Camelot and the World of PG Wodehouse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Westminster Abbey South Quire Aisle

Westminster Abbey South Quire Aisle The Dedication of a Memorial Stone to P G Wodehouse Friday 20th September 2019 6.15 pm HISTORICAL NOTE It is no bad thing to be remembered for cheering people up. As Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (1881–1975) has it in his novel Something Fresh, the gift of humour is twice blessed, both by those who give and those who receive: ‘As we grow older and realize more clearly the limitations of human happiness, we come to see that the only real and abiding pleasure in life is to give pleasure to other people.’ Wodehouse dedicated almost 75 years of his professional life to doing just that, arguably better—and certainly with greater application—than any other writer before or since. For he never deviated from the path of that ambition, no matter what life threw at him. If, as he once wrote, “the object of all good literature is to purge the soul of its petty troubles”, the consistently upbeat tone of his 100 or so books must represent one of the largest-ever literary bequests to human happiness by one man. This has made Wodehouse one of the few humourists we can rely on to increase the number of hours of sunshine in the day, helping us to joke unhappiness and seriousness back down to their proper size simply by basking in the warmth of his unique comic world. And that’s before we get round to mentioning his 300 or so song lyrics, countless newspaper articles, poems, and stage plays. The 1998 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary cited over 1,600 quotations from Wodehouse, second only to Shakespeare. -

An Eden with No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in The

An Eden With No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in the English Novel by Joshua Gibbons Striker Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Victor Strandberg, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Kathy Psomiades ___________________________ Michael Moses Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT An Eden With No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in the English Novel by Joshua Gibbons Striker Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Victor Strandberg, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Kathy Psomiades ___________________________ Michael Moses An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Joshua Gibbons Striker 2019 Abstract In this dissertation I use an old and unfashionable form of literary criticism, close reading, to offer a new and unfashionable account of the literary subgenre called camp. Drawing on the work of, among many others, Susan Sontag, Rita Felski, and Peter Lamarque, I argue that P.G. Wodehouse, E.F. Benson, and Angela Thirkell wrote a type of pure comedy I call chaste camp. Chaste camp is a strange beast. On the one hand it is a sort of children’s literature written for and about adults; on the other hand it rises to a level of literary merit that children’s books, even the best of them, cannot hope to reach. -

Summer 2007 Large, Amiable Englishman Who Amused the World by DAVID MCDONOUGH

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 28 Number 2 Summer 2007 Large, Amiable Englishman Who Amused the World BY DAVID MCDONOUGH ecently I read that doing crossword puzzles helps to was “sires,” and the answer was “begets.” In Right Ho, R ward off dementia. It’s probably too late for me (I Jeeves (aka Brinkley Manor, 1934), Gussie Fink-Nottle started writing this on my calculator), but I’ve been giving interrogates G. G. Simmons, the prizewinner for Scripture it a shot. Armed with several good erasers, a thesaurus, knowledge at the Market Snodsbury Grammar School and my wife no more than a phone call away, I’ve been presentations. Gussie, fortified by a liberal dose of liquor- doing okay. laced orange juice, is suspicious of Master Simmons’s bona I’ve discovered that some of Wodehouse’s observations fides. on the genre are still in vogue. Although the Egyptian sun god (Ra) rarely rears its sunny head, the flightless “. and how are we to know that this has Australian bird (emu) is still a staple of the old downs and all been open and above board? Let me test you, acrosses. In fact, if you know a few internet terms and G. G. Simmons. Who was What’s-His-Name—the the names of one hockey player (Orr) and one baseball chap who begat Thingummy? Can you answer me player (Ott), you are in pretty good shape to get started. that, Simmons?” I still haven’t come across George Mulliner’s favorite clue, “Sir, no, sir.” though: “a hyphenated word of nine letters, ending in k Gussie turned to the bearded bloke. -

The World of Blandings: (Blandings Castle) Free

FREE THE WORLD OF BLANDINGS: (BLANDINGS CASTLE) PDF P. G. Wodehouse | 656 pages | 20 Jun 2011 | Cornerstone | 9780099514244 | English | London, United Kingdom The World of Blandings (Blandings) by P G Wodehouse A Blandings Omnibus In this wonderfully fat omnibus, which seems to span the dimensions of the Empress of Blandings herself the fattest pig in Shropshire and surely all Englandthe whole world of Blandings Castle is spread out for our delectation: the engagingly dotty Lord Emsworth and his enterprising brother Galahad, his terrifying sister Lady Constance, Beach the butler his voice 'like tawny port made audible'James Wellbeloved, the gifted but not always sober pigman, and Lord Emsworth's secretary the Efficient Baxter, with gleaming spectacles, whose attempts to bring order to the Castle always end in disarray. Lurking in the wings is Sir Gregory Parsloe-Parsloe of Matchingham Hall, the neighbour with designs on the Prize which must surely belong to the The World of Blandings: (Blandings Castle). As Evelyn Waugh wrote, 'The gardens of Blandings Castle are that original garden from which we are all exiled. Each time you read another Blandings story, the sublime nature of that world is such as to make you gasp. It's dangerous to use the word genius to describe a writer, but I'll risk it with him. Not only the funniest English novelist who ever wrote but one of our finest stylists. For as long as I'm immersed in a P. Wodehouse book, it's possible to keep the real world at bay and live in a far, far nicer, funnier one where happy endings are the order of the day. -

Know Your Audience: Middlebrow Aesthetic and Literary Positioning in the Fiction of P.G

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Einhaus, Ann-Marie (2016) Know Your Audience: Middlebrow aesthetic and literary positioning in the fiction of P.G. Wodehouse. In: Middlebrow Wodehouse: P.G. Wodehouse's Work in Context. Ashgate, Farnham, pp. 16-33. ISBN 9781472454485 Published by: Ashgate URL: This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/25720/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) PLEASE NOTE: This is the typescript of the published version of ‘Know your audience: Middlebrow aesthetic and literary positioning in the fiction of P.G. -

Autumn-Winter 2002

Beyond Anatole: Dining with Wodehouse b y D a n C o h en FTER stuffing myself to the eyeballs at Thanks eats and drinks so much that about twice a year he has to A giving and still facing several days of cold turkey go to one of the spas to get planed down. and turkey hash, I began to brood upon the subject Bertie himself is a big eater. He starts with tea in of food and eating as they appear in Plums stories and bed— no calories in that—but it is sometimes accom novels. panied by toast. Then there is breakfast, usually eggs and Like me, most of Wodehouse’s characters were bacon, with toast and marmalade. Then there is coffee. hearty eaters. So a good place to start an examination of With cream? We don’t know. There are some variations: food in Wodehouse is with the intriguing little article in he will take kippers, sausages, ham, or kidneys on toast the September issue of Wooster Sauce, the journal of the and mushrooms. UK Wodehouse Society, by James Clayton. The title asks Lunch is usually at the Drones. But it is invariably the question, “Why Isn’t Bertie Fat?” Bertie is consistent preceded by a cocktail or two. In Right Hoy Jeeves, he ly described as being slender, willowy or lissome. No describes having two dry martinis before lunch. I don’t hint of fat. know how many calories there are in a martini, but it’s Can it be heredity? We know nothing of Bertie’s par not a diet drink. -

Aunts Aren't What?

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 27 Number 3 Autumn 2006 Aunts Aren’t What? BY CHARLES GOULD ecently, cataloguing a collection of Wodehouse novels in translation, I was struck again by R the strangeness of the title Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen and by the sad history that seems to dog this title and its illustrators, who in my experience always include a cat. Wodehouse’s original title is derived from the dialogue between Jeeves and Bertie at the very end of the novel, in which Bertie’s idea that “the trouble with aunts as a class” is “that they are not gentlemen.” In context, this is very funny and certainly needs no explication. We are well accustomed to the “ungentlemanly” behavior of Aunt Agatha—autocratic, tyrannical, unreasoning, and unfair—though in this instance it’s the good and deserving Aunt Dahlia whose “moral code is lax.” But exalted to the level of a title and thus isolated, the statement A sensible Teutonic “aunts aren’t gentlemen” provokes some scrutiny. translation First, it involves a terrible pun—or at least homonymic wordplay—lost immediately on such lost American souls as pronounce “aunt” “ant” and “aren’t” “arunt.” That “aunt” and “aren’t” are homonyms is something of a stretch in English anyway, and to stretch it into a translation is hopeless. True, in “The Aunt and the Sluggard” (My Man Jeeves), Wodehouse wants us to pronounce “aunt” “ant” so that the title will remind us of the fable of the Ant and the Grasshopper; but “ants aren’t gentlemen” hasn’t a whisper of wit or euphony to recommend it to the ear. -

Wodehouse and the Baroque*1

Connotations Vol. 20.2-3 (2010/2011) Worcestershirewards: Wodehouse and the Baroque*1 LAWRENCE DUGAN I should define as baroque that style which deli- berately exhausts (or tries to exhaust) all its pos- sibilities and which borders on its own parody. (Jorge Luis Borges, The Universal History of Infamy 11) Unfortunately, however, if there was one thing circumstances weren’t, it was different from what they were, and there was no suspicion of a song on the lips. The more I thought of what lay before me at these bally Towers, the bowed- downer did the heart become. (P. G. Wodehouse, The Code of the Woosters 31) A good way to understand the achievement of P. G. Wodehouse is to look closely at the style in which he wrote his Jeeves and Wooster novels, which began in the 1920s, and to realise how different it is from that used in the dozens of other books he wrote, some of them as much admired as the famous master-and-servant stories. Indeed, those other novels and stories, including the Psmith books of the 1910s and the later Blandings Castle series, are useful in showing just how distinct a style it is. It is a unique, vernacular, contorted, slangy idiom which I have labeled baroque because it is in such sharp con- trast to the almost bland classical sentences of the other Wodehouse books. The Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary describes the ba- roque style as “marked generally by use of complex forms, bold or- *For debates inspired by this article, please check the Connotations website at <http://www.connotations.de/debdugan02023.htm>. -

Download Plum Pie, , P. G. Wodehouse, Overlook Press, 2008

Plum Pie, , P. G. Wodehouse, Overlook Press, 2008, 1590200101, 9781590200100, 319 pages. DOWNLOAD HERE Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves , Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, 1963, Fiction, 224 pages. In this humorous take on English manners, the paragon of British gentlemanly virtues leaps to the aid of his bumbling batchelor boss on numerous occasions.. The Most Of P.G. Wodehouse , P.G. Wodehouse, Nov 1, 2000, Fiction, 672 pages. Presents a collection of humorous stories, including "The Truth about George," "Ukridge's Dog College," "The Coming of Gowf," "The Purity of the Turf," and "A Slice of Life.". Lord Emsworth Acts for the Best The Collected Blandings Short Stories, P. G. Wodehouse, 1992, , 181 pages. Noveller fra samlingerne: Blandings Castle, Lord Emsworth and others, Nothing serious og Plum pie.. The Old Reliable , Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, 1951, , 233 pages. Jeeves And The Tie That Binds , P.G. Wodehouse, Nov 1, 2000, Fiction, 208 pages. After saving his master so often in the past, Jeeves may finally prove to be the unwitting cause of Bertie Wooster's undoing when the Junior Ganymede, a club for butlers in .... Money in the bank , Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, 1964, , 239 pages. A few quick ones , Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, 1978, Fiction, 207 pages. Do butlers burgle banks? , Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, Jan 1, 1979, Fiction, 158 pages. Right Ho, Jeeves , P. G. Wodehouse, Jan 1, 2008, Fiction, 212 pages. Please visit www.ManorWodehouse.com to see the complete selection of P. G Wodehouse books available in the Manor Wodehouse Collection.. The Cat-Nappers , P. G. Wodehouse, Feb 1, 1990, , 190 pages. Assigned by his Aunt Dahlia to cat-nap the good-luck companion of a racehorse against which she has bet heavily, Bertie Wooster enlists the assistance of his valet, Jeeves, in ... -

“Across the Pale Parabola of Joy”: Wodehouse Parodist

Connotations Vol. 13.1-2 (2003/2004) “Across the pale parabola of Joy”: Wodehouse Parodist INGE LEIMBERG In his stories and novels Wodehouse never comments on his tech- nique but, fortunately, in his letters to Bill Townend, the author friend who first introduced him to Stanley Featherstonaugh Ukridge, he does drop some professional hints, for instance: I believe there are two ways of writing novels. One is mine, making the thing a sort of musical comedy without music, and ignoring real life alto- gether; the other is going right down into life and not caring a damn. (WoW 313) This is augmented by a later remark concerning autobiographic inter- pretations, especially of Shakespeare: A thing I can never understand is why all the critics seem to assume that his plays are a reflection of his personal moods and dictated by the circum- stances of his private life. […] I can’t see it. Do you find that your private life affects your work? I don’t. (WoW 360) In 1935, when he confessed to “ignoring real life altogether,” Wode- house had found his form. Looking at his work of some 25 years before, we can get an idea of how he did so. In Psmith Journalist (1912), for instance, that exquisite is indeed concerned with real life, but, ten years later, in Leave it to Psmith, he joins the Blandings gang and, finally, replaces the efficient Baxter as Lord Emsworth’s secretary, with hardly a trace of real life left in him. Opening one of Wodehouse’s best stories or novels is like saying, “Open Sesame!” or “Curtain up!” and from then on, in a way, nothing is but what is not. -

By the Way Sept 08.Qxd

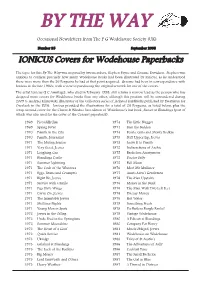

BY THE WAY Occasional Newsletters from The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Number 35 September 2008 IONICUS Covers for Wodehouse Paperbacks The topic for this By The Way was inspired by two members, Stephen Payne and Graeme Davidson. Stephen was anxious to confirm precisely how many Wodehouse books had been illustrated by Ionicus, as he understood there were more than the 56 Penguins he had at that point acquired. Graeme had been in correspondence with Ionicus in the late 1980s, with a view to purchasing the original artwork for one of the covers. The artist Ionicus (J C Armitage), who died in February 1998, still retains a narrow lead as the person who has designed more covers for Wodehouse books than any other, although this position will be surrendered during 2009 to Andrzej Klimowski, illustrator of the Collectors series of jacketed hardbacks published by Everyman (or Overlook in the USA). Ionicus provided the illustrations for a total of 58 Penguins, as listed below, plus the wrap-around cover for the Chatto & Windus first edition of Wodehouse’s last book, Sunset at Blandings (part of which was also used for the cover of the Coronet paperback). 1969 Piccadilly Jim 1974 The Little Nugget 1969 Spring Fever 1974 Sam the Sudden 1970 Psmith in the City 1974 Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin 1970 Psmith, Journalist 1975 Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves 1971 The Mating Season 1975 Leave It to Psmith 1971 Very Good, Jeeves 1975 Indiscretions of Archie 1971 Laughing Gas 1975 Bachelors Anonymous 1971 Blandings Castle 1975 Doctor Sally 1971 Summer Lightning -

Convention Time: August 11–14

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 26 Number 2 Summer 2005 Convention Time: August 11–14 nly two months to go, but it’s not too late to send farewell brunch Oin your registration for The Wodehouse Society’s Fun times that include reading stories with 13th International Convention, Hooray for Hollywood! other Wodehousians, visiting booksellers’ The site of this year’s gathering is Sunset Village on the and Chapters Corner tables, plenty of grounds of the UCLA campus, a beautiful location singing, and most of all cavorting with with easy access to Westwood, the Getty Museum, and fellow Plummies from all over so much more. And if you’re worried about the climate, don’t be: Informed sources tell us that we can expect What—you want to know more? Well, then, how warm, dry weather in Los Angeles in August, making about our speakers, who include: for an environment that will be pleasurable in every way. Brian Taves: “Wodehouse Still can’t make up your mind? Perhaps on Screen: Hollywood and these enticements will sway you: Elsewhere” Hilary & Robert Bruce: “Red A bus tour of Hollywood that Hot Stuff—But Where’s the includes a visit to Paramount Red Hot Staff?” (by Murray Studios Hedgcock) A Clean, Bright Entertainment Chris Dueker: “Remembrance of that includes songs, skits, and Fish Past” The Great Wodehouse Movie Melissa Aaron: “The Art of the Pitch Challenge Banjolele” Chances to win Exciting Prizes Tony Ring: “Published Works on that include a raffle, a Fiendish Wodehouse” Quiz based on Wodehouse’s Dennis Chitty: “The Master’s Hollywood, and a costume Beastly Similes” competition A weekend program that includes Right—you’re in? Good! Then let’s review erudite talks, more skits and what you need to know.