Heritage Conservation Through Planning: a Comparison of Policies and Principles in England and China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BP the Architect and River

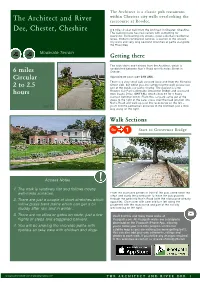

Uif!Bsdijufdu!jt!b!dmbttjd!qvc!sftubvsbnu! xjuijn!Diftufs’t!djuz!xbmmt!pwfsmppljnh!uif! Uif!Bsdijufdu!bne!Sjwfs! sbdfdpvstf!bu!Sppeff/ Eff-!Diftufs-!Diftijsf A 6 mile circular walk from the Architect in Chester, Cheshire. The walking route has real variety with something for everyone: the bustling city streets, quiet suburban residential lanes, modern commercial estates, a section of the ancient city walls and very long peaceful stretches of paths alongside the River Dee. Moderate Terrain Hfuujnh!uifsf The walk starts and finishes from the Architect, which is sandwiched between Nun’s Road and Nicholas Street in 7!njmft! Chester. Djsdvmbs!!!! Approximate post code CH1 2NX. There is a very small pub car park accessed from the Nicholas Street side, but whilst you are completing the walk please use 3!up!3/6! one of the public car parks nearby. The easiest is Little Roodee Car Park (alongside Grosvenor Bridge and accessed ipvst from Castle Drive, CH1 1SL) which costs £3 for 3 hours (correct Summer 2013). From this car park come out of the steps to the right of the cafe, cross over the road junction into Nun’s Road and walk up past the racecourse on the left – 210114 you’ll find the pedestrian entrance to the Architect just a little way along on the right. Wbml!Tfdujpnt Go 1 Tubsu!up!Hsptwfnps!Csjehf Access Notes 1. The walk is relatively flat and follows mostly well-made surfaces. From the courtyard garden in front of the pub, come down the steps and along the paved path to leave the pub grounds 2. -

Sat 05 - Sun 13 // Sept 15

1 Future Heritage 5 RE:NEW Uncovered What could future buildings in Chester look like? It’s up to Before work began on Chester’s major new cultural centre, us to decide! Archaeologists uncovered vital information about Chester’s Join us for a fun event to explore what might replace the old Roman history. Come and discover the thrill of seeing Quick’s Garage on Lower Bridge St in Chester. artefacts that have not seen the light of day for almost two All you need is your imagination – we’ll supply pens for you thousand years! to sketch your ideas on the back of this leaflet. Or come with Drop in anytime or meet the archaeologists on Thursday. your designs for us to display. Prizes for the best ideas! Venue: 49-51 Northgate St. Venue: 15 Bridge Street Row (above the Pound Bakery ) Date / Time: Mon 7th - Fri 11th between 10.00 - 16.00 Date / time: Sat 5th. Drop in between 10am-4pm Meet the archaeologists: Thu 10th 12.00 - 14.30 Contact: 01244 343 772 Contact: 01244 976212 2 Grosvenor Park park 6 Chester City Walls If you are curious about the recent restoration of the park, Would you like to learn more about our famous city walls? why not join our guided tour which will take in the Edward Drop in to the award winning restoration of King Charles Kemp landscape and the wonderful new café in the Grade II Tower to learn first hand how the hard working team look listed Lodge . after our Roman City Walls. -

ARCHITECTURE, ARCHAEOLOGY and CONTEMPORARY CITY PLANNING «Issues of Scale»

ARCHITECTURE, ARCHAEOLOGY AND CONTEMPORARY CITY PLANNING «Issues of Scale» LONDON 22-25th September 2016 London, UK 22-25th September 2016 ARCHITECTURE, ARCHAEOLOGY AND CONTEMPORARY CITY PLANNING “Issues of scale” PROCEEDINGS editors: James Dixon Giorgio Verdiani Per Cornell Published on May 2017 London, UK 22-25th September 2016 Scholar workshop: ARCHITECTURE, ARCHAEOLOGY AND CONTEMPORARY CITY PLANNING The workshop took place in London, U+I Offices, 7a Howick Place, Victoria. Workshop organizing committee: James Dixon, Giorgio Verdiani, Per Cornell The workshop has been realized in collaboration between Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), the Architecture Department of the Florence University, Italy, the Department of Historical Studies, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Proceedings Editors: James Dixon, Giorgio Verdiani, Per Cornell [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] Scientists participating at the workshop: Per Cornell, James Dixon, Liisa Seppänen, Giorgio Verdiani, Matteo Scamporrino, Pia Englund, Anna Frank, Louise Armstrong, Nick Woodford, Valentina Fantini, Laura Polizzi, Neil Korostoff, Oliver Brown, Gwilym Williams, Sophie Jackson, Valerio Massaro, Sabrina Morreale, Ludovica Marinaro, Timothy Murtha, Thomson Korostoff, Giulio Mezzetti, Sarah Jones, Natalie Cohen, Francesco Maria Listi, Katrina Foxton. PROCEEDINGS INDEX INDEX WORKSHOP PRESENTATION James Dixon, Per Cornell, Giorgio Verdiani ............................................................................... 7 VIRTUAL RESEARCH -

11 Days Guizhou Guilin Ethnic Culture Tour with Li River Cruise

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 11 days Guizhou Guilin ethnic culture tour with Li River cruise https://windhorsetour.com/guizhou-tour/guizhou-guilin-tour-with-li-river-cruise Guiyang Anshun Kaili Rongjiang Congjiang Zhaoxing Sanjiang Longsheng Guilin Yangshuo Guilin This south China tour balances an ethnic discovery in Guizhou province and a Li River cruise from Guilin to Yangshuo. Endless natural landscapes await to be found. Added with a cultural visit to the ethnic minorities in Guizhou and Guilin. Type Private Duration 11 days Trip code GE-03 Price From ¥ 9,500 per person Itinerary This tour combines an ethnic cultural trip in Guizhou province and a memorable Guilin Li River cruise. Enjoy a wonderful time by viewing the spectacular scenery of the largest waterfall in Asia, Huangguoshu Waterfall. Experience the lifestyle of Miao and Dong ethnic minorities by visiting their villages. At the end of this tour you will have a cruise along the Li River from Guilin to Yangshuo. Immerse yourself into the unspoiled landscapes and more. Your journey is full of memories. Day 01 : Arrive Guiyang As the entrance point of this ethnic tour, Guiyang, the capital of Guizhou province, is home to more than 30 minority ethnic groups including Miao, Buyi, Dong and Hui. Upon your arrival at the airport or railway station, be assisted by your local guide and then get settled into the downtown hotel for a short break. After having lunch at the hotel, drive to the Qingyan ancient town located in the southern suburb of Guiyang city. As one of the most famous historical and cultural towns in Guizhou province, Qingyan was first built in 1378 as a station for transferring military messages and to house a standing army. -

BP the Old Harkers Arms and Chester City Trail.Pages

Uif!Pme!Ibslfst!Bsnt!jt!b!qspqfs!pme!djuz! pg!Mpnepn!cpp{fs-!pnmz!jn!Diftufs-!uibu!jt! Uif!Pme!Ibslfst!Bsnt!bne! tfu!dmptf!up!uif!dpnnfsdjbm!bne! Diftufs!Djuz!Usbjm-! qspgfttjpnbm!ifbsu!pg!uif!djuz/! A 3 mile circular pub walk from the Old Harkers Arms in Chester, Cheshire. The walking route follows a trail exploring Diftufs-!Diftijsf some of the highlights that the city offers – the canal towpath, the old city walls, the famous racecourse, the River Dee and several of Chester’s beautiful parks. Easy Terrain Hfuujnh!uifsf! The walk starts and finishes from the Old Harkers Arms, on Russell Street (directly alongside the canal) in Chester. Approximate post code CH3 5AL. The pub does not have a car park, so if you are coming by car you’ll need to park in one 4!njmft! of the paid car parks in Chester. The nearest ones are the rail station car park (CH1 3NS) and Browns Yard car park on Bold Djsdvmbs!!!!! Place, off York Street (CH1 3LZ). 3!ipvst! Wbml!Tfdujpnt! Go 1 Tubsu!up!Wbufs!Upxfs! 230815 To begin the walk, stand with your back to the pub (which at one time was a canal-boat chandlers run by a Mr Harker) facing the Shropshire Union Canal and turn left along the towpath, with the canal on your right. You will pass under the City Road bridge after just a few paces and, as you approach Access Notes the next bridge, keep to the right on the path alongside the canal which passes under it. -

Project Ethnic Minority Development

Ethnic Minority Development Plan November 2017 PRC: Guiyang Integrated Water Resources Management (Sector) Project Ethnic Minority Development Plan for the Hongyan Reservoir and Associated Waterworks Subproject Prepared by Guiyang Water Resources & Transport Development & Investment (Group) Co. Ltd. for the Asian Development Bank. This ethnic minority development plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ADB-funded Guiyang Integrated Water Resources Management (Sector) Project (Loan 2573-PRC) Ethnic Minority Development Plan for the Hongyan Reservoir and Associated Waterworks Subproject (Updated) Guiyang Water Resources & Transport Development & Investment (Group) Co., Ltd. November 2017 Table of Contents Revision Statement ............................................................................................................................................. a Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................ b 1. Introduction -

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, Vol. 10.2

LINGUISTIG OF THE TIBETO-BURMANAREA James A. Matisolf. Editor University of California. Berkeley EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Paul L BENEDICT Nicholas C. BODMAN Brkrcliff Manor. NY Cornell University David BRADLEY Scott DE LANCET La Trobe University. University 01 Oregon Melbourne. Australia Inga-LiIi HANSSON F-K. LEHMAN Uniwrsity of Lund. Sweden University al Illinois Martine WAZAUDON Boyd MICHAILOVSW Centre National pour la Centre National pour ia Recherche Scientilique. Paris Recherche Scientifique. Paris Graham THURGOOD Julian t;. WHEATLEY CaliIornia Stale University, Cornell University Fresno ! 010 -LCCN 022 - LSSN 050 - Call number (LC) I OCLC number: 4790670 FROM TJ3E EDITOR This issue of LTBA is devoted entirely to the fascinating and understudied Hrnong-Mien (Miao-Yao] language family. Many of the articles date from a panel on Hmong Language and Linguistics chaired by David Strecker during the Southeast Asian Studies Summer Institute ISEASSI) Conference at the University of Michigan in the summer of 1985. Later several papers on Mien (by Caron. Court, Pumell. and Solnit) were added. along with last-minute conlributions by Lyman and Jaisser. The end reult is a well-rounded set of papers that cover a range of synchronic and diachronic topics in Hmong-Mien phonology. grammar. and orthography. We would like to thank DavId Strecker and Brenda Johns for conceiving this idea of a special issue on Hmong-Mien. Tanya Smith was ably assisted in the prepamtion of the manuscripts by Steve Baron. Amy Dolcourt. John Lowe. and Jean McAneny. to all of whom many thanks. A curnulathre index to the Brst ten volumes of LTBA appears on pp. 177- 180. -

Spatiotemporal Dynamic Analysis of A-Level Scenic Spots in Guizhou Province, China

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Spatiotemporal Dynamic Analysis of A-Level Scenic Spots in Guizhou Province, China Yuanhong Qiu 1,2, Jian Yin 1,2,3,*, Ting Zhang 1, Yiming Du 1 and Bin Zhang 1,2 1 College of Big Data Application and Economic, Guizhou University of Finance and Economics, Huaxi District, Guiyang 550025, China; [email protected] (Y.Q.); [email protected] (T.Z.); [email protected] (Y.D.); [email protected] (B.Z.) 2 Center for China Western Modernization, Guizhou University of Finance and Economics, Huaxi District, Guiyang 550025, China 3 School of Water Conservancy and Civil Engineering, Northeast Agricultural University, Xiangfang District, Harbin 150050, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: A-level scenic spots are a unique evaluation form of tourist attractions in China, which have an important impact on regional tourism development. Guizhou is a key tourist province in China. In recent years, the number of A-level scenic spots in Guizhou Province has been increasing, and the regional tourist economy has improved rapidly. The spatial distribution evolution characteristics and influencing factors of A-level scenic spots in Guizhou Province from 2005 to 2019 were measured using spatial data analysis methods, trend analysis methods, and geographical detector methods. The results elaborated that the number of A-level scenic spots in all counties of Guizhou Province increased, while in the south it developed slowly. From 2005 to 2019, the spatial distribution in A-level scenic spots were characterized by spatial agglomeration. The spatial distribution equilibrium degree Citation: Qiu, Y.; Yin, J.; Zhang, T.; of scenic spots in nine cities in Guizhou Province was gradually developed to reach the “relatively Du, Y.; Zhang, B. -

Crossing Boundaries.Indb

This pdf of your paper in Crossing Boundaries belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (May 2020), unless the site is a limited access intranet (password protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books (editorial@ oxbowbooks.com). Frontispiece: Professor Emeritus Richard N. Bailey, OBE: ‘in medio duorum’ (Photo: Alison Bailey) AN OFFPRINT FROM CROSSING BOUNDARIES INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACHES TO THE ART, MATERIAL CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE OF THE EARLY MEDIEVAL WORLD Edited by ERIC CAMBRIDGE AND JANE HAWKES Essays presented to Professor Emeritus Richard N. Bailey, OBE, in honour of his eightieth birthday Hardcover Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-307-2 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-308-9 (epub) © Oxbow Books 2017 Oxford & Philadelphia www.oxbowbooks.com Published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by OXBOW BOOKS The Old Music Hall, 106–108 Cowley Road, Oxford, OX4 1JE and in the United States by OXBOW BOOKS 1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083 © Oxbow Books and the individual authors 2017 Hardcover Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-307-2 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-308-9 (epub) A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bailey, Richard N., honouree. | Cambridge, Eric, editor. | Hawkes, Jane (Medievalist), editor. Title: Crossing boundaries : interdisciplinary approaches to the art, material culture, language and literature of the early medieval world : essays presented to Professor Emeritus Richard N. -

Civilizational Spread and Ethnic Fusion: Analysis of the Impact of Bureaucratization of Native Officers in Guizhou Region During Ming and Qing Dynasties

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 10, No. 1, 2014, pp. 48-55 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020141001.4228 www.cscanada.org Civilizational Spread and Ethnic Fusion: Analysis of the Impact of Bureaucratization of Native Officers in Guizhou Region During Ming and Qing Dynasties JIANG Mengmei[a],*; LUAN Chengbin[b] [a]School of History and Culture & School of Ethnology, Southwest JIANG Mengmei, LUAN Chengbin (2014). Civilizational Spread and University, Chongqing, China. Ethnic Fusion: Analysis of the Impact of Bureaucratization of Native [b]Institute of History & Geography, Southwest University, Chongqing, Officers in Guizhou Region During Ming and Qing Dynasties. Cross- China. Cultural Communication, 10(1), 48-55. Available from: http//www. *Corresponding author. cscanada.net/index.php/ccc/article/view/j.ccc.1923670020141001.4228 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020141001.4228 Received 6 October 2013; accepted 23 January 2014 Abstract Bureaucratization of native officers is a major event in the INTRODUCTION history of Guizhou region, which went through the Ming Before the Ming and Qing dynasties, central and Qing dynasties. In fact, this process is also a province governments of various dynasties based their policy of establishing process during which the civilizations of governing Guizhou on the “loose control” Jimi system. central plains and minority groups interacted and fused After the establishment of the Ming dynasty, in order together, and the territory of Guizhou province was to prevent the repetition of history, i.e. Mongol Yuan’s gradually settled. Bureaucratization of native officers detour to Yunnan to take Southern Song dynasty by in Guizhou is a systematic project which replaced surprise, the rulers managed Guizhou as the strategic the economic bases under different social systems area for controlling southwest China, especially Yunnan. -

8. Bibliography for Resource Assessment (Pdf)

Bibliography Bibliography Abramson P, 2000, ‘A re-examination of a Viking Age burial at and a Frontier Vicus. Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquar- Beacon Hill, Aspatria’, TTCWAAS 100, 79-88. ian and Archaeological Society Research Series No 6. Kendal. Adams M H, 1995, An archaeological evaluation at St Chad’s Church, Bailey R N, 1977a, ‘A cup-mount from Brougham, Cumbria,’ Kirkby, Knowsley, Merseyside. Liverpool Museum unpublished Med Archaeol 21, 176-80. report. Bailey R N, 1977b, ‘The meaning of the Viking-age shaft at Da- Adams M H & Philpott, R A, forthcoming, A Romano-British and cre’, TCWAAS 77, 61-74. later site at Court Farm, Halewood, Merseyside. Bailey R N, 1980, Viking Age sculpture in northern England. London. Addyman P V, Simpson W G & Spring P W H, 1963, ‘Two me- Bailey R N, 1984, ‘Irish Sea contacts in the Viking Period - the dieval sites near Sedbergh, West Riding’, YAJ 41, 27-42. sculptural evidence’, in Fellows-Jensen G & Lund N (eds), Alcock L, 1972, ‘By South Cadbury is that Camelot.....’: excavations at Tredie Tvaerfaglige Vikingesyposium, 1-36. Copenhagen. Cadbury Castle 1966-70. London. Bailey R N, 1994, ‘Govan and Irish Sea sculpture’, in Ritchie A Alebon P H, Davey P J & Robinson D J, 1976, ‘The Eastgate, (ed), Govan and its early medieval sculpture, 113-21. Stroud. Chester 1972’, JCAS 59, 37-49. Bailey R N, 1996, England’s earliest sculptors. Toronto. Allan J P, 1984, Medieval and Post-Medieval Finds from Exeter, 1971- Bailey R N, 2003, ‘‘What mean these stones?’. Some aspects of 1980. Exeter, Exeter Archaeological Reports III. -

Archaeological Journal on the Age of the City Walls Of

This article was downloaded by: [Northwestern University] On: 09 February 2015, At: 19:29 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Archaeological Journal Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raij20 On the Age of the City Walls of Chester George W. Shrubsole F.G.S. Published online: 15 Jul 2014. To cite this article: George W. Shrubsole F.G.S. (1887) On the Age of the City Walls of Chester, Archaeological Journal, 44:1, 15-25, DOI: 10.1080/00665983.1887.10852249 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1887.10852249 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.