94 Nesian Styles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CASH BOX (ISSN 0008-7289) Is Published Mississippi Mass Choir Weekly (Except Cbrishias Holidays) by Cash (LIBERTY) (MALACO) News 3 Box, 1 57 W

/i triean •"# m v? W Banehkind Jjki: CJiirll: Hosis Aijuj'/ersary Sped-j] STAFF BOX GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher KEITH ALBERT CftStt Vice President/General Manager FRED L. GOODMAN Editor In Chief CAMILLE COMPASIO Director, Coin Machine Operations LEEJESKE New York Editor THE MUSIC TRADE MAGAZINE MARKETING LEON BELL Director, Los Angeles MARK WAGNER Director, Nashville KEN PIOTROWSKI (LA) EDITORIAL RANDY CLARK, Assoc. Ed. (LA) INSIDE THE BQX BRYAN DeVANEY, Assoc. Ed. (LA) BERNETTA GREEN (New York) COVER STORY STEVE GIUFFRIDA (Nashville) CORY CHESHIRE, Nashville Editor American BandstandTurns 40! GFEGORY S COOPER-Gospe((Nashvte) American Bandstand, the seminal rock 'n' roll dance show that debuted CHART RESEARCH CHERRY URESTI (LA) in 1952, will celebrate its anniversary with a star-studded television RAYMOND BALLARD (LA) MIA TROY (LA) special this week. Host Dick Clark will be joined by over 200 enter- COREY BELL (LA) JOHN GILLEN (LA) tainers, both Hive” and on tape, for the festivities. A salute to Clark is JOHN COSSIBOOM (Nash) CHRIS BERKEY (Nash) also included. PRODUCTION —see page 8 JIM GONZALEZ Art Director CIRCULATION L.A. Retailers React To Riot Losses NINATREGUB, Manager CYNTHIA BANTA The world will not soon forget the horrendous riots that ripped L.A. PUBLICATION OFFICES apart last week, as many stores were destroyed by looting and arson. NEW YORK 157 W.57th Street (Suite 503) New Record retailers, mostly chains, were unfortunately included in the Yoik, NY 10019 Phone: (212) 586-2640 devastation. M.R. Martinez reports on the damage, and looks to the Fax: (212) 582-2571 HOLLYWOOD V future. -

En Vogue L at Oya C R O S S

- Left to Right: Tem inimus sequiae veriatem quam, estibus amet et aborerro offici de rest, quam, tendand uscienti ut FROM QUARTET TO TRIO, THE FUNKY DIVAS STILL SHOW (AND PROVE) THEY WERE BORN TO SING :EN VOGUE L AT OYA C R O S S APRIL/MAY 2017 EBONY.COM 83 lion YouTube views. But wait, there’s connection that goes into play when to learn each of more: The sultry songstresses climbed blending voices, one that Bennett came En Vogue members, from left, Rhona Bennett, the girls and re- the charts six times with singles “Hold equipped with, Ellis explains. Terry Ellis and Cindy Herron-Braggs spect the difer- On,” “My Lovin’ (Never Gonna Get “It’s being conscious of each other ences,” says El- It),” “Free Your Mind,” “Giving Him when we’re singing,” she says. “Where lis, the youngest THE SUPREMES.The Marvelettes. Something He Can Feel,” “Don’t Let is she placing her vibrato? What’s the of fve siblings. The Pointer Sisters. Between the 1960s Go,” and “Whatta Man” featuring tempo or how is she executing this song, “For me, that’s and the 1980s, the music scene was Salt-N-Pepa. this line or this word? I never thought freeing your dominated by timeless female groups. On top of their silky siren abilities, about it, but maybe that does come with mind. I think the But when it comes to girl group dynam- pop culture embraced the clingy red some seasoning and time. Rhona is a key is to under- ics, the 1990s are defned by En Vogue— dresses the vocally gifed women se- veteran as well, so she came in with that stand that you a foursome equipped with efortless duced viewers with in the music video information and awareness already. -

Annual Report 2009-2010 PDF 7.6 MB

Report NZ On Air Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2010 Report 2010 Table of contents He Rarangi Upoko Part 1 Our year No Tenei Tau 2 Highlights Nga Taumata 2 Who we are Ko Matou Noa Enei 4 Chair’s introduction He Kupu Whakataki na te Rangatira 5 Key achievements Nga Tino Hua 6 Television investments: Te Pouaka Whakaata 6 $81 million Innovation 6 Diversity 6 Value for money 8 Radio investments: Te Reo Irirangi 10 $32.8 million Innovation 10 Diversity 10 Value for money 10 Community broadcasting investments: Mahi Whakapaoho a-Iwi 11 $4.3 million Innovation 11 Diversity 11 Value for money 11 Music investments: Te Reo Waiata o Aotearoa 12 $5.5 million Innovation 13 Diversity 14 Value for money 15 Maori broadcasting investments: Mahi Whakapaoho Maori 16 $6.1 million Diversity 16 Digital and archiving investments: Mahi Ipurangi, Mahi Puranga 17 $3.6 million Innovation 17 Value for money 17 Research and consultation Mahi Rangahau 18 Operations Nga Tikanga Whakahaere 19 Governance 19 Management 19 Organisational health and capability 19 Good employer policies 19 Key financial and non financial measures and standards 21 Part 2: Accountability statements He Tauaki Whakahirahira Statement of responsibility 22 Audit report 23 Statement of comprehensive income 24 Statement of financial position 25 Statement of changes in equity 26 Statement of cash flows 27 Notes to the financial statements 28 Statement of service performance 43 Appendices 50 Directory Hei Taki Noa 60 Printed in New Zealand on sustainable paper from Well Managed Forests 1 NZ On Air Annual Report For the year ended 30 June 2010 Part 1 “Lively debate around broadcasting issues continued this year as television in New Zealand marked its 50th birthday and NZ On Air its 21st. -

Forever My Lady Album

Forever my lady album click here to download Album[edit]. Chart (), Peak position. U.S. Billboard , U.S. Heatseekers, 1. U.S. R&B Albums, 1.Release and reception · Track listing · Personnel · Charts. Includes FREE MP3 version of this album. Provided by Amazon Digital This item:Forever My Lady by Jodeci Audio CD $ Add-on Item. In Stock. Ships from. Find a Jodeci - Forever My Lady first pressing or reissue. Complete your Jodeci collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Find album reviews, stream songs, credits and award information for Forever My Lady - Jodeci on AllMusic - - A pair of brother acts combined forces to. Forever my Lady is the first solo album to be made by the group that many consider to be the best soul band of the nineties. Enoch; 12 videos; , views; Last updated on Apr 23, Subscribe! Play חנוך .(Although some of the. Jodeci - Forever My Lady (Full album + Bonus all. Share. Loading Save. Listen to songs from the album Forever My Lady, including "Stay", "Come & Talk to Me", "Forever My Lady", and many more. Buy the album for. Forever My Lady is the debut studio album by American R&B quartet Jodeci, released May 28, , by Uptown Records and MCA Records. The album's. Stream Forever My Lady (Album Version) by Jodeci from desktop or your mobile device. Forever My Lady. By Jodeci. • 13 songs. Play on Spotify. 1. Stay. 2. Come & Talk To Me. 3. Forever My Lady. 4. I'm Still. Critically acclaimed as a success by music industry insiders and culture writers of the time period, Forever My Lady was released on May Jodeci's classic album laid the foundation for today's R&B male vocalists. -

Touring Biz Awaits Rap Boom

Y2,500 (JAPAN) $6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), II1I11 111111111111 IIIIILlll I !Lull #BXNCCVR 3 -DIGIT 908 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 863 A06 B0116 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 HOME ENTERTAINMENT THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND Labels Hitching Stars To Clive Greeted As New RCA Chief Global Consumer Brands Artists, Managers Heap Praise On Davis, But Some Just Want Stability given five -year contracts, according BY MELINDA NEWMAN BY BRIAN GARRITY Goldstuck had been pres- While managers of acts signed to to Davis. NEW YORK -In the latest sign of J Records. Richard RCA Records are quick to praise out- ident/C00 that the marketing of music is will continue as executive going RCA Music Group (RMG) Sanders undergoing a sea change, the RCA Records. chairman Bob Jamieson, they are also VP /GM of major labels are forging closer ties "We absolutely loved and have heralding the news that J Records with global consumer brands in with Bob Jamieson head Clive Davis will now control enjoyed working an effort to gain exposure for their and hope our paths will cross with him both the J label and RCA Records. acts. As the deals become more says artist manager Irving BMG announced Nov. 19 that it is again," pervasive, they raise questions for whose client Christina Aguilera buying out Davis' 50 %, stake in J Azoff, artists, who have typically cut on RCA Oct. 29. "I've Records -the label he formed in released Stripped their own sponsorship deals. -

Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change

The I and the We: Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change April K Henderson That the Samoan sense of self is relational, based on socio-spatial rela- tionships within larger collectives, is something of a truism—a statement of such obvious apparent truth that it is taken as a given. Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Taisi Efi, a former prime minister and current head of state of independent Sāmoa as well as an influential intellectual and essayist, has explained this Samoan relational identity: “I am not an individual; I am an integral part of the cosmos. I share divinity with my ancestors, the land, the seas and the skies. I am not an individual, because I share a ‘tofi’ (an inheritance) with my family, my village and my nation. I belong to my family and my family belongs to me. I belong to my village and my village belongs to me. I belong to my nation and my nation belongs to me. This is the essence of my sense of belonging” (Tui Atua 2003, 51). Elaborations of this relational self are consistent across the different political and geographical entities that Samoans currently inhabit. Par- ticipants in an Aotearoa/New Zealand–based project gathering Samoan perspectives on mental health similarly described “the Samoan self . as having meaning only in relationship with other people, not as an individ- ual. This self could not be separated from the ‘va’ or relational space that occurs between an individual and parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and other extended family and community members” (Tamasese and others 2005, 303). -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

28 February 1993 CHART #848 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums I Will Always Love You Sweet Thing The Bodyguard OST Duophonic 1 Whitney Houston 21 Mick Jagger 1 Various 21 Charles & Eddie Last week 1 / 9 weeks Platinum / BMG Last week 50 / 2 weeks WARNER Last week 1 / 8 weeks Platinum / BMG Last week - / 1 weeks EMI Love Is In The Air Stairway To Heaven Breathless Use Your Illusion I 2 John Paul Young 22 Rolf Harris 2 Kenny G 22 Guns N' Roses Last week 4 / 8 weeks SONY Last week - / 1 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 3 / 6 weeks Gold / BMG Last week 14 / 52 weeks Platinum / BMG New York City Steam Unplugged 3 Years, 5 Months & 2 Days In The Li... 3 Charles & Eddie 23 Peter Gabriel 3 Eric Clapton 23 Arrested Development Last week 2 / 4 weeks EMI Last week 24 / 6 weeks VIRGIN Last week 2 / 23 weeks Platinum / WARNER Last week 32 / 5 weeks EMI You Don't Treat Me No Good You Ain't Thinking (About Me) Live-The Way We Walk-Volume One... Best Of Huey Lewis & The News 4 Sonia Dada 24 Sonia Dada 4 Genesis 24 Huey Lewis & The News Last week 6 / 11 weeks Gold / FESTIVAL Last week 22 / 3 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 7 / 9 weeks Platinum / VIRGIN Last week 37 / 12 weeks Platinum / EMI Please Don't Go Ray Of Shine Cooleyhighharmony What Hits? 5 Boyz II Men 25 JPS Experience 5 Boyz II Men 25 Red Hot Chili Peppers Last week 3 / 5 weeks POLYGRAM Last week - / 1 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 4 / 16 weeks Platinum / POLYGRAM Last week 25 / 15 weeks Platinum / EMI End Of The Road Be Someone / Underground Wandering Spirit Ten 6 Boyz II Men 26 Dead Flowers 6 Mick Jagger 26 Pearl -

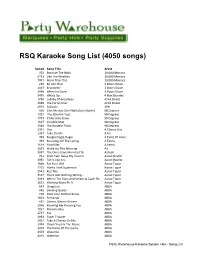

Karaoke 4050 Song List

RSQ Karaoke Song List (4050 songs) Song# Song Title Artist 302 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 2133 Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs 1901 More Than This 10,000 Maniacs 285 Be Like That 3 Doors Down 2047 Kryptonite 3 Doors Down 3446 When Im Gone 3 Doors Down 3435 Whats Up 4 Non Blondes 1798 Lullaby Of Broadway 42nd Street 3089 The Partys Over 42nd Street 2879 Sukiyaki 4PM 866 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 1201 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 1373 If She Only Knew 98 Degrees 1687 Invisible Man 98 Degrees 3046 The Hardest Thing 98 Degrees 2331 One A Chorus Line 2937 Take On Me A Ha 393 Boogie Oogie Oogie A Taste Of Hone 409 Bouncing Off The Ceiling A Teens 1619 Floorfiller A Teens 3563 Woke Up This Morning A3 3087 The One I Gave My Heart To Aaliyah 762 Dont Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville 2951 Tell It Like It Is Aaron Neville 1646 For You I Will Aaron Tippin 1103 Honky Tonk Superman Aaron Tippin 2042 Kiss This Aaron Tippin 3147 There Aint Nothing Wrong... Aaron Tippin 3483 Where The Stars And Stripes & Eagle Fly Aaron Tippin 3572 Working Mans Ph.D. Aaron Tippin 543 Chiquitita ABBA 652 Dancing Queen ABBA 720 Does Your Mother Know ABBA 1603 Fernando ABBA 851 Gimme Gimme Gimme ABBA 2046 Knowing Me Knowing You ABBA 1821 Mamma Mia ABBA 2787 Sos ABBA 2893 Super Trouper ABBA 2921 Take A Chance On Me ABBA 2974 Thank You For The Music ABBA 3078 The Name Of The Game ABBA 3370 Waterloo ABBA 4018 Waterloo ABBA Party Warehouse Karaoke System Hire - Song List Song# Song Title Artist 1660 Four Leaf Clover Abra Moore 2840 Stiff Upper Lip -

Tuesday, June 23, 2020 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20 Sensational Start to Angus Bull Week Page 3

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 SENSATIONAL START TO ANGUS BULL WEEK PAGE 3 PAGES 6-8, 10-11, COVID-19 13, 16, 21 • Govt considering charging for hotel quarantines • Sceptical Rotorua residents asked to trust quarantine process • District health boards set to up Covid-19 testing • Back to business in New York HEALTHTOWN SYSTEM MOURNS OVERHAUL ACCEPTEDVICTIMS BY GOVERNMENT OF TERRORIST ATTACK FOR TODAY, SHE’LL REMEMBER THEIR SMILES: New Zealand singer and songwriter Annie Crummer gives Campion College student Levi Alexander a helping hand as he works on a piece of music he created as part of a two-day workshop. While it was a great learning opportunity for aspiring young musos, Crummer said it was also an inspiring and enjoyable experience for her as well. Campion College head of music Jarrod Seaton said she brought a deep love for music to the workshop and insight into how to bring out the best in young people. STORY ON PAGE 2 Picture by Liam Clayton PAGE 14 Refining the future Moving away from oil dependency through biorefinery project by Matai O’Connor everyday products, with real markets, so shift to more sustainable materials, underutilised, Mr Kohn said, with a lot of that oil can stay in the ground,” he said. greener supply chains and production of the wood going to China. TAIRAWHITI could be the first region Being from different regions across less intense chemicals,” said Dr Dedual, “We foresee that a lot of the wood will in New Zealand with its own biorefinery, New Zealand, the company founders the company’s chief technological officer. -

All Audio Songs by Artist

ALL AUDIO SONGS BY ARTIST ARTIST TRACK NAME 1814 INSOMNIA 1814 MORNING STAR 1814 MY DEAR FRIEND 1814 LET JAH FIRE BURN 1814 4 UNUNINI 1814 JAH RYDEM 1814 GET UP 1814 LET MY PEOPLE GO 1814 JAH RASTAFARI 1814 WHAKAHONOHONO 1814 SHACKLED 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 20 FINGERS SHORT SHORT MAN 28 DAYS RIP IT UP 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 JAYS IN MY EYES 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO 3 THE HARDWAY ITS ON 360 FT GOSSLING BOYS LIKE YOU 360 FT JOSH PYKE THROW IT AWAY 3OH!3 STARSTRUKK ALBUM VERSION 3OH!3 DOUBLE VISION 3OH!3 DONT TRUST ME 3OH!3 AND KESHA MY FIRST KISS 4 NON BLONDES OLD MR HEFFER 4 NON BLONDES TRAIN 4 NON BLONDES PLEASANTLY BLUE 4 NON BLONDES NO PLACE LIKE HOME 4 NON BLONDES DRIFTING 4 NON BLONDES CALLING ALL THE PEOPLE 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 4 NON BLONDES SUPERFLY 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN 4 NON BLONDES MORPHINE AND CHOCOLATE 4 NON BLONDES DEAR MR PRESIDENT 48 MAY NERVOUS WRECK 48 MAY LEATHER AND TATTOOS 48 MAY INTO THE SUN 48 MAY BIGSHOCK 48 MAY HOME BY 2 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER GOOD GIRLS 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER EVERYTHING I DIDNT SAY 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER DONT STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER KISS ME KISS ME 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT WINDOW SHOPPER 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT AND JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AYO TECHNOLOGY 6400 CREW HUSTLERS REVENGE 98 DEGREES GIVE ME JUST ONE NIGHT A GREAT BIG WORLD FT CHRISTINA AGUILERA SAY SOMETHING A HA THE ALWAYS SHINES ON TV A HA THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS A LIGHTER SHADE OF BROWN ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON -

ANNUAL Report for the Year Ended 30 June 2013

ANNUAL REPORT For the year ended 30 june 2013 NZ On Air / Irirangi Te Motu Annual REPORt 2013 / TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 / Highlights 2 Chair's Introduction 4 Who We Are 5 Achieving Our Outcomes 6 Audiences / Focus On Online 8 Audiences / Focus On Prime-Time 10 Audiences / Focus On Documentaries 13 Audiences / Focus On New Zealand Music 14 Audiences / Focus On Ma- ori 18 Audiences / Focus On Pasifika 19 Audiences / Focus On Special Interest 20 Environment 21 Research 22 Operations 24 Part 2 / AccoUntabILITY StateMents Independent Auditor’s Report 30 Statement Of Comprehensive Income 31 Statement Of Financial Position 32 Statement Of Changes In Equity 33 Statement Of Cash Flows 34 Notes To The Financial Statements 35 Statement Of Service Performance 51 APPENDICES 56 DIRECTORY 72 NZ On Air / Annual Report 2013 1 HIGHLIGHTS N g a- Taumata Diversity Nga- Rerenga We focused the Digital Media Fund on Our MakingTracks funding scheme We delivered something for everyone content for special interest audiences backed 247 recordings and videos, on television – with more than 93 hours because these audiences are less well both mainstream and alternative. of drama and comedy, 169 hours of served by mainstream media. This documentary and current affairs, and 600 The funded songs span a wide range year we offered special opportunities to hours of childrens’ and special interest of genres including pop, rock, folk, create Pacific content. programmes. country, te reo, roots and reggae, The successful web-series musical The heavy metal, urban and hip hop. We maintained a balance of mainstream Factory created a strong community and special interest programming. -

Annual Report 2008-2009 PDF 5.9 MB

NZ On Air Annual Report For the year ended 30 June 2009 Proudly supporting local content for 20 years 1989-2009 Annual Report For the year ended 30 June 2009 Table of contents Table of contents Part 1 Our year 1 Highlights 1 Who we are 2 Mission statement and values 2 Chair’s introduction 3 Key achievements 4 Television funding 4 Maori broadcasting 10 Radio funding 11 Digital funding 13 NZ Music funding 14 Archiving funding 16 Research 17 Consultation 18 Operations 18 Main performance measures 20 Part 2 Accountability statements 21 Statement of responsibility 21 Audit report 22 Statement of financial performance 23 Statement of financial position 24 Statement of changes in equity 25 Statement of cash flows 26 Notes to the financial statements 27 Statement of service performance 42 Appendices 1. Television funding 51 2. Radio funding 55 3. NZ Music funding 56 4. Music promotion 58 5. Digital and Archiving funding 58 6. Maori broadcasting 59 Directory 60 Download the companion PDF document to see: 20 years of NZ On Air NZ On Air Annual Report to 30 June 2009 1 Part 1: Our Year Highlights • The website NZ On Screen was launched, showcasing historic New Our investments helped create some Zealand television and film online and outstanding success stories this year: winning a Qantas Media Award in its first year • The Top 10 funded television • Our Ethnic Diversity Forum brought programmes had some of our highest all relevant broadcasters together viewing numbers ever around a subject of increasing importance • New Zealand drama successfully