The Black Lives Movement in Context Pamela Oliver

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of Occupy Wall Street ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG NEW YORK OFFICE by Ethan Earle Table of Contents

A Brief History of Occupy Wall Street ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG NEW YORK OFFICE By Ethan Earle Table of Contents Spontaneity and Organization. By the Editors................................................................................1 A Brief History of Occupy Wall Street....................................................2 By Ethan Earle The Beginnings..............................................................................................................................2 Occupy Wall Street Goes Viral.....................................................................................................4 Inside the Occupation..................................................................................................................7 Police Evictions and a Winter of Discontent..............................................................................9 How to Occupy Without an Occupation...................................................................................10 How and Why It Happened........................................................................................................12 The Impact of Occupy.................................................................................................................15 The Future of OWS.....................................................................................................................16 Published by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, New York Office, November 2012 Editors: Stefanie Ehmsen and Albert Scharenberg Address: 275 Madison Avenue, Suite 2114, -

Striving for Anti-Racism: a Beginner's Journal!

Striving For Anti-Racism: A Beginner’s Journal BY BEYOND THINKING Special Thanks Anti-racism work does not happen in a vacuum. This journal would not be possible without the brilliance of Jennifer Wong, Karimah Edwards, Kyana Wheeler, Lauren Kite, and Cat Cuevas. Jennifer Wong, Creative Designer Attorney, and also the love of my life (!) Karimah Edwards, Editor Hummingbird Cooperative Kyana Wheeler, Anti-Racist Consultant and Advisor Kyana Wheeler Consulting Lauren Kite, Anti-Racist Consultant and Advisor Cat Cuevas, Anti-Racist Consultant and Advisor Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................4 How to Use This Journal........................................................ 7 I. WORKSHEETS & RESOURCES ................................. 9 Values ........................................................................................10 Emotions ................................................................................. 12 Racial Anxiety Self-Assessment (Round 1) .......14 Biases ........................................................................................ 16 Cultural Lenses ................................................................... 17 Privileges .................................................................................18 Privilege Bingo.................................................................... 19 Microaggressions .............................................................20 Common Forms of Resistance .............................. -

In Ta-Nehisi Coates's Between the World and Me

“OVERPOLICED AND UNDERPROTECTED”:1 RACIALIZED GENDERED VIOLENCE(S) IN TA-NEHISI COATES’S BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME “SOBREVIGILADAS Y DESPROTEGIDAS”: VIOLENCIA(S) DE GÉNERO RACIALIZADA(S) EN BETWEEN THE WORLD AND ME, DE TA-NEHISI COATES EVA PUYUELO UREÑA Universidad de Barcelona [email protected] 13 Abstract Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me (2015) evidences the lack of visibility of black women in discourses on racial profiling. Far from tracing a complete representation of the dimensions of racism, Coates presents a masculinized portrayal of its victims, relegating black women to liminal positions even though they are one of the most overpoliced groups in US society, and disregarding the fact that they are also subject to other forms of harassment, such as sexual fondling and other forms of abusive frisking. In the face of this situation, many women have struggled, both from an academic and a political-activist angle, to raise the visibility of the role of black women in contemporary discourses on racism. Keywords: police brutality, racism, gender, silencing, black women. Resumen Con la publicación de la obra de Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me (2015) se puso de manifiesto un problema que hacía tiempo acechaba a los discursos sobre racismo institucional: ¿dónde estaban las mujeres de color? Lejos de trazar un esbozo fiel de las dimensiones de la discriminación racial, la obra de Coates aboga por una representación masculinizada de las víctimas, relegando a las miscelánea: a journal of english and american studies 62 (2020): pp. 13-28 ISSN: 1137-6368 Eva Puyuelo Ureña mujeres a posiciones marginales y obviando formas de acoso que ellas, a diferencia de los hombres, son más propensas a experimentar. -

Real Democracy in the Occupy Movement

NO STABLE GROUND: REAL DEMOCRACY IN THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT ANNA SZOLUCHA PhD Thesis Department of Sociology, Maynooth University November 2014 Head of Department: Prof. Mary Corcoran Supervisor: Dr Laurence Cox Rodzicom To my Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is an outcome of many joyous and creative (sometimes also puzzling) encounters that I shared with the participants of Occupy in Ireland and the San Francisco Bay Area. I am truly indebted to you for your unending generosity, ingenuity and determination; for taking the risks (for many of us, yet again) and continuing to fight and create. It is your voices and experiences that are central to me in these pages and I hope that you will find here something that touches a part of you, not in a nostalgic way, but as an impulse to act. First and foremost, I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Laurence Cox, whose unfaltering encouragement, assistance, advice and expert knowledge were invaluable for the successful completion of this research. He was always an enormously responsive and generous mentor and his critique helped sharpen this thesis in many ways. Thank you for being supportive also in so many other areas and for ushering me in to the complex world of activist research. I am also grateful to Eddie Yuen who helped me find my way around Oakland and introduced me to many Occupy participants – your help was priceless and I really enjoyed meeting you. I wanted to thank Prof. Szymon Wróbel for debates about philosophy and conversations about life as well as for his continuing support. -

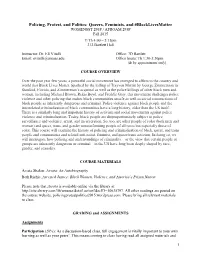

Policing, Protest, and Politics Syllabus

Policing, Protest, and Politics: Queers, Feminists, and #BlackLivesMatter WOMENSST 295P / AFROAM 295P Fall 2015 T/Th 4:00 – 5:15pm 212 Bartlett Hall Instructor: Dr. Eli Vitulli Office: 7D Bartlett Email: [email protected] Office hours: Th 1:30-3:30pm (& by appointment only) COURSE OVERVIEW Over the past year few years, a powerful social movement has emerged to affirm to the country and world that Black Lives Matter. Sparked by the killing of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman in Stanford, Florida, and Zimmerman’s acquittal as well as the police killings of other black men and women, including Michael Brown, Rekia Boyd, and Freddie Gray, this movement challenges police violence and other policing that makes black communities unsafe as well as social constructions of black people as inherently dangerous and criminal. Police violence against black people and the interrelated criminalization of black communities have a long history, older than the US itself. There is a similarly long and important history of activism and social movements against police violence and criminalization. Today, black people are disproportionately subject to police surveillance and violence, arrest, and incarceration. So, too, are other people of color (both men and women) and queer, trans, and gender nonconforming people of all races but especially those of color. This course will examine the history of policing and criminalization of black, queer, and trans people and communities and related anti-racist, feminist, and queer/trans activism. In doing so, we will interrogate how policing and understandings of criminality—or the view that certain people or groups are inherently dangerous or criminal—in the US have long been deeply shaped by race, gender, and sexuality. -

Co-Opting Identity: the Manipulation of Berberism, the Frustration of Democratisation, and the Generation of Violence in Algeria Hugh Roberts DESTIN, LSE

1 crisis states programme development research centre www Working Paper no.7 CO-OPTING IDENTITY: THE MANIPULATION OF BERBERISM, THE FRUSTRATION OF DEMOCRATISATION AND THE GENERATION OF VIOLENCE IN LGERIA A Hugh Roberts Development Research Centre LSE December 2001 Copyright © Hugh Roberts, 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this Working Paper should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Programme Working papers series no.1 English version: Spanish version: ISSN 1740-5807 (print) ISSN 1740-5823 (print) ISSN 1740-5815 (on-line) ISSN 1740-5831 (on-line) 1 Crisis States Programme Co-opting Identity: The manipulation of Berberism, the frustration of democratisation, and the generation of violence in Algeria Hugh Roberts DESTIN, LSE Acknowledgements This working paper is a revised and extended version of a paper originally entitled ‘Much Ado about Identity: the political manipulation of Berberism and the crisis of the Algerian state, 1980-1992’ presented to a seminar on Cultural Identity and Politics organized by the Department of Political Science and the Institute for International Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, in April 1996. Subsequent versions of the paper were presented to a conference on North Africa at Binghamton University (SUNY), Binghamton, NY, under the title 'Berber politics and Berberist ideology in Algeria', in April 1998 and to a staff seminar of the Government Department at the London School of Economics, under the title ‘Co-opting identity: the political manipulation of Berberism and the frustration of democratisation in Algeria’, in February 2000. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

Excessive Use of Force by the Police Against Black Americans in the United States

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Written Submission in Support of the Thematic Hearing on Excessive Use of Force by the Police against Black Americans in the United States Original Submission: October 23, 2015 Updated: February 12, 2016 156th Ordinary Period of Sessions Written Submission Prepared by Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Global Justice Clinic, New York University School of Law International Human Rights Law Clinic, University of Virginia School of Law Justin Hansford, St. Louis University School of Law Page 1 of 112 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary & Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Pervasive and Disproportionate Police Violence against Black Americans ..................................................................... 21 A. Growing statistical evidence reveals the disproportionate impact of police violence on Black Americans ................. 22 B. Police violence against Black Americans compounds multiple forms of discrimination ............................................ 23 C. The treatment of Black Americans has been repeatedly condemned by international bodies ...................................... 25 D. Police killings are a uniquely urgent problem ............................................................................................................. 25 II. Legal Framework Regulating the Use of Force by Police ................................................................................................ -

1. Petitions to Sign 2. Protestor Bail Funds 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations 4

Disclaimer and Credit: This is by no means comprehensive, but rather a list we hope you find helpful as a starting point to begin or to continue to support our Black brothers, sisters, communities and patients. Thank you to the Student National Medical Association chapter at George Washington University School of Medicine for compiling many of these resources. Editing Guidelines: Please feel free to add any resources that you feel are useful. Any inappropriate edits will be deleted and editing capabilities will be revoked. Table of Contents 1. Petitions To Sign 2. Protestor Bail Funds 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations 4. Mental Health Resources 5. Anti-Racism Reading and Resource List 6. Media 7. Voter Registration and Related Information 8. How to Support Memphis 1. Petitions To Sign *Please note that should you decide to sign a petition on change.org, DO NOT donate through change.org. Rather, donate through the websites specific to the organizations to ensure your donated funds are going directly to the organization. ● Justice for George Floyd ● Justice for Breonna ● Justice for Ahmaud Arbery ● We Can’t Breathe ● Justice for George Floyd 2. Protestor Bail Funds ● National Bail Fund Network (by state) ○ This link includes links to various cities ● Restoring Justice (Legal & Social services) 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations Actions are loud. As students, we know that money is tight. But if each of us donated just $5 to one cause, together we could demand a great impact. ● Black Visions Collective (Minnesota Based): “BLVC is committed to a long term vision in which ALL Black lives not only matter, but are able to thrive. -

Police Defunding and Reform : What Changes Are Needed? / by Olivia Ghafoerkhan

® About the Authors Olivia Ghafoerkhan is a nonfiction writer who lives in northern Virginia. She is the author of several nonfiction books for teens and young readers. She also teaches college composition. Hal Marcovitz is a former newspaper reporter and columnist who has written more than two hundred books for young readers. He makes his home in Chalfont, Pennsylvania. © 2021 ReferencePoint Press, Inc. Printed in the United States For more information, contact: ReferencePoint Press, Inc. PO Box 27779 San Diego, CA 92198 www.ReferencePointPress.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, web distribution, or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. Picture Credits: Cover: ChameleonsEye/Shutterstock.com 28: katz/Shutterstock.com 6: Justin Berken/Shutterstock.com 33: Vic Hinterlang/Shutterstock.com 10: Leonard Zhukovsky/Shutterstock.com 37: Maury Aaseng 14: Associated Press 41: Associated Press 17: Imagespace/ZUMA Press/Newscom 47: Tippman98x/Shutterstock.com 23: Associated Press 51: Stan Godlewski/ZUMA Press/Newscom LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING- IN- PUBLICATION DATA Names: Ghafoerkhan, Olivia, 1982- author. Title: Police defunding and reform : what changes are needed? / by Olivia Ghafoerkhan. Description: San Diego, CA : ReferencePoint Press, 2021. | Series: Being Black in America | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020048103 (print) | LCCN 2020048104 (ebook) | ISBN 9781678200268 (library binding) | ISBN 9781678200275 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Police administration--United States--Juvenile literature. | Police brutality--United States--Juvenile literature. | Discrimination in law enforcement--United States--Juvenile literature. -

Fresno-Commission-Fo

“If you are working on a problem you can solve in your lifetime, you’re thinking too small.” Wes Jackson I have been blessed to spend time with some of our nation’s most prominent civil rights leaders— truly extraordinary people. When I listen to them tell their stories about how hard they fought to combat the issues of their day, how long it took them, and the fact that they never stopped fighting, it grounds me. Those extraordinary people worked at what they knew they would never finish in their lifetimes. I have come to understand that the historical arc of this country always bends toward progress. It doesn’t come without a fight, and it doesn’t come in a single lifetime. It is the job of each generation of leaders to run the race with truth, honor, and integrity, then hand the baton to the next generation to continue the fight. That is what our foremothers and forefathers did. It is what we must do, for we are at that moment in history yet again. We have been passed the baton, and our job is to stretch this work as far as we can and run as hard as we can, to then hand it off to the next generation because we can see their outstretched hands. This project has been deeply emotional for me. It brought me back to my youthful days in Los Angeles when I would be constantly harassed, handcuffed, searched at gunpoint - all illegal, but I don’t know that then. I can still feel the terror I felt every time I saw a police cruiser.