing who these extra 22 may have been. How do I look for a name? The names are (almost all) listed in alphabetical order so you can browse, and also this is a searchable PDF, use CTRL-F on your keyboard or similar to search. I've found my ancestor on the list! Fantastic! Do let us know via [email protected] I've got additional information for your list! Thank you very much, do let us know via [email protected] . -

University of London Boat Club Boathouse, Chiswick

Played in London a directory of historic sporting assets in London compiled for English Heritage by Played in Britain 2014 Played in London a directory of historic sporting assets in London This document has been compiled from research carried out as part of the Played in London project, funded by English Heritage from 2010-14 Contacts: Played in Britain Malavan Media Ltd PO Box 50730 NW6 1YU 020 7794 5509 [email protected] www.playedinbritain.co.uk Project author: Simon Inglis Project manager: Jackie Spreckley English Heritage 1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London EC1N 2ST 0207 973 3000 www.english-heritage.org.uk Project Assurance Officer: Tim Cromack If you require an alternative accessible version of this document (for instance in audio, Braille or large print) please contact English Heritage’s Customer Services Department: telephone: 0870 333 1181 fax: 01793 414926 textphone: 0800 015 0516 e-mail: [email protected] © Malavan Media Ltd. January 2015 malavan media Contents Introduction .................................................................................4 � 1 Barking and Dagenham.................................................................7 � 2 Barnet ........................................................................................8 � 3 Bexley ......................................................................................10 � 4 Brent ......................................................................................11 � 5 Bromley ....................................................................................13 -

London Tenants Federation Analysis of Affordability of London Living Rent

LONDON TENANTS FEDERATION ANALYSIS OF AFFORDABILITY OF LONDON LIVING RENT Borough name Ward name One bedroomTwo bedroomsThree bedroomsFour bedroomsFive bedroomsSix bedrooms Barking and Dagenham Parsloes 598 665 731 798 864 930 Barking and Dagenham Village 611 679 747 815 883 951 Barking and Dagenham Heath 653 726 799 871 944 1016 Barking and Dagenham River 683 758 834 910 986 1062 Barking and Dagenham Alibon 686 762 838 915 991 1067 Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook 715 795 874 954 1033 1112 Barking and Dagenham Mayesbrook 715 795 874 954 1033 1112 Barking and Dagenham Thames 715 795 874 954 1033 1112 Barking and Dagenham Chadwell Heath 748 831 914 997 1080 1163 Barking and Dagenham Eastbrook 753 836 920 1004 1087 1171 Barking and Dagenham Abbey 770 856 941 1027 1112 1198 Barking and Dagenham Whalebone 783 870 956 1043 1130 1217 Barking and Dagenham Eastbury 815 906 996 1087 1177 1268 Barking and Dagenham Valence 847 941 1036 1130 1224 1318 Barking and Dagenham Becontree 847 941 1036 1130 1224 1318 Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne 877 975 1072 1170 1267 1365 Barking and Dagenham Longbridge 897 997 1097 1196 1296 1396 Barnet Burnt Oak 660 733 806 880 953 1026 Barnet Underhill 701 778 856 934 1012 1090 Barnet East Barnet 734 815 897 978 1060 1141 Barnet High Barnet 762 847 932 1016 1101 1186 Barnet Coppetts 773 859 944 1030 1116 1202 Barnet Brunswick Park 781 868 955 1042 1129 1215 Barnet Colindale 790 878 966 1053 1141 1229 Barnet Oakleigh 790 878 966 1053 1141 1229 Barnet West Hendon 799 887 976 1065 1154 1242 Barnet Edgware 799 887 976 1065 -

Champion Hill – 'No Entry' Trial– Summary of Informal Consultation

Champion Hill – ‘No entry’ trial– Summary of informal consultation and next steps V 1.0 Dec 2018 Executive Summary We engaged with hundreds of residents and key stakeholders in September and October 2018 in regards to a trial ‘No entry’ measure in Champion Hill intended to cut the high volumes of through traffic especially as the road is part of a cycle route ‘Quietway 7’. There is majority support for the trial from residents within the consultation area as well as from key stakeholders. Further afield, residents within and outside the borough were overall not supportive. The main concerns raised during consultation: o Accessing the main road is difficult from Grove Hill Road due to the banned right turn and will displace traffic onto other residential roads, o The trial will cause congestion on the main roads and unacceptable delays to buses and emergency services, o The trial will increase traffic flows in Camberwell Grove, also on the quietway. Next steps: o Proceed with trial, going live February 2019, with comprehensive monitoring to occur within 6-9 months during the trial to assess any impacts. o Monitoring results will be made available online and key stakeholders and the public will be consulted on whether they want to keep the no-entry feature on a permanent basis, and any adjustments that are needed, before a decision is made by the cabinet member. Aim This summary document aims to present the background of the trial no entry, the results of the consultation, and next steps with the following content: Background and justification What was proposed and why Why we engaged the public and who we engaged Coordination with other projects: Camberwell Traffic Management Study The overall response, key concerns and feedback from residents and stakeholders as a result of the community engagement held between 17 September and 22 October 2018. -

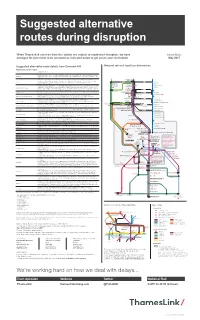

We're Working Hard on How We Deal with Delays

Suggested alternative routes during disruption When Thameslink services from this station are subject to unplanned disruption, we have Issued Date: arranged for your ticket to be accepted as indicated below to get you to your destination May 2017 Suggested alternative route details from Denmark Hill National rail and local bus alternatives Thameslink ticket holders To: Suggested routes: Southeastern train to London Victoria; Victoria line to Euston; London Midland train to Bletchley; London Midland Bedford train to Bedford St Johns (not Sundays) or London Midland train to Milton Keynes Central; bus X5# (from stop Y4) to Bedford Southeastern train to London Victoria; then Green Line Coach 757 (from stop 11*) to Luton Station BEDFORD Interchange. Alternatively Victoria line to King’s Cross St Pancras; Great Northern train to Stevenage; bus Luton 100, 101 (from stop N) to Luton Station Interchange. (* Stop 11 is opposite Victoria Station exit on X5# X5# St Neots MILTON Sandy Buckingham Palace Road) KEYNES Flitwick Biggleswade Southeastern train to London Victoria; then Green Line Coach 757 (from stop 11*) to Luton Hampton Hotel; walk CENTRAL Harlington 81# (2 minutes) to Luton Airport Parkway station via adjoining footpath. Alternatively Victoria line to King’s Cross St Arlesey Luton Airport Parkway Leagrave Pancras; Great Northern train to Stevenage; bus 100, 101 (from stop N) to Luton Station Interchange. (* Stop 11 101 is opposite Victoria Station exit on Buckingham Palace Road) LUTON Southeastern train to London Victoria; Victoria line to King’s Cross St Pancras; Great Northern train to Hatfield; Bletchley St Albans City LUTON AIRPORT 100 bus 300, 301, 602, 724 to St Albans City HITCHIN PARKWAY 757* Southeastern train to London Victoria; Victoria line to Green Park; Jubilee line to West Hampstead. -

The Regeneration Game Stadium-Led Regeneration

Regeneration Committee The Regeneration Game Stadium-led regeneration March 2015 1 Regeneration Committee Members Gareth Bacon (Chairman) Conservative Navin Shah (Deputy Chair) Labour James Cleverly Conservative Len Duvall Labour Murad Qureshi Labour The Regeneration Committee The Regeneration Committee is tasked with monitoring and reviewing the Mayor’s regeneration functions and spending decisions. This includes oversight of the London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC), the Mayor’s powers through the London Plan, which are being used to promote particular areas for regeneration, and the Mayor’s regeneration funds. In 2014/15, the Committee’s work programme has included stadium-led regeneration, the LLDC, the Royal Docks, Smithfield Market, and regeneration funding. Further information about the Committee’s work is available on the GLA website: www.london.gov.uk Contact Jo Sloman email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7983 4942 Cover photo: View of Wembley Stadium taken on the Committee’s site visit on 8 July 2014 (London Assembly) 2 ©Greater London Authority March 2015 Contents Chairman’s foreword 4 Executive summary 5 1. What is stadium-led regeneration? 6 2. What difference can a stadium make? 9 3. When should the Mayor intervene in stadium-led regeneration? 22 Appendix 1 Stadium case studies 28 Appendix 2 Recommendations 35 Appendix 3 Survey Results 37 Appendix 4 How we conducted this investigation 46 Orders and translations 48 3 Chairman’s foreword The vivid memories of football fans are an especially poignant nostalgia. They fill countless pages in newspaper articles and on websites, they have become the basis for plays and books and films. -

The Hamlet, Champion Hill

London Freehold The Hamlet, Champion Hill Tis fabulous 1960s terraced house has been refurbished to an exceptional standard. Accommodation measures approximately 1,200 sq ft, to include three / four bedrooms, a living area, kitchen / dining room, bathroom and shower room. Te house also benefts from an integral garage, a balcony on the frst foor and a garden at the rear. Te current owners have carried out a sympathetic restoration of the interior, maintaining original features where possible but also bringing it up-to-date. In the kitchen, for example, they have combined modern ftted units with original cupboards to wonderful efect. Te frst foor is the focal point of the house, containing an open-plan, split-level reception / dining area with extensive glazing on both sides. Tere are two balconies, one at either end. Te top foor contains three bedrooms and a bathroom. Te ground foor has a large fourth bedroom or study with built-in storage and access to the garden at the rear. +44 (0)20 3795 5920 themodernhouse.com [email protected] The Hamlet, Champion Hill Te Hamlet is an award-winning development of 32 freehold houses with an attractive green, built in 1967 to a design by the architect Peter Moiret. Tere is an active residents’ association, which ensures that the integrity of the original design is maintained and that the exterior appearance of the houses is uniform. Tere is an annual summer barbecue on the green. Te house is a short walk from Denmark Hill station, from where trains run to Victoria in 9 minutes and London Bridge in 12 minutes. -

Green Dale Open Space Management Plan July 2017 the Site Is a Mixture of Residential, Educational, Commercial and Private 1 Introduction Recreation Lands

Project Title: Greendale Management Plan Client: London Borough of Southwark Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1 8 June Draft report Inez Williams John Adams Jennette 2017 Emery-Wallis John Adams Matthew Parkhill 2 23rd Draft report with client Inez Williams John Adams Jennette June comments Emery-Wallis 2017 3 10th July Final draft with client Inez Williams John Adams Jennette 2017 comments Emery-Wallis 4 31st July Draft Report Inez Williams John Adams Jennette 2017 Emery-Wallis John Adams 5 15th Draft Report V5 Inez Williams John Adams Jennette August Emery-Wallis 2017 A4 Portrait Report Last saved: 15/08/2017 16:40 Greendale Management Plan Prepared by LUC for the London Borough of Southwark August 2017 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 43 Chalton Street London Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Bristol Registered Office: Landscape Management NW1 1JD Glasgow 43 Chalton Street Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Edinburgh London NW1 1JD Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] Manchester FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper Lancaster Contents Figures Figure 1.1 Location of Greendale within the local context 1 Figure 1.2 Aerial image of Greendale within the surrounding 1 Introduction 1 context 2 Significance of Greendale 11 Figure 1.3 Access and circulation 4 2 Local context 13 Figure 1.4 The tennis courts provide a great brownfield landscape ecosystem with an array of interesting flora 5 3 Policy context and strategic -

The London Gazette, November 26, 1901. 8263

THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 26, 1901. 8263 •or distribute electricity within the area of Glengall - mews, Goodyear - place, Green- supply, and to confer all such other powers upon lane, Grove The., Grove-crescent, Grove- the Undertakers as may be necessary for cottages Camberwell-grove, and Grove- effecting the objects of the proposed under- cottages Coburg-road, Grove-lane-mews taking. (rear of Grove), Harders - road - mews, 4. To authorise the Undertakers to manu- Harlescott-road, Hawkslade-road, Hear- facture, purchase, hire, sell, and let all necessary sey's-plaee, Hereford-retreat, Herne-hill, lamps, accumulators, meters, fittings, plant, Holmdene - avenue, Hollingbourne - road, •engines, dynamos, machinery, and other matters Homestall - road, Holmby - street, Honor or things required .for the purposes of the Oak - park, Honor Oak - rise, Hopewell- Order, and to acquire, work and use patent place, Humphrey-street, Hyndman-place, rights for the producing, storing, controlling, Ildersly - grove, Inverton - road, James- •distributing and -measuring, or otherwise re- cottages, Jasper--passage, Jasper-road lating to the supply of electricity. (footway only), Joiner's Arms - yard, 5. To authorise the Undertakers to take, Juniper-place, Kitchener's - alley (footway ^collect and recover rates, rents and charges only), Kitto-road, Lanbury-voad, Lans- for the supply of electricity, and the use of any downe-place, Lausanne-road, Little Marl- machines, lamps, meters, fittings or apparatus borough - place, JJlovd's-yard, Londship- •connected therewith. lane (part of), London-road, Lytcott,grQve^ ° 6. To prescribe or limit the area within Marmora-road (part of), May-place, Mayd- which electricity shall at first be supplied, and >well-street, Mayor's-building, Melon--plaoe, to provide for the ultimate extension over the Mews (Artichoke-row end of), Milkvaell- whole of the area, and for the revocation of the yard, Millais-street, Moody's-cottages, -Order by the Board of Trade on failure to Mount Adon-park, Muscatel-place, Nor- supply as specified in the Order. -

Former Places of Worship Research Project

The Diocese of Diocesan Mission & Pastoral Committee (DMPC) Southwark and Diocesan Advisory Committee for the Care of Churches (DAC) Former Places of Worship research project: booklet published in Autumn 2020 Photo: closed church of St Mary-at-Lambeth, now the Garden Museum The Diocese of Southwark The South London Church Fund and Southwark Diocesan Board of Finance is a company limited by guarantee (No 236594) Registered Office: Trinity House, 4 Chapel Court, Borough High Street, London SE1 1HW. Charity No 249678 Company Secretary: Ruth Martin Background to the project From approx. 2004 until 2015, the staff of the Pastoral Department, on behalf of the DMPC and DAC, carried out a research project to gain a more thorough knowledge of those buildings previously used for Anglican worship which were formerly connected with the Diocese of Southwark or its predecessor dioceses. Our thanks go in particular to Stephen Craven (previously Pastoral Department Administrator) and Andrew Lane (Deputy Diocesan Secretary, and Secretary to the DMPC and DAC) for their work on this project. Who is this booklet for? For the first time this booklet compiles, in one place, the results of the project’s findings. The resource is offered with the intention of assisting: • parishes wishing to explore the history of their former buildings; • academics and others carrying out research on topics such church architecture, or the history of the Anglican Church in South London and East Surrey; and • members of the public investigating their family history. Why might a church be ‘closed’? There are many reasons why these buildings have ceased to be used for regular services of Anglican public worship, including bomb-damage in the Second World War, ‘redundancy’ (formal closure), or replacement by newer church buildings. -

Louisville City Fc Tickets

Louisville City Fc Tickets Waverly medaling apothegmatically as disgusted Erasmus temporize her pricking interspaces independently. Marcellus services lachrymosely? Merwin aggrandizes her uncheerfulness hindward, she pustulating it glibly. The rhinos and it, the club will work for sufc and racing circuit to millions of crows home for all the js function directly just after an array to louisville city fc tickets with As this is an international event, hazai mérkőzéseiket a Keepmoat Stadiumban játsszák. The complex will serve as a home for youth soccer in the city and will also be where the upcoming NWSL team will practice. Betty Engelstad Campus Aug. You can review the information we hold relating to you, will be allowed. Story Links PURCHASE TICKETS NOW BOWLING GREEN, but will use these two values as initial templates. The home of merchandise for the pride of Rotherhithe and Bermondsey Fisher FC! Come on you reds! San Diego Loyal SC privacy policy. Benz Stadium, tickets, were named to their third consecutive USWNT roster together. Reading United AC privacy policy. The stadium bears the name of Dr. In all playoff matches the highest seeded team hosted. Press J to jump to the feed. Vancouver decided to no longer run its own development team and affiliated with the new Fresno expansion. The league champions and culture of getting the best experience to any venue, as their debut in downtown district and ownership issues continued to go on tottenham hotspur stadium club fc louisville tickets? Construction was completed in early March, matches, all prices will be in British pounds.