Modernism: in Print Dutch Graphic Design 1917—2017 O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vintage Posters

IN OUR TIME So far 2013 has been an exciting year at Swann. In January, a sale of illustration art and illustrated books established what will be a new department for us, while our reinstated Old Master Drawings auction drew crowds and much interest for a newly discovered J.M.W. Turner watercolor. February saw our best winter Vintage Posters auction ever, setting records for images by Art Nouveau master Alphonse Mucha, and love was in the air at our Valentine’s Day auction of African-American Fine Art, where paintings by Barkley L. Hendricks and Hughie Lee-Smith, as well as a sculpture by Elizabeth Catlett, achieved top-dollar results. We wrapped up the month with Fine Photographs, featuring early Asian travel albums and avant-garde modernist images, followed by scarce Early Printed Books. American and European artists divided the top lots at our March 7 Prints & Drawings auction, and the word of the day at our Writing Instruments sale was Montblanc, Montblanc, Montblanc. Looking ahead, May is a busy month full of intriguing offerings, including graphic design and typography from the inventory of the late Irving Oaklander, noted bookseller, followed by more scintillating design, typography and graphic art in our sale of modernist posters. Our Contemporary Art sale coincides with Frieze week in New York, and the month concludes with a diverse auction of Autographs. In early June a sale of Maps & Atlases offers rare items of American interest, and mid-month American Art features paintings and drawings by artists including Milton Avery, Robert Gwathmey and John Singer Sargent. -

Photo/Graphics Michel Wlassikoff

SYMPOSIUMS 1 Michel Frizot Roxane Jubert Victor Margolin Photo/Graphics Michel Wlassikoff Collected papers from the symposium “Photo /Graphisme“, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 20 October 2007 © Éditions du Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2008. © The authors. All rights reserved. Jeu de Paume receives a subsidy from the Ministry of Culture and Communication. It gratefully acknowledges support from Neuflize Vie, its global partner. Les Amis and Jeunes Amis du Jeu de Paume contribute to its activities. This publication has been made possible by the support of Les Amis du Jeu de Paume. Contents Michel Frizot Photo/graphics in French magazines: 5 the possibilities of rotogravure, 1926–1935 Roxane Jubert Typophoto. A major shift in visual communication 13 Victor Margolin The many faces of photography in the Weimar Republic 29 Michel Wlassikoff Futura, Europe and photography 35 Michel Frizot Photo/graphics in French magazines: the possibilities of rotogravure, 1926–1935 The fact that my title refers to technique rather than aesthetics reflects what I take to be a constant: in the case of photography (and, if I might dare to say, representation), technical processes and their development are the mainsprings of innovation and creation. In other words, the technique determines possibilities which are then perceived and translated by operators or others, notably photographers. With regard to photo/graphics, my position is the same: the introduction of photography into graphics systems was to engender new possibilities and reinvigorate the question of graphic design. And this in turn raises another issue: the printing of the photograph, which is to say, its assimilation to both the print and the illustration, with the mass distribution that implies. -

The Urban and Cultural Climate of Rotterdam Changed Radically Between 1970 and 2000. Opinions Differ About What the Most Importa

The urban and cultural climate of Rotterdam changed radically between 1970 and 2000. Opinions differ about what the most important changes were, and when they occurred. Imagine a Metropolis shows that it was first and foremost a new perspective on Rotterdam that stimulated the development of the city during this period. If the Rotterdam of 1970 was still a city with an identity crisis that wanted to be small rather than large and cosy rather than commercial, by 2000 Rotterdam had the image of the most metropolitan of all Dutch cities. Artists and other cultural practitioners – a group these days termed the ‘creative class’ – were the first to advance this metropolitan vision, thereby paving the way for the New Rotterdam that would begin to take concrete shape at the end of the 1980s. Imagine a Metropolis goes on to show that this New Rotterdam is returning to its nineteenth-century identity and the developments of the inter-war years and the period of post-war reconstruction. For Nina and Maria IMAGINE A METROPOLIS ROTTERDAM’S CREATIVE CLASS, 1970-2000 PATRICIA VAN ULZEN 010 Publishers, Rotterdam 2007 This publication was produced in association with Stichting Kunstpublicaties Rotterdam. On February 2, 2007, it was defended as a Ph.D. thesis at the Erasmus University, Rotterdam. The thesis supervisor was Prof. Dr. Marlite Halbertsma. The research and this book were both made possible by the generous support of the Faculty of History and Arts at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, G.Ph. Verhagen-Stichting, Stichting Kunstpublicaties Rotterdam, J.E. Jurriaanse Stichting, Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds Zuid-Holland and the Netherlands Architecture Fund. -

AVANT-GARDES: Selections from the Merrill C

F O R I M M E D I A T E R E L E A S E AVANT-GARDES: Selections from the Merrill C. Berman Collection February 5 – April 24, 2004 Constructivism, Dada, De Stijl, Futurism, Neue Sachlichkeit, Surrealism J. S. Anderson, Johannes Baader, Willi Baumeister, Christ Beekman, Pasqualinio Cangiullo, Carlo Carrà, Jean Crotti, Felix DeBoeck, Walter Dexel, Cesar Domela, Vassily Ermilov, Alexandra Exter, George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Karl Holtz, Vilmos Huszar, Paul Joostens, Gustav Klutsis, El Lissitzky, Lou Loeber, Jeanne Mammen, Robert Michel, Alastair Morton, Oskar Nerlinger, Josef Peeters, Liubov Popova, Thijs Rinsema, Aleksandr Rodchenko, Karl Peter Röhl, Rudolf Schlichter, Paul Schuitema, Victor Servranckx, Nikolai Sidelnikov, Maria Siniakova, Jindrich Styrsky, Karel Teige, Solomon Telingater, Jan Tschichold, L. H. Tutundjian, Konstantin Vialov, Ilia Zdanevitch, Piet Zwart Ubu Gallery is pleased to present AVANT-GARDES: Selections from the Merrill C. Berman Collection, featuring more than 65 works by over 40 artists associated with most of the major European avant-garde movements which flourished between the two World Wars. Selected from his superb collection by Merrill Berman himself, this exhibition presents a richly diverse group of artists and styles linked by their “forward- looking” posture and visual “punch.” The works to be exhibited at Ubu – as with Berman’s entire collection – represent a “personalized” cut through 20th Century visual culture “authored” by a collector with an extremely keen and knowledgeable eye. Rather than acquiring only important names (although the collection has more than its share of these, as well), Berman has considered the “aesthetic” aspect of each work and its historical context in deciding whether to add it to his collection. -

SURVEY 9: COLOUR THEORY and COOL TYPE (1925-1930) 9 Art Deco, the Bauhaus, Jan Tschichold and the Leap Forward Into Modern Typography

SURVEY 9: COLOUR THEORY AND COOL TYPE (1925-1930) 9 Art Deco, the Bauhaus, Jan Tschichold and the leap forward into modern typography. What world events influenced design in this period? Gropius’s objective for the school was a radical concept: In 1925, 25,000 Ku Klux Klansmen marched on Wash- to reimagine the material world to reflect the unity of all ington. First founded in 1865, the KKK was a national the arts. Fine art, design of all kinds and craftsmanship fraternal organization founded on the premise of white were taught in unison using hands-on techniques. The supremacy. The power of the Klan peaked during the Bauhaus went on to have a profound impact on all fields 1920s when urbanization, industrialization, and immigra- of art and design across the world, both through its teach- tion frightened many Americans. ing methods and its famous graduates. Some graduates and instructors spread the Bauhaus ethos to the U.K. In 1928, 15 nations, including the United States, signed and the U.S., as they fled the Nazi regime in the 1930’s. the Kellogg-Briand pact “outlawing” war. The unenforce- Likely influenced by Gropius’s (and fellow architect able pact was made a mockery of by the rise of European Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s) involvement in Hermann fascist states in the 1930s. Muthesius’s Deutscher Werkbund—which continued to In 1929, Canadian women were granted the right to be operate until 1933—the Bauhaus fostered relationships considered “persons.” Canada’s first female magistrate, between crafts and industry in order to bring good design Emily Murphy, was humiliated while hearing her first to the masses. -

Cjvof'u.C Tevct~Oy~Ts- ,"Y,'R, ~\\ '6 I

• CjVOf'u.c tevct~oy~ts- ,"y,'r, ~\\ '6 i Check List of THE GRAPHIC REVOLUTION: 1915-1935 3 Wall labels Title of show in wooden letters MoMAExh_1182_MasterChecklist , ..Lab e L' No. 1. EL LISSITZKY Russian, 1890-1941 Poster for a Russian exhibition in Zurich, 1929. 2. 2 LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY Hungarian, 1895-1946 The Eyernal Feminine, photomontage c. 1925 Given anonymously 3. 3 LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY Hungarian, 1895-1946 MoMAExh_1182_MasterChecklist Love Thy Neighbour, photomontage 1925 Given anonymously 4. 4 LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY Hungarian, 1895-1946 Militarism, photomontage 1924 Given anonymously 5. 5 LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY Hungarian, 1895-1946 Dream of School Girls, photomontage 1924 Given anonymously 6. 6 LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY Hungarian, 1895-1946 Structure of the World, photomontage 1926 Given anonymously 7. 7 LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY Hungarian, 1895-1946 Chute, photomontage, 1923 Gift of Mrs. Sibyl Moholy-Nagy 8. 8 LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY Hungarian, 1895-1946 Double-page spread from his book "Painting, Photography, Film," number 8 of the Bauhaus Books. Munich, 1925. 9. 9 LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY Hungarian, 1895-1946 Front cover for a brochure advertising the fourteen Bauhaus Books. Munich, 1928 Label NC!>. 10. 10 HERBERT DIIYEI( Austrian, born 1900 Invitation to the Beard, Nose, and Heart Festival at the Bauhaus. Dessau, 1928 11. 11 ALBRECHT HEUBNER German, dates unknown Four studies in thematic and optic contrasts. Dessau, c. 1928. These are exercises for Joost Schmidt's Typography and Layout Class of the Bauhaus, in which the artist was a pupil. 12. 12 ALBRECHT HEUBNER German, dates unknown "Attention." photomontage, made at the Bauhaus. MoMAExh_1182_MasterChecklist Dessau, c. -

CHICAGO ART DECO SOCIETY Tviagazine

SPRING I SUMMER 2019 CHICAGO ART DECO SOCIETY tviAGAZINE IN TI-llS ISSUE: Who l:lse Can Swing from the Siegfried Line to the New l-lipline? Lee Miller's WWII Articles for Vogue Architecture Though the Lens: A New Way of Picturing the 1930s The Influence of Photography on l=ernand Leger as Painter and l=ilmmaker A New Life for a Cincinnati Art Deco: Photo l:ssay Jan Tschichold and the New Typography: Graphic Design Between the World Wars LARA ALLISON New Typography, in 1928. Tschichold's handdrawn illustrations, and activation of training in the traditional graphic arts of white space-played themselves out most calligraphy made him well-equipped to gauge fully. As an essential feature of the modern Image (above): Kurt Schwitters. 6 Punkte the radical aspects of what Laszlo Moholy condition within a capitalist society, advertising bildendie Vorzuge der Stopfbuchslosen, Nagy dubbed "the New Typography" in 1923. offered the context best matched to the Rheinhiitte Saurepumpen, Weise Sohne, goals of the New Typography. In the words of Halle/S (Six points create advantages for ... Although it was a young Tschichold's visit to German graphic designer Johannes Molzahn, acid pumps, Weise Sons, Halle/Saale) brochure, the 1923 Bauhaus exhibition that inspired (or, "Increasingly, production and sales must... ca. 1927. Letterpress. 7he Museum ifModern in his words, "agitated") him to explore the demand the creation of advertising according Art, New York,]an Tschichold Collection, Gift depth and breadth of new currents in graphic ifPhil ip johnson, 925.1999. Digital Image to the principles that apply to the entire © 1he Museum ifModern Art/Licensed by design, the Bauhaus itself plays a limited role operating process: to achieve the maximum SCALA I Art Resource, m © 2018 Artist in the Bard exhibition. -

A CONFERENCE on READING and PUBLISHING in the DIGITAL AGE Amsterdam & Den Haag 19-21 May Program Page Introduction

www.e-boekenstad.nl/unbound A CONFERENCE ON READING AND PUBLISHING IN THE DIGITAL AGE Amsterdam & Den Haag 19-21 May PROGRAM PAGE INTRODUCTION THURSDAY, MAY 19 Pre-day Workshops 02 HOGESCHOOL VAN AMSTERDAM THE UNBOUND 11.00 – 13.30 Open Publishing Tools 03 13.30 – 14.00 Lunch BOOK 14.00 – 17.00 Digital Enclosures 03 14.00 – 17.00 E-readers in Dutch Education (RAAK Session) 03 17.00 – 18.00 Food and Drinks A THREE-DAY INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LITERACY AND PUBLISHING IN THE DIGITAL AGE FRIDAY, MAY 20 The conventional notion of the book, based on centuries of print, has rapidly grown outdated. Meanwhile the capacity Conference Day One 04 AULA ROOM, KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK (KB), to create digital book-like functions and forms is endless. DEN HAAG In a double sense the book is coming unbound, both from the bindings of the printed volume and also the boundaries 09.30 – 10.00 Doors Open, Coffee and Tea between multimedia content and modes of authorship in a 10.00 – 10.15 Opening Remarks by Joost Kircz vast, interconnected electronic space. 10.15 – 12.30 Session One: What is a Book? 05 12.30 – 13.30 Lunch These possibilities may be exciting, but the digital book is left 13.30 – 15.30 Session Two: The Unbound Book 06 without obvious contours. The entire concept of ‘bookness’ 15.30 – 15.45 Coffee and Tea Break needs reinvention. To do this well, we must go back to the 15.45 – 17.30 Session Three: Ascent of E-readers 08 basics. -

Audio Tour Transcript

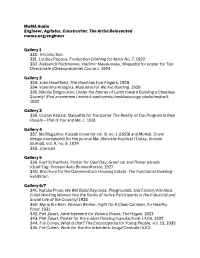

MoMA Audio Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented moma.org/engineer Gallery 1 330. Introduction 331. Lyubov Popova, Production Clothing for Actor No. 7, 1922 332. Aleksandr Rodchenko, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Maquette for poster for Tea Directorate (Chaeupravlenie) Cocoa c. 1924 Gallery 2 333. John Heartfield, The Hand has Five Fingers, 1928 334. Valentina Kulagina, Maquette for We Are Building, 1929 335. Nikolai Dolgorukov, Under the Banner of Lenin toward Building a Classless Society! (Pod znamenem Lenina k postroeniiu besklassovogo obshchestva!), 1932 Gallery 3 336. Gustav Klutsis, Maquette for the poster The Reality of Our Program Is Real People—That Is You and Me, c. 1931 Gallery 4 337. Ma Magazine: Kassak cover for vol. 9, no. 1 (1923) and Molnár, Cover design (unrealized) for the journal Ma: Aktivista-folyóirat (Today: Activist journal), vol. 9, no. 5, 1924 338. Journals Gallery 5 339. Kurt Schwitters, Poster for Opel Day: Great car and flower parade (Opel-Tag: Grosser Auto BlumenKorso), 1927 340. Brochure for the Dammerstock Housing Estate: The Functional Dwelling Exhibition Gallery 6/7 341. Natalia Pinus, We Will Build Daycares, Playgrounds, and Factory Kitchens. Enlist Working Women into the Ranks of Active Participants in the Industrial and Social Life of the Country! 1933 350. Maria Bri-Bein, Woman Worker, Fight for A Clean Canteen, for Healthy Food, 1931 342. Piet Zwart, Advertisement for Vickers House, The Hague, 1923 343. Piet Zwart, Poster for the rubber flooring manufacturer LAGA, 1922 344. Fré Cohen, What is that? The Encyclopedia for Young People, vol. 13, 1935 345. Fré Cohen, Work for the the Arbeiders-Jeugd Centrale (AJC) Gallery 8 346. -

Notes and News TIDINGS from the BOARD Dr. Albert Derolez, A

Notes and news TIDINGSFROM THE BOARD Dr. Albert Derolez, a member of our Advisory Board, was appointcd in October 1972 to an Extraordinary Professorship at the Free University of Brussels,where he is now giving a course of lectures on Codicology and Miniatures. His inaugural lecture dealt with Codicology and Cultural History, and will be published shortly in the Journal of the Free Univcrsity. Albert Derolez was born in Blankenberge, Belgium, in 1934. In 1970 he took his doctorate in history, his thesis being entitled 'De Liber Floridus-autograaf (cod. Gand. 92). Een codicolo- gische studie'. Since 1962 he has been in charge of the Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books of the University Library of Ghent, where he is also director of the restoration workshop. Derolez's interest is directed principally at the medieval libraries, especially those of the Low Countrics, and their catalogues, though at thc same time he is interested in the more limited branches of codicology, such as the archaeological study of medieval manuscripts and their various characteristics. It is largely in this field, indeed, that Derolez's publications are to be found. Of these we may mention here De rniddeleeuwsebibliotheekgeschiedcnis. Opgaven, bronnen en stand van het onderzoek,in: Bibliotheekgids, 40 (1964), pp. 33-46; Census van de handschriften van deBibliotheek der RyksuniversiteitGent, VI. Ghent 1964, 64 pp. ; Corpus catal(?qortilliBelgii. De rniddelecuUJsebibliotheekscatalogi der Zi.iidehke Nederlanden,the first volume of which, dealing with the province of West Flanders, appeared in 1966. In the same year, together with E. I. Strubbe, Derolez completed the monumental edition of thc Liber Floridus: Lambertus S. -

Piet Zwart Typotekt June1-July8 2014 Typographer Architect

piet zwart Memphis Film Piet Zwart was a Dutch archi- Since Zwart was a self- & Television tect who was noted mostly by thought typographer, he of- and AVRO his avant-garde approaches ten didn’t pay close attention invite graphic in modern typography and to typographic details, such designers to design. His contemporary as differentiating of upper design a film typotekt designs were of a similar cali- and lower case; instead, the poster for Ev- ber to the work and innova- way he assembled symbols, erything Must tion of the Bauhaus. He was negative space, and letters Change – Piet deeply influenced by De Stijl, gave his unusual dynamic Zwart. The new Russian Constructivism and compositions. Indeed, Zwart film by direc- Dada art movement. Zwart learned the basics of type and tor Sherman never believed in belonging printing from an 18-year-old De Jesus tells to a particular artistic move- apprentice. Later, working for typographer the story of the ment so he absorbed the best NKF Company, he mastered progressive ideas of these three art styles these basic methods of typog- and innovative and broke apart to create his raphy while founding a new designer Piet own work. Zwart referred to style with the use of primary Zwart. architect himself as ‘Typotekt,” a hybrid colors and photomontage. In- of the words “typographer” spired by Bauhaus professor and “architect,” as he devel- László Moholy-Nagy in the oped new designs that were late 1920’s and early 1930’s, built with typography. Zwart’s he increasingly focused in first typographical work in- photography. -

Mechanics and Expression: Franz Roh and the New Vision — a Historical Sketch

Mechanics and Expression: Franz Roh and the New Vision — A Historical Sketch Inka Graeve Ingelmann Photo-eye is a nervous and important book. Its editors call the world not only beautiful but exciting, cruel, and weird. In intention social and didactic, this is an anthology of the “new” photography; yet its editors knew where to look for their material. — Walker Evans,“The Reappearance of Photography,” 19311 Foto-auge (Photo-eye) was one of the most influential publi- cations in the field of the New Photography in the 1920s (fig. 1). Shortly after its appearance it was euphorically celebrated as a “culturally pioneering work,” as a “collection of disturb- ingly beautiful pictures,” and as an “art history of modern photography,” and it took first place among the fifty most beautiful books of 1929.2 This compendium was conceived after a visit by Franz Roh, an academically trained art critic and champion of modern photography living in Munich, and the typographer Jan Tschichold, who was teaching in Munich, to the Stuttgart film and photography exhibition Film und Foto, known as Fi/Fo,3 from which most of its photographs were taken. Roh contributed the programmatic text “Mechanismus und Ausdruck” (Mechanism and expression), and Tschichold was responsible for the cover design and typography. Together they made the picture selection, a distillation from the more than one thousand works in the exhibition. Foto-auge contains seventy-six reproductions reflect- ing the entire range of the Neues Sehen (New Vision), and formulates the new photographic aesthetic that had estab- lished itself as the way of the future around 1929.