Two Projects in Onomastic Lexicography 1 Researching The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaelic Names of Plants

[DA 1] <eng> GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS [DA 2] “I study to bring forth some acceptable work: not striving to shew any rare invention that passeth a man’s capacity, but to utter and receive matter of some moment known and talked of long ago, yet over long hath been buried, and, as it seemed, lain dead, for any fruit it hath shewed in the memory of man.”—Churchward, 1588. [DA 3] GAELIC NAMES OE PLANTS (SCOTTISH AND IRISH) COLLECTED AND ARRANGED IN SCIENTIFIC ORDER, WITH NOTES ON THEIR ETYMOLOGY, THEIR USES, PLANT SUPERSTITIONS, ETC., AMONG THE CELTS, WITH COPIOUS GAELIC, ENGLISH, AND SCIENTIFIC INDICES BY JOHN CAMERON SUNDERLAND “WHAT’S IN A NAME? THAT WHICH WE CALL A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME WOULD SMELL AS SWEET.” —Shakespeare. WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXXXIII All Rights reserved [DA 4] [Blank] [DA 5] TO J. BUCHANAN WHITE, M.D., F.L.S. WHOSE LIFE HAS BEEN DEVOTED TO NATURAL SCIENCE, AT WHOSE SUGGESTION THIS COLLECTION OF GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS WAS UNDERTAKEN, This Work IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. [DA 6] [Blank] [DA 7] PREFACE. THE Gaelic Names of Plants, reprinted from a series of articles in the ‘Scottish Naturalist,’ which have appeared during the last four years, are published at the request of many who wish to have them in a more convenient form. There might, perhaps, be grounds for hesitation in obtruding on the public a work of this description, which can only be of use to comparatively few; but the fact that no book exists containing a complete catalogue of Gaelic names of plants is at least some excuse for their publication in this separate form. -

“If Music Be the Food of Love, Play On

What’s in a Name? As Shakespeare had Juliet say, “That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Maybe so, but in New Orleans there’s more to a name than meets the ear. The Crescent City is home to many sweet-sounding names, especially those of its ladies. What could be more beautiful names than those of Voudou practitioner Marie Laveau or sarong siren Dorothy Lamour? Actually Dorothy was born Mary Leta Dorothy Slaton, but her parents’ marriage lasted only a few years. Her mother re-married a man named Clarence Lambour, and Dorothy took his last name. Lambour became Lamour, a much better choice in that it oozes love (toujours l’amour). She took it along with her on all those “Road” pictures with Bob Hope and Bing Crosby. Dorothy Lamour (1914 – 1996), New Orleans’ own siren in a sarong Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame after having recorded over 60 singles for the Imperial label, placing 40 songs in the R&B top 10 charts and 11 top 10 singles on the pop charts, Antoine Dominique “Fats” Domino, Jr. is a New Orleans musical legend with a Creole name to match. It flows from the lips mellifluously like a beignet washed down with café au lait. A sure sign that a name has star potential is the fact that someone has tried, in some way, to usurp its power. In the case of “Fats”, American Bandstand host Dick Clark’s wife Barbara took the name, changed it around ever so slightly and bestowed a new name to an up-and-coming Rock and Roll personality. -

Human-Machine Communication

Volume 2, 2021 ISSN 2638-602X (print)/ISSN 2638-6038 (online) Human-Machine Communication ISSN 2638-602X (print)/ISSN 2638-6038 (online) Copyright © 2021 Human-Machine Communication www.hmcjournal.com Human-Machine Communication (HMC) is an annual peer-reviewed, open access publication of the Communication and Social Robotics Labs (combotlabs.org), published with support from the Nicholson School of Communication and Media at the University of Central Florida. Human- Machine Communication (Print: ISSN 2638-602X) is published in the spring of each year (Online: ISSN 2638-6038). Institutional, organizational, and individual subscribers are invited to purchase the print edition using the following mailing address: Human-Machine Communication (HMC) Communication and Social Robotics Labs Western Michigan University 1903 W. Michigan Ave. 300 Sprau Tower Kalamazoo, MI 49008 Print Subscriptions: Regular US rates: Individuals: 1 year, $40. Libraries and organizations may subscribe for 1 year, $75. If subscribing outside of the United States, please contact the Editor-in-Chief for current rate. Checks should be made payable to the Communication and Social Robotics Labs. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License . All articles in HMC are open access and can be distributed under the creative commons license. Human-Machine Communication Volume 2, 2021 Volume Editor Leopoldina Fortunati, University of Udine (Italy) Editor-in-Chief Autumn Edwards, Western Michigan University (U.S.A.) Associate Editors Patric R. Spence, University of Central Florida (U.S.A.) Chad Edwards, Western Michigan University (U.S.A.) Editorial Board Somaya Ben Allouch, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences (Netherlands) Maria Bakardjieva, University of Calgary (Canada) Jaime Banks, West Virginia University (U.S.A.) Naomi S. -

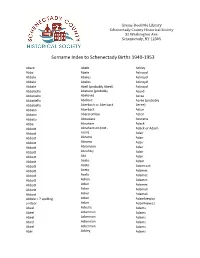

Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953

Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Abare Abele Ackley Abba Abele Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abell (probably Abeel) Ackroyd Abbatiello Abelone (probably Acord Abbatiello Abelove) Acree Abbatiello Abelove Acree (probably Abbatiello Aberbach or Aberback Aeree) Abbato Aberback Acton Abbato Abercrombie Acton Abbato Aboudara Acucena Abbe Abraham Adack Abbott Abrahamson (not - Adack or Adach Abbott nson) Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abramson Adair Abbott Abrofsky Adair Abbott Abt Adair Abbott Aceto Adam Abbott Aceto Adamczak Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Acken Adamec Abbott Acker Adamec Abbott Acker Adamek Abbott Acker Adamek Abbzle = ? spelling Acker Adamkiewicz unclear Acker Adamkiewicz Abeel Ackerle Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abel Ackley Adams Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Adams Adamson Ahl Adams Adanti Ahles Adams Addis Ahman Adams Ademec or Adamec Ahnert Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adriance Ahrens Adams Adsit Aiken Adams Aeree Aiken Adams Aernecke Ailes = ? Adams Agans Ainsworth Adams Agans Aker (or Aeher = ?) Adams Aganz (Agans ?) Akers Adams Agare or Abare = ? Akerson Adams Agat Akin Adams Agat Akins Adams Agen Akins Adams Aggen Akland Adams Aggen Albanese Adams Aggen Alberding Adams Aggen Albert Adams Agnew Albert Adams Agnew Albert or Alberti Adams Agnew Alberti Adams Agostara Alberti Adams Agostara (not Agostra) Alberts Adamski Agree Albig Adamski Ahave ? = totally Albig Adamson unclear Albohm Adamson Ahern Albohm Adamson Ahl Albohm (not Albolm) Adamson Ahl Albrezzi Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. -

1954 Surname

Surname Given Age Date Page Maiden Note Aaby Burt Leonard 55 1-Jun 18 Acevez Maximiliano 54 26-Nov A-4 Adam John 74 21-Sep 4 Adams Agnes 66 22-Oct 40 Adams George 71 7-Sep 8 Adams Maude (Byrd) 69 23-May A-4 Adams Max A. 63 5-May 10 Adams Michael 3 mons 18-Feb 32 Adams Thomas 80 14-Jun 4 Adkins Dr. Thomas D. 64 15-Jan 4 Adley Matthew B. 60 8-Sep 13 Adzima Michael, Sr. 17-Nov A-4 Alexanter Sadie 70 24-Aug 18 Allan Susan Ann 8 mons 28-Nov A-7 Allen Charles M. 75 7-Apr 2 Allen Clara Jane 84 24-May 17 Allen George W. 78 11-Apr 4 Allen Luther S. 59 28-Nov A-7 Altgilbers Pauline M. 43 11-Nov D-4 Ambos Susan 88 3-Jan 4 Amodeo Phillip 65 24-Aug 18 Anderson Andrew 60 5-Mar 31 Anderson Anna Marie 69 7-Jun 17 Anderson Christina 95 16-Nov 4 Anderson Cynthia Rae 1 day 5-Oct 10 Anderson William 58 3-Dec A-11 Anderson William R. (Bob) 58 5-Dec A-4 Andree Ernest W. 80 25-Jan 16 Andrews Josephine 2-Nov 4 Andring Nicholas 66 20-May 28 Antanavic Tekla 68 5-May 10 Arbuckle May 59 22-Jun 4 Arendell Lula 77 4-Jul A-4 Armstrong Margaret 65 14-Jun 4 Arnold Flora L. 8-Oct 4 Arnold Paul Sigwalt 61 18-Jul A-4 Asafaylo Glenn 6 6-Jan 1 Asby Henry 60 24-Oct A-4 Asztalos Moses 58 11-Feb 28 Augustian Weuzel, Sr. -

<I>Comment Vous Appelez-Vous</I>?: Why the French Change Their Names

Comment vous appelez-vous?: Why the French Change Their Names James E. Jacob California State University, Chico and Pierre L. Horn Wright State University We examine the history, processes, and motivations which explain in part why and how the French change their names. Studying a small but representative sample of official name changes mandatorily published in the JournaL OfficieL de La Republique Franfaise at certain moments of post-World War II history (1946, 1963, and 1992-1995), we identify the four most important reasons for changing names: because they are obscene or. pejorative; ridiculous; perceived as too foreign, especially too Arab or too Jewish; or to add the patent of nobility . While we express surprise that names of these kinds still exist in contemporary France, we also recognize that the decision to request a name change at this late date is the last refuge for families who have long suffered indignities and humiliations because of their names. The name I bear is not only a "gift" from my father or my mother; it is an integral part of myself; it has defined me ... since my childhood. Francois eros [T]he name is a family possession; it is the cement of the family. Marianne Mulon Names 46.1 (March 1998):3-28 ISSN:0027-7738 © 1998by The American Name Society 3 4 Names 46.1 (March 1998) With the Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterets in 1539, which, according to Albert Dauzat (1949, 40), codified a long-established custom of assigning and preserving family names, the French monarchy sought to further integrate the diversity of its realm. -

Baylor University Commencement May Seventh and Eighth, Two Thousand Twenty-One

B AYLOR U NIVERSITY C OMMEN C EMENT May Seventh and Eighth, Two Thousand Twenty-one McLane Stadium . Waco, Texas Baylor University Commencement May Seventh and Eighth, Two Thousand Twenty-one Table of Contents 2 Program for Friday Morning The School of Engineering and Computer Science The School of Education The College of Arts & Sciences The Graduate School 3 List of Degrees Presented in Friday Morning Ceremony 8 Program for Friday Afternoon The School of Music The College of Arts & Sciences The Graduate School 9 List of Degrees Presented in Friday Afternoon Ceremony 14 Program for Saturday Morning The Robbins College of Health and Human Sciences The Diana R. Garland School of Social Work The Louise Herrington School of Nursing The Graduate School 15 List of Degrees Presented in Saturday Morning Ceremony 20 Program for Saturday Afternoon The Hankamer School of Business The Graduate School 21 List of Degrees Presented in Saturday Afternoon Ceremony 26 Commencement Traditions A History of Baylor Commencement Academic Regalia The Diploma Graduating with Latin Honors Baylor Interdisciplinary Core Official Baylor Ring Senior Class Gift 28 Faculty Ushers for Commencement Faculty Marshals for Commencement Ceremony Musicians 29 General Information The National Anthem Back Cover “That Good Old Baylor Line” 1 The School of Engineering and Computer Science, The School of Education, The College of Arts & Sciences, and The Graduate School Friday, May 7, 2021, Nine o’clock in the Morning – McLane Stadium Prelude Presentation of Degree Candidates Ceremonial Piece on CWM Rhondda by William Mac Davis President Livingstone The Earle of Oxford’s March by William Byrd, arranged by Assisted by Dr. -

See Who Attended

Company Name First Name Last Name Job Title Country 24Sea Gert De Sitter Owner Belgium 2EN S.A. George Droukas Data analyst Greece 2EN S.A. Yannis Panourgias Managing Director Greece 3E Geert Palmers CEO Belgium 3E Baris Adiloglu Technical Manager Belgium 3E David Schillebeeckx Wind Analyst Belgium 3E Grégoire Leroy Product Manager Wind Resource Modelling Belgium 3E Rogelio Avendaño Reyes Regional Manager Belgium 3E Luc Dewilde Senior Business Developer Belgium 3E Luis Ferreira Wind Consultant Belgium 3E Grégory Ignace Senior Wind Consultant Belgium 3E Romain Willaime Sales Manager Belgium 3E Santiago Estrada Sales Team Manager Belgium 3E Thomas De Vylder Marketing & Communication Manager Belgium 4C Offshore Ltd. Tom Russell Press Coordinator United Kingdom 4C Offshore Ltd. Lauren Anderson United Kingdom 4Cast GmbH & Co. KG Horst Bidiak Senior Product Manager Germany 4Subsea Berit Scharff VP Offshore Wind Norway 8.2 Consulting AG Bruno Allain Président / CEO Germany 8.2 Consulting AG Antoine Ancelin Commercial employee Germany 8.2 Monitoring GmbH Bernd Hoering Managing Director Germany A Word About Wind Zoe Wicker Client Services Manager United Kingdom A Word About Wind Richard Heap Editor-in-Chief United Kingdom AAGES Antonio Esteban Garmendia Director - Business Development Spain ABB Sofia Sauvageot Global Account Executive France ABB Jesús Illana Account Manager Spain ABB Miguel Angel Sanchis Ferri Senior Product Manager Spain ABB Antoni Carrera Group Account Manager Spain ABB Luis andres Arismendi Gomez Segment Marketing Manager Spain -

Common Naming Patterns Being a Brief Guide to Bynames Jn the Major European Languages and Cultures Commonly Encountered in the SCA

Common Naming Patterns Being A Brief Guide to Bynames Jn the Major European Languages And Cultures Commonly Encountered in the SCA Walraven van Nijmegen Introduction to Personal Names Parts of names In the majority of European cultures, personal names contain two basic kinds of name element: given names and surnames. The given name is so called because the family bestowed it upon the child at birth or christening. Given names may be traditional names in the culture, saints, heroes, honored relatives, and so forth. The pool of given names differs from culture to culture. For example, Giovanni is the characteristically Italian form of John ; the name Kasimir is almost uniquely Polish; and use of the name Teresa did not spread outside of Spain until very late in the SCA period. Because given names vary so much by place and period, describing them adequately is beyond the scope of this article. However, many collections of given names are available online at, among other places, the Medieval Names Archive (“MNA”). Surnames are the second major category of name element. Today’s surnames are inherited family names, but for most of the SCA period, surnames were not inherited by chose to describe an individual and distinguish him or her from other individuals with the same given name. Such surnames are called bynames. Byname Origins and Meanings To understand how bynames originated, imagine that you lived in Amsterdam around 1300. You are listening to a friend sharing local gossip about a man named Jan . Now, one out of every ten people living in Amsterdam is named Jan, so how will you know which one your friend means? Is it big Jan who lives at the edge of town? Jan the butcher? Jan, the son of Willem the candlemaker? You need additional information about who Jan is to identify him, and that is what a byname does. -

The Place Names of Fife and Kinross

1 n tllif G i* THE PLACE NAMES OF FIFE AND KINROSS THE PLACE NAMES OF FIFE AND KINROSS BY W. J. N. LIDDALL M.A. EDIN., B.A. LOND. , ADVOCATE EDINBURGH WILLIAM GREEN & SONS 1896 TO M. J. G. MACKAY, M.A., LL.D., Advocate, SHERIFF OF FIFE AND KINROSS, AN ACCOMPLISHED WORKER IN THE FIELD OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH. INTRODUCTION The following work has two objects in view. The first is to enable the general reader to acquire a knowledge of the significance of the names of places around him—names he is daily using. A greater interest is popularly taken in this subject than is apt to be supposed, and excellent proof of this is afforded by the existence of the strange corruptions which place names are wont to assume by reason of the effort on the part of people to give some meaning to words otherwise unintelligible to them. The other object of the book is to place the results of the writer's research at the disposal of students of the same subject, or of those sciences, such as history, to which it may be auxiliary. The indisputable conclusion to which an analysis of Fife—and Kinross for this purpose may be considered a Fife— part of place names conducts is, that the nomen- clature of the county may be described as purely of Goidelic origin, that is to say, as belonging to the Irish branch of the Celtic dialects, and as perfectly free from Brythonic admixture. There are a few names of Teutonic origin, but these are, so to speak, accidental to the topography of Fife. -

Adaptation and Translation Between French and English Arthurian Romance" (Under the Direction of Edward Donald Kennedy)

Varieties in Translation: Adaptation and Translation between French and English Arthurian Romance Euan Drew Griffiths A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Edward Donald Kennedy Madeline Levine E. Jane Burns Joseph Wittig Patrick O'Neill © 2013 Euan Drew Griffiths ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract EUAN DREW GRIFFITHS: "Varieties in Translation: Adaptation and Translation between French and English Arthurian Romance" (Under the direction of Edward Donald Kennedy) The dissertation is a study of the fascinating and variable approaches to translation and adaptation during the Middle Ages. I analyze four anonymous Middle English texts and two tales from Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur that are translations and adaptations of Old French Arthurian romances. Through the comparison of the French and English romances, I demonstrate how English translators employed a variety of techniques including what we might define as close translation and loose adaptation. Malory, in particular, epitomizes the medieval translator. The two tales that receive attention in this project illustrate his use of translation and adaptation. Furthermore, the study is breaking new ground in the field of medieval studies since the work draws on translation theory in conjunction with textual analysis. Translation theory has forged a re-evaluation of translation as a literary medium. Using this growing field of research and scholarship, we can enhance our understanding of translation as it existed during the Middle Ages. -

Children's First Names and Immigration Background in France

Children’s first names and immigration background in France Mahmood Arai, Damien Besancenot, Kim Huynh, Ali Skalli To cite this version: Mahmood Arai, Damien Besancenot, Kim Huynh, Ali Skalli. Children’s first names and immigration background in France. 2009. halshs-00383090 HAL Id: halshs-00383090 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00383090 Preprint submitted on 12 May 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Children’s first names and immigration background in France Mahmood Arai,∗ Damien Besancenot,† Kim Huynh‡and Ali Skalli§ May 11, 2009 Abstract We present evidence indicating that immigrants and especially those from the Maghreb/Middle-East give first names to their children that are differ- ent from those given by the French majority population. When it comes to natives with an immigrant background, these differences are very lit- tle pronounced. Being born and raised up in France as well as being exposed to the French society and culture through residence, citizenship and the educational system draws individuals with or without immigrant background into similar ways of expressing belongings when choosing first names for their children, indicating the very strong assimilating forces in the French society.