ART HISTORY PAPER MILTON AVERY Submitted by Scott Ervin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Milton Avery and the End of Modernism

CHAPTER I FORMATIVE YEARS Milton Avery, the son of Russell Eugene and Esther March Avery, was born in Altmar, New York, a small town near Oswego, on March 7, 1885. When Avery was eight years old, his family moved to Hartford, Connecticut, his home for the next twenty-four years. Upon graduating from high school he took a low-paying job at a local typewriter factory, but in hopes of finding more lucrative employment as a commercial artist he applied for a course in lettering at the Connecticut League of Art Students in Hartford. Unable to gain admittance to the over-crowded lettering class, he opted for a drawing course at the League taught by Charles Noel Flagg and Albertus Jones. This single semester of drawing in charcoal was Avery’s only formal art training in a painting career that would span more than fifty years. Avery began painting directly from nature in the rural area around Hartford known as the East Meadows, and also began his lifelong practice of sketching the human figure. He began working a night shift at the United States Tire and Rubber Company in order to free his daylight hours for painting. Avery spent the next twelve years of his life working and painting in almost complete obscurity. He would always modestly refer to the activity of painting as a “favorite pastime.” 1 In the summer of 1925, Avery, now 40, traveled to the artists’ colony in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where he met Sally Michel, a young artist and illustrator from Brooklyn. That fall he moved to New York to be with Sally, and in the spring of 1926 they were married. -

Milton Avery Milton Avery Selected Works from the Estate of the Artist

MILTON AVERY MILTON AVERY SELECTED WORKS FROM THE ESTATE OF THE ARTIST OCTOBER 6 - NOVEMBER 3, 2012 STILL LIFE WITH TWISTED BREAD 1937, Oil on board 24 x 20 inches (61 x 50.8 cm) Avery’s genius lay in his ability to portray moods that stimulate each viewer’s consciousness on an almost ar - chetypal level. As the depiction of iconic relationships came to dominate his work, his paintings acquired greater poignancy. In relinquishing the transitory and the specific, Avery bestowed on his subjects a suspended calm. Depictions of group activities - family and friends playing games, making music, relaxing together at the beach - were replaced by a quality of separateness. Figure portrayals were now generally of single figures or of couples isolated in otherwise deserted landscapes. This mood of emptiness and quietude extended to his landscapes and seascapes as well; even in these, pictorial incidents seldom intrude upon the limitless expanse of empty space. Avery`s portraits and figure compositions were typical of the work that dominated the New York art scene in the twenties: his close - cropped individual portraits isolated against flat backgrounds related to the academic paintings of artists at the Art Students League, while his figure groups were similar to the urban genre paint - ings of artists later identified with the American Scene. -Barbara Haskell, Milton Avery, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1982 COVER: (detail) POOL PLAYER 1929, Oil on canvas, 36 x 28 inches (91.5 x 71.1 cm) REFLECTED ARTIST 1927, Oil on board 20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.6 cm) PING PONG PLAYERS 1942, oil on board 19 1/4 x 11 1/8 inches (48.8 x 28.2 cm) Signed "Milton" lower left and "Avery" lower right Private Collection POOL PLAYER 1929, Oil on canvas 36 x 28 inches (91.5 x 71.1 cm) YOUNG ARTIST 1935, Oil on board 20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.6 cm) ARTIST 1939, Oil on board 19 x 15 inches (48.3 x 38.1 cm) VIOLINIST n. -

Milton Avery 1893 - 1965

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1966 Milton Avery 1893 - 1965 Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Frank Getlein Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A. and Getlein, Frank, "Milton Avery 1893 - 1965" (1966). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 106. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/106 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Photograph by Dena Milton Avery 1893 - 1965 The Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery University of Nebraska, Lincoln April 3 through May 1, 1966 The Arkansas Arts Center MacArthur Park, Little Rock May 6 through June 26, 1966 Acknowledgments For The Arkansas Arts Center Officers of The Board of Trustees of The Arkansas Arts Center Mrs. Winthrop Rockefeller, President Frank Lyon, Vice President Frank Whitbeck, Secretary Ed Lovett, Treasurer Mrs. Harry Pfeifer, Jr., Chairman, Exhibition Committee Staff of The Arkansas Arts Center Louis F. Ismay, Executive Director Miss Anne Long, Assistant Director Zoltan F. Buki, Director of Exhibitions Daniel K. Teis, Director of Education Dugald MacArthur, Director of Theatre Mrs. Sanford Besser, Director of State Services John Thornton, Curator of Artmobile John Belford, Director of Public Relations Mrs. Margaret Wickard, Secretary Acknowledgments For The Nebraska Art Association Mrs. -

![Summer with the Averys [Milton | Sally | March] Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Connecticut May 11 – September 1, 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1872/summer-with-the-averys-milton-sally-march-bruce-museum-greenwich-connecticut-may-11-september-1-2019-701872.webp)

Summer with the Averys [Milton | Sally | March] Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Connecticut May 11 – September 1, 2019

Press Release Summer with the Averys [Milton | Sally | March] Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Connecticut May 11 – September 1, 2019 Milton Avery (American, 1885-1965). Swimmers and Sunbathers, 1945. Oil on canvas, 28 x 48 1/4 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Roy R. Neuberger, 1951 (51.97). © 2019 The Milton Avery Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY. GREENWICH, CT, March 28, 2019 – On May 11, 2019, the Bruce Museum will open Summer with the Averys [Milton | Sally | March]. Featuring landscapes, seascapes, beach scenes, and figural compositions—as well as rarely seen travel sketchbooks—the exhibition takes an innovative approach to the superb work produced by the Avery family. Along with canonical paintings by Milton Avery, the show offers a unique opportunity to become acquainted with the remarkable art created by Avery’s wife Sally and their daughter March. In the summer of 1924, while painting in the fishing port and artist’s colony of Gloucester, Massachusetts, Avery met young artist Sally Michel, whom he would marry less than two years later. They would return to Gloucester and elsewhere in New England for summertime visits during the following decade, sometimes with close friends Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman. Page 1 of 4 Press Release After March Avery’s birth in 1932, the three Averys ventured forth over the years as far south as Mexico (including six weeks at San Miguel de Allende); west to Laguna Beach, California; and north to Canada’s Gaspé Peninsula. -

Fine Modern Art

FINE MODERN ART Tuesday, November 19, 2019 NEW YORK FINE MODERN ART AUCTION Tuesday, November 19. 2019 at 10am EXHIBITION Friday, November 15, 10am – 5pm Saturday, November 16, 10am – 5pm Sunday, November 17, Noon – 5pm LOCATION DOYLE 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalogue: $35 CONTENTS INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATES OF FINE MODERN ART Arthur Brandt Paintings 1001-1030 Claire Chasanoff Prints 1131-1164 A Gentleman, Park Avenue and Southampton, New York Carl Lesnor Glossary I Dorothy Lewis 2013 Irrevocable Trust Conditions of Sale II Peter Mayer Terms of Guarantee IV Ruth Schapira Information on Sales & Use Tax V Carol Schein Buying at Doyle VI Leonard and Elaine Silverstein, Bethesda, MD Selling at Doyle VIII Frederieke Sanders Taylor Auction Schedule IX Company Directory X INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM Absentee Bid Form XII A New York Corporate Collection A Private New York Collector PAINTINGS Lot 1051 1005 1006 1003 1001 1002 1004 1007 1008 1001 1002 1003 1004 1005 1006 1007 1008 Eric Aho Arman Arman Jeans Hans Arp Milton Avery Edmondo Bacci Donald Baechler William H. Bailey American, b. 1966 French, 1928-2005 French, 1928-2005 German/French, 1886-1966 American, 1885-1965 Italian, 1913-1978 American, b. 19567 American, b. 1930 Black Soil, Blue Barn Zeus Venus Untitled, 1956 Letter Writer B-8 Water Closet Drawing #1, 1985 Seated Nude, 1991 Signed Eric Aho (uc) Signed Arman, inscribed Bronze with brown patina Signed Arp twice and marked with artist’s Signed Milton Avery in ballpoint Signed Bacci (lr), inscribed Gouache on paper Signed Bailey, dated 1991 and Oil on canvas Bocquel Fd. -

Milton Avery. New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc., 1990; Pp

Milton Avery. New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc., 1990; pp. 29-31+225. Text © Robert Hobbs MILTON AVERY ilton Avery is a consummate sophisticate who maintains a witty dialogue with European modernists, with his American peers, and with fine and folk-arr traditions. Although he was generally M quiet in his daily life, preferring to leave the art of conversation to others, in his painting he was loquacious: he maintained as many as two and sometimes three simultaneous conversations with other artists in a single work. Avery's arr is collaborative in the true sense of working with culture, for it responds to various aspects of his world, making delightful, incisive ripostes and becoming by turns modern, na"ive, realistic, and abstract, depending on the arr to which he was responding. One can enjoy Avery's painting without recognizing his artistic dialogues, but an understanding of his responses adds immeasurably to one's appreciation of the quality and charm of his art and the subtle, dry wit that he only occasionally revealed in his everyday conversations with family and friends. 29 Avery created a charming and delightful body of work featuring family and friends, intimate settings, and landscapes encountered on summer holidays. In his work he embraced many of the attitudes of modern French art that the Fauves Raoul Dufy and Henri Matisse espoused, particularly their concern with saturated color in distinctly new combina tions coupled with an interest in retaining the two-dimensional character of the canvas or paper on which they worked. Modern critics have considered Avery's work to be such an extension of Fauvism that he has frequently been referred to as the '1\rnerican Matisse." 1 While he held Matisse's art in high regard along with Dufy's, and respected a number of other School of Paris painters, including Pablo Picasso, he also brought to his art an understanding of American Impressionism and an appreciation of American folk art that allowed him to create a distinctly native brand of modernism. -

Milton Avery

Victoria Miro Milton Avery Private View 6 – 8pm, Tuesday 6 June 2017 Exhibition 7 June – 29 July 2017 Victoria Miro Mayfair, 14 St George Street, London W1S 1FE Image: Wader, 1963 Oil on canvas 60.96 x 76.2 cm, 24 x 30 in © 2017 The Milton Avery Trust/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York Victoria Miro is delighted to announce an exhibition of works by Milton Avery at its Mayfair gallery. A solo presentation will take place at Art Basel (15 – 18 June 2017). One of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, Milton Avery (1885 – 1965) is celebrated for his luminous paintings of landscapes, figures and still lifes, which balance distillation of form with free, vigorous brushwork and lyrical colour. The gallery’s first exhibition by Avery since announcing its European representation of Milton Avery’s work, and also the first exhibition of the artist’s work in London for ten years, features paintings and works on paper from throughout his career, ranging in date from the 1930s to the 1960s. Included are pairings of Avery’s oils and associated works on paper, in addition to works created as a result of his sole trip to Europe in 1952, when he visited London, Paris and the South of France. Many of the works on display have never been exhibited outside of the US. An accompanying publication will include an essay by Edith Devaney, Contemporary Curator at the Royal Academy of Arts and co-curator of the recent Abstract Expressionism exhibition (currently on display at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao), examining the development of Avery’s career and his influence within the canon of American art. -

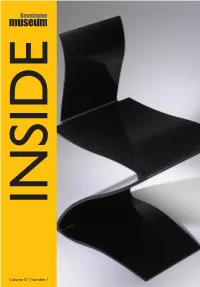

Volume 37 | Number 1

Volume 37|Number 1 INSIDE Director’s Letter: 3D Digital Here and Now Over the last fifteen years, there has been a profound transformation taking place in the way things are made, all across the world, and here in Bennington too. One of the most interesting aspects of this, for us, is actually how Bennington is tied in with the wider world. So it is very exciting for me to introduce Bennington Museum’s spring exhibition – 3D Digital: Here and Now. This show is about “high tech” but it’s not high tech as we usually understand it—the virtual world of apps and programming. This show is emphatically about the physical world. It’s also about the profound impact that digital design and automated fabrication are having on making and manufac- turing, both single objects, made by artists, and objects made thirty or thirty thousand at a time by industry. NASA 3D-Printed Habitat, “Mission to Mars,” 2015, Güvenç Özel (b. 1980), Digital simulation of 3D- printed Housing for Mars, Courtesy of the artist Producing tangible, 3-dimensional objects using CNC routers, 3D printing, laser cutters, and even digital 3D weaving On the surface, this show has a simple goal: to shine a light presents amazing new possibilities for designing and making on the sophisticated 3D digital design and fabrication going on shapes never possible before, for rapid prototyping, for speed in Bennington right now. We also want to illuminate how things and precision in fabrication, for making relatively small made in Bennington are having an impact around the globe. -

Oral History Interview with Sally Avery, 1982 February 19

Oral history interview with Sally Avery, 1982 February 19 Funding for this interview was provided by the Mark Rothko Foundation. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview Interview with Sally Avery Conducted by Tom Wolf At New York, New York 1982 February 19 & March 19 Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Sally Avery on February 19, 1982 and March 19, 1982. The interview took place in New York, New York, and was conducted by Tom Wolf for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview was conducted as part of the Archives of American Art's Mark Rothko and His Times oral history project, with funding provided by the Mark Rothko Foundation. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. TOM WOLF: This is Tom Wolf. I'm interviewing Sally Avery at her apartment at 300 Central Park West, and it is Friday, February 19, 1982. Now, as I mentioned to you, Mrs. Avery, a lot of the purpose of this interview is to gather material on Rothko and on the relationship between your husband and Rothko and you and Rothko. So, to begin with, when did you first meet Mark Rothko? SALLY AVERY: The first time we met Mark Rothko I think was in either 1929 or 1930. -

Syracuse University Art Galleries

Syracuse University Art Galleries Syracuse University Art Galleries Syracuse University Art Galleries The Syracuse University Art Collection, in association with the including l\1ark Rothko, Barnett It was Louis and Emily Lowe Art is proud to Milton Revisited: Kaufman who introduced to and Kaufman had the Louis and Annette Collection. Milton attended school together in Portland, In New York, met was an artist who helped define American art, often for dinner at tlle where there was a new whose impact on art is still seen in It is pal.nang to see and stimulating conversation to be The Kaufmans that Avery pursued a personal aesthetic at a time when there was enjoyed a lifelong friendship the artist. l-\.s Ted Aiken pressure to create an art that had a nationalistic such as lrrnr.rt='rl during his life, Louis and Annette Kaufinan American Scene painting. \lVhile his the person and the artist." Their relationship with might not have neatly fit into this "''-'.l.JlLLL.I.,('U. figure in American art a collection of art that approach and his commitment to np1~cr\n'll we are very pleased to present. truly 'American.' '-'"'"'-'."'. .1.,.",> to Domenic J. Associate Director of the Louis and Annette Kaufman these and other characteristics University Art Collection, who extensive research on in Milton Avery during their nearly 40 year with the artist and this collection developed the annotated checklist to the exhibition. Since his family. I think Avery recognized NIr. and Mrs. Kaufman's interest in many of these paintings are being seen for the Domenic artistic and creative activities, and certainly their commitment to excel- lllC:lU(leS each object's physical information including slgnat:un~s lence. -

Figuratively Speaking School & Teacher Programs GRADE

Art and Writing Initiative The 1,000 Words Experiment Figuratively Speaking School & Teacher Programs GRADE Tell me a Story How did my work at home complement my husband’s civic contributions? How did I contribute to the founding documents of the United States of America? Museum of Art Program Overview Using the aesthetic and expressive qualities of figurative artworks from the museum’s permanent collection, Figuratively Speaking: Tell Me a Story develops third- grade students’ narrative writing skills while promoting state and national curriculum standards in the language and visual arts. Artworks viewed throughout the program serve as students’ texts to be carefully observed, critically analyzed, and thoughtfully interpreted and subsequently act as inspiration for their own narrative compositions. Wadsworth Atheneum Atheneum Wadsworth www.thewadsworth.org/teachers (860) 838-4170 1 Program Structure and Logistics This program consists of four independent components: 1. Pre-Museum Visit Writing Lesson Taught by Classroom Teacher School & 2. Art and Writing Tour at the Museum Taught by Museum Docents Teacher 3. Post-Museum Visit Art-Making Activity Taught by Art Teacher 4. Post-Museum Visit Writing Lesson Taught by Classroom Teacher Programs The Wadsworth Atheneum requires a minimum of three weeks advanced booking for school tours. It is advised that teachers book and confirm their visit before administering the program’s lesson plans to students. Call our Group Visit Associate at (860) 838-4046 to reserve your Figuratively Speaking Art and Writing tour today. Be sure to mention that you are utilizing these pre- and post-museum visit curriculum materials when making your call. -

ART in Embassies Exhibition Vienna, Austria Sean Cavanaugh Young and Naked, 2008 Oil on Canvas, 16 X 16 In

ART in Embassies Exhibition Vienna, Austria Sean Cavanaugh Young and Naked, 2008 Oil on canvas, 16 x 16 in. (40,6 x 40,6 cm) Courtesy of the artist, New York, New York ART in Embassies ART in Embassies (ART) is a unique blend of art, diplomacy, and culture. Regardless of the medium, style, or subject matter, art transcends barriers of language and provides the means for the program to promote dialogue through the international language of art that leads to mutual respect and understanding between diverse cultures. Modestly conceived in 1963, ART has evolved into a sophisticated program that curates exhibitions, managing and exhibiting more than 3,500 original works of loaned art by U.S. citizens. The work is displayed in the public rooms of some 200 U.S. embassy residences and diplomatic missions worldwide. These exhibitions, with their diverse themes and content, represent one of the most important principles of our democracy: freedom of expression. The art is a great source of pride to U.S. ambassadors, assisting them in multi-functional outreach to the host country’s educational, cultural, business, and diplomatic communities. Works of art exhibited through the program encompass a variety of media and styles, ranging from eighteenth century colonial portraiture to contemporary multi-media installations. They are obtained through the generosity of lending sources that include U.S. museums, galleries, artists, institutions, corporations, and private collections. In viewing the exhibitions, the thousands of guests who visit U.S. embassy residences each year have the opportunity to learn about our nation – its history, customs, values, and aspirations – by experiencing firsthand the international lines of communication known to us all as art.