Inyo National Forest Plan Objection Mono County Board of Supervisors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 4, 2019 Regular Meeting Item # 1

June 4, 2019 Regular Meeting Item # 1 Opportunity for Public to Address the Board California Water Boards State Water Resources Control Board Orders 98-05 and 98-07 . STATE OF CALIFORNIA STATE WATER RESOURCES CONTROL BOARD ORDER WR 98 - 0s In the Matter of Stream and Waterfowl Habitat Restoration Plans and Grant Lake Operations and Management Plan Submitted by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Pursuant to the Requirements of Water Right Decision 163 1 (Water Right Licenses 10191 and 10192, Applications 8042 and 8043) SOURCES: Lee Vining Creek, Walker Creek, Parker Creek and Rush Creek COUNTY: Mono LICENSEE: City of Los Angeles ORDER REQUIRING STREAM AND WATERFOWL HABITAT RESTORATION MEASURES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 BACKGROUND . 1 2.0 FINDINGS AND REQUIREMENTS OF DECISION 1631 REGARDING RESTORATION PLANS ...................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Prior SWRCB Findings Regarding Stream Restoration Plans ................................ 3 2.2 Prior SWRCB Findings Regarding Waterfowl Habitat Restoration Plans.. ......... .4 2.3 Prior Findings Regarding Grant Lake Operations and Management Plan ............ 5 2.4 Requirements and Evaluation Criteria Governing Restoration Plans Required by Decision 1631 ........................................................................................... 6 3.0 PREPARATION OF RESTORATION PLANS SUBMITTED BY CITY OF LOS ANGELES . 6 4.0 PARTICIPANTS IN HEARING . 9 5.0 STREAM RESTORATION PLAN AND GRANT LAKE OPERATIONS PLAN ........................................................................................................ -

Winter & Spring 2020 Mono Lake Newsletter

MONO LAKE N E W S L E T T E R W i n t e r & S p r i n g 2 0 2 0 Prescribed Burn to Benefi t Gulls Restoration of Mill Creek Tioga Inn Decision Nears Field Seminars he Mono Basin can feel completely quiet and isolated in winter. Mountain passes close for the season and visitors dwindle to a trickle. Birds have Tfl own to warmer places and it’s as if the whole basin is far away from everything else in the world. But during the prescribed burn on Twain Islet this month I was reminded of how many people see Mono Lake, even in the depths of winter. Mono Lake Offi ce Eastern Sierra neighbors hiking north of the lake took photos of the plumes of Information Center & Bookstore smoke rising near Negit Island. Locals came into the bookstore to inquire about Highway 395 at Third Street the activity out on the lake. Someone called to ask if the volcanoes were erupting! Post Offi ce Box 29 Lee Vining, California 93541 Members keeping an eye on the Mono Lake webcams called in, curious about the (760) 647-6595 boat zipping back and forth. I talked to people watching from Big Pine, San Luis Obispo, Riverside, Reno, and the Midwest. [email protected] • monolake.org Everyone was thrilled to hear about the prescribed burn, an exciting fi rst step in Los Angeles Offi ce a long-planned and carefully coordinated eff ort with the Inyo National Forest and 1718 Wellesley Avenue Los Angeles, California 90025-3634 Point Blue Conservation Science to restore California Gull nesting habitat on the islets that has been taken over by invasive weeds. -

T He L Ost C Reekof M

T H E L O S T C R E E K O F M O N O A Homegrown Struggle for Eastern Sierra Water A S E N I O R T H E S I S B Y S A R A H C A R V I L L • T H E U N I V E R S I T Y O F C A L I F O R N I A , S A N T A C R U Z T H E L O S T C R E E K O F M O N O A Homegrown Struggle for Eastern Sierra Water SUBMITTED TO THE ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE. SARAH CARVILL MARCH 16, 2007 The University of California, Santa Cruz C O N T E N T S ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v REGIONAL MAP vii A FEW OF THE CHARACTERS ix PROLOGUE: JUNE AND AUGUST 1 PART I: THE WATERSCAPE 5 A Stream in Three Parts 7 Rights from Another Time 9 The Waterfowl Plan: Getting the Ducks in a Row 11 Los Angeles in Context: The Devil Makes Three 13 Two Histories, One Stream 15 PART II: THE TROUBLE 19 Fiasco on the Field Trip 21 People for Mono Basin Preservation: A Sagebrush-roots Rebellion 23 Winter 1996-1997: “Screaming Matches Over Restoration” 25 Information Problems: Believe What You Want 27 CREW: A Local Solution 29 The Board Hearings: Going to the Heart 30 The Price of Participation 33 The Restoration Orders: One Door Closes 35 PART III: THE AFTERMATH 37 Conway and DeChambeau: Tying Down the Water 39 The Lundy Project: A Last Ditch Effort 41 1999: A License Only its Mother Could Love 42 Things Fall Apart: “Spinning” and Signing on the Line 44 CONCLUSION: THE BALANCE SHEET 47 NOTES 53 APPENDIX: FIGURES & TABLE A C K N O W L E D G M E N T S From the end of May, 2006, to the middle of March, 2007, “my thesis” and “my life” were more or less interchangeable terms. -

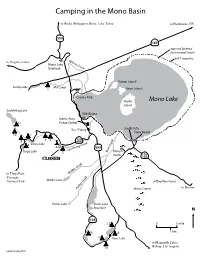

Camping in the Mono Basin

Camping in the Mono Basin to Bodie, Bridgeport, Reno, Lake Tahoe to Hawthorne, NV 395 167 exposed lakebed (recessional lands) ' ' ' ' 6417 shoreline to Virginia Lakes Wilson Creek Mono Lake Overlook “Gaines Island” Lundy Lake Mill Creek 1 Negit Island County Park Paoha Mono Lake Island Saddlebag Lake Old Marina Scenic Area 11 Visitor Center Lee Vining South Tufa • Navy Beach 10 7 6 120 9 5 west 8 Ellery Lake 4 395 3 Lee Vining Creek Tioga Lake 2 Rush CreekPanum Crater 120 closed east to Tioga Pass, Walker Creek Yosemite National Park Walker Lake Jeffrey Pine Forest to Benton Parker Creek Mono Craters Parker Lake Grant Lake Reservoir N 158 12 0 1 mile 16 13 1 km 15 •June Lake to Mammoth Lakes, 14 Bishop, Los Angeles updated July 2010 CAMPGROUND CAMPING # Campground Sites Water Fee ($) Elevation 1 Lundy Canyon 60 no 8 7,600 2 Lower Lee Vining 54 no 14 7,300 3 Cattleguard closed 16 no 14 7,300 4 Moraine 27 no 14 7,350 5 Aspen 56 yes 14 7,500 6 Big Bend 17 yes 19 7,800 7 Ellery Lake 21 yes 19 9,500 8 Tioga Lake 13 yes 19 9,700 9 Junction 13 no 14 9,600 10 Sawmill Walk-In 12 no 14 9,800 11 Saddlebag Lake 20 yes 19 10,000 12 Oh Ridge 144* yes 20 7,600 13 June Lake 28* yes 20 7,600 14 Reversed Creek 17 yes 20 7,600 15 Gull Lake 11 yes 20 7,600 16 Silver Lake 63* yes 20 7,200 17 Aerie Crag 10 (RV only) no 11 7,200 * indicates campgrounds with reservable sites to make reservations, please call 1-877-444-6777 DISPERSED CAMPING AND PERMITS Dispersed camping is allowed on public land in the Mono Basin—the Jeffrey pine forest off of Highway 120 east is a recommended dispersed camping area. -

Mono County Community Development Department P.O

Mono County Community Development Department P.O. Box 347 Planning Division P.O. Box 8 Mammoth Lakes, CA 93546 Bridgeport, CA 93517 (760) 924-1800, fax 924-1801 (760) 932-5420, fax 932-5431 [email protected] www.monocounty.ca.gov March 2007 MONO BASIN WATERSHED ASSESSMENT 1. Introduction Watershed approach California watershed programs and Mono County’s involvement What is a watershed assessment? Publicly perceived problems and issues Water quantity Water quality Aquatic habitat Recreation Wildfire Invasive species List of assorted issues Publicly perceived key resources Driving questions Watershed boundaries 2. Descriptive geography Climate Precipitation Snowpack Air temperature Wind Evaporation Climate change impacts Topography Geology and soils Upland vegetation Special-status plants Wildfire history and risk 3. Riparian areas and wetlands Rush Creek Parker Creek Walker Creek Bohler Creek Horse Creek Lee Vining Creek Post Office Creek Mill Creek Planning / Building / Code Compliance / Environmental / Collaborative Planning Team (CPT) Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO) / Local Transportation Commission (LTC) / Regional Planning Advisory Committees (RPACs Wilson Creek DeChambeau Creek 4. Fish and wildlife Fish Invasive species Wildlife 5. Human history and land use Land use Agriculture Timber harvesting Mining Gravel extraction Roads Hydroelectric development Residential development Recreation Land ownership and interagency cooperation 6. Descriptive hydrology Runoff generation processes Water balance Streamflow averages and extremes Floods and droughts Lakes Groundwater Diversions and storage Water rights, use and management Domestic water systems Lee Vining Public Utility District Lundy Mutual Water Company June Lake Public Utility District Conway Ranch Wastewater treatment and disposal 7. Descriptive geomorphology Stream channels Surface erosion Hillslope processes Sediment transport Human influences Restoration 8. -

Historic Overview of the Rush Creek and Lee Vining Hydroelectric Projects

.a,. ".".!!_,.~_......:_:"..,; ~ q~< (!!." '\:10'., . .f ..... .)-/t, LJ...] 0_. I ° • l.-t- ! . \" • \' '" 0 I o i tVcNoiAKE RESEARCHI.JBf?AAY o 0 P.O"BOX 29 0 • UE~.V.NING. CA 93,041 IDSTORIC OVERVIEW OF THE RUSH CREEK AND LEE VINlNG CREEK HYDROELECTRIC PROJECTS Project Managers 'Dorothea 1 Theodoratus Clinton M. Blount by Valerie H. Diamond Robert A. Hicks ..\ ..;' "0t- , f v.' fJ Submitted to Southern California' Edison Company Rosemead, California Theodoratus Cultural Research, Inc. Fair Oaks, California August 1988 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research o~ "the Rush Creek and Lee Vining hydroelectric systems was aided by many generous people. We are i~debte.d to.Dr. David White of the Environmental Affairs Division of" Southern California Edison Company (SCE) for his guidance throughout the planning and execution of the. work. Others at SCE's R~semead headquarters who were most helpful were William Myers, Bob Brown, and Gene " Griffith. Our work in the project areas was made Possible by SCE employees Tony Capitato, Don Clarkson, Dennis Osborn, and Stan Lloyd. We are also indebted to Mrs. Jenny Edwards for her kind assistance, .nd to Melodi Anderson for her f~ci1itation of imPortant work at the California State Archives. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Chapter fa= . INTRODUCTION 1 _ Location and Geography .1 Research Goals .. ~'- 1 Personnel ·.4 1 PURPOSES AND METHODS S 2 MOTIVES, PLANS, AND DEVELOPMENT: 1890s-1917 '7 James Stuart Cain 7 Delos Allen Chappell 9 Pacific Power Company 9 ~ RUSH CREEK. DEVELOPMENT: THREE STAGES, 1915-1917 13 Stage One: Transportation and Initial Construction 13 Stage Two: Dams and Powerhouse 19 Stage Three: Second Flowline and Generating Unit 20 4 A NEW MARKET, IMPROVEMENT AND CONSTRUCTION: 1917-1924 22 Rush Creek and Nevada-California and Southern Sierras Power Companies 22 Lee Vining Creek Developments . -

Mono Basin Camping

Camping in the Mono Basin to Bodie, Bridgeport, Reno, Lake Tahoe to Hawthorne, NV 395 167 exposed lakebed (recessional lands) ' ' ' ' 6417 shoreline to Virginia Lakes Mono Lake Overlook “Gaines Island” Lundy Lake Mill Creek 1 Negit Island County Park Paoha Mono Lake Island Saddlebag Lake Old Marina Saddlebag Lake Road Scenic Area 9 Poole Power Visitor Center Plant Road Lee Vining South Tufa • Navy Beach 8 5 4 120 7 3 west 6 Ellery Lake 395 Lee Vining Creek Tioga Lake 2 Rush CreekPanum Crater 120 east to Tioga Pass, Walker Creek Yosemite National Park Walker Lake Jeffrey pine forest to Benton Parker Creek Mono Craters Parker Lake Grant Lake Reservoir N 158 15 10 0 1 mile 14 11 1 km 13 •June Lake to Mammoth Lakes, 12 Bishop, Los Angeles updated August 2016 CAMPGROUND CAMPING # Campground Sites Water Fee Elevation 1 Lundy Canyon 60 no $16 7,600 2 Lower Lee Vining 60 no $14 7,300 3 Aspen 56 yes $14 7,500 4 Big Bend 17 yes $19 7,800 5 Ellery Lake 12 yes $19 9,500 6 Tioga Lake 13 yes $19 9,700 7 Junction 13 no $14 9,600 8 Sawmill Walk-In 12 no $14 9,800 9 Saddlebag Lake 20 yes $19 10,000 10 Oh Ridge 143* yes $23 7,600 11 June Lake 28* yes $20 7,600 12 Reversed Creek 17 yes $20 7,600 13 Gull Lake 11 yes $20 7,600 14 Silver Lake 63* yes $20 7,200 15 Aerie Crag 10 (RV only) no $12 7,200 * indicates campgrounds with reservable sites to make reservations, please call 1-877-444-6777 DISPERSED CAMPING AND PERMITS Dispersed camping is allowed on public land in the Mono Basin—the Jeffrey pine forest off of Highway 120 east is a recommended dispersed camping area. -

News, Views & Culture of the Eastern Sierra

sheetthe News, Views & Culture of the Eastern Sierra Larissa French was all smiles at the Husky Club’s “Fun with Police and Wheels BBQ” this past Tuesday. Saturday, June 22, 2019 FREE Vol. 17, No. 25 TIOGA PASS ROAD WILL ALLOW OPEN THE DOOR, LIMITED ACCESS STARTING JUNE 21 AND LET TIOGA INN Press Release Will Mono County ring bell for new hotel development? osemite National Park Flat Junction and at Tioga for all backpackers to be aware By Gorman announced Thursday Pass. of the timing that the road is he Mono County Planning Robertson then asked a series Ythere will be limited Visitors are encouraged to open and closed and to plan Commission met Thurs- of questions about the hous- access to Tioga Road (Highway plan their trips over Tioga their trip logistics accordingly. Tday to discuss a massive ing. She was concerned that 120 East) for visitors interested Road in advance and to Any backpacker who misses- new development proposed at there was no stipulation for rent in crossing the Sierra. prepare for the restricted ac- the road open period will need the junction of Highways 395 control on the units. Through- Tioga Road will be open to cess and no access to visitor to be prepared to spend an and 120. out the plan the 150 new units all vehicles, including bicycles, services. The road will remain additional night in the wilder- The Tioga Inn would include are referred to as “workforce from 10-11 a.m. and from 3-4 closed outside of these times ness. -

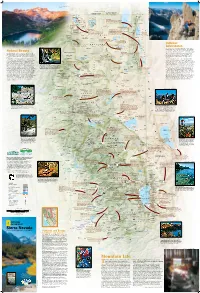

Sierra Nevada’S Endless Landforms Are Playgrounds for to Admire the Clear Fragile Shards

SIERRA BUTTES AND LOWER SARDINE LAKE RICH REID Longitude West 121° of Greenwich FREMONT-WINEMA OREGON NATIONAL FOREST S JOSH MILLER PHOTOGRAPHY E E Renner Lake 42° Hatfield 42° Kalina 139 Mt. Bidwell N K WWII VALOR Los 8290 ft IN THE PACIFIC ETulelake K t 2527 m Carr Butte 5482 ft . N.M. N. r B E E 1671 m F i Dalton C d Tuber k Goose Obsidian Mines w . w Cow Head o I CLIMBING THE NORTHEAST RIDGE OF BEAR CREEK SPIRE E Will Visit any of four obsidian mines—Pink Lady, Lassen e Tule Homestead E l Lake Stronghold l Creek Rainbow, Obsidian Needles, and Middle Fork Lake Lake TULE LAKE C ENewell Clear Lake Davis Creek—and take in the startling colors and r shapes of this dense, glass-like lava rock. With the . NATIONAL WILDLIFE ECopic Reservoir L proper permit you can even excavate some yourself. a A EM CLEAR LAKE s EFort Bidwell REFUGE E IG s Liskey R NATIONAL WILDLIFE e A n N Y T REFUGE C A E T r W MODOC R K . Y A B Kandra I Blue Mt. 5750 ft L B T Y S 1753 m Emigrant Trails Scenic Byway R NATIONAL o S T C l LAVA E Lava ows, canyons, farmland, and N E e Y Cornell U N s A vestiges of routes trod by early O FOREST BEDS I W C C C Y S B settlers and gold miners. 5582 ft r B K WILDERNESS Y . C C W 1701 m Surprise Valley Hot Springs I Double Head Mt. -

Watershed Analysis for Mill, Deer and Antelope Creeks

KRIS edition Watershed Analysis for Mill, Deer, and Antelope Creeks Watershed Analysis For Mill, Deer, and Antelope Creeks Almanor Ranger District Lassen National Forest Prepared By The Watershed Analysis Team: Scott Armentrout Howard Brown Susan Chappell Mignon Everett-Brown JoAnn Fites Judy Forbes Melanie McFarland Jules Riley Ken Roby Anita Villalovos Roger Walden Diane Watts Michael R. Williams Watershed Analysis for Mill, Deer, and Antelope Creeks TABLE OF CONTENTS WATERSHED ANALYSIS SUMMARY................................... 1 I. Introduction .................................................................................................................1 II. Environmental Setting................................................................................................ 3 III. Historical Setting ...................................................................................................... 5 IV. Issues and Questions................................................................................................. 9 IV.1. Anadromous Fish (Populations and Habitats) ................................................ 11 IV.2. Native Fish Assemblages................................................................................. 14 IV.3. Late Seral Vegetation, Old Growth, Spotted Owls and other Old Growth Dependent Species.................................................................................................... 15 IV.4. Economic and Social Outputs........................................................................ -

1995 Restoration of Mill Creek Report by Scott Stine

I 1 Restoration of Degraded Riparian, Wetland, and Deltaic , Environments on Mill Creek, Mono County, California , t Report to t Dr. Fritz Reid, Ducks Unlimited I Dr. Rod Drewien, Hornocker Wildlife Research Mr. Tom Ratcliff, United States Forest Service and the I Los Angeles Department of Water and Power l I I I I I Scott Stine, Ph.D. I Berkeley, California 94702 , November, 1995 I -I I I Restoration of pegraded Riparian. Wetland. and peltaic Enylronments on Mill Creek. Mono County. California Table of Contents I Introduction ...................................................................... ................................... 1 Environmental Setting . ••..• .............. ........... ....... ..... ........... ......................... ....... 1 The bedrock reach (Lundy Canyon) ................... ..... ..... ..... ......... ................... 2 I The Pleistocene Delta Reach ............. .............. ......... ........... ............... ........ 2 The Holocene Delta Reach-Mill Creek's Interior and exterior delta ........ ......... 3 History of Diversions .............................................................. .......... ............ .... 3 Degradation of the Mill Creek Bottomlands ........................ .......................... 5 I Restoring the Mill Creek Bottomlands ................. ~......................................... 6 Introduction .................................. ..................... ...... ......... ............... ........... 6 The abandoned channels: Delineation ........................................................ -

North Mono Basin Watershed Analysis

North Mono Basin Watershed/Landscape Analysis Appendices Index of Appendices: Appendix A. List of Hydrology/Water Use Information Sources for the Mill/Wilson Area………………………………….. 2 Appendix B. Hydrologic Condition Assessment (Kattelman)…….. 7 Appendix C. Spreadsheet Documentation (Vorster) ………………32 Appendix D. Draft North Mono Basin Road Analysis (2001) …….40 Appendix E. Riparian Vegetation (Nelson)………………………...64 Appendix F. Wildlife Species – Conway Ranch …………………...74 Appendix G. Thompson Ranch Bird Census ………………………76 1 Appendix A LIST OF HYDROLOGY/WATER USE INFORMATION SOURCES FOR THE MILL/WILSON AREA Hydrologic measurements (ongoing - continuous and spot measurements) Publisher/Collector Drainage Date of msmt. or pub. LADWP (LADWP has SSP Mill, Wilson, and irrigation 1911? - present measurements) diversions Lundy Mutual Water Water wells ?-present Company .SCE and predecessors Mill, Wilson, and irrigation 1911? - present diversions Hydrologic measurements (special studies - mainly spot) Publisher/Collector Drainage Date of msmt. or pub.. Beak Consultants Wilson Creek for Conway 1986-89 Ranch EIR BLM (Patti Gradek) Water resources survey on 1980-81? BLM lands BLM (Terry Russi) Wilson Creek, map showing 1996-97 gains and losses CADFG and Foster- Mill Creek, for instream 1990-91 Wheeler Environmental flow study; CADFG and Foster- Wilson Creek for instream 1990-91 Wheeler Environmental flow study MLC Mill, Wilson, and irrigation 1996-97 diversions, visual estimates SCE and EA Engineering Mill Creek for relicensing 1985-1993? studies USFS Mill Creek and Wilson 1997 Creek 2 USFS Mill Creek for relicensing ? Hydrologic and water management analysis: reports and testimony focused on Mill/Wilson system. Author Title Date Relevant Information Physical Location Applied Groundwater 1987 Groundwater resource Mono Geotechnolo resource and lake and lake construction County gy construction irrigation for Conway Planning irrigation for Ranch Dept.