Harrison Birtwistle Interview: the ‘Difficult’ Composer on Taking the Mask of Orpheus Back to ENO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Roots of Birtwistle's Theatrical Expression

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89534-7 - Harrison Birtwistle’s Operas and Music Theatre David Beard Excerpt More information 1 The roots of Birtwistle’s theatrical expression: from Pantomime to Down by the Greenwood Side With six major operas, around eight music dramas, and a body of incidental music to his name, Harrison Birtwistle has made a significant contribution to contemporary opera and music theatre during a period that spans more than forty years. This study is concerned not only to reflect the importance of these stage works by examining them in some detail but also to convey their varied musical and intellectual worlds. Previous studies have rightly focused on Birtwistle’s perennial concerns, such as myth, ritual, cyclical journeys, varied repetition, verse–refrain structures, instrumental role-play, layers and lines.1 These characteristics highlight consistency throughout Birtwistle’s oeuvre and are a mark of his formalist stance. By contrast, this book is motivated by a belief that the stage works – in which instrumental and physical drama, song and narrative are combined – demand interpre- tation from multiple, inter-disciplinary perspectives. While not denying obvious or important relations between works, what follows is rather more focused on differences: Birtwistle’s choice of contrasting narrative subjects, his collaborations with nine librettists, his varied pre-compositional ideas and working methods, his experience with different directors, producers and others, all distinguish one stage work from another. A recurring theme is therefore a consideration of ways in which Birtwistle’s initial concepts are informed, altered or conveyed differently in each case. Moreover, as ideas evolve, from the composer’s musical sketches to the final production, mul- tiple meanings accrue that are particular to each drama. -

Gardner • Even Orpheus Needs a Synthi Edit No Proof

James Gardner Even Orpheus Needs a Synthi Since his return to active service a few years ago1, Peter Zinovieff has appeared quite frequently in interviews in the mainstream press and online outlets2 talking not only about his recent sonic art projects but also about the work he did in the 1960s and 70s at his own pioneering computer electronic music studio in Putney. And no such interview would be complete without referring to EMS, the synthesiser company he co-founded in 1969, or namechecking the many rock celebrities who used its products, such as the VCS3 and Synthi AKS synthesisers. Before this Indian summer (he is now 82) there had been a gap of some 30 years in his compositional activity since the demise of his studio. I say ‘compositional’ activity, but in the 60s and 70s he saw himself as more animateur than composer and it is perhaps in that capacity that his unique contribution to British electronic music during those two decades is best understood. In this article I will discuss just some of the work that was done at Zinovieff’s studio during its relatively brief existence and consider two recent contributions to the documentation and contextualization of that work: Tom Hall’s chapter3 on Harrison Birtwistle’s electronic music collaborations with Zinovieff; and the double CD Electronic Calendar: The EMS Tapes,4 which presents a substantial sampling of the studio’s output between 1966 and 1979. Electronic Calendar, a handsome package to be sure, consists of two CDs and a lavishly-illustrated booklet with lengthy texts. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

October 2012

21ST CENTURY MUSIC OCTOBER 2012 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $96.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $48.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $12.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2012 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Copy should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors are encouraged to submit via e-mail. Prospective contributors should consult The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), in addition to back issues of this journal. -

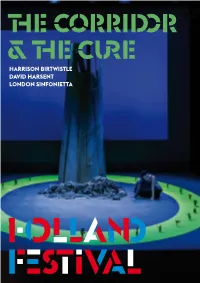

The-Corridor-The-Cure-Programma

thE Corridor & thE curE HARRISON BIRTWISTLE DAVID HARSENT LONDON SINFONIETTA INHOUD CONTENT INFO 02 CREDITS 03 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA EN IK 05 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA AND ME 10 OVER DE ARTIESTEN 14 ABOUT THE ARTISTS 18 BIOGRAFIEËN 16 BIOGRAPHIES 20 HOLLAND FESTIVAL 2016 24 WORD VRIEND BECOME A FRIEND 26 COLOFON COLOPHON 28 1 INFO DO 9.6, VR 10.6 THU 9.6, FRI 10.6 aanvang starting time 20:30 8.30 pm locatie venue Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ duur running time 2 uur 5 minuten, inclusief een pauze 2 hours 5 minutes, including one interval taal language Engels met Nederlandse boventiteling English with Dutch surtitles inleiding introduction door by Ruth Mackenzie (9.6), Michel Khalifa (10.6) 19:45 7.45 pm context za 11.6, 14:00 Sat 11.6, 2 pm Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam Workshop Spielbar: speel eigentijdse muziek play contemporary music 2 Tim Gill, cello CREDITS Helen Tunstall, harp muziek music orkestleider orchestra manager Harrison Birtwistle Hal Hutchison tekst text productieleiding production manager David Harsent David Pritchard regie direction supervisie kostuums costume supervisor Martin Duncan Ilaria Martello toneelbeeld, kostuums set, costume supervisie garderobe wardrobe supervisor Alison Chitty Gemma Reeve licht light supervisie pruiken & make-up Paul Pyant wigs & make-up supervisor Elizabeth Arklie choreografie choreography Michael Popper voorstellingsleiding company stage manager regie-assistent assistant director Laura Thatcher Marc Callahan assistent voorstellingsleiding sopraan soprano deputy stage manager Elizabeth Atherton -

Juilliard Percussion Ensemble Daniel Druckman , Director Daniel Parker and Christopher Staknys , Piano Zlatomir Fung , Cello

Monday Evening, December 11, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Percussion Ensemble Daniel Druckman , Director Daniel Parker and Christopher Staknys , Piano Zlatomir Fung , Cello Bell and Drum: Percussion Music From China GUO WENJING (b. 1956) Parade (2003) SAE HASHIMOTO EVAN SADDLER DAVID YOON ZHOU LONG (b. 1953) Wu Ji (2006) CHRISTOPHER STAKNYS, Piano BENJAMIN CORNOVACA LEO SIMON LEI LIANG (b. 1972) Inkscape (2014) DANIEL PARKER, Piano TYLER CUNNINGHAM JAKE DARNELL OMAR EL-ABIDIN EUIJIN JUNG Intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. CHOU WEN-CHUNG (b. 1923) Echoes From the Gorge (1989) Prelude: Exploring the modes Raindrops on Bamboo Leaves Echoes From the Gorge, Resonant and Free Autumn Pond Clear Moon Shadows in the Ravine Old Tree by the Cold Spring Sonorous Stones Droplets Down the Rocks Drifting Clouds Rolling Pearls Peaks and Cascades Falling Rocks and Flying Spray JOSEPH BRICKER TAYLOR HAMPTON HARRISON HONOR JOHN MARTIN THENELL TAN DUN (b. 1957) Elegy: Snow in June (1991) ZLATOMIR FUNG, Cello OMAR EL-ABIDIN BENJAMIN CORNOVACA TOBY GRACE LEO SIMON Performance time: Approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including one intermission Notes on the Program Scored for six Beijing opera gongs laid flat on a table, Parade is an exhilarating work by Jay Goodwin that amazes both with its sheer difficulty to perform and with the incredible array of dif - “In studying non-Western music, one ferent sounds that can be coaxed from must consider the character and tradition what would seem to be a monochromatic of its culture as well as all the inherent selection of instruments. -

Baroque 1590-1750 Classical 1750-1820

Period Year Opera Composer Notes A pastoral drama featuring a Dafne new style of sung dialogue, 1597 Jacopo Peri more expressive than speech but less melodious than song The first opera to survive 1600 Euridice Jacopo Peri in tact The earliest opera still 1607 Orfeo Claudio Monteverdi performed today Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria Claudio Monteverdi 1639 (The Return of Ulysses) L’incoronazione di Poppea 1643 (The Coronation of Poppea) Claudio Monteverdi 1647 Ofeo Luigi Rossi 1649 Giasone Francesco Cavalli 1651 La Calisto Francesco Cavalli 1674 Alceste Jean-Baptiste Lully 1676 Atys Jean-Baptiste Lully Venus and Adonis John Blow Considered the first English 1683 opera 1686 Armide Jean-Baptiste Lully 1689 Dido and Aeneas Henry Purcell Baroque 1590-1750 1700 L’Eraclea Alessandro Scarlatti 1710 Agrippina George Frederick Handel 1711 Rinaldo George Frederick Handel 1721 Griselda Alesandro Scarlatti 1724 Giulio Cesere George Frederick Handel 1728 The Beggar’s Opera John Gay 1731 Acis and Galatea George Frederick Handel La serva padrona 1733 (The Servant Turned Giovanni Battista Pergolesi Mistress) 1737 Castor and Pollux Jean-Philippe Rameau 1744 Semele George Frederick Handel 1745 Platee Jean-Philippe Rameau La buona figliuola 1760 (The Good-natured Girl) Niccolò Piccinni 1762 Orfeo ed Euridice Christoph Willibald Gluck 1768 Bastien und Bastienne Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart’s first opera Il mondo della luna 1777 (The World on the Moon) Joseph Haydn 1779 Iphigénie en Tauride Christoph Willibald Gluck 1781 Idomeneo Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart’s -

Wiebe, Confronting Opera

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/02690403.2017.1286132 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Wiebe, H. (2020). Confronting Opera in the 1960s: Birtwistle’s Punch and Judy. Journal of the Royal Musical Association , 142(1), 173-204. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690403.2017.1286132 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Time of Music Schedule 2017

Tuesday 4.7.2017 Meet the composer: Steven Kazuo Takasugi, players from Talea Ensemble and Sideshow Tuesday 4.7. at 18.00 School centre Meeting with the composer and performers of the opening concert, interviewed by artistic director Johan Tallgren. Sideshow Tuesday 5.7. at 19.00 Viitasaari Areena Tickets 27 / 15 € Opening concert of the festival Aphorisms on how to survive in the world Talea Ensemble: Barry J. Crawford, flute Rane Moore, clarinet Michael Ibrahim, saxophone Stephen Gosling, piano Alex Lipowski, percussion Emilie-Anne Gendron, violin Elizabeth Weisser Helgeson, viola Kevin McFarland, cello Timo Kurkikangas, Anders Pohjola, electronics Steven Kazuo Takasugi: Sideshow (2009-15) 60′ for amplified octet and electronic playback in five movements Written for Alex Lipowski and the Talea Ensemble Wednesday 5.7.2017 Finnish Gates & Ciphers Wednesday 5.7. at 15.00 Tervamäki Chapel Tickets 15 / 8 € Jukka Tiensuu: Plus II 8´ Ville Raasakka: Short cuts 4´ Kaija Saariaho: New Gates 13´ Max Savikangas: Kranker Matthäus 8 ´ Outi Tarkiainen: Sanasi, kiveen uponneet 7 ´ Lotta Wennäkoski: Ciphers 13´ Uusinta Ensemble Malla Vivolin, flute Lauri Sallinen, clarinet Lily-Marlene Puusepp, harp Max Savikangas, viola Markus Hohti, cello There is a bus transportation to the concert leaving at 14 from Viitasaari bus station and returning after the concert. The price of the return ticket is 10 €. String Quartet: The Politics of Gesture Wednesday 5.7. at 18.00 Viitasaari Chapel Tickets 22 / 12 € Quatuor Bozzini: Clemens Merkel, violin Alissa Cheung, violin Stéphanie Bozzini, viola Isabelle Bozzini, cello Mauricio Kagel: Streichquartett II (1967) 10´ Mark Applebaum: Darmstadt Kindergarten (2015) 7´ Mauricio Kagel: Streichquartett I (1967) 10´ — Anthony Vine: Between Blue (2016) 15´ James Dillon: Third String Quartet (1998) 18´ Meet the composer: James Dillon Wednesday 5.7. -

The Current Great Gate of Kiev Built in 1982 in Kyiv, Ukraine. Photo: ©Mark Laycock

The current Great Gate of Kiev built in 1982 in Kyiv, Ukraine. Photo: ©Mark Laycock Nieweg Chart Pictures at an Exhibition; Картинки c выставки; Kartinki s vystavki; Tableaux d'une Exposition By Modeste Mussorgsky A Guide to Editions Up Date 2018 Clinton F. Nieweg 1. Orchestra editions 2. String Orchestra editions 3. Wind Ensemble/Band editions 4. Chamber Ensemble editions 5. Other non-orchestral arrangements 6. Keyboard editions 7. Sites, Links and Documentation about the 'Pictures' 8. Reference Sources 9. Publishers and Agents In this chart the composer’s name is spelled as cataloged by the publishers. They use Модест Мусоргский, Moussorgski, Musorgskii, Musorgskij, Musorgsky, Mussorgskij, or Mussorgsky. He was inspired to compose Pictures at an Exhibition quickly, completing the piano score in three weeks 2–22 June 1874. Movement Codes 1. Promenade I 2. Gnomus 3. Promenade II 4. The Old Castle 5. Promenade III 6. Tuileries: Children Quarreling at Play 7. Bydło 8. Promenade IV 9. Ballet of Unhatched Chicks 10. Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuÿle 11. Promenade V 12. The Market Place at Limoges - Le Marché 13. Catacombæ (Sepulcrum Romanum) 14. Cum Mortuis in Lingua Mortua 15. Hut on Fowl’s Legs (Baba-Yaga) 16. The Great Gate of Kiev Recordings: For information about recordings of all 606 known arrangements and 1041 recordings (as of August 2015), see the chart by David DeBoor Canfield, President, International Kartinki s vystavki Association. www.daviddeboorcanfield.org Click on Exhibition. Click on Arrangements. For the August 2018 update of 1112 recordings see Canfield in Sites, Links and Documentation about the 'Pictures' below. -

The Anguished Cry of Orpheus Has Haunted Harrison Birtwistle All His Composing Life

Hilary Finch The Times 17 August 2009 Euridice! The anguished cry of Orpheus has haunted Harrison Birtwistle all his composing life. This summer he wrote a new Orpheus piece; and, while we wait for a long-overdue new production of his great opera The Mask of Orpheus (premiered in 1986), the Proms has boldly presented a semi-staging of its central act. This focuses on Orpheus’ journey to the Underworld to retrieve Euridice, except that this time he never gets there. It’s all a dream — with some of Birtwistle’s most sensuously lyrical and light-dappled music turning to a nightmare of rhythmic distortion, layering, and electronic sampling — and with a strangely potent awakening. Thanks to the superb playing of the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Martyn Brabbins, the skilful sound design of Ian Dearden and thoughtful stage direction by Tim Hopkins — including a glittering of hand mirrors — this was unforgettable. Paul Driver Sunday Times 23 August 2009 Orpheus made an overt connection with a work by Harrison Birtwistle in that BBCSO concert: his prodigious electro-acoustic opera, The Mask of Orpheus, whose relentlessly dissonant, hour-long central act (The Arches) was given a stunning concert rendering with the help of the BBC Singers. Andrew Clements Guardian ***** Monday 17 August 2009 The Mask of Orpheus is Harrison Birtwistle's masterpiece and the finest British opera of the last half-century, but the score's scale and complexity have conspired to limit its opportunities – there has been just one complete performance in concert since the premiere at ENO in 1986. Even as part of its celebration of Birtwistle's 75th birthday, the resources of the Proms couldn't run to programming the whole work, so Martyn Brabbins and Ryan Wigglesworth conducted just the hour-long second act, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and BBC Singers, and a cast led by Alan Oke as Orpheus the Man. -

Orfeo 20 Sa Pour

SAISON 13-14 L’ORFEO DE MONTEVERDI Dossier Dossier Pédagogique Pour sa 20e édition, l’Académie baroque européenne d’Ambronay retourne aux sources de l’opéra. L’Orfeo, fable en musique écrite par Claudio Monteverdi en 1607, est souvent considéré comme le premier véritable opéra de l’histoire, une œuvre musicalement intense, dont le livret est directement inspiré des Métamorphoses d’Ovide. La richesse de l’orchestration, la virtuosité des pages chorales, la caractérisation très précise des différents rôles font de cette œuvre le terrain de jeu idéal pour ces talents émergents. Coproduction : Centre culturel de rencontre d’Ambronay, Théâtre de Bourg- SAMEDI 19 OCTOBRE : 20h30 en-Bresse, Opéra Théâtre de Saint-Étienne DIMANCHE 20 OCTOBRE : 15h30 et Opéra de Reims. Cette production SPECTACLE EN ITALIEN SURTITRE EN FRANÇAIS bénéficie du soutien de la fondation DUREE DU SPECTACLE : 2 HEURES AVEC ENTRACTE Orange. Sommaire L’ORFEO DE MONTEVERDI ................................................................................................................ 3 SYNOPSIS ......................................................................................................................................... 3 CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI 1567-1643 .............................................................................................. 5 LE LIBRETTISTE : ALESSANDRO STRIGGIO 1573-1630 ........................................................... 6 FICHE IDENTITE DE L’ŒUVRE .....................................................................................................