The Upper Cray Valley Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School Transport & Travel Guide 2020-2021

SCHOOL TRANSPORT & TRAVEL GUIDE 2020-2021 WELCOME FIVE STAR SERVICE Dear Parent, All of our vehicles are modern, easy-to-board and are operated by the Thank you for your interest in our School made on a termly basis for regular travel, and ad- school or one of our audited coach operators. This means that they are Transport services. This guide for the 2020- hoc travel is paid for at the time of booking. all regularly maintained to the highest standard, giving you peace of mind 21 academic year provides information on the that your daughter is travelling in safety. wide range of travel options available to pupils at All of our school minibuses are maintained to Bromley High School and I hope you will find it of a high standard and equipped with seatbelts at use. every seat. We use friendly, DBS checked drivers who have all undertaken the MiDAS minibus or This year we are proposing to increase the size professional driving qualifications. As we expand We use dedicated drivers who work on the same route each day. These of our network in response to demand and our service this year we will also be using larger drivers get to know the pupils and are subject to an enhanced disclosure changing travel habits. We continue to follow all coaches on the most popular routes. These will be and barring service (DBS) check. government guidance for the safe operation of under contract from local providers who will have our services including measures to ensure that we to demonstrate that they provide the same level are COVID secure; services may have to change of professional standards and safety. -

A History of Darwin's Parish Downe, Kent

A HISTORY OF DARWIN’S PARISH DOWNE, KENT BY O. J. R. HOW ARTH, Ph.D. AND ELEANOR K. HOWARTH WITH A FOREWORD BY SIR ARTHUR KEITH, F.R.S. SOUTHAMPTON : RUSSELL & CO. (SOUTHERN COUNTIES) LTD. CONTENTS CHAP. PAGE Foreword. B y Sir A rthur K eith, F.R.S. v A cknowledgement . viii I Site and P re-history ..... i II T he E arly M anor ..... 7 III T he Church an d its R egisters . 25 IV Some of t h e M inisters ..... 36 V Parish A ccounts and A ssessments . 41 VI T he People ....... 47 V II Some E arly F amilies (the M annings and others) . - 5 i VIII T he L ubbocks, of Htgh E lms . 69 IX T he D arwtns, of D own H ouse . .75 N ote on Chief Sources of Information . 87 iii FOREWORD By S ir A rth u r K e it h , F.R .S. I IE story of how Dr. Howarth and I became resi T dents of the parish of Downe, Kent— Darwin’s parish— and interested in its affairs, both ancient and modern, begins at No. 80 Wimpole Street, the home of a distinguished surgeon, Sir Buckston Browne, on the morning of Thursday, September 1, 1927. On opening The Times of that morning and running his eye over its chief contents before sitting down to breakfast, Sir Buck ston observed that the British Association for the Ad vancement of Science—of which one of the authors of this book was and is Secretary— had assembled in Leeds and that on the previous evening the president had delivered the address with which each annual meeting opens. -

Green Chain Walk – Section 6 of 11

Transport for London.. Green Chain Walk. Section 6 of 11. Oxleas Wood to Mottingham. Section start: Oxleas Wood. Nearest stations Oxleas Wood (bus stop on Shooters Hill / A207) to start: or Falconwood . Section finish: Mottingham. Nearest stations Mottingham to finish: Section distance: 3.7 miles (6.0 kilometres). Introduction. Walk in the footsteps of royalty as you pass Eltham Palace and the former hunting grounds of the Tudor monarchs who resided there. The manor of Eltham came into royal possession on the death of the Bishop of Durham in 1311. The parks were enclosed in the 14th Century and in 1364 John II of France yielded himself to voluntary exile here. In 1475 the Great Hall was built on the orders of Edward IV and the moat bridge probably dates from the same period. Between the reigns of Edward IV and Henry VII the Palace reached the peak of its popularity, thereafter Tudor monarchs favoured the palace at Greenwich. Directions. To reach the start of this section from Falconwood Rail Station, turn right on to Rochester Way and follow the road to Oxleas Wood. Enter the wood ahead and follow the path to the Green Chain signpost. Alternatively, take bus route 486 or 89 to Oxleas Wood stop and take the narrow wooded footpath south to reach the Green Chain signpost. From the Green Chain signpost in the middle of Oxleas Wood follow the marker posts south turning left to emerge at the junction of Welling Way and Rochester Way. Cross Rochester Way at the traffic lights and enter Shepherdleas Wood. -

Mottingham Station

Mottingham Station On the instruction of London and South Eastern Railway Limited Retail Opportunity On the instruction of LSER Retail Opportunity MOTTINGHAM STATION SE9 4EN The station is served by services operated by Southeastern to London Charing Cross, London Cannon Street, Woolwich Arsenal and Dartford. The station is located in the town on Mottingham. Location Rent An opportunity exists to let a unit at the front of We are inviting offers for this temporary opportunity. Mottingham railway station on Station Approach. Business plans detailing previous experience with visuals should be submitted with the financial offer. Description The unit is approximately 220sq ft and has 32amp power. The site does not have water & drainage and Business Rates is not suitable for catering. The tenant shall be responsible for business rates. A Information from the Office of the Rail Regulator search for the Rateable Value using the station stipulates that in 2019/20 there were over 1.322 postcode and the Valuation Office Agency website has million passenger entries and exits per annum. not provided any detail. It is recommended that interested parties make their own enquiries with the Local Authority to ascertain what business rates will Agreement Details be payable. We are inviting offers from retailers looking to trade Local Authority is London Borough of Greenwich. on a temporary basis documented by a Tenancy at Will. Other Costs The tenant will be responsible for all utilities, business We are not able to discuss longer term potential rates and insurance. currently. The Tenancy at Will will cost £395 plus vat. AmeyTPT Limited and their clients give notice that: (i) These particulars do not form part of any offer or contract and must not be relied upon as statements or representations of fact. -

Index Archives 1-10 1979 to 1988

ORPINGTON & DISTRICT ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY INDEX TO ARCHIVES VOLUMES 1-10 (1979-1988) INTRODUCTION This index comprises the ODAS Newsletter and Volumes 1-10 of Archives. My thanks go to Carol Springall, Michael Meekums and Hazel Shave for compiling this index. If you would like copies of any of these articles please contact Michael Mcekums. For information the ODAS Newsletters were published from 1975-1978 and the indexing shows this. Regarding Archives, the following table gives the year in which each Volume was published: Volume I published 1979 Volume 2 " 1980 Volume 3 " 1981 Volume 4 " 1982 Volume 5 " 1983 Volume 6 " 1984 Volume 7 II 1985 Volume 8 " 1986 Volume 9 " 1987 Volume 10 " ]988 When using the index please note the following points: 1. TIle section titles are for ease of reference. 2. "Fordcroft" and "Poverest" are sites at the same location. 3. "Crofton Roman Villa" is sometimes referred to as "Orpington Roman Villa" and "Villa Orpus''. To be consistent we have indexed it as "Crofton Roman Villa". Brenda Rogers Chairman rG Orpington & District Archaeological Society 1998 ARCHIVES AGM REPORTS Volume~umber/Page 5th AGM - 1978 1.1,7 6th AGM - 1979 2,1,8 7th A("M - 1980 3,1,14 8th AGM - 1981 4,1,7 9th AGM - 1982 5,1,10 IOth AGM - 1983 6,1,74 11th AGM - 1984 7,1,10 12th AGM - 1985 8,1,6 13th AGM - 1986 9,1,2 14th AGM - 1987 10,1,2 BlJRIALS Romano- Blitish Orpington, Fordcroft 3,1,13 May Avenue 3,1,13 Ramsden Road 3,1,13 Poverest 5,1,8 ......................................................... -

All London Green Grid River Cray and Southern Marshes Area Framework

All River Cray and Southern Marshes London Area Framework Green Grid 5 Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 8 Area Description 9 Strategic Context 10 Vision 12 Objectives 14 Opportunities 16 Project Identification 18 Project Update 20 Clusters 22 Projects Map 24 Rolling Projects List 28 Phase Two Early Delivery 30 Project Details 48 Forward Strategy 50 Gap Analysis 51 Recommendations 53 Appendices 54 Baseline Description 56 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA05 Links 58 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA05 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www.london.gov.uk/publication/all-london- green-grid-spg . -

Bod Agenda and Papers Feb 02 2016

AGENDA Meeting Board of Directors Time of meeting 09:30-12:30 Date of meeting Tuesday, 02 February 2016 Meeting Room Dulwich Room, Hambleden Wing Site King’s College Hospital, Denmark Hill Members: Lord Kerslake (BK) Trust Chair Christopher Stooke (CS) Non-Executive Director Faith Boardman (FB) Non-Executive Director Sue Slipman (SS) Non-Executive Director, Vice Chair Prof. Ghulam Mufti (GM1) Non-Executive Director Prof. Jonathan Cohen (JC) Non-Executive Director Dr Alix Pryde (AP) Non-Executive Director Erik Nordkamp (EN) Non-Executive Director Nick Moberly (NM) Chief Executive Officer Dawn Brodrick (DB) Director of Workforce Development Colin Gentile (CG) Chief Financial Officer Alan Goldsman (AG) Acting Director of Strategic Development Steve Leivers (SL) – Non-voting Director Director of Transformation and Turnaround Ahmad Toumadj (AT) – Non-voting Director Interim Director of Capital, Estates and Facilities Jeremy Tozer (JT) Interim Chief Operating Officer Dr. Geraldine Walters (GW) Director of Nursing & Midwifery Attendees: Tamara Cowan (TC) Board Secretary (Minutes) Sally Lingard (SL) Associate Director of Communications Fiona Clark (FC) Public Governor Paul Donohoe (PD) Deputy Medical Director Anne Duffy (AD) Divisional Head of Nursing Apologies: Trudi Kemp (TK) – Non-voting Director Director of Strategy Prof. Julia Wendon (JW) Medical Director Judith Seddon (JS) Acting Director of Corporate Affairs Circulation List: Board of Directors & Attendees Encl. Lead Time 1. S TANDING ITEMS Chair 09:30 1.1. Apologies 1.2. Declarations of Interest 1.3. Chair’s Action 1.4. Minutes of Previous Meeting – 15/12/2015 FA Enc. 1.4 1.5. Matters Arising FE Enc. 1.5 2. FOR REPORT 2.1. -

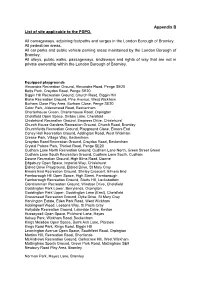

Appendix B List of Site Applicable to the PSPO. All Carriageways

Appendix B List of site applicable to the PSPO. All carriageways, adjoining footpaths and verges in the London Borough of Bromley. All pedestrian areas. All car parks and public vehicle parking areas maintained by the London Borough of Bromley. All alleys, public walks, passageways, bridleways and rights of way that are not in private ownership within the London Borough of Bromley. Equipped playgrounds Alexandra Recreation Ground, Alexandra Road, Penge SE20 Betts Park, Croydon Road, Penge SE20 Biggin Hill Recreation Ground, Church Road, Biggin Hill Blake Recreation Ground, Pine Avenue, West Wickham Burham Close Play Area, Burham Close, Penge SE20 Cator Park, Aldersmead Road, Beckenham Charterhouse Green, Charterhouse Road, Orpington Chelsfield Open Space, Skibbs Lane, Chelsfield Chislehurst Recreation Ground, Empress Drive, Chislehurst Church House Gardens Recreation Ground, Church Road, Bromley Churchfields Recreation Ground, Playground Close, Elmers End Coney Hall Recreation Ground, Addington Road, West Wickham Crease Park, Village Way, Beckenham Croydon Road Recreation Ground, Croydon Road, Beckenham Crystal Palace Park, Thicket Road, Penge SE20 Cudham Lane North Recreation Ground, Cudham Lane North, Green Street Green Cudham Lane South Recreation Ground, Cudham Lane South, Cudham Downe Recreation Ground, High Elms Road, Downe Edgebury Open Space, Imperial Way, Chislehurst Eldred Drive Playground, Eldred Drive, St Mary Cray Elmers End Recreation Ground, Shirley Crescent, Elmers End Farnborough Hill Open Space, High Street, Farnborough -

Dog Control Orders Clean Neighbourhoods and Environment Act 2005

Dog Control Orders Clean Neighbourhoods and Environment Act 2005 The Clean Neighbourhoods and Environment Act 2005 The Dog Control Orders (Prescribed offences and Penalties, etc) Regulations 2006 (SI 2006/1059) THE FOULING OF LAND BY DOGS (London Borough of Bromley) ORDER 2010 The London Borough of Bromley makes the following Order: 1. The Order will come into force on the seventh day of April 2010 2. This Order applies to the land specified in Schedule 1 Offence 3. (1) If a dog defecates at any time on land to which this Order applies and a person who is in charge of the dog at that time fails to remove the faeces forthwith, that person shall be guilty of an offence unless - a) he has reasonable excuse for failing to do so; or b) the owner occupier or other person or authority having control of the land has consented (generally or specifically) to his failing to do so. (2) Nothing in this article applies to a person who – a) is registered as a blind person in a register complied under section 29 of the National Assistance Act 1948; or b) has a disability which affects his mobility, manual dexterity, physical co-ordination or ability to lift, carry or otherwise move everyday objects, in respect of a dog trained by a prescribed charity and upon which he relies for assistance. (3) For the purposes of this article – a) a person who habitually has a dog in his possession shall be taken to be in charge of the dog at any time unless at that time some other person is in charge of the dog; b) placing the faeces in a receptacle on the land which is provided for the purpose, or for the disposal of waste, shall be a sufficient removal from the land; c) being unaware of the defecation (whether by reason of not being in the vicinity or otherwise), or not having a device for or other suitable means of removing the faeces shall not be a reasonable excuse for failing to remove the faeces; d) each of the following is a “prescribed charity” – i. -

Richard Kilburne, a Topographie Or Survey of The

Richard Kilburne A topographie or survey of the county of Kent London 1659 <frontispiece> <i> <sig A> A TOPOGRAPHIE, OR SURVEY OF THE COUNTY OF KENT. With some Chronological, Histori= call, and other matters touching the same: And the several Parishes and Places therein. By Richard Kilburne of Hawk= herst, Esquire. Nascimur partim Patriæ. LONDON, Printed by Thomas Mabb for Henry Atkinson, and are to be sold at his Shop at Staple-Inn-gate in Holborne, 1659. <ii> <blank> <iii> TO THE NOBILITY, GEN= TRY and COMMONALTY OF KENT. Right Honourable, &c. You are now presented with my larger Survey of Kent (pro= mised in my Epistle to my late brief Survey of the same) wherein (among severall things) (I hope conducible to the service of that Coun= ty, you will finde mention of some memorable acts done, and offices of emi= <iv> nent trust borne, by severall of your Ancestors, other remarkeable matters touching them, and the Places of Habitation, and Interment of ma= ny of them. For the ready finding whereof, I have added an Alphabeticall Table at the end of this Tract. My Obligation of Gratitude to that County (wherein I have had a comfortable sub= sistence for above Thirty five years last past, and for some of them had the Honour to serve the same) pressed me to this Taske (which be= ing finished) If it (in any sort) prove servicea= ble thereunto, I have what I aimed at; My humble request is; That if herein any thing be found (either by omission or alteration) substantially or otherwise different from my a= foresaid former Survey, you would be pleased to be informed, that the same happened by reason of further or better information (tend= ing to more certaine truths) than formerly I had. -

Plans Sub-Committee No.3 Tuesday 9 May 2017 Decision Sheet

PLANS SUB-COMMITTEE NO.3 TUESDAY 9 MAY 2017 DECISION SHEET PLEASE NOTE: Set out below is a brief indication of the decisions made by the Plans Sub-Committee No. 3 on Tuesday 9 May 2017. For further details of the conditions, reasons, grounds, informatives or legal agreements, it is necessary to see the Minutes. The description of the development remains as it was presented to the Sub-Committee unless otherwise stated. Agenda Item No. and Title of Report Decision Action Ward By 1 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE All Members present AND NOTIFICATION OF SUBSTITUTE MEMBERS 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST None 3 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES Confirmed OF MEETING HELD ON 16 MARCH 2017 Section 1 (Applications submitted by the London Borough of Bromley) 0.1 (17/01039/ADV) - Land At Junction ADVERTISEMENT Chief Copers Cope With High Street Rectory Road, CONSENT GRANTED Planner Conservation Area Beckenham Section 2 (Applications meriting special consideration) 4.2 (16/05881/FULL1) - 4 Pleydell REFUSED Chief Crystal Palace Avenue, Anerley, London, SE19 Planner 2LP 4.3 (17/00256/FULL6) - 124 Copse DEFERRED Chief West Wickham Avenue, West Wickham, BR4 9NP Planner 4.4 (17/00435/FULL1) - Land Adjoining PERMISSION Chief Crystal Palace Grace House, Sydenham Avenue, Planner Sydenham, London 4.5 (17/00884/FULL6) - 250 Upper PERMISSION SUBJECT Chief Kelsey and Eden Park Elmers End Road, Beckenham, TO SECTION 106 Planner/ BR3 3HE. AGREEMENT CEX Section 3 (Applications recommended for permission, approval or consent) 4.6 (16/05229/FULL1) - 130 Croydon PERMISSION Chief Crystal Palace Road, Penge, London, SE20 7YZ Planner London Borough of Bromley – Decisions taken by Plans Sub-Committee No. -

![Lullingstone Roman Villa. a Teacher's Handbook.[Revised]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0520/lullingstone-roman-villa-a-teachers-handbook-revised-380520.webp)

Lullingstone Roman Villa. a Teacher's Handbook.[Revised]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 445 970 SO 031 609 AUTHOR Watson, lain TITLE Lullingstone Roman Villa. A Teacher's Handbook. [Revised]. ISBN ISBN-1-85074-684-2 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 44p. AVAILABLE FROM English Heritage, Education Service, 23 Savile Row, London W1X lAB, England; Tel: 020 7973 3000; Fax: 020 7973 3443; E-mail: [email protected]; Web site: (www.english-heritage.org.uk/). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archaeology; Foreign Countries; Heritage Education; *Historic Sites; Historical Interpretation; Learning Activities; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *England (Kent); English History; Mosaics; *Roman Architecture; Roman Civilization; Roman Empire; Site Visits; Timelines ABSTRACT Lullingstone, in Kent, England, is a Roman villa which was in use for almost the whole period of the Roman occupation of Britain during the fourth century A.D. Throughout this teacher's handbook, emphasis is placed on the archaeological evidence for conclusions about the use of the site, and there are suggested activities to help students understand the techniques and methods of archaeology. The handbook shows how the site relates to its environment in a geographical context and suggests how its mosaics and wall paintings can be used as stimuli for creative work, either written or artistic. It states that the evidence for building techniques can also be examined in the light of the technology curriculum, using the Roman builder activity sheet. The handbook consists of the following sections: