On Aging Into Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Queer Icon Penny Arcade NYC USA

Queer icON Penny ARCADE NYC USA WE PAY TRIBUTE TO THE LEGENDARY WISDOM AND LIGHTNING WIT OF THE SElf-PROCLAIMED ‘OLD QUEEn’ oF THE UNDERGROUND Words BEN WALTERS | Photographs DAVID EdwARDS | Art Direction MARTIN PERRY Styling DAVID HAWKINS & POP KAMPOL | Hair CHRISTIAN LANDON | Make-up JOEY CHOY USING M.A.C IT’S A HOT JULY AFTERNOON IN 2009 AND I’M IN PENNy ARCADE’S FOURTH-FLOOR APARTMENT ON THE LOWER EASt SIde of MANHATTan. The pink and blue walls are covered in portraits, from Raeburn’s ‘Skating Minister’ to Martin Luther King to a STOP sign over which Penny’s own image is painted (good luck stopping this one). A framed heart sits over the fridge, Day of the Dead skulls spill along a sideboard. Arcade sits at a wrought-iron table, before her a pile of fabric, a bowl of fruit, two laptops, a red purse, and a pack of American Spirits. She wears a striped top, cargo pants, and scuffed pink Crocs, hair pulled back from her face, no make-up. ‘I had asked if I could audition to play myself,’ she says, ‘And the word came back that only a movie star or a television star could play Penny Arcade!’ She’s talking about the television film, An Englishman in New York, the follow-up to The Naked Civil Servant, in which John Hurt reprises his role as Quentin Crisp. Arcade, a regular collaborator and close friend of Crisp’s throughout his last decade, is played by Cynthia Nixon, star of Sex PENNY ARCADE and the City – one of the shows Arcade has blamed for the suburbanisation of her beloved New York City. -

30 24 AWP Full Magazine

Read your local stoop inside. Read them all at BrooklynPaper.com Brooklyn’s Real Newspaper BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 834–9350 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2007 BROOKLYN HEIGHTS–DOWNTOWN EDITION AWP /18 pages • Vol. 30, No. 24 • Saturday, June 16, 2007 • FREE INCLUDING DUMBO BABY PRICEY SLICE BANDIT Piece of pizza soaring toward $3 Sunset Parker aids By Ariella Cohen The Brooklyn Paper orphaned raccoon A slice of pizza has hit $2.30 in Carroll Gardens — and the shop’s owner says it’s “just a matter of By Dana Rubinstein time” before a perfect storm of soaring cheese prices The Brooklyn Paper and higher fuel costs hit Brooklyn with the ultimate insult: the $3 slice. A Sunset Park woman is caring for a help- Sal’s Pizzeria, a venerable joint at the corner of less baby raccoon by herself because she Court and DeGraw streets, has punched a huge hole can’t find a professional to take over. in the informal guideline that the price of a slice “I’ve been calling for days, everywhere. I should mirror the price of a swipe on the subway. haven’t gotten no help from no one,” said Mar- Last week, owner John Esposito hung a sign in his garita Gonzalez, who has been feeding the cub front window blaming “an increase in cheese prices” with a baby bottle ever since it wandered into her for the sudden price hike from $2.15, which he set backyard on 34th Street near Fourth Avenue. last year. “I called the Humane Society, and from To bolster his case, Esposito also posted copies of there they have connected me to numbers and a typewritten “update” from his Wisconsin-based / Stephen Chernin cheese supplier, Grande Cheese, explaining that its prices had risen 35 cents a pound because of an “un- precedented” 18-percent spike in milk costs. -

Number 140 / Summer 2017 Conversations Between Artists

Conversations between Artists, Writers, Musicians, Performers, Directors—since 1981 BOMB $10 US / $10 CANADA FILE UNDER ART AND CULTURE DISPLAY UNTIL SEPTEMBER 15, 2017 Number 140 / Summer 2017 A special section in honor of John Giorno John Giorno in front of his Poem Paintings at the Bunker, 222 Bowery, New York City, 2012. Photo by Peter Ross. All images courtesy of the John Giorno Collection, John Giorno Archives, Studio Rondinone, New York City, 81 unless otherwise noted. John Giorno, Poet by Chris Kraus and Rebecca Waldron i ii iii (i) Giorno performing at the Nova Convention, 1978. Photo by James Hamilton. (ii) THANX 4 NOTHING, pencil on 82 paper, 8.5 × 8.5 inches. (iii) Poster for the Nova Convention, 1978, 22 × 17 inches. thanks for allowing me to be a poet electronically twisted and looped his own voice while a noble effort, doomed, but the only choice. reciting his poems. Freeing writing from the page, —John Giorno, THANX 4 NOTHING (2006) Giorno allowed his audiences to step into the physical space of his poems and strongly influenced techno- John Giorno’s influence as a cultural impresario, philan- punk music pioneers like the bands Suicide and thropist, activist, hero, and éminence grise stretches Throbbing Gristle. Yet it’s not Giorno’s use of technol- so widely and across so many generations that one ogy that makes his work memorable, but the sound can almost forget that he is primarily a poet. His work and texture of his voice. The artist Penny Arcade saw is a shining example of how, at their best, poems can him perform at the Poetry Project in 1969, and said, act as a form of public address. -

2017–2018 Annual Report

2017–2018 ANNUAL REPORT GREENWICH VILLAGE SOCIETY PRESERVING FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION OUR PAST, Trustees September 2018 President Mary Ann Arisman Ruth McCoy ENGAGING Arthur Levin Tom Birchard Andrew Paul Dick Blodgett Rob Rogers Vice Presidents Jessica Davis Katherine Schoonover Trevor Stewart Cassie Glover Marilyn Sobel OUR Kyung Choi Bordes David Hottenroth Judith Stonehill Anita Isola Naomi Usher Secretary/Treasurer John Lamb Linda Yowell FUTURE. Allan Sperling Justine Leguizamo F. Anthony Zunino Leslie Mason GVSHP Staff Andrew Berman Harry Bubbins Matthew Morowitz Executive Director East Village & Special Projects Program and Administrative Director Associate Sarah Bean Apmann Director of Research & Ariel Kates Sam Moskowitz Preservation Manager of Communications Director of Operations and Programming Lannyl Stephens Director of Development and Special Events Offices Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 | T: 212-475-9585 | www.gvshp.org Support GVSHP–become a member or make a donation: gvshp.org/membership Join our e-mail list for alerts and updates: [email protected] Visit our blog Off the Grid (gvshp.org/blog) Connect with GVSHP: Facebook.com/gvshp Flickr.com/gvshp Twitter.com/gvshp Instagram.com/gvshp_nyc YouTube.com/gvshp 3 A NOTE FROM THE PRESIDENT As Andrew Berman our Executive Director I am pleased to report that again this year GVSHP continues to grow by every measure of an reported at our 2018 Annual Meeting this past organization’s success. Especially gratifying is the steady growth in our membership and the critical June, “this has been a real watershed year financial, political and moral support members provide for the organization. -

Reviews & Press •

REVIEWS & PRESS J. Hoberman. On Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (and Other Secret-Flix of Cinemaroc). Granary Books, & Hip’s Road, 2001. • Grubbs, David. "Review of On Jack Smith's 'Flaming Creatures.' " Bookforum 9.1: 15. It's a shame that Ted Turner dropped out of the film-colorization business before tackling Flaming Creatures. I'm trying to imagine Jack Smith's washed-out, defiantly low-contrast 1963 film being given the full treatment. Flaming Creatures is the work for which Smith is best known, a film that landed exhibitors in a vortex of legal trouble and quickly became the most reviled of '60s underground features. As J. Hoberman writes, "Flaming Creatures is the only American avant-garde film whose reception approximates the scandals that greeted L'Age d'Or or Zéro de Conduite." Smith's self-described comedy in a "haunted movie studio" is a forty-two-minute series of attractions that include false starts, primping, limp penises, bouncing breasts, a fox-trot, an orgy, a transvestite vampire, an outsized painting of a vase, and perilous stretches of inactivity. The sound track juxtaposes Bartók, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, the Everly Brothers, and an audience-baiting minutes-long montage of screams. Still, one suspects that the greatest trespass may have been putting Smith's queer "creatures" on display. If Hoberman's monograph makes Smith's filmic demimonde less other-worldly—colorizes it, if without the Turner motive—it does so in a manner more akin to the 1995 restoration of Jacques Tati's 1948 Jour de Fête. Tati's film was shot simultaneously in color and in black and white; had the experimental Thomson-Color process worked at the time, it would have been the first French full-length color film. -

Italianità Alternativa Published on Iitaly.Org (

Italianità alternativa Published on iItaly.org (http://ftp.iitaly.org) Italianità alternativa Joey Skee* (January 28, 2010) “Who, or more precisely, what is an Italian American? To some self-appointed arbiters of italianità, the answer is: Roman Catholic, conservative, and indisputably heterosexual.” If we have learned anything from the ongoing scrutiny of the Italian-American “experience” it is that said experience is any thing but singular. Italian-American histories and cultures are diverse, multifaceted, and ever open to new interpretations and revisions. Author George De Stefano [2] began a 2001 book review in the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute’s social-science journal, the Italian American Review [3] (vol. 8, no.2), with a rhetorical question: “Who, or more precisely, what is an Italian American? To some self-appointed arbiters of italianità, the answer is: Roman Catholic, conservative, and indisputably heterosexual.” If we have learned anything from the ongoing scrutiny of the Italian-American “experience” it is that said experience is any thing but singular. Italian-American histories and cultures are diverse, multifaceted, and ever open to new interpretations and revisions. The Calandra Institute’s public programs offer an opportunity to recognize and represent the diverse expressions of an italianità alternativa. Page 1 of 5 Italianità alternativa Published on iItaly.org (http://ftp.iitaly.org) On October 6, 2009, John Giorno [4] read from his selected works Subduing Demons in America [5] (Soft Skull Press, 2008) as part of the Institute’s Writers Read series. Giorno founded the artist collective Giorno Poetry Systems [6] in 1968, which used technology to make poetry accessible to new audiences and influenced spoken word and slam poetry. -

Lower East Side, Nyc September 23 - October 16, 2011

MARKETLOWER EAST SIDE, NYC SEPTEMBER 23 - OCTOBER 16, 2011 OVER 40 GROUPS ORGANIZATIONS INDIVIDUALS & BUSINESSES URA HSpecial P S Seward Park Urban Section Renewal Area H Our ongoing investigation of the intersec- tion of art, labor, economics, and the produc- tion of unexpected social experiences has led us to initiate Introductionthis new project we call MARKET. The project creates space for direct conversations and reflections on the many diverse ways in which we make our world, and the kinds of social, economic, and cultural relationships we want to foster in our daily exchanges with others. [CONTINUED ON PAGE 3] FREE COMPLETE SCHEDULE PAGE 23 3 INTRODUCTION REVEREND BILLY AND THE CHURCH OF EAR- MUSEUM By Temporary Services THALUJAH 17 GOOD OLD LOWER EAST SIDE 4 PICTURE THE HOMELESS 11 CUCHIFRITOS LOWER EAST SIDE COMMUNITY THE TEETH OF THE ARCHIVE HESTER STREET COLLABORATIVE & SUPPORTED AGRICULTURE By Gregory Sholette and others THE WATERFRONT ON WHEELS THE LOWER EAST SIDE SQUATTER-HOME- CAKE SHOP BLUESTOCKINGS STEADER ARCHIVE PROJECT 5 PEOPS LOWER EAST SIDE PEOPLES’ FEDERAL CREDIT LIVING THEATRE By Fly UNION 18 COMMUNIST GUIDE TO NEW YORK CITY 6 HOUSE MAGIC BUREAU OF FOREIGN COR- 12 SPURA & THE CITY STUDIO By Yevgeniy Fiks RESPONDENCE Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani, Buscada & New School’s Urban Studies program ALPHABET CITY ACUPUNTURE DOWNTOWN COMMUNITY TELEVISION CENTER 14 BULLET SPACE CHIPPY DESIGN JIM’S PEPPER ROASTER DAMON RICH TZADIK HOWL! ARTS TIME’S UP! 19 SELECTED MUSIC FROM OR ABOUT THE LES 7 PLACE MATTERS 15 LOWER EASTSIDE GIRLS’ CLUB 20 ALLIED PRODUCTIONS LOWER EAST SIDE PRINTSHOP LOWER EAST SIDE HISTORY PROJECT SKIN BY KYRA 8 ABC NO RIO 16 LOCAL SPOKES ANTON VAN DALEN [CONTINUED P. -

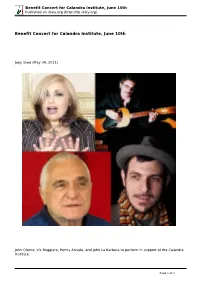

Benefit Concert for Calandra Institute, June 10Th Published on Iitaly.Org (

Benefit Concert for Calandra Institute, June 10th Published on iItaly.org (http://ftp.iitaly.org) Benefit Concert for Calandra Institute, June 10th Joey Skee (May 09, 2011) John Giorno, Vic Ruggiero, Penny Arcade, and John La Barbera to perform in support of the Calandra Institute. Page 1 of 3 Benefit Concert for Calandra Institute, June 10th Published on iItaly.org (http://ftp.iitaly.org) BENEFIT CONCERT Friday, June 10, 2011, 6 pm John D. Calandra Italian American Institute 25 West 43rd Street, 17th floor between 5th and 6th Avenues Please join us for an exciting evening of performances to benefit the Calandra Institute and its journal Italian American Review. Enjoy music and spoken word as presented by world- renowned artists John Giorno, Vic Ruggiero, Penny Arcade, and John La Barbera. Wine and refreshments will be served. The Calandra Institute is the only academic research institute in the country dedicated to the study of Italian-American history and culture. In the past five years, we have introduced ever more engaging scholarly and cultural programming for your appreciation. The more recent additions to our unique offerings include the newly relaunched journal Italian American Review, an annual three-day, international conference, the webcasts of Italics 2.0 and Nota Bene, and the upcoming exhibition “Migrating Towers: The Gigli of Nola and Beyond.” We have been able to do this and much more, providing it all free to you, the Calandra Institute's friends and colleagues. Tickets: $35 at the door or in advance. Cash or check made payable to "Friends of the Calandra Institute Foundation." (We do not accept credit cards.) If you are unable to attend the concert, the Calandra Institute is also accepting tax-deductible donations. -

Loud and Colorful, with Total Recall the Performance Artist Penny Arcade, Now an Actress

Loud and Colorful, With Total Recall The Performance Artist Penny Arcade, Now an Actress Ruth Fremson/The New York Times Penny Arcade in her apartment on the Lower East Side. By TIM MURPHY Published: October 31, 2013 In 1967, the same year that the playwright Tennessee Williams found himself in the depths of substance abuse, depression and critical failure, a short, busty, outspoken 17- year-old named Susana Ventura completed her tenure in reform school and ran away from working-class New Britain, Conn. She moved to downtown Manhattan, was sheltered by drag queens and fell under the tutelage of gay artists including Andy Warhol; the filmmaker and performance artist Jack Smith; and John Vaccaro, founder of the avant-garde Play-House of the Ridiculous theater group. Enlarge This Image Ruth Fremson/The New York Times Penny Arcade, left, with Mink Stole, rehearsing the Tennessee Williams one-act,“The Mutilated.” Enlarge This Image Leee Black Childers From left, Patti Smith, Jackie Curtis and Penny Arcade in 1969. Williams endured several more years of personal and professional anguish before he died at 71 in 1983. Ms. Ventura, taking a note from her drag mentors, quickly renamed herself Penny Arcade and by the 1990s had become a prominent performance artist downtown, presenting shows that, souped up by a troupe of burlesque dancers, mixed her vivid personal biography with passionate and sarcastic monologues about the AIDS epidemic, the women’s and gay rights movements, and, above all else, her own right to flaunt her body and her mind. Williams and Penny Arcade, now 63, never met, but she says they are kindred spirits, which makes her excited to deliver the coarse poetry of his late work onstage. -

Planet Talk: LES Cultural Icon Penny Arcade | Senior Planet

Planet Talk: LES Cultural Icon Penny Arcade | Senior Planet http://seniorplanet.org/planet-talk-les-cultural-icon-penny-arcade/ Planet Talk: LES Cultural Icon PRINT THIS Penny Arcade Steve Ellman , 02/12/2013 0 Comments Penny Arcade came by her legendary status the 60s way. Born Susana Ventura, in her teens she ran away from a working class Connecticut home and took shelter among the inspired deviants of the Lower East Side. She hung out and performed with experimental geniuses like Jack Smith and Charles Ludlam (Theatre of The Ridiculous), and with Andy Warhol at his Factory. Later, she turned to writing and performing provocative, streetwise, often hilarious works of her own, most famously the Jesse Helms-era sex-and-censorship show “Bitch! Dyke! Faghag! Whore!” Since 1999, along with filmmaker Steve Zehenter, Penny has co-produced the video-based oral-history documentary project and archive The Lower Eastside Biography Project: Stemming The Tide of Cultural Amnesia. The project shepherds young videographers through a process of creating a biography of a LES luminary – among those completed are Judith Malina, Richard Foreman, and Quintin Crisp. Biographies screen weekly on Time Warner Channel and stream live on Manhattan 1 of 4 1/16/2014 11:41 AM Planet Talk: LES Cultural Icon Penny Arcade | Senior Planet http://seniorplanet.org/planet-talk-les-cultural-icon-penny-arcade/ Neighborhood Network (details below). February 13 at 6:30pm, Penny Arcade and Steve Zehenter will present and discuss clips from some of the project’s biographies. See Calendar for more info . We spoke to Penny by phone on a recent Saturday morning, not long after she had wrapped up a 46-performance London run of her show “Bitch!Dyke!Faghag!Whore!” You’ve always been an outsize and unorthodox person. -

View Program for Arts for Living

ARTS FOR LIVING: ARTISTS FEED THE L.E.S. HOSTED BY ARTS FOR LIVING Arts For Living: Artists Feed the L.E.S. PENNY ARCADE NOMINATION COMMITTEE LAUREN BOYLE is a virtual fundraiser featuring video PARTICIPATING ARTISTS DAVID GARZA commissions by collaborative teams of LINDA DIAZ MEI LUM TRIPPJONES CANAL RESEARCH Lower East Side residents and New York City ELROY GAY ASSOCIATION based filmmakers. Marking 1 year since EUGENE PUGLIA JULIE ATLAS MUZ New York City went into lockdown due to BARBARA KING & ADAM ZHU SANDRA E. WALKER COVID-19, each work is a deeply personal ANNIE TAN BROADCAST PRODUCED BY reflection on the Lower East Side here and GRANITE LIVE PARTICIPATING FILMMAKERS now. A R PRODUCTION MANAGER ALEJANDRO HIDALGO VIOLET TAFARI This screening will be hosted live by Penny Arcade from ALICIA MERSY our historic Playhouse Theater, which for the past year ALON SICHERMAN LIGHTING DESIGNER has been operating as our Food Access Initiative, a food GOGY ESPARZA NATALIE AVERY pantry that serves 700 Lower East Side residents each ANDY K. BOYCE week who face food insecurity worsened by the COVID-19 SOUND DESIGNER pandemic. FOOD ACCESS INITIATIVE TEAM JAMES KOGAN JON HARPER TYLER DIAZ DECKHAND KAYLYN KILKUSKIE CHRISTINA TANG KIA ROGERS JANET CLANCY PRODUCTION ASSISTANT LUKE VAN MEVEREN OLIVIA CRAWFORD MIKE TAYLOR JOHN-PHILIP FAIENZA SPECIAL THANKS JUSTIN FAIRCLOTH CHRISTIE BOWERS RANDY LUNA RICHARD DELIGTER MILLIE KAPP LIANNE DIFABBIO KATIE VOGEL CHELSEA JUPIN CARLOS MONTANEZ & BARBARA KANCELBAUM THE COMMUNITY COVID KUMASI SADIKI & RESPONSE TEAM THE GOOD COMPANY LILAH MEJIA & THE MOBILE ELLEN SCHNEIDERMAN MARKET TEAM DEANNA SORGE KATIE VOGEL ABRONS ARTS CENTER ARTS FOR LIVING: ARTISTS FEED THE L.E.S.