Thesis at Cambridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wish You All a Very Happy Diwali Page 2

Hindu Samaj Temple of Minnesota Oct, 2012 President’s Note Dear Community Members, Namaste! Deepavali Greetings to You and Your Family! I am very happy to see that Samarpan, the Hindu Samaj Temple and Cultural Center’s Newslet- ter/magazine is being revived. Samarpan will help facilitate the accomplishment of the Temple and Cultural Center’s stated threefold goals: a) To enhance knowledge of Hindu Religion and Indian Cul- ture. b) To make the practice of Hindu Religion and Culture accessible to all in the community. c) To advance the appreciation of Indian culture in the larger community. We thank the team for taking up this important initiative and wish them and the magazine the Very Best! The coming year promises to be an exciting one for the Temple. We look forward to greater and expand- ed religious and cultural activities and most importantly, the prospect of buying land for building a for- mal Hindu Temple! Yes, we are very close to signing a purchase agreement with Bank to purchase ~8 acres of land in NE Rochester! It has required time, patience and perseverance, but we strongly believe it will be well worth the wait. As soon as we have the made the purchase we will call a meeting of the community to discuss our vision for future and how we can collectively get there. We would greatly welcome your feedback. So stay tuned… Best wishes for the festive season! Sincerely, Suresh Chari President, Hindu Samaj Temple Wish you all a Very Happy Diwali Page 2 Editor’s Note By Rajani Sohni Welcome back to all our readers! After a long hiatus, we are bringing Samarpan back to life. -

Guru Tegh Bahadur

Second Edition: Revised and updated with Gurbani of Guru Tegh Bahadur. GURU TEGH BAHADUR (1621-1675) The True Story Gurmukh Singh OBE (UK) Published by: Author’s note: This Digital Edition is available to Gurdwaras and Sikh organisations for publication with own cover design and introductory messages. Contact author for permission: Gurmukh Singh OBE E-mail: [email protected] Second edition © 2021 Gurmukh Singh © 2021 Gurmukh Singh All rights reserved by the author. Except for quotations with acknowledgement, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or medium without the specific written permission of the author or his legal representatives. The account which follows is that of Guru Tegh Bahadur, Nanak IX. His martyrdom was a momentous and unique event. Never in the annals of human history had the leader of one religion given his life for the religious freedom of others. Tegh Bahadur’s deed [martyrdom] was unique (Guru Gobind Singh, Bachittar Natak.) A martyrdom to stabilize the world (Bhai Gurdas Singh (II) Vaar 41 Pauri 23) ***** First edition: April 2017 Second edition: May 2021 Revised and updated with interpretation of the main themes of Guru Tegh Bahadur’s Gurbani. References to other religions in this book: Sikhi (Sikhism) respects all religious paths to the One Creator Being of all. Guru Nanak used the same lens of Truthful Conduct and egalitarian human values to judge all religions as practised while showing the right way to all in a spirit of Sarbatt da Bhala (wellbeing of all). His teachings were accepted by most good followers of the main religions of his time who understood the essence of religion, while others opposed. -

Subversion of the Cult of True Womanood in Kate

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Hrvatskog jezika i književnosti Studentica: Matea Srčnik Subversion of the Cult of True Womanood in Kate Chopin's novel The Awakening and Charlotte Perkins Gilman's short story „The Yellow Wallpaper“ (Subverzija kulta pravog ženstva u romanu Buđenje Kate Chopin i pripovjetci „Žuta tapeta“ Charlotte Perkins Gilman) Završni rad Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Biljana Oklopčić Osijek, 2011. Summary The paper explains what the Cult of True Womanhood is and how it manifested itself in the period of its strongest influence, the nineteenth century. It goes on to explain how it degraded women, and how certain Victorian writers saw it fit to deny virtues it expected of women by means of their literary work. Subversion of this Cult is observed on two works by two authors; Kate Chopin and her novel The Awakening, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman and her short story „The Yellow Wallpaper“. On various examples and quotations, it explains how the authors rebelled against the norm forced upon women by Victorian society. The paper concludes these two literary efforts to be the cornerstone of future feminist literature. Key words: subversion, true womanhood, oppression, Kate Chopin, Charlotte Perkins Gilman Contents: Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 -

2015 Kiddieland

STATE FAIR MEADOWLANDS RIDE LIST - 2015 KIDDIELAND Description Height Requirements Description Height Requirements Banzai 52" MIN Bumble Bee 36" MIN W/O ADULT, 32" MIN W ADULT Bumper Boats - Water 52" MIN W/O ADULT, 32" MIN W ADULT Frog Hopper 56" MAX, 36" MIN-NO ADULTS Bumper Cars 48" MIN TO DRIVE, 42" MIN TO RIDE Speedway 56" MAX, 36" MIN-NO ADULTS Cliffhanger 46" MIN Go Gator 54" MAX, 42" MIN-NO ADULTS Crazy Mouse 55" MIN W/O ADULT, 45" MIN W ADULT Jet Ski/Waverunner 54" MAX, 36" MIN-NO ADULTS Crazy Outback 42" MIN ALONE, 36" MIN W/ADULT Motorcycles 54" MAX, 36" MIN-NO ADULTS Cuckoo Fun House 42" MIN ALONE, 36" MIN W/ADULT Quadrunners 54" MAX, 30" MIN-NO ADULTS Darton Slide TBD VW Cars 54" MAX, 30" MIN-NO ADULTS Disko TBD Double Decker Carousel 52" MIN UABA Enterprise ENTERPRISE 52" MINIMUM Mini Bumper Boats - Water 52" MAX-NO ADULTS Fireball 50" MIN Merry-Go-Round 42" MIN W/O ADULT, NO MIN W ADULT Giant Wheel 54" MIN W/O ADULT, NO MIN W ADULT Rockin' Tug 42" MIN W/O ADULT, 36" MIN W ADULT Gravitron 48" MIN Wacky Worm 42" MIN W/O ADULT, 36" MIN W ADULT Haunted House Dark Ride 42" MIN ALONE, 36" MIN W/ADULT Fire Chief 42" MIN UABA Haunted Mansion Dark Ride 42" MIN ALONE, 36" MIN W/ADULT Family Swinger 42" MIN OUTER SEAT, 36" MIN INNER Haunted Mansion Dark Ride 42" MIN ALONE, 36" MIN W/ADULT Happy Swing 42" MIN OUTER SEAT, 36" MIN INNER Heavy Haulin' Inflate 32" MIN, 76" MAX; 250 LBS MAX Jungle of Fun 42" MIN Himalaya 42” Min. -

Crs4e1forkaytee

Season 4, Episode 1: Unexpected Emotions + How We Spent Our Break Mon, 8/2 • 49:22 Meredith Monday Schwartz 00:10 Hey readers, welcome to the Currently Reading podcast. We are bookish best friends who spend time every week talking about the books that we read recently. And as you know, we don't shy away from having strong opinions. So get ready. Kaytee Cobb 00:25 We are light on the chitchat, heavy on the book talk, and our descriptions will always be spoiler free. We'll discuss our current reads, a bookish deep dive, and then we'll press books into your hands. Meredith Monday Schwartz 00:35 I'm Meredith Monday Schwartz, a mom of four and full time CEO living in Austin, Texas. And talking about books is such a joy in my life. Kaytee Cobb 00:43 And I'm Kaytee Cobb, a homeschooling mom of four living in New Mexico. And I am excited for a new season. This is episode number one of season four and we are so glad you're here. Season Four, Meredith, Meredith Monday Schwartz 00:57 I can't believe it. We're here. Kaytee Cobb 00:59 We're here for season four. Meredith Monday Schwartz 01:01 I know. I know. It sounds like such big girls, right? season four, it's some big girl. Kaytee Cobb 01:06 We're like four year olds now almost like that's crazy. Meredith Monday Schwartz 01:11 I know. And boy, I was not lying when I said the break that we've just had, has reminded me how much I love talking about books. -

Constructing Womanhood: the Influence of Conduct Books On

CONSTRUCTING WOMANHOOD: THE INFLUENCE OF CONDUCT BOOKS ON GENDER PERFORMANCE AND IDEOLOGY OF WOMANHOOD IN AMERICAN WOMEN’S NOVELS, 1865-1914 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Colleen Thorndike May 2015 Copyright All rights reserved Dissertation written by Colleen Thorndike B.A., Francis Marion University, 2002 M.A., University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 2004 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Wesley Raabe, Associate Professor, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Babacar M’Baye, Associate Professor, Department of English Stephane Booth, Associate Provost Emeritus, Department of History Kathryn A. Kerns, Professor, Department of Psychology Accepted by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English James L. Blank, Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Conduct Books ............................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 2 : Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and Advice for Girls .......................................... 41 Chapter 3: Bands of Women: -

Devotional Practices (Part -1)

Devotional Practices (Part -1) Hare Krishna Sunday School International Society for Krishna Consciousness Founder Acarya : His Divine Grace AC. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Price : $4 Name _ Class _ Devotional Practices ( Part - 1) Compiled By : Tapasvini devi dasi Vasantaranjani devi dasi Vishnu das Art Work By: Mahahari das & Jay Baldeva das Hare Krishna Sunday School , , ,-:: . :', . • '> ,'';- ',' "j",.v'. "'.~~ " ""'... ,. A." \'" , ."" ~ .. This book is dedicated to His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder acarya ofthe Hare Krishna Movement. He taught /IS how to perform pure devotional service unto the lotus feet of Sri Sri Radha & Krishna. Contents Lesson Page No. l. Chanting Hare Krishna 1 2. Wearing Tilak 13 3. Vaisnava Dress and Appearance 28 4. Deity Worship 32 5. Offering Arati 41 6. Offering Obeisances 46 Lesson 1 Chanting Hare Krishna A. Introduction Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu, an incarnation ofKrishna who appeared 500 years ago, taught the easiest method for self-realization - chanting the Hare Krishna Maha-mantra. Hare Krishna Hare Krishna '. Krishna Krishna Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rams Rams Rama Hare Hare if' ,. These sixteen words make up the Maha-mantra. Maha means "great." Mantra means "a sound vibration that relieves the mind of all anxieties". We chant this mantra every day, but why? B. Chanting is the recommended process for this age. As you know, there are four different ages: Satya-yuga, Treta-yuga, Dvapara-yuga and Kali-yuga. People in Satya yuga lived for almost 100,000 years whereas in Kali-yuga they live for 100 years at best. In each age there is a different process for self realization or understanding God . -

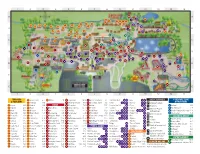

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 a B C D E F G a B C D E F G 1 2 3 4

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 A 44 A 23 37 G 28 35 36 32 31 30 29 14 16 34 33 12 22 24 1 3 4 10 11 2 5 6 13 15 43 21 9 B G B 20 7 8 17 18 3 19 4 24 27 5 6 19 25 20 21 7 C 25 C 22 23 6 12 3 4 2 45 1 2 18 28 3 6 13 16 19 30 1 G 7 17 23 2 15 31 D 2 20 25 27 D 10 29 32 3 G G G 21 G 26 5 1 8 4 12 1 33 G 34 G 1 5 G 24 G 14 1 6 G 9 22 G 13 G G 18 11 11 42 G 5 G G 8 E 4 10 35 E 9 15 G 7 40 41 16 36 14 2 G 4 F 37 F 3 39 17 38 G G 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 TERRACES 21 Group Foods 4-C 16 Willow 7-B 43 Log Flume 10-B 11 Space Scrambler 3-E Cinnamon Roll 9 21 Milk 2 9 GUEST SERVICES X-VENTURE ZONE & PAVILIONS ATTRACTIONS 34 Irontown 9-B 24 Merry-Go-Round 9-D 23 Speedway Junior 9-D Coffee 2 9 19 Nachos 10 25 Drinking Fountain 13 Aspen 6-B 12 Juniper 6-B RIDES 18 Moonraker 7-D 39 Spider 11-F Corn on the Cob 22 Pizza 4 10 Telephone 1 Catapult 2-D 9 Bighorn 4-B Maple 6-C 25 Baby Boats 9-D 36 Musik Express 14-E 22 Terroride 7-E Corndog 10 15 Popcorn 7 Strollers, Wagons 2 Top Eliminator 2-F 15 Birch 6-B 22 Meadow 3-C 12 Bat 4-C 13 OdySea 5-C 31 Tidal Wave 10-D Cotton Candy 7 9 13 Pretzel 4 10 13 21 & Wheelchairs 3 Double Thunder Raceway 3-F 7 Black Hills 3-B 31 Miners Basin 9-A 9 Boomerang 3-E 5 Paratrooper 2-E 10 Tilt-A-Whirl 3-E Dip N Dots5 7 12 18 24 Pulled Pork 22 Gifts & Souvenirs 4 Sky Coaster 4-E 17 Bonneville 5-B 24 Oak 5-C 15 Bulgy the Whale 7-D 28 Puff 9-C 32 Turn of the Century 11-D Floats 9 16 23 Ribs 22 ATM LAGOON A BEACH 10 Bridger 4-B 36 Park Valley 8-A 40 Cliffhanger 11-E 44 Rattlesnake Rapids 10-A 38 Wicked 12-G Frozen 1 11 17 -

Section A. Feminist Theory in Late-Nineteenth-Century France, The

45 2 Section A. Feminist Theory In late-nineteenth-century France, the word féminisme, meaning women’s liberation was first used in political debates. The most generic way to define feminism is to say that it is an organized activity on behalf of women’s rights and common interests and based on the theory of the political, economic, and social equality of the sexes. Some initial forms of feminism were criticized for considering the perspective of only white, middle-class and educated people. Ethnically specific or multiculturalists forms of feminism were created as a reaction to this criticism. Most feminists believe that inequality between men and women are open to change because they are socially constructed. Many consider feminism as theory or theories, but some others see it as merely a kind of politics in the culture. Feminist theory aims to understand gender inequality and focus on sexuality, gender politics, and power relations. To achieve this, it has developed theories in a wide range of disciplines. Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into fields of theory or philosophy. Since in academic institutions ‘theory’ is often the male standpoint and feminists have fought hard to expose the fraudulent objectivity of male ‘science’, (for example, the Freudian theory of female sexual development) some feminists have not wished to embrace theory at all. Raman Selden, Widdowson and Brooker argue “Feminism and feminist criticism may be better termed a cultural politics than a theory or theories” (116). However, much recent feminist criticism wants to free itself from the ‘fixities and definites’ of theory and to develop a female discourse which is not considered as a belonging to a recognized conceptual position (and, therefore, probably male produced). -

Chapter 8 Mcloughlin and Za

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a chapter to be published in Writing the City in British Asian Diasporas. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/43693/ Chapter: McLoughlin, SM and Zavos, J (2012) Writing Religion in British Asian Diasporas. In: Writing the City in British Asian Diasporas. Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series . Routledge , 2012. ISBN 978-0415590242 White Rose Research Online [email protected] 8 Writing Religion in British Asian Diasporas Seán McLoughlin and John Zavos With vignettes from our five community-based events as starting points, the aim of this chapter is to better map and illuminate the changing roles of religion and its cognates such as faith, spirituality and the secular in the writing of British Asian diasporas. In particular, we are interested in the location and evident mobility of the category of religion in terms of the social relations and spatial scales that configure the relevant cityscapes. At the Peepul Centre in Leicester, for instance, the public visibility of neighbourhood institutions and places of worship came to the fore amidst discussion of the struggles to remake home abroad. Exchanges at Bradford‟s Mumtaz restaurant, by extension, demonstrated the impact of high profile arguments about the public recognition of religious belief and practice by the local state, with the Manchester event at the Indus 5 restaurant also underlining the growing national importance of a discourse of faith in education and the governance of community relations. -

Sikhism Reinterpreted: the Creation of Sikh Identity

Lake Forest College Lake Forest College Publications Senior Theses Student Publications 4-16-2014 Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity Brittany Fay Puller Lake Forest College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://publications.lakeforest.edu/seniortheses Part of the Asian History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Puller, Brittany Fay, "Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity" (2014). Senior Theses. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Lake Forest College Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Lake Forest College Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity Abstract The iS kh identity has been misinterpreted and redefined amidst the contemporary political inclinations of elitist Sikh organizations and the British census, which caused the revival and alteration of Sikh history. This thesis serves as a historical timeline of Punjab’s religious transitions, first identifying Sikhism’s emergence and pluralism among Bhakti Hinduism and Chishti Sufism, then analyzing the effects of Sikhism’s conduct codes in favor of militancy following the human Guruship’s termination, and finally recognizing the identity-driven politics of colonialism that led to the partition of Punjabi land and identity in 1947. Contemporary practices of ritualism within Hinduism, Chishti Sufism, and Sikhism were also explored through research at the Golden Temple, Gurudwara Tapiana Sahib Bhagat Namdevji, and Haider Shaikh dargah, which were found to share identical features of Punjabi religious worship tradition that dated back to their origins. -

To Better Serve and Sustain the South: How Nineteenth Century

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons at Buffalo State State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State History Theses History and Social Studies Education 8-2012 To Better Serve and Sustain the South: How Nineteenth Century Domestic Novelists Supported Southern Patriarchy Using the "Cult of True Womanhood" and the Written Word Daphne V. Wyse Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Jean E. Richardson, Ph.D., Associate Professor of History First Reader Michael S. Pendleton, Ph. D., Associate Professor of Political Science Department Chair Andrew D. Nicholls, Ph.D., Professor of History To learn more about the History and Social Studies Education Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to http://history.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Wyse, Daphne V., "To Better Serve and Sustain the South: How Nineteenth Century Domestic Novelists Supported Southern Patriarchy Using the "Cult of True Womanhood" and the Written Word" (2012). History Theses. Paper 8. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/history_theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Abstract During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, American women were subjected to restrictive societal expectations, providing them with a well-defined identity and role within the male- dominated culture. For elite southern women, more so than their northern sisters, this identity became integral to southern patriarchy and tradition. As the United States succumbed to sectional tension and eventually civil war, elite white southerners found their way of life threatened as the delicate web of gender, race, and class relations that the Old South was based upon began to crumble.