Expanding the Horizon from Barnstormers to Mainstream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Women in Aviation Through World War I

United States Women in Aviation through World War I Claudia M.Oakes •^ a. SMITHSONIAN STUDIES IN AIR AND SPACE • NUMBER 2 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given sub stantive review. -

Ownershipindividual Or Group? B:8.125” T:7.875” S:7.375”

AUGUST 2020 OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB SO, YOU WANT TO BUY A PITTS? TALE OF TWO LLCS AIRCRAFT OWNERSHIPINDIVIDUAL OR GROUP? B:8.125” T:7.875” S:7.375” CGI image. Pre-production models shown. B:10.75” T:10.5” S:10” 2-DOOR 4-DOOR SPORT RESERVE YOURS NOW AT FORD.COM DOC. NAME: FMBR0151000_Bronco_SportAerobatics_Manifesto_10.75x7.875_01.indd LAST MOD.: 6-22-2020 5:51 PM CLIENT: FORD ECD: Karl Lieberman BLEED: 10.75” H x 8.125” W DOC PATH: Macintosh HD:Users:nathandalessandro:Desktop:FRDNSUVK0158_Bronco_Manifesto_Print:FMBR0151000_ Bronco_SportAerobatics_Manifesto_10.75x7.875_01.indd CAMPAIGN: Bronco Reveal CD: Stuart Jennings & Eric Helin TRIM: 10.5” H x 7.875” W FONTS: Ford Antenna Cond (Regular; OpenType) BILLING #: FRDNSUVK0158 CW: None VIEWING: 10.5” H x 7.875” W COLORS: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black MEDIA: Print AD: Alex McClelland SAFETY: 10” H x 7.375” W EXECUTION: Manifesto – Sport Aerobatics AC: Jamie Robinson, Mac Hall SCALE: 1” = 1” SD: Nathan Dalessandro FINAL TRIM: 10.5” H x 7.875” W PD: Ashley Mehall PRINT SCALE: None IMAGES: FRDNSUVK0158_Bronco_silhouette_family_V2_09_Flipped_CMYK.tif (914 ppi; CMYK; Users:nathandalessandro:Desktop:FRDNSUVK0158_Bronco_silhouette_family_V2_09_Flipped_CMYK.tif; Up to Date; 32.81%) Bronco_BW_Stacked_KO_wk.eps (Users:nathandalessandro:Desktop:BRONCO_ASSETS:_Bronco_LogoPack:Bronco_BW_Stacked_KO_wk.eps; Up to Date; 38.25%) EAA_PartnerRecognition_Rv_PK.eps (Creative:FORD:~Ford_MasterArt:2019:Outsourced:Originals:EAA_Logo:EAA_PartnerRecognition_Rv_PK.eps; Up to Date; 23.79%) BFP_OOH_PRINT_WHITE_KO.eps (Creative:WK_LOGOS:FORD_wk:_Built_Ford_Proud:OOH_PRINT:BFP_OOH_PRINT_WHITE_KO.eps; Up to Date; 43.28%) Vol. 49 No. 8 / AUGUST 2020 A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB Publisher: Robert Armstrong, [email protected] Executive Director: Stephen Kurtzahn, [email protected], 920-426-6574 Editor: Lorrie Penner, [email protected] Contributing Authors: Robert Armstrong, Lynn Bowes, Budd Davisson, Lawrence V. -

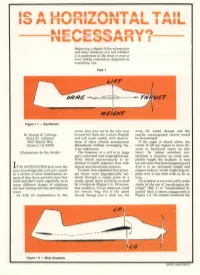

Is a Horizontal Tail Necessary?

IO A LJ/'M-MTr/'MkJT A I All I I AMU Kl ADX/O Beginning digesta elementary ofthe basicand functions oftaila whether it is positioned at the front or rear or even hiding somewhere disguisedas something else. Parti FigurEquilibriu— 1 e1- m series, they may not be the only ones wing lift would change and the GeorgeBy CollingeB. aroun plain t thesi dbu e n e ar Englis h exactly counterpoised vectors would (EAA 67, Lifetime) and will mesh readily with observa- be disarranged. 5037 MarlinWay tions of other related aerodynamic e anglIth f f attaco e k alterse th , Oxnard, 93030CA phenomena without revamping the- cente f lifo r t (cp) begin movo st e for- ories midstream. ward or backward (more on this Illustrations by the Author The business of a tail is in large later) o unlesS . s somehow con- part, concerned with longitudinal sta- strained a runawa, p coulc y d com- bility which conventionally is ex- pletely toppl e airplaneth e reaA . r amine itselfn di , separate from both tail prevents this from happening and IT IS ANTICIPATED that even the lateral and directional stability. n extremela n doei t i s y simpld an e most knowledgeable will give assent To start, airplane'n a f i s four princi- elegant fashion, which might hel- pex to a review of some fundamental as- pal forces were hypothetically bal s beeo -s ha nr t i witplaifo y s hu nwh pects of why there are tails, how they anced through a single point at a long. -

San Diego Union-Tribune Photograph Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6r29q3mg No online items Guide to the San Diego Union-Tribune Photograph Collection Rebecca Gerber, Therese M. James, Jessica Silver San Diego Historical Society Casa de Balboa 1649 El Prado, Balboa Park, Suite 3 San Diego, CA 92101 Phone: (619) 232-6203 URL: http://www.sandiegohistory.org © 2005 San Diego Historical Society. All rights reserved. Guide to the San Diego C2 1 Union-Tribune Photograph Collection Guide to the San Diego Union-Tribune Photograph Collection Collection number: C2 San Diego Historical Society San Diego, California Processed by: Rebecca Gerber, Therese M. James, Jessica Silver Date Completed: July 2005 Encoded by: Therese M. James and Jessica Silver © 2005 San Diego Historical Society. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: San Diego Union-Tribune photograph collection Dates: 1910-1975 Bulk Dates: 1915-1957 Collection number: C2 Creator: San Diego union-tribune Collection Size: 100 linear ft.ca. 150,000 items (glass and film negatives and photographic prints): b&w and color; 5 x 7 in. or smaller. Repository: San Diego Historical Society San Diego, California 92138 Abstract: The collection chiefly consists of photographic negatives, photographs, and news clippings of San Diego news events taken by staff photographers of San Diego Union-Tribune and its predecessors, San Diego Union, San Diego Sun, San Diego Evening Tribune, and San Diego Tribune-Sun, which were daily newspapers of San Diego, California, 1910-1974. Physical location: San Diego Historical Society Research Library, Booth Historical Photograph Archives, 1649 El Prado, Casa de Balboa Building, Balboa Park, San Diego, CA 92101 Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open for research. -

Pioneers of Flight U.S

National Park Service Pioneers of Flight U.S. Department of the Interior Presi io of San Francisco Gol en Gate National Recreation Area GGNRA Park Archives Crissy Airfield in 1919. Death-Defying Firsts at Have you ever been scared during an advance the military potential of airplanes Crissy Fiel airplane flight? Most of us have at one time proven by their success in World War I. or another even in today’s very safe But even before the airfield’s completion aircraft. However during the pioneering in 1921 it had already seen aviation history days of flight every trip was death-defying being made. As early as 1915 crowds and possibly one’s last. gathered here to see if the “father of aerobatics” perform daring feats at the The early pilots flying in and out of Crissy Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Field performed many aviation firsts putting their life on the line every day to Standing on the grass of Crissy Field today prove that airplanes were useful and we can only imagine the wild cheers as the reliable. Their contributions and first flight around the world landed or the GGNRA Park Archives commitment played a key role in making fearful good-byes as the first flight to Pilo s ook heir families up o air travel safe and routine for all. In 1919 Hawaii departed. Crissy Field saw all these prove ha aircraf were safe. the army built an airfield on the Presidio to daring landmark events and more. “Father of Aerobatics” Even in the early years of aviation Lincoln main attraction flying over what would Beachey the father of aerobatics knew become Crissy Field. -

State Archives of North Carolina Tiny Broadwick Pioneer of Aviation Biography Table of Contents Biography

State Archives of North Carolina Tiny Broadwick Pioneer of Aviation Biography Table of Contents Biography Pages 1-4 Tiny Broadwick biography Page 5 Charles Broadwick biography Page 6 Glenn Martin biography Lesson Guide Page 1-2 Balloon facts Page 3-15 Lesson guides Page 16 Video, Fort Bragg 1964 Page 17 Video, WRAL interview, 1963 Page 18 Museum of history images Page 19 News & Observer newspaper clipping Page 20-21 Awards and honors Page 22 Sources eorgia Ann Thompson was born April 8, 1893 in Granville County, North Carolina. She was the seventh and youngest daughter of George G and Emma Ross Thompson. As an infant she was very small, weighing only three pounds when she was born. For that reason she was called “Tiny”. She remained small even as an adult, topping out at a little over 4 feet tall and weighing 80 pounds. When she was six years old the family moved to Hen- derson in Vance County. Ms. Thompson’s early life was difficult both as a child and in early adulthood. In 1905 she married William A. Jacobs and had one daughter in 1906. Her husband abandoned her shortly thereafter. In 1907 Thompson attended the North Carolina State Fair and saw an aerial show that featured Charles Broad- wick. He went up in a hot air balloon, climbed over the side and parachuted back down to earth. Tiny was de- termined to join his act. “When I saw that balloon go up, I knew that’s all I ever wanted to do!” She spoke with Charles Broadwick and asked to become part of his show. -

MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB Vol

FEBRUARY 2011 OFFICIAL MAGAZINEMAGAZINE ofof thethe INTERNATIONALINTERNATION AEROBATIC CLUB Memories of IAC Living a Dream It’s gonna be Save on your AirVenture tickets. Buy online now at AirVenture.org/tickets a big day. All week long. This year we’ve packed each day (and evening) of AirVenture with special events and attractions you’ll want to plan around. Monday, July 25 Opening Day Concert Tuesday, July 26 Tribute to Bob Hoover Wednesday, July 27 Navy Day Thursday, July 28 Tribute to Burt Rutan Friday, July 29 Salute to Veterans Saturday, July 30 Night Air Show Returns Sunday, July 31 Big Finale, the Military Scramble Join us for a big celebration of the 100th Anniversary of Naval Aviation. See it all, from the Curtiss Pusher replica to the Navy’s hottest hardware. All week long. Advance tickets made possible by OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB Vol. 40 No.2 February 2011 A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB CONTENTS “I always knew I’d build an airplane someday.” Jim Doyle FEATURES 06 A Biplane of Our Own Building a Skybolt Jim Doyle 14 Living a Dream David Prince 22 Reflections on the IAC Bill Finagin COLUMNS 03 / President’s Page Doug Bartlett 24 / Just for Starters Greg Koontz 26 / Safety Corner Steve Johnson DEPARTMENTS 02 / Letter From the Editor 04 / IAC News Briefs 27 / Tech Tips Vicki Cruse THE COVER 30 / Advertisers Index Jim Doyle with his 31 / FlyMart and Classifieds Skybolt. Photo by Brian Kaminski PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRIAN KAMINSKI REGGIE PAULK COMMENTARY / EDITOR’S LOG OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB PUBLISHER: Doug Bartlett IAC MANAGER: Trish Deimer EDITOR: Reggie Paulk SENIOR ART DIRECTOR: Phil Norton DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: Mary Jones COPY EDITOR: Colleen Walsh CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Doug Bartlett Greg Koontz Vicki Cruse Reggie Paulk Jim Doyle David Prince Steve Johnson IAC CORRESPONDENCE International Aerobatic Club, P.O. -

DICKINSON COUNTY HISTORY – TRANSPORTATION – AIRPLANES [Compiled & Transcribed by William J

DICKINSON COUNTY HISTORY – TRANSPORTATION – AIRPLANES [Compiled & Transcribed by William J. Cummings] EARLY AIR EAGLE WILL SCREAM TRANSPORTATION _____ Iron Mountain Press, Iron Mountain, Iron Mountain Is Planning Dickinson County, Michigan, Volume 17, Biggest Celebration Number 15 [Thursday, August 29, in the U.P. 1912], page 1, column 6 _____ MAY BE VISITED The call issued by Mayor Cruse for a BY AEROPLANE meeting of citizens to consider the matter of _____ a Fourth of July celebration was held at the city hall last Monday evening and was well Only Aeroplane Built in U.P. to Make attended. Maiden Flight Soon. The meeting was opened by his honor, who after stating the object of the meeting, If the Iron Mountain people should voiced a desire to make the celebration a awaken some morning and gazing upward county affair and invite Norway neighbors to see a huge, bird-like object flying over their participate in the “doings.” housetops they should neither summon A temporary organization was perfected help nor run for their shot-guns [sic – by the election of Mayor Cruse as chairman shotguns], as it will only be an aeroplane, and S. Rex Plowman performed the duties invented and constructed by E.E. Lesard, of scribe. formerly of St. Louis, machinist at the Frank M. Milliman, Henry LaFountaine Negaunee garage of Charles J.A. Forell, and John Andrews, Jr., were named a Jr. Mr. Lessard is seriously thinking of committee on permanent organization. A flying with his hydro-aeroplane in this general committee of arrangements was direction for the purpose of demonstrating named, as follows: Louis J. -

A-CR-CCP-805/PF-001 Attachment a to EO C570.01 Instructional Guide

A-CR-CCP-805/PF-001 Attachment A to EO C570.01 Instructional Guide SECTION 1: THE ORIGIN OF AEROBATIC FLIGHT SECTION 2: AIRCRAFT DEVELOPMENT SECTION 3: MODERN AEROBATIC DISPLAYS SECTION 4: CANADIAN AEROBATIC TEAMS C570.01A-1 A-CR-CCP-805/PF-001 Attachment A to EO C570.01 Instructional Guide SECTION 1 THE ORIGIN OF AEROBATIC FLIGHT ORIGIN Pre-World War I (WWI) Did you know? The first time the Wright brothers made a 360-degree banked turn, the idea of aircraft development for more thrilling control of an aircraft started. With the development of the aircraft in 1904, each new aircraft manoeuvre was more thrilling to the public. Large paying audiences soon tired of watching pilots perform simple flying exhibits and demanded more thrills and danger. Pilots competed to develop flying tricks and stunts leading to aerobatic manoeuvres. Did you know? Flying clubs were created soon after the development of the aircraft. To teach new pilots how to fly and handle the numerous new aircraft being developed, clubs were created by individuals and builders such as Curtis. In 1905, Count Henri de la Vauix, vice-president of the Aero Club of France gave a presentation to the Olympic Congress of Brussels for the formation of a universal aeronautical federation to regulate the various aviation meetings and advance the science and sport of aeronautics. The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) was formed by countries including: Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, and The US. Daredevils Did you know? A daredevil is defined as a reckless, impulsive, and irresponsible person. -

Of Wings & Things. Aeronautics Information Stuff & Things for Students & Teachers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 170 SE 053 549 AUTHOR Poff, Norman 0., Ed. TITLE Of Wings & Things. Aeronautics Information Stuff & Things for Students & Teachers. INSTITUTION Oklahoma State Univ., Stillwater. Aerospace Education Services Project. SPONS AGENCY National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 91p. AVAILABLE FROMAerospace Education Services Project, 300 N. Cordell, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078-0422. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Education; Aircraft Pilots; Elementary School Science; Elementary Secondary Education; Mathematics Education; Models; Physical Sciences; *Science Activities; *Science Education; *Science Instruction; Scientific Concepts; Scientific Literacy; Secondary School Science IDENTIFIERS *Aeronautics; Aircraft Design; Airplane Flights; *Paper Airplanes (Toys) ABSTRACT This book presents information, activities, and paper models related to aviation. Most of the models and activities included use a one page, single concept format. All models and activities are designed to reinforce, clarify,or expand on a concept, easily and quickly. A list of National Aeronautics and Sace Administration (NASA) Center education programs officers,a list of NASA teacher resource centers and 18 sources of additional information are provided.(PR) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by FDRS are the best thatcan be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** AERONAUTICS INORMAT N STUFF THINGS FOR STUDENTS & TEACHERS a. 1990 EDITION NORMAN O. POFF NASAJAESP 300 N. CORDELL U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OKLAHOMA STATE Office of Educational Research and improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION UNIVERSITY CENTER (ERIC) Obisdocument has been reproduced as received from the person or organization STILLWATER. -

Flying in the 1920S

Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research Volume 22 Number 1 JAAER Fall 2012 Article 4 Fall 2012 Flying in the 1920s Joseph F. Clark III Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/jaaer Scholarly Commons Citation Clark, J. F. (2012). Flying in the 1920s. Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research, 22(1). Retrieved from https://commons.erau.edu/jaaer/vol22/iss1/4 This Forum is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clark: Flying in the 1920s The Barnstormers FORUM FLYING IN THE 1920S Joseph F. Clark, III Ninety years ago, America was a very different place, but still similar to the America of today in many ways. Immediately following World War I, a large number of veterans returned from overseas unable to fmd suitable work. A popular song of the time by Tin Pan Alley asked the question, "How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm, After They've Seen Paree?" Indeed, many of the veterans did not return to their family farms, choosing instead to move to nearby smaller towns and cities. As President Woodrow Wilson's administration was winding down, many questioned the state of the economy and future of the nation. Shortly after the war, the country remained in a recession until 1921. As time passed, there was a move to entrepreneurism throughout many fmancial sectors. When Warren G. -

VA Vol 10 No 1 Jan 1982

STRAIGHT AND LEVEL By Brad Thomas President Antique/Classic Division Happy New Year! We truly hope each member of the of museum visitors. Also on display is our "Wall of Fame" Antique/Classic Division had a successful and outstanding project that is under the direction of Division Advisor, year in 1981. At the completion of a calendar year we Ed Burns. Here recognition is given to our Division always look back to see what we have accomplished; members, their restoration projects and significant and then we look forward to the new year with a set historical subjects. Past antique and classic grand ofresolutions to abide by. champions are included in this display to bring to the Scanning 1981, we had been faced with enormous attention of the visitors. increases in the costs of sport flying. Fuel costs were E. E. "Buck" Hilbert, past Division President and still rising, student pilot starts were decreasing and current Treasurer volunteered to chair the research pleasure flights were curtailed or eliminated in order to and historic committee of the Antique/Classic Division. attend a choice of fly-ins. Of utmost importance, this venture will retain for There is always a driving element that rejects the posterity the history and persons who have so dedicated computer statistics thrust at us. That element is the themselves to the advancement of our Division. desire to accomplish a goal regardless of the obstacles. Communications to our membership has been and This became evident in the spring of 1981 when EAA will be continued through The VINTAGE AIRPLANE. Antique/ Classic Chapter 3 held its largest and most Reports of our Division functions, restoration articles, successful spring fly-in at Burlington, North Carolina.