Building Australia's Energy Literacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Regional Boundaries and Marginal Loss Factors for the 2012-13 Financial Year

LIST OF REGIONAL BOUNDARIES AND MARGINAL LOSS FACTORS FOR THE 2012-13 FINANCIAL YEAR PREPARED BY: Systems Capability VERSION: 1.4 DATE: 12/06/2012 FINAL LIST OF REGIONAL BOUNDARIES AND MARGINAL LOSS FACTORS FOR THE 2012-13 FINANCIAL YEAR Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 7 2 MLF calculation ................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Rules requirements .................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Inter-regional loss factor equations ............................................................................. 8 2.3 Intra-regional loss factors ........................................................................................... 8 2.4 Forward-looking Loss Factors .................................................................................... 8 3 Application of the forward-looking loss factor methodology for 2012/13 financial year .................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Overview of the Forward-looking Loss Factor Methodology ....................................... 8 3.2 Data requirements ...................................................................................................... 9 3.3 Connection point definitions ..................................................................................... 10 3.4 Connection point load data ...................................................................................... -

Alinta Energy Sustainability Report 2018/19

Alinta Energy Sustainability Report 2018/19 ABN 39 149 229 998 Contents A message from our Managing Director and CEO 2 Employment 50 FY19 highlights 4 Employment at Alinta Energy 52 Key sustainability performance measures 6 Employee engagement 53 Employee data 54 Our business 8 Supporting our people 55 Offices 10 Ownership 10 Our communities 60 Where we operate 12 Community development program 62 Electricity generation portfolio 14 Employee volunteering 62 Sales and customers 17 Sponsorships, donations and partnerships 64 Vision and values 18 Excellence Awards – community contribution 64 Business structure and governance 19 Community impacts from operations 65 Executive leadership team 20 Management committees 21 Markets and customers 66 Board biographies 21 Customer service 68 Risk management and compliance 23 Branding 72 Economic health 24 New products and projects 74 Market regulation and compliance 74 Safety 26 Fusion – our transformation program 77 Safety performance 28 Safety governance 29 Our report 80 Safety and wellbeing initiatives and programs 32 Reporting principles 82 Glossary 83 Environment 34 GRI and UNSDG content index 85 Climate change and energy industry 36 Sustainability materiality assessment 88 National government programs, policies and targets 39 Deloitte Assurance Report 96 State government programs, policies and targets 40 Energy consumption and emissions 42 Our approach to renewable energy 43 Energy efficiency and emission reduction projects 45 Environmental compliance 46 Waste and water 47 Case study 48 2018/19 Alinta Energy - Sustainability Report Page 1 Changes to our vision and leadership A message My comment above on our new vision to be the best energy company sounds a little different than in the past. -

PROSPECTUS for the Offer of 57,142,858 Shares at $1.75 Per Share in ERM Power

PROSPECTUS for the offer of 57,142,858 Shares at $1.75 per Share in ERM Power Global Co-ordinator Joint Lead Managers ERMERR M POWERPOWEPOWP OWE R PROSPECTUSPROSPEOSP CTUCTUSTU 1 Important Information Offer Information. Proportionate consolidation is not consistent with Australian The Offer contained in this Prospectus is an invitation to acquire fully Accounting Standards as set out in Sections 1.2 and 8.2. paid ordinary shares in ERM Power Limited (‘ERM Power’ or the All fi nancial amounts contained in this Prospectus are expressed in ‘Company’) (‘Shares’). Australian currency unless otherwise stated. Any discrepancies between Lodgement and listing totals and sums and components in tables and fi gures contained in this This Prospectus is dated 17 November 2010 and a copy was lodged with Prospectus are due to rounding. ASIC on that date. No Shares will be issued on the basis of this Prospectus Disclaimer after the date that is 13 months after 17 November 2010. No person is authorised to give any information or to make any ERM Power will, within seven days after the date of this Prospectus, apply representation in connection with the Offer which is not contained in this to ASX for admission to the offi cial list of ASX and quotation of Shares on Prospectus. Any information not so contained may not be relied upon ASX. Neither ASIC nor ASX takes any responsibility for the contents of this as having been authorised by ERM Power, the Joint Lead Managers or Prospectus or the merits of the investment to which this Prospectus relates. -

Surat Basin Non-Resident Population Projections, 2021 to 2025

Queensland Government Statistician’s Office Surat Basin non–resident population projections, 2021 to 2025 Introduction The resource sector in regional Queensland utilises fly-in/fly-out Figure 1 Surat Basin region and drive-in/drive-out (FIFO/DIDO) workers as a source of labour supply. These non-resident workers live in the regions only while on-shift (refer to Notes, page 9). The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) official population estimates and the Queensland Government’s population projections for these areas only include residents. To support planning for population change, the Queensland Government Statistician’s Office (QGSO) publishes annual non–resident population estimates and projections for selected resource regions. This report provides a range of non–resident population projections for local government areas (LGAs) in the Surat Basin region (Figure 1), from 2021 to 2025. The projection series represent the projected non-resident populations associated with existing resource operations and future projects in the region. Projects are categorised according to their standing in the approvals pipeline, including stages of In this publication, the Surat Basin region is defined as the environmental impact statement (EIS) process, and the local government areas (LGAs) of Maranoa (R), progress towards achieving financial close. Series A is based Western Downs (R) and Toowoomba (R). on existing operations, projects under construction and approved projects that have reached financial close. Series B, C and D projections are based on projects that are at earlier stages of the approvals process. Projections in this report are derived from surveys conducted by QGSO and other sources. Data tables to supplement the report are available on the QGSO website (www.qgso.qld.gov.au). -

ERM Power's Neerabup

PROSPECTUS for the offer of 57,142,858 Shares at $1.75 per Share in ERM Power For personal use only Global Co-ordinator Joint Lead Managers ERMERR M POWERPOWEPOWP OWE R PROSPECTUSPROSPEOSP CTUCTUSTU 1 Important Information Offer Information. Proportionate consolidation is not consistent with Australian The Offer contained in this Prospectus is an invitation to acquire fully Accounting Standards as set out in Sections 1.2 and 8.2. paid ordinary shares in ERM Power Limited (‘ERM Power’ or the All fi nancial amounts contained in this Prospectus are expressed in ‘Company’) (‘Shares’). Australian currency unless otherwise stated. Any discrepancies between Lodgement and listing totals and sums and components in tables and fi gures contained in this This Prospectus is dated 17 November 2010 and a copy was lodged with Prospectus are due to rounding. ASIC on that date. No Shares will be issued on the basis of this Prospectus Disclaimer after the date that is 13 months after 17 November 2010. No person is authorised to give any information or to make any ERM Power will, within seven days after the date of this Prospectus, apply representation in connection with the Offer which is not contained in this to ASX for admission to the offi cial list of ASX and quotation of Shares on Prospectus. Any information not so contained may not be relied upon ASX. Neither ASIC nor ASX takes any responsibility for the contents of this as having been authorised by ERM Power, the Joint Lead Managers or Prospectus or the merits of the investment to which this Prospectus relates. -

Adapt Depend Sustain

adapt sustain depend able Annual Report 2008/09 contents Highlights 2 Profile 4 Financial Overview 8 adaptable Chairman’s Review 10 Chief Executive’s Review 12 Powerlink continually interacts with government, the energy Powerlink and the National Electricity Market 14 sector, customers and the community to develop its network Network Strategy and Operations 20 to meet Queensland’s and Australia’s changing needs. Network Development 28 Environment 38 Community 46 People 52 Corporate Governance 58 Board of Directors 64 Executive Leadership Team 66 sustainable Directors’ Report 70 Powerlink works closely with the community and specialist Financials 75 advisors to manage its operations in ways that are Statistical Summary 128 environmentally and economically sustainable. Index 132 Glossary and Terms of Measurement 134 dependable Front cover: John Burgess, Field Test Engineering Officer Powerlink’s best-practice systems and dedicated workforce Inside front cover: Adam Hammersley, Assistant Construction Manager, and Lloyd Warr, Lead Line Construction Manager, supervise helicopter stringing of the South Pine to ensure its transmission network is amongst the most reliable Sandgate transmission line in Brisbane and cost effective in the world. Powerlink’s 2008/09 highlights Powerlink Queensland is committed to delivering transmission network and mission related services at world-class levels of safety, reliability and cost effectiveness. To be the leading Transmission Network Service Provider vision in Australia, and one of the best in the world. Reasonable returns for our owners. values Value for money services to our customers. deliverable The wellbeing of our employees. Being a good corporate citizen and community recognition of this. Fair, commercial and courteous dealings with our suppliers. -

Maintaining a Reliable Electricity Supply to Southern (South West and South East) Queensland

FINAL REPORT 5 June 2009 Maintaining a reliable electricity supply to Southern (South West and South East) Queensland Disclaimer While care was taken in preparation of the information in this document, and it is provided in good faith, Powerlink accepts no responsibility or liability (including without limitation, liability to any person by reason of negligence or negligent misstatement) for any loss or damage that may be incurred by any person acting in reliance on this information or assumptions drawn from it, except to the extent that liability under any applicable Queensland or Commonwealth of Australia statute cannot be excluded. This document has been prepared for the purpose of inviting information, comment and discussion from interested parties. The document has been prepared using information provided by a number of third parties. It contains assumptions regarding, among other things, economic growth and load forecasts which may or may not prove to be correct. Powerlink makes no representation or warranty as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability for particular purposes, of the information in this document. All information should be independently verified before assessing any investment proposals. DOCUMENT PURPOSE For the benefit of those not familiar with the National Electricity Rules (Rules) and the National Electricity Market (NEM), Powerlink offers the following clarifications on the purpose and intent of this document: 1. The Rules require Powerlink to carry out forward planning to identify future reliability of supply requirements and to issue this type of document for “proposed new large network assets”. 2. The Rules require Powerlink to identify, evaluate and compare both network and non-network options (including generation and demand side management) to determine which can address the future supply requirements at the lowest cost to the market and hence to electricity consumers. -

Barriers to Entry in Electricity Generation

Barriers to entry in electricity generation A report outline for the AEMC Dr Tom Hird Mr Paul Reynolds Mr Daniel Young Ms Johanna Hansson Dr Yuliya Moore June 2012 Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 Definition of barriers to entry 4 Conditions giving rise to barriers to entry 5 Testing for the significance of barriers to entry 5 1. Entry in general and specifically in generation 8 1.1. Entry strategies (and entry deterrence strategies) in general 8 1.2. Entry into electricity generation 11 2. Conceptual framework for analysing barriers to entry 13 2.1. Applying the framework to the NEM 16 2.2. Defining long run marginal cost 18 2.3. Full definition of conditions giving rise to SMP 19 3. Potential barriers to entry in the NEM 20 3.1. Ineffective competition among incumbent firms 20 3.2. What does not constitute a barrier to entry 21 3.3. Barriers to entry arising from inefficient imposts on new entrants 22 3.4. Other structural barriers to entry 22 3.5. Strategic barriers to entry 23 4. Assessing effectiveness of competition among incumbents 24 5. Evidence on barriers to entry in the NEM 36 5.1. The significance of inefficient imposts on new entrants 36 5.2. Other structural barriers to entry 42 5.3. Strategic barriers to entry 43 5.4. Evidence from market outcomes 53 5.5. Overall conclusion 64 Appendix A. Incentives to withhold supply 67 A.1. Commodity market cost curves 67 A.2. Incentives to withhold supply and the concept of the ‘critical slope’ 69 A.3. -

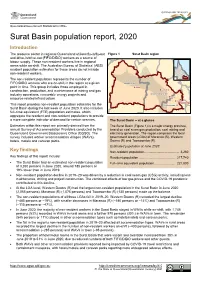

Surat Basin Population Report, 2020

Queensland Government Statistician’s Office Surat Basin population report, 2020 Introduction The resource sector in regional Queensland utilises fly-in/fly-out Figure 1 Surat Basin region and drive-in/drive-out (FIFO/DIDO) workers as a source of labour supply. These non-resident workers live in regional areas while on-shift. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) resident population estimates for these areas do not include non-resident workers. The non-resident population represents the number of FIFO/DIDO workers who are on-shift in the region at a given point in time. This group includes those employed in construction, production, and maintenance at mining and gas industry operations, renewable energy projects and resource-related infrastructure. This report provides non-resident population estimates for the Surat Basin during the last week of June 2020. It also includes full–time equivalent (FTE) population estimates, which aggregate the resident and non-resident populations to provide a more complete indicator of demand for certain services. The Surat Basin – at a glance Estimates within this report are primarily derived from the The Surat Basin (Figure 1) is a major energy province, annual Survey of Accommodation Providers conducted by the based on coal seam gas production, coal mining and Queensland Government Statistician’s Office (QGSO). The electricity generation. The region comprises the local survey includes worker accommodation villages (WAVs), government areas (LGAs) of Maranoa (R), Western hotels, motels and caravan parks. Downs (R) and Toowoomba (R). Estimated population at June 2020: Key findings Non-resident population ....................................... 3,260 Key findings of this report include: Resident population ........................................ -

Surat Basin Population Report, 2019

Queensland Government Statistician’s Office Surat Basin population report, 2019 Introduction The resource sector in regional Queensland utilises fly-in/fly-out Figure 1 Surat Basin region and drive-in/drive-out (FIFO/DIDO) workers as a source of labour supply. These non-resident workers live in regional areas while on-shift. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) resident population estimates for these areas do not include non-resident workers. The non-resident population represents the number of FIFO/DIDO workers who are on-shift in the region at a given point in time. This group includes those employed in construction, production, and maintenance at mining and gas industry operations, renewable energy projects and resource-related infrastructure. This report provides non-resident population estimates for the Surat Basin during the last week of June 2019. It also includes full–time equivalent (FTE) population estimates, which aggregate the resident and non-resident populations to provide a more complete indicator of demand for certain services. The Surat Basin – at a glance Estimates within this report are primarily derived from the The Surat Basin (Figure 1) is a major energy province, annual Survey of Accommodation Providers conducted by the based on coal seam gas production, coal mining and Queensland Government Statistician’s Office (QGSO). The electricity generation. The region comprises the local survey includes worker accommodation villages (WAVs), government areas (LGAs) of Maranoa (R), Western hotels, motels, and caravan parks. Downs (R) and Toowoomba (R). Population at June 2019: Key findings Non-resident population ....................................... 4,040 Key findings of this report include: Resident population ........................................ -

Darling Downs Solar Farm Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 - Referral

Origin Energy Darling Downs Solar Farm Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 - Referral 27 April 2016 Referral of proposed action Project title: Darling Downs Solar Farm 1 Summary of proposed action 1.1 Short description Origin Energy (the proponent) is seeking to develop a Solar Photovoltaic Generation Facility (solar farm) on Lot 119 SP227731, with ancillary power connections planned on Lot 121 SP178856, Grahams Road at Kogan in Queensland (the proposed action). Figure 1 shows the location of the proposed action. The development will consist of a number of panel areas, comprising arrays of solar panels connected to associated inverter stations (up to 200), which convert the low voltage DC current from approximately 1-2 ha of solar panels up to 33 Kilovolt (kV) medium voltage AC current. A high voltage internal electricity network will be used to collect the power from the inverter stations to the site’s substation. The internal network will be up to 33 kV and will consist of both underground and above ground cabling. At the substation the 33 kV input power will be converted to a suitable voltage for connection to the National Electricity Grid via an existing connection point at the Darling Downs Power Station. The potential development area (refer Figure 1) will contain all of the infrastructure for the solar farm including: Æ photovoltaic solar panels Æ internal access roads and tracks Æ high voltage substation Æ underground high voltage transmission lines Æ overhead high voltage transmission lines Æ administration building Æ maintenance and storage shed Æ vehicle car park Æ main gate crossover widening Æ pilot specific inclusions Æ miscellaneous infrastructure. -

GLNG Gas Transmission Pipeline

GLNG Gas Transmission Pipeline Significant Species Management Plan for KP0 to KP30, KP30 to KP40, KP40 to KP130, KP130 to KP312, KP312 to KP408.81, KP408.81 to KP409.04 and KP413.57 to KP419.69 Part 1 - Overview Document Number: 3380-GLNG-4-1.3-0104 DATE REV REASON FOR ISSUE AUTHOR ENDORSED APPROVED 16.10.15 V Final (issued to DotE) LL MB DR 10/03/17 W Draft for DoEE – approved MB ED ED This document contains confidential information and in not to be disclosed to any third parties without prior written permission from the CEO GLNG Operation PTY Ltd. Page i Contents Abbreviations viii Part 1 – Overview 1-1 1 Introduction 1-1 1.1 Background and purpose 1-1 1.2 Structure of SSMP 1-6 1.3 Definitions 1-6 1.4 Limitations 1-10 2 Project description 1-10 2.1 Overview 1-10 2.2 Construction methodology 1-11 3 Sources of information 1-13 3.1 Pre-clearance surveys 1-13 3.2 Mainland Environmental Management Plan (Mainland EMP) 1-23 3.3 Marine Crossing Environmental Management Plan (MEMP) 1-23 3.4 Curtis Island Environmental Management Plan (Curtis Island EMP) 1-23 3.5 Aquatic Values Management Plan (AVMP) 1-23 3.6 Standards and guidelines 1-24 4 Fauna habitat assessment 1-25 4.1 Core habitat 1-26 4.2 Essential habitat 1-26 4.3 General habitat 1-26 4.4 Unlikely habitat 1-26 5 Significant Species Management Plans 1-26 6 Offsets 1-28 6.1 Background 1-28 6.2 Offset requirements 1-28 6.3 Offset Plan 1-37 7 Common SSMP Procedures 1-38 7.1 Spotter catcher requirements 1-38 7.2 Monitoring, reporting and record keeping 1-38 7.3 Species of Conservation Interest