Transitional Justice and Reconciliation in the Western Balkans: Approaches, Impacts and Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Mladić Plaque in East Sarajevo

Mladić Plaque in East Sarajevo: A Continuation of the Genocide In June there were reports that a commemorative plaque honoring Ratko Mladić had been installed in the hills above Sarajevo. When I returned to Sarajevo from Srebrenica, where I had witnessed the 19th annual commemorative burials of the victims of the genocide on July 11, I made plans to locate the commemorative plaque. I had to see it, as one says, with my own eyes. The plaque is located, as is the park, on Vraca Hill, just above Grbavica. The plaque was installed in a wall that borders Vraca Memorial Park, a park that commemorates the citizens of Sarajevo who died during World War II.1 As one climbs by car on Derviša Numića Street above Grbavica, a road sign announces that one is leaving Sarajevo Canton, and another sign announces that one is entering the Town of East Sarajevo, which is located within Republika Srpska. The plaque is on the left side of the road, just another 50 meters further ahead. In April 1992, the memorial park was seized by the Bosnian Serbs for its value as strategic high ground from which to attack the city of Sarajevo.2 The terraces of the memorial park extend to the northeast, looming above the city, and according to news reports as well as indictments based on eye- witness accounts, the park offered a position from which snipers could terrorize the citizens of Sarajevo.3 According to my sources there was a tank position located approximately 150 meters to the west of the park along Teočačka Street. -

Sarajevo Redux: Socio-Spatial Outcomes and the Perpetuation of Fragility in a Post- Conflict City

Sarajevo Redux: Socio-Spatial Outcomes and the Perpetuation of Fragility in a Post- Conflict City James Schmitt Supervisor: Prof. Günter Meinert Supervisor: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Philipp Misselwitz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Urban Management at Technische Universität Berlin Berlin, 1st of February 2019 Statement of authenticity of material This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any institution and to the best of my knowledge and belief, the research contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text of the thesis. James D. Schmitt Berlin, 1 February 2019 Abstract In an increasingly urbanized world, new constructs concerning urban fragility, the changed nature and increasing urbanization of armed conflict and emerging conceptual frameworks for urban post-conflict interventions present new discourses for urban planners and post-conflict first responders to consider. Cities with the highest level of fragility tend to be in states destabilized by ongoing intrastate conflict and yet even after negotiated peace settlements recovering cities appear particularly vulnerable to the accumulation of urban risks and tensions associated with higher levels of urban fragility. Working as part of an international post-conflict intervention recovery effort, how can urban planners contribute to achieving better long-term outcomes of peace and stability in the urban post-conflict setting? By conducting a macro and meso level case study analysis of Sarajevo's international post- conflict intervention through the lens of the social contract, liberal peace, and collective memory theoretical frameworks, this thesis seeks to identify strategic approaches and outcomes of Sarajevo's post-conflict intervention process and the related long-term impacts of these outcomes at the municipal and neighborhood scale. -

Intercultural Dialogue, Peacebuilding, Constructive Remembrance and Reconciliation

A TOOLKIT FOR TEACHERS IN THE WESTERN BALKANS EDUCATING FOR INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE, PEACEBUILDING, CONSTRUCTIVE REMEMBRANCE AND RECONCILIATION 2019 2 Educating for Intercultural Dialogue, Peacebuilding, Constructive Remembrance and Reconciliation: A Toolkit for Teachers in the Western Balkans Prepared by Dr. Sara Clarke-Habibi © 2019 UNICEF Albania and RYCO This toolkit is produced in the framework of the “Supporting the Western Balkan's Collective Leadership on Reconciliation” a joint UN-RYCO project, funded by the UN Peacebuilding Fund. It is implemented by the Regional Youth Cooperation Office (RYCO) and the three UN Agencies – UNDP, UNFPA, and UNICEF. The project aims to build capacities and momentum for RYCO, empower young people in having their voice in public decision- making that affects their lives, as well as strengthen them to be a factor in building and maintaining safe and peaceful environments for themselves and their communities This activity contributes to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals. Cover Photo credit: UNICEF Kosovo Innovations Lab The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of UNICEF. 3 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................ 4 Introduction ............................................................................. 5 Why is this resource needed? ............................................................................ 5 Objectives -

Download PDF (13.1

Table of content 1 Preface 2 Introduction Manual 5 Exercises 6 1. What is a Monument to you? 7 2. My View, your View 10 3. Monument Charades 11 4. Challenges of Monument-building 13 5. Biography of a Monument 14 Memory Walk Reading Guide 15 6. Memory Walk Filmclips 16 7. One Monument, Ten Opinions 17 Actor Cards 19 8. My Ideal Monument 20 9. Debating Monuments 21 10. Local Monuments Tour 22 11. Oral History of a Monument 23 The Story of Memory Walk 23 Background of the Concept 27 Sample Memory Walk Program 28 Video-commentaries HIP 29 Sarajevo/East-Sarajevo, BiH 33 Zagreb, Croatia 36 Skopje, Macedonia 39 Belgrade, Serbia 43 Memory Walk Library 46 Acknowledgements Preface This manual is one of the key teaching resources developed in the project 'Historija, Istorija, Povijest - Lessons for Today.' This project was launched in 2015 by the Anne Frank House, in cooperation with local partner organizations from Croatia (Croatian Education and Development Network for the Evolution of Communication - HERMES), Bosnia-Herzegovina (Youth Initiative for Human Rights-YIHR and Humanity in Action- HIA), Serbia (Open Communication - OK) and Macedonia (Youth Educational Forum - MOF). We had big goals - to raise awareness and encourage discussion about the recent history of nationalism, exclusion, prejudice, discrimination in the region and promote debate and dialogue on our common past. We also wanted to promote critical thinking about historical events and their relevance for contemporary challenges, as well as to inspire an interdisciplinary, civic-education oriented history education. This project builds upon the mission of the Anne Frank House, an independent organization that is entrusted with the care of the place where Anne Frank went into hiding during World War II and where she wrote her diary. -

59Th Report of the High Representative for Implementation of the Peace Agreement on Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Secretary- General of the United Nations

59th report of the High Representative for Implementation of the Peace Agreement on Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Secretary- General of the United Nations Summary This report covers the period from 16 October 2020 through 15 April 2021. After more than one year since the global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) is in the midst of the latest wave of infection, with daily new cases and deaths from the virus at an all-time high, especially in the region of the capital Sarajevo. Restrictive measures, including curfews, have been reintroduced in most areas. Vaccines have only been trickling in, largely through donations, and a coordinated immunization effort is still in the very early stages. As of 15 April, there have been a reported total of ca. 182,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection and ca. 7,250 deaths from virus in BiH since the first outbreak last year. Though it must be noted that BiH is hardly alone in the world in terms of experiencing difficulties in procuring vaccines and rolling out a vaccination program, the pandemic nonetheless continues to reveal serious dysfunctionality in the country, whereby political leaders and authorities in BiH too frequently sacrifice a unified and coordinated approach to combating the pandemic and easing its impact on the population and the economy in favor of scoring political points against one another. This has led to a situation in which, in the absence of measures pursued by the relevant State-level authorities, the entities have taken unilateral and uncoordinated measures, resulting in different solutions being undertaken in different parts of the territory of BiH. -

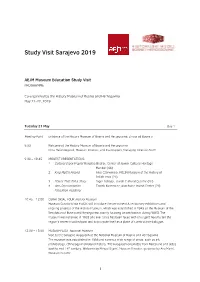

Programme Sarajevo Study Visit 2019

Study Visit Sarajevo 2019 AEJM Museum Education Study Visit TENTATIVE PROGRAMME Co-organized by the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina May 21-22, 2019 Tuesday 21 May Day 1 Meeting Point Entrance of the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Zmaja od Bosne 5 9:00 Welcome at the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina Elma Hašimbegović, Museum Director, and Eva Koppen, Managing Director AEJM 9:30 – 10:45 PROJECT PRESENTATIONS 1. Cultural Diary Project Marjetka Bedrac, Center of Jewish Cultural Heritage Maribor (SK) 2. King Matt’s Poland Ania Czerwinska, POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews (PL) 3. Places That Tell a Story Inger Schaap, Jewish Cultural Quarter (NL) 4. Anti-Discrimination Tomek Kuncewicz, Auschwitz Jewish Center (PL) Education Academy 10:45 – 12:00 CURATORIAL TOUR History Museum Museum Curator Elma Hodžić will introduce the permanent & temporary exhibitions and ongoing projects of the History Museum, which was established in 1945 as the Museum of the Revolution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, mainly focusing on antifascism during WWII. The museum was renamed in 1993 and ever since has been faced with an urgent need to tell the region’s recent troubled past and to promote itself as a place of constructive dialogue. 12:00 – 13:00 MUSEUM VISIT National Museum Visit to the Sarajevo Haggadah at the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The museum was established in 1888 and covers a wide range of areas, such as art, archaeology, ethnology and natural history. The Haggadah originates from Barcelona and dates back to mid 14th century. Welcome by Mirsad Sijarić, Museum Director, guidance by Ana Marić, Museum Curator 1 13:00 – 14:00 LUNCH BREAK Optional Bosnian Sephardic lunch will be served by Miryam Tauber of the NGO Association Haggadah. -

ESITIS Conf Welcome Letter with Information

March 2019 Dear participant, It is my pleasure to welcome you next month to the 2019 ESITIS Conference and to Sarajevo, Bosnia & Herzegovina. Below you find some information for planning your visit. Feel free to contact me with any concerns or questions. Please make sure to register using the attached form and by paying the conference fee (locals are exempt from this fee) by 1 April. An opening reception on 24 April and lunches on 25 and 26 April plus coffee/tea breaks for the whole conference are included in your conference fee. Please let me know as soon as possible if you have any dietary needs. On your conference registration form you were asked to mark your interest in our optional excursion to Mostar on 28 April. Some information is included below, and the cost of the tour will follow. Please let me know by 1 April if you did not express interest but would like to join. We will also offer two afternoon city tours of Sarajevo on 26 April, which will cost approximately 10 KM per person (5 euros). Please let me know asap if you wish to join a city tour and specify which one you prefer (see info below). If you are presenting a paper at the conference, the convener of your session (see call for papers) will be in contact about details. Projectors and attached computers with internet will be available. If you are interested to publish your paper, ESITIS’ journal, Interreligious Studies and Intercultural Theology, please contact the editors, Nelly van Doorn-Harder and Paul Hedges with your abstract (see https://journals.equinoxpub.com/isit). -

Press Kit Lara Ciarabellini Somnambulism

New Release Lara Ciarabellini SOMNAMBULISM Authors: Šefik Daupovi ć Fiko, Christian Elia, Edin Forto, Andjel - ka Klemen čić, Paul Lowe, Samanta Milio, Tomo Novosel, Dino Pora Porovi ć, Francesca Rolandi Artist: Lara Ciarabellini Hardcover 28 x 30 cm 144 pages 86 color- and b/w-ills. English ISBN 978-3-86828-622-9 Euro 39,90 Impressive photographic observations about the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina 20 years after the end of the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Exhibitions Somnambulism discusses the importance of culture and urban Novi Hram Gallery, Sarajevo fabric in the construction-destruction-reconstruction of the 02. – 12.07.2015 country. In four different stages, the reader will experience a metaphorical wandering of night and day walking between the Photon Gallery, Ljubljana old and new infrastructures, buildings and monuments. Firstly, 21. – 27.09.2015 in a once-upon-a-time journey between Sarajevo and Belgrade, historical events unfold the Yugoslav intercultural nation born La casa del Design (ADI), Milan after the World War II. Then, landscapes still offended by the tra - 13. – 21.10.2015 gedy of the war and of the urbicide, reveal the collective amne - sia of the 1992 – 1995 conflict. In the last two stages, the dua - lism between division and unity betoken the contemporary ter - rain of Bosnia and Herzegovina, marked both by the visible pre - sence of religious monuments and by landscapes which uprise to avoid the oblivion of the multicultural common past. With her photographs, Lara Ciarabellini is able to show the chan - ge in the web of intertwining layers of the Yugoslav and Bosnian collective memory in the last decades, adding a new and per - sonal point of view in the analysis of the aftermath of the war. -

Programme Sarajevo Study Visit 2019

Study Visit Sarajevo 2019 AEJM Museum Education Study Visit PROGRAMME Co-organized by the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina May 21-22, 2019 Tuesday 21 May Day 1 Meeting Point Entrance of the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Zmaja od Bosne 5 9:00 Welcome at the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina Elma Hašimbegović, Museum Director, and Eva Koppen, Managing Director AEJM 9:30 – 10:45 PROJECT PRESENTATIONS 1. Cultural Diary Project Marjetka Bedrac, Center of Jewish Cultural Heritage Maribor (SK) 2. King Matt’s Poland Ania Czerwinska, POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews (PL) 3. Places That Tell a Story Inger Schaap, Jewish Cultural Quarter (NL) 4. Anti-Discrimination Tomek Kuncewicz, Auschwitz Jewish Center (PL) Education Academy 10:45 – 12:00 CURATORIAL TOUR History Museum Museum Curator Elma Hodžić will introduce the permanent & temporary exhibitions and ongoing projects of the History Museum, which was established in 1945 as the Museum of the Revolution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, mainly focusing on antifascism during WWII. The museum was renamed in 1993 and ever since has been faced with an urgent need to tell the region’s recent troubled past and to promote itself as a place of constructive dialogue. 12:00 – 13:00 MUSEUM VISIT National Museum Visit to the Sarajevo Haggadah at the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The museum was established in 1888 and covers a wide range of areas, such as art, archaeology, ethnology and natural history. The Haggadah originates from Barcelona and dates back to mid 14th century. Welcome by Mirsad Sijarić, Museum Director, guidance by Ana Marić, Museum Curator 1 13:00 – 14:00 LUNCH BREAK Optional Bosnian Sephardic lunch will be served by Miryam Tauber of the NGO Association Haggadah. -

The Lessons from the Past — the Tools for the Future

The lessons from the past — the tools for the future MemorInmotion Pedagogical tool / Trainings of the trainers on culture of remembrance Documentation / Evaluation 2015 The lessons from the past — the tools for the future MemorInmotion Pedagogical tool / Trainings of the trainers on culture of remembrance Documentation / Evaluation Copyright @ Forum Ziviler Friedensdienst e.V. (forumZFD) 2015 Contents 1. Introduction 06 2. Summary of the trainings 10 2.1. Additional impressions by team of trainers of the teacher training pedagogical tool on the 14 culture remembrance ‘MemorInmotion’. 3. Reflection on the implentation of pedagogical tool “MemorInmotion” 17 3.1. Comments of the participants in a training who implemented the pedagogical tool 18 ‘MemorInmotion’ in the field 3.2. Rating of pedagogical tool based on the received feedback of the implemeted 40 Tool in the field 4. Creating active culture of memories through invigorating teachers: Encouraging the 42 young through critical pedagogy and peace education – Larisa Kasumagić-Kafedžić 5. Recommendations for further work 48 6. Biographies 50 7. Thanks to 51 8. Annex 52 1. Introduction 1. Introduction After the invitation for future trainers was published in mid February 2015 through Mreža mira (Peace network), the young people to critically think about the process of memorialization, e.g. through contextualization the pedagogical tool “MemorInmotion” came to life. In the course of 2014, experts of BiH association of of a strategy of preserving memories and raising awareness about the -

Maja Musi Department of History – Ghent University, Belgium

Maja Musi Department of History – Ghent University, Belgium Tangled memories. Sarajevo’s Vraca Memorial Park and the reconstruction of the past in Bosnia and Herzegovina. My aim in this paper is that of presenting the case of a memorial complex in the city of Sarajevo, to explore how remembrance of different events is shaped around one single site, implicitly or explicitly, and what implications these different layers of memory have for the study of public discourses and practices of memory and identity in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina. Though limited to a specific case, the paper tries to highlight some features from which the study of memory in a post-socialist and post-war context can benefit. Contextualization In the framework of extreme (ethno)nationalist ideologies fostered by the political elites of the parties involved in the war marking the end of Socialist Yugoslavia, cultural heritage acquired a place within the list of targets for destruction. While nationalist rhetoric juxtaposed ethnic affiliations within a logic of mutually exclusive definitions of self and other based on blood purity, political projects of ethnic homogenization on given territories were pursued with violent means between 1992 and 1995 in the republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Efforts of redrawing the territorial organization and demographic composition of the area were carried out using systematic violence against the ethnic other through practices ranging from harassment to deportation, torture, rape, detention in camps and mass !" " killings, where the Serb faction assumed by and large the role of the perpetrator. Within this context, narratives of the past were employed to stiffen ethnic affiliations as well as justify current political and military goals. -

Ethnic Cleansing in Republika Srpska

London School of Economics and Political Science Sara Maria de Morais Bettencourt da Câmara Correia REMEMBERING ETHNIC CLEANSING IN REPUBLIKA SRPSKA An Ethnography of Memory in the City of Bijeljina A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government London School of Economics September 2018 1 Abstract This thesis provides a case-study of the relationship between public memory and lived experience in the process of transformation of national identity in the aftermath of 'ethnic cleansing'. Once a multiethnic town with a Muslim majority, since the 1992-1995 Bosnian war the town of Bijeljina has been subjected to dynamics that resulted in the imposition of a narrow interpretation of Serb national identity in the public space. In this liminal process, Bijeljina has been transformed into a 'Serb' town, where Muslims are now tolerated but marginalised. 'Ethnic cleansing', the ultimate liminal experience, was central to the transformation of Bijeljina, and it figures prominently in the recollections of the local population, but is virtually absent from official memory, which is submitted to the demands of the nationalist agenda of the local authorities. An ethnographic approach allowed me to go beyond public representations, to explore private aspects of social memory and how these interact with official memory, as people try to find meaning for their wartime experience. I combined my observation of everyday life through immersion in the community during one year of fieldwork with in-depth interviews focusing on the respondents' recollections of life before the war, their wartime experience, how they reorganised their lives once the war was over, how they see the present and imagine a future for themselves and their families.