The Current: Balancing Localism in Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN BASIC PLAN (Rev

City of Apple Valley EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN BASIC PLAN (rev. 0) CITY OF APPLE VALLEY EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN Effective Date January 1, 2017 Apple Valley – Emergency Operations Plan Basic Plan–i City of Apple Valley EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN BASIC PLAN (rev. 0) FOREWARD The purpose of this plan is to provide a guide for emergency operations. The plan is intended to assist city officials and emergency organizations to carry out their responsibilities for the protection of life and property under a wide range of emergency conditions. This plan is in accordance with existing federal, state, and local statues and understandings of the various departments/agencies involved. It has been adopted by the city council and reviewed by the Dakota County Emergency Management Director. It is subject to review and recommendation of approval by the Minnesota Department of Public Safety, Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management and the Metro Regional Review Committee (RRC). This plan is to be reviewed and re-certified annually by the City’s Emergency Management Director. All recipients are requested to advise the City’s Emergency Management Director of any changes that might result in its improvement or increase its usefulness. This document will serve to provide documentation of the knowledge of key individuals and can be used to inform persons who become replacements. "This Emergency Operations Plan shall not be shared or disclosed to any person or agency outside of the City of Apple Valley that do not have direct responsibilities to implement the Plan.” The data in this Emergency Operations Plan is not public data and shall not be disclosed. -

2016 ARRL Boxboro Info for Parents.Pages

The ARRL New England Convention at the Holiday Inn, Boxborough, MA September 9-10-11, 2016 Friday Evening DXCC Dinner Saturday Evening Banquet Keynote Speaker David Collingham, K3LP Keynote Speaker Historian Donna Halper The VP8S South Sandwich & South Georgia Heroes of Amateur Radio, Past, Present, and DXpedition Future Social Hour 6PM, Dinner 7PM Social Hour 6PM, Dinner 7PM David Collingham, K3LP, was a co-leader of the fourteen Donna Halper is a respected and experienced media member team that visited South Sandwich and South historian, her research has resulted in many Georgia Islands in February 2016 to put VP8STI & appearances on both radio and TV, including WCVB's VP8SGI on the air. David has participated in dozens of Chronicle, Voice of America, PBS/NewsHour, National DXpeditions as noted on his K3LP.COM website. He will Public Radio, New England Cable News, History be sharing his experiences from his last one with us. Channel, ABC Nightline, WBZ Radio (Boston) and many more. She is the author of six books, including Boston Radio 1920 - a history of Boston radio in words and pictures. Ms. Halper attended Northeastern University in What is the ARRL Boxboro Convention? Boston, where she was the first woman announcer in the school's history. She turned a nightly show in 1968 on The ARRL (American Radio Relay League), a the campus radio station into a successful career in national organization for amateur radio, hosts ham broadcasting, including more than 29 years as a radio conventions across the US each year. Held at the programming -

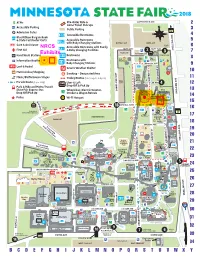

Natural Resources Conservation Service

2018 $ ATMs Pre-Order Ride & LARPENTEUR AVE Game Ticket Pick Ups Accessible Parking Public Parking # Admission Gates Accessible Restrooms Blue Ribbon Bargain Book & State Fair Poster Carts Accessible Restrooms with Baby Changing Stations BUFFALO LOT CAMEL LOT Care & Assistance Bicycle NRCS Accessible Restrooms with Family Lot First Aid HOYT AVE HOYT AVE AVE SNELLING & Baby Changing Facilities Metro TIGER LOT Mobility 3 ROOSTER LOT Drop Hand Wash StationsExhibits Restrooms Campground Expo The Pet Place X-Zone Information Booths Restrooms with Pavilions Baby Changing Stations MURPHY AVE Lost & Found SkyGlider Severe Weather Shelter $ Merchandise/Shopping Smoking – Designated Area Music/Performance Stages Giant Trolley Routes ( a.m.- p.m., p.m.) Sing OWL Along $ ST COSGROVE Parade Route ( p.m. daily) Uber & Lyft LOT Old Iron Show ST COOPER LEE AVE 4 Park & Ride and Metro Transit Drop O & Pick Up State Fair Express Bus Wheelchair, Electric Scooter, WAY ELMER DAN Eco UNDERWOOD ST UNDERWOOD Little Experience Drop O/Pick Up Stroller & Wagon Rentals Farm Progress AVE SNELLING Hands The Center North Police Wi-Fi Hotspot Woods B $ U Laser Encore’s F Laser Hitz O RANDALL AVE 18 Show R Bicycle Math D Lot RANDALL AVE On-A-Stick Fine Pedestrian & Arts Service Vehicle Entrance Center Great Family Fair Big Wheel CHARTER BUSES Baldwin ROBIN LOT Park Alphabet -H Forest Building WRIGHT AVE Park &Transit Ride Buses Hub $ Education Building SNELLING AVE SNELLING Horton ST COOPER Cosgrove Pavilions Kidway Home ST COSGROVE Stage Transit Hub at Heron Improvement Express Buses Park Building Grandstand Schilling $ $ Plaza & Amphitheater $ Ticket Oce Creative Elevator ST UNDERWOOD Activities History & 16 Elevator Buttery Visitors & Annex Heritage $ Grandstand SkyGlider House $ Plaza Center The Veranda $ DAN PATCH AVE $ West End $ U of M $ Market $ The MIDWAY $ FAN Garden Merchandise PARKWAY Skyride Health Central Fair 11 Mart WEST DAN PATCH AVE Ramp Carousel Libby Conf. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

I STRUCTURAL MODEL of KNOWLEDGE ELEMENTS

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Institutional Repository i STRUCTURAL MODEL OF KNOWLEDGE ELEMENTS, MEDIATING CONSTRUCTS AND PERFORMANCE FOR FACILITIES MANAGEMENT ORGANISATION AHMAD FIRDAUZ BIN ABDUL MUTALIB A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Facilities Management) Faculty of Geoinformation and Real Estate Universiti Teknologi Malaysia AUGUST 2016 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The most , ﷲ First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest thanks to gracious and most merciful God for the blessing, wisdom, health, strength and patience that He gave upon me throughout this adventurous, exciting and challenging PhD journey. This journey will not be a dream come true without these two intellectual people who have been patiently, supportively and continuously encouraging me to keep on working hard to complete this thesis. From the bottom of my heart, I would like to express my profound appreciation to my main supervisor, Prof. Madya Dr. Maimunah Sapri, for her insights, words of encouragement and the belief she always had in me; and also my co-supervisor, Prof. Madya Dr. Hj. Ibrahim Sipan. Their generosity and patience to review, comment, and give thoughtful suggestions to improve this thesis. I am forever grateful and thankful to have met and been given the opportunity to work with both of them. My sincere gratitude goes to Jabatan Perkhidmatan Awam and Jabatan Kerja Raya Malaysia for giving me this opportunity and providing me with the financial support. Saving the best for last, to my dearest wife and sweetheart – Noor Faaizah; “Thank you for being beside me throughout these years. -

Live Oak Banking Company 2605 Iron Gate Dr, Ste 100 2013 7(A) Jpmorgan Chase Bank, National 1111 Polaris Pkwy 2013 7(A) U.S

APPVFY MAJPGM L2Name L2Street 2013 7(A) Wells Fargo Bank, National Ass 101 N Philips Ave 2013 7(A) Live Oak Banking Company 2605 Iron Gate Dr, Ste 100 2013 7(A) JPMorgan Chase Bank, National 1111 Polaris Pkwy 2013 7(A) U.S. Bank National Association 425 Walnut St 2013 7(A) The Huntington National Bank 17 S High St 2013 7(A) Ridgestone Bank 13925 W North Ave 2013 7(A) Seacoast Commerce Bank 11939 Ranho Bernardo Rd 2013 7(A) Wilshire State Bank 3200 Wilshire Blvd, Ste 1400 2013 7(A) Compass Bank 15 S 20th St 2013 7(A) Hanmi Bank 3660 Wilshire Blvd PH-A 2013 7(A) Celtic Bank Corporation 268 S State St, Ste 300 2013 7(A) KeyBank National Association 127 Public Sq 2013 7(A) Noah Bank 7301 Old York Rd 2013 7(A) BBCN Bank 3731 Wilshire Blvd, Ste 1000 2013 7(A) TD Bank, National Association 2035 Limestone Rd 2013 7(A) Manufacturers and Traders Trus One M & T Plaza, 15th Fl 2013 7(A) Newtek Small Business Finance, 212 W. 35th Street 2013 7(A) SunTrust Bank 25 Park Place NE 2013 7(A) Hana Small Business Lending, I 1000 Wilshire Blvd 2013 7(A) First Bank Financial Centre 155 W Wisconsin Ave 2013 7(A) NewBank 146-01 Northern Blvd 2013 7(A) Open Bank 1000 Wilshire Blvd, Ste 100 2013 7(A) Bank of the West 180 Montgomery St 2013 7(A) CornerstoneBank 2060 Mt Paran Rd NW, Ste 100 2013 7(A) Synovus Bank 1148 Broadway 2013 7(A) Comerica Bank 1717 Main St 2013 7(A) Borrego Springs Bank, N.A. -

Ii~I~~111\11 3 0307 00072 6078

II \If'\\II\I\\OOI~~\~~~II~I~~111\11 3 0307 00072 6078 This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Senate Rule 71. Provision shall be made for news reporters on the Senate floor in limited numbers, and in the Senate gallery. Because of limited space on the floor, permanent space is I limited to those news agencies which have regularly covered the legislature, namely: The Associated Press, St. Paul Pioneer Press, Star Tribune, Duluth News-Tribune, Fargo Forum, Publication of: Rochester Post-Bulletin, St. Cloud Daily Times, WCCO radio, KSTP radio and Minnesota Public Radio. -An additional two The Minnesota Senate spaces shall be provided to other reporters if space is available. Office of the Secretary of the Senate ~ -:- Patrick E. flahaven One person Jrom each named agency and one person from the 231 State Capitol Senate Publications Office may be present at tbe press table on St. Paul, Minnesota 55155 the Senate floor at anyone time. (651) 296-2344 Other news media personnel may occupy seats provided in the Accredited through: Senate gallery. Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Sven lindquist The Committee on Rules and Administration may, through Room 1, State Capitol committee action or by delegating authority to the Secretary, St. Paul, Minnesota 55155 allow television filming on the Senate floor on certain occasions. (651) 296-1119 The Secretary of the Senate shall compile and distribute to the This publication was developed by the staff of public a directory of reporters accredited to report from the Senate Media Services and Senate Sergeant's Office Senate floor. -

Profil Syarikat

Raja Segala Herba PROFIL SYARIKAT SeraiMas Herbs Sdn Bhd (1227131-D) No 20, Industri Ringan, Teres 3 Tingkat, Jalan Teguh 2, Taman Perindustrian Labis, 85300 Labis, Johor. t : +6019 810 8634 w : www.SeraiMas.my TENTANG KAMI SeraiMas Herbs Sdn Bhd memulakan langkah pada penghujung tahun 2005. Seraimas merupakan syarikat yang dimiliki sepenuhnya oleh pemilik bumiputera. Kualiti produk dan kepuasan pengguna menjadi visi utama syarikat untuk lebih maju ke hadapan. “Kepuasan pelanggan keutamaan kami” PUAN SUNITA ALI AKHBAR PENGASAS TENTANG KAMI MISI Syarikat kami memasarkan produk yang diiktiraf dan terbukti berkesan dengan lebih SeraiMas Herbs Sdn Bhd memulakan langkah pada penghujung tahun satu juta pengguna dalam membawa kembali pengalaman khasiat herba semulajadiuntuk 2005. Seraimas merupakan syarikat yang dimiliki sepenuhnya oleh membantu meningkatkan taraf kesihatan pemilik bumiputera. Kualiti produk dan kepuasan pengguna menjadi dan memberi kesedaran mengenai kepentingan penjagaan kesihatan kepada seluruh visi utama syarikat untuk lebih maju ke hadapan. keluarga di Malaysia. “Kepuasan pelanggan keutamaan kami” VISI PUAN SUNITA ALI AKHBAR PENGASAS PUAN MARLINDA JASRIZAL PENGURUS BESAR NILAI BERSAMA LOVING OPTIMISM VISIONARY ENTHUSIASM SINCERE PENSIJILAN JABATAN KEMAJUAN ISLAM MALAYSIA NILAI BERSAMA (HALAL) LOVING OPTIMISM VISIONARY ENTHUSIASM SINCERE HAKMILIK SERAIMAS HERBS SDN BHD PENSIJILAN JABATAN KEMAJUAN ISLAM MALAYSIA (HALAL) HAKMILIK SERAIMAS HERBS SDN BHDHAKMILIK SERAIMAS HERBS SDN BHD Scanned with CamScanner PENSIJILAN PENSIJILAN -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018. -

Why Fund Ampers?

What is Ampers? • An association of 18 independent community radio stations. • Each station is locally managed and programmed by and for their communities. • Stations create their own programming and do not rebroadcast programs from one main Twin Cities station. • The stations primarily serve rural, minority and student communities not served by traditional media with programming in 12 languages. • All are licensed as non-commercial educational stations. Why Fund Ampers? • Stations provide in-depth information about local government, educational and health news, safety concerns, and provide local artists access to the airwaves. • The stations are extremely efficient relying heavily on volunteers. • Ampers stations help to train more than 1,300 students each year. • Stations provide critical emergency information in some cases providing local officials with the only immediate opportunity to disseminate lifesaving information. A North High student announcing A band performs live from “Studio K” KSRQ’s “Saturday Morning Barn Dance” on KBEM/Jazz88 (produced by students) on Radio K What is the difference between Ampers and Minnesota Public Radio? There are two types of public radio in Minnesota, the Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) network and the smaller local community radio stations. The smaller grassroots community stations created the Association of Minnesota Public Education Radio Stations (Ampers) in 1972. KAXE’s “Ranger in My Heart,” a documentary on the Iron Range. The Ampers stations, Minnesota Public Radio, and Minnesota Public Television are not affiliated financially in any way other than the fact that all three receive state and federal funding because they are prohibited from selling commercials. Ampers MPR • An association of 18 independent • A network of regional radio stations locally programmed community radio stations. -

Chapter 11 ) CITADEL BROADCASTING CORPORATION, Et Al., ) Case No

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) CITADEL BROADCASTING CORPORATION, et al., ) Case No. 09-17442 (BRL) ) Debtors. ) Jointly Administered ) FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER CONFIRMING THE SECOND MODIFIED JOINT PLAN OF REORGANIZATION OF CITADEL BROADCASTING CORPORATION AND ITS DEBTOR AFFILIATES PURSUANT TO CHAPTER 11 OF THE BANKRUPTCY CODE The Second Modified Joint Plan of Reorganization of Citadel Broadcasting Corporation and its Debtor Affiliates Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, dated May 10, 2010, a copy of which is annexed hereto as Exhibit 1 and incorporated herein by reference (the “Plan”),1 having been filed with the Court by Citadel Broadcasting Corporation (“Citadel”) and its debtor affiliates, as debtors and debtors in possession (collectively, the “Debtors”);2 and the Court 1 Capitalized terms used but not otherwise defined herein shall have the meanings ascribed to such terms in the Plan. The Joint Plan of Reorganization of Citadel Broadcasting and Its Debtor Affiliates Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code was filed on February 3, 2010 [Docket No. 110]; the First Modified Joint Plan of Reorganization of Citadel Broadcasting and Its Debtor Affiliates Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code was filed on March 15, 2010 [Docket No. 198]. 2 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases are: Alphabet Acquisition Corp.; Atlanta Radio, LLC; Aviation I, LLC; Chicago FM Radio Assets, LLC; Chicago License, LLC; Chicago Radio Assets, LLC; Chicago Radio Holding, -

A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (Guest Post)*

“A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (guest post)* Garrison Keillor “Well, it's been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon, Minnesota, my hometown, out on the edge of the prairie.” On July 6, 1974, before a crowd of maybe a dozen people (certainly less than 20), a live radio variety program went on the air from the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, MN. It was called “A Prairie Home Companion,” a name which at once evoked a sense of place and a time now past--recalling the “Little House on the Prairie” books, the once popular magazine “The Ladies Home Companion” or “The Prairie Farmer,” the oldest agricultural publication in America (founded 1841). The “Prairie Farmer” later bought WLS radio in Chicago from Sears, Roebuck & Co. and gave its name to the powerful clear channel station, which blanketed the middle third of the country from 1928 until its sale in 1959. The creator and host of the program, Garrison Keillor, later confided that he had no nostalgic intent, but took the name from “The Prairie Home Cemetery” in Moorhead, MN. His explanation is both self-effacing and humorous, much like the program he went on to host, with some sabbaticals and detours, for the next 42 years. Origins Gary Edward “Garrison” Keillor was born in Anoka, MN on August 7, 1942 and raised in nearby Brooklyn Park. His family were not (contrary to popular opinion) Lutherans, instead belonging to a strict fundamentalist religious sect known as the Plymouth Brethren.