When the Party Closed Down

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EUU Alm.Del Offentligt Referat Offentligt

Europaudvalget 2011-12 EUU Alm.del Offentligt referat Offentligt Europaudvalget REFERAT AF 30. EUROPAUDVALGSMØDE Dato: Torsdag den 3. maj 2012 Tidspunkt: Kl. 10.30 Sted: Vær. 2-133 Til stede: Jens Joel (S), Rasmus Helveg Petersen (RV), Nikolaj Villumsen (EL), Finn Sørensen (EL), Lykke Friis (V), Jakob Ellemann-Jensen (V), Pia Adelsteen (DF) fungerende formand, Merete Riisager (LA), Lene Espersen (KF) Desuden deltog: Børne- og undervisningsminister Christine Antorini, ud- viklingsminister Christian Friis Bach, europaminister Nico- lai Wammen og kulturminister Uffe Elbæk Pia Adelsteen ledede mødet FO Punkt 1. Rådsmøde nr. 3164 (uddannelse, ungdom, kultur og sport – uddannelses- og ungdomsdelen) den 10.-11. maj 2012 Under dette punkt på Europaudvalgets dagsorden forelagde børne- og under- visningsministeren punkt 1-4 på dagsordenen for rådsmødet. De øvrige punk- ter på rådsmødet blev forelagt af kulturministeren under punkt 4 på Euro- paudvalgets dagsorden. Undervisningsministeren: Det er jo ikke så tit, jeg har fornøjelsen af at komme her i Europaudvalget. Det er dejligt, at det sker som led i det danske formand- skab. Jeg vil i dag forelægge punkterne på rådsmødet for uddannelse og ungdom, der finder sted på næste fredag, den 11. maj 2012. Jeg forelægger én sag til forhandlingsoplæg. Det er det første punkt om Erasmus for Alle. De to øvrige sager forelægger jeg til orientering. Uddannelse FO 1. Europa-Parlamentets og Rådets forordning om oprettelse af Erasmus for Alle – EU-programmet for uddannelse, ungdom og idræt – Delvis generel indstilling KOM (2011) 0788 Rådsmøde 3164 – bilag 1 (samlenotat side 2) KOM (2011) 0788 – bilag 2 (grundnotat af 25/1-2012) 1093 30. Europaudvalgsmøde 3/5-12 Undervisningsministeren: Kommissionen fremsatte i november sidste år for- slag til et integreret EU-program for uddannelse, ungdom og idræt. -

74. Møde Ken Denne Eller Næste Valgperiode, Hvordan Har Man Så Tænkt Sig at Onsdag Den 14

Onsdag den 14. april 2010 (D) 1 6) Til beskæftigelsesministeren af: Simon Emil Ammitzbøll (LA): Når regeringen ikke vil være med til at afskaffe efterlønnen i hver- 74. møde ken denne eller næste valgperiode, hvordan har man så tænkt sig at Onsdag den 14. april 2010 kl. 13.00 løse den demografiske og økonomiske udfordring? (Spm. nr. S 1806). Dagsorden 7) Til beskæftigelsesministeren af: Simon Emil Ammitzbøll (LA): 1) Spørgsmål til ministrene til umiddelbar besvarelse (spørgeti- Mener ministeren, at det er mere værdigt at være på efterløn end på me). førtidspension? (Spm. nr. S 1807). 2) Besvarelse af oversendte spørgsmål til ministrene (spørgetid). (Se nedenfor). 8) Til beskæftigelsesministeren af: Bjarne Laustsen (S): Hvordan vil ministeren sikre, at f.eks. en hustru, der har arbejdet i sin ægtefælles virksomhed, men er blevet opsagt og reelt fratrådt, 1) Til indenrigs- og sundhedsministeren af: som står til rådighed, er aktivt jobsøgende og har betalt sit kontin- Liselott Blixt (DF): gent, kan få understøttelse? Hvordan stiller ministeren sig til forslaget fra Kræftens Bekæmpelse, (Spm. nr. S 1822). der har foreslået, at det fremover skal være patienten selv og ikke den behandlende læge, der indstiller til second opinion? 9) Til beskæftigelsesministeren af: (Spm. nr. S 1820). Bjarne Laustsen (S): Hvorfor sikrer ministeren ikke, at jobcentrene stiller samme krav til, 2) Til indenrigs- og sundhedsministeren af: når de langt om længe har bevilget arbejdsløse en voksenlærlingeud- Liselott Blixt (DF): dannelse, for så vidt angår krav om jobsøgning, rådighed og betaling Hvad er ministerens holdning til, at Region Sjælland er en betragte- i skolepraktikperioden? lig mere »usund« region end de andre regioner, og bør der iværksæt- (Spm. -

EUI RSCAS Working Paper 2020

RSCAS 2020/88 Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Integrating Diversity in the European Union (InDivEU) The Politics of Differentiated Integration: What do Governments Want? Country Report - Denmark Viktor Emil Sand Madsen European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Integrating Diversity in the European Union (InDivEU) The Politics of Differentiated Integration: What do Governments Want? Country Report - Denmark Viktor Emil Sand Madsen EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2020/88 Terms of access and reuse for this work are governed by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC- BY 4.0) International license. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper series and number, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © Viktor Emil Sand Madsen, 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY 4.0) International license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Published in December 2020 by the European University Institute. Badia Fiesolana, via dei Roccettini 9 I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual author(s) and not those of the European University Institute. This publication is available in Open Access in Cadmus, the EUI Research Repository: https://cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, created in 1992 and currently directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. -

Det Offentlige Danmark 2018 © Digitaliseringsstyrelsen, 2018

Det offentlige Danmark 2018 © Digitaliseringsstyrelsen, 2018 Udgiver: Finansministeriet Redaktion: Digitaliseringsstyrelsen Opsætning og layout: Rosendahls a/s ISBN 978-87-93073-23-4 ISSN 2446-4589 Det offentlige Danmark 2018 Oversigt over indretningen af den offentlige sektor Om publikationen Den første statshåndbog i Danmark udkom på tysk i Oversigt over de enkelte regeringer siden 1848 1734. Fra 1801 udkom en dansk udgave med vekslende Frem til seneste grundlovsændring i 1953 er udelukkende udgivere. Fra 1918 til 1926 blev den udgivet af Kabinets- regeringscheferne nævnt. Fra 1953 er alle ministre nævnt sekretariatet og Indenrigsministeriet og derefter af Kabi- med partibetegnelser. netssekretariatet og Statsministeriet. Udgivelsen Hof & Stat udkom sidste gang i 2013 i fuld version. Det er siden besluttet, at der etableres en oversigt over indretningen Person- og realregister af den offentlige sektor ved nærværende publikation, Der er ikke udarbejdet et person- og realregister til som udkom første gang i 2017. Det offentlige Danmark denne publikation. Ønsker man at fremfnde en bestem indeholder således en opgørelse over centrale instituti- person eller institution, henvises der til søgefunktionen oner i den offentlige sektor i Danmark, samt hvem der (Ctrl + f). leder disse. Hofdelen af den tidligere Hof- og Statskalen- der varetages af Kabinetssekretariatet, som stiller infor- mationer om Kongehuset til rådighed på Kongehusets Redaktionen hjemmeside. Indholdet til publikationen er indsamlet i første halvår 2018. Myndighederne er blevet -

Day by Day Summary of the Election Campaign

Day by Day Summary of the Election Campaign Friday, 26 August It was Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen’s plan to introduce a bonus to people purchasing a house. This bonus has been criticized for artificially inflating house prices and therefore for being a bad way to instigate growth. On Saturday 20 August the Social Democrats (S) somehow learned about the plan and decided to launch it themselves, despite Helle Thorning-Schmidt having said on Friday that she did not want to introduce measures to stimulate the housing market. This led to a chaotic Saturday where Løkke Rasmussen and the Liberal Party (V) tried to do damage control. Quickly the Danish People’s Party (DF) declared their opposition to the plan due to a lot of their voters not being house owners. Liberal Alliance (LA) is as a general rule opposed to state subsidies so they were opposed as well leaving V and the Conservative Party (K) alone with the plan on the blue wing. On the red wing the situation was similar. S and the Socialist People’s Party (SF) agreed on the idea while the Unity List (EL) represents the left wing and therefore does not believe in the state funding those with the means to buy a house – plus a lot of their voters rent their homes. The Social Liberal Party (R) is opposed with the argument that the plan is a shortsighted one which will probably not do much for the economy anyway. Thus S-SF and VK were alone and they did not want to cooperate to get a majority for the plan. -

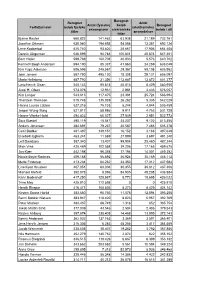

Se Samlet Liste Over Modtagere I 2020

Beregnet Beregnet Antal Antal (fysiske) beløb Beregnet Forfatternavn beløb fysiske (elektroniske) eksemplarer elekroniske beløb i alt titler anvendelser titler Bjarne Reuter 668.822 141.462 63.938 21.189 732.761 Josefine Ottesen 638.040 194.693 54.084 13.381 692.124 Lene Kaaberbøl 625.740 93.802 28.667 17.906 654.408 Dennis Jürgensen 546.599 94.784 100.801 20.674 647.401 Bent Haller 599.769 160.708 40.933 5.576 640.702 Kenneth Bøgh Andersen 594.190 85.337 41.860 24.259 636.049 Kim Fupz Aakeson 606.596 246.567 29.367 58.108 635.962 Jørn Jensen 587.790 495.130 18.308 29.131 606.097 Maria Helleberg 487.790 31.356 113.487 13.872 601.277 Lars-Henrik Olsen 540.143 95.818 40.813 8.429 580.956 Jussi H. Olsen 573.076 12.931 2.981 3.433 576.057 Kim Langer 543.613 117.475 23.381 25.724 566.994 Thorstein Thomsen 515.748 135.939 26.282 5.335 542.029 Hanna Louisa Lützen 527.216 75.133 8.244 4.844 535.459 Jesper Wung-Sung 521.817 58.986 9.911 4.753 531.728 Hanne-Vibeke Holst 494.823 60.027 27.949 2.951 522.773 Sara Blædel 490.119 15.047 23.237 9.122 513.356 Anders Johansen 484.691 79.237 20.587 7.465 505.278 Cecil Bødker 481.497 139.151 16.152 3.188 497.649 Elsebeth Egholm 463.241 11.869 27.999 3.697 491.240 Leif Davidsen 387.340 13.407 99.904 20.460 487.244 Mich Vraa 420.469 102.558 39.206 17.165 459.675 Jan Kjær 442.198 96.358 17.194 14.001 459.392 Nicole Boyle Rødtnes 409.188 56.692 36.924 35.169 446.112 Mette Finderup 413.234 64.262 24.350 17.312 437.584 Line Kyed Knudsen 407.051 68.304 30.355 36.812 437.406 Michael Krefeld 352.078 8.096 84.905 -

EUU Alm.Del Offentligt Referat Offentligt

Europaudvalget 2009-10 EUU Alm.del Offentligt referat Offentligt Europaudvalget REFERAT AF 36. EUROPAUDVALGSMØDE Dato: Fredag den 28. maj 2010 Tidspunkt: Kl. 10.20 Sted: Vær. 2-133 Til stede: Anne-Marie Meldgaard (S) formand, Flemming Møller (V), Pia Adelsteen (DF), Kim Mortensen (S), Yildiz Akdogan (S), Anne Grete Holmsgaard (SF), Pia Olsen Dyhr (SF), Lone Dybkjær (RV), Per Clausen (EL) Desuden deltog: Justitsminister Lars Barfoed, integrationsminister Birthe Rønn Hornbech, klima- og energiminister Lykke Friis, for- svarsminister Gitte Lillelund Bech, fødevareminister Hen- rik Høegh og videnskabsminister Charlotte Sahl-Madsen FO Punkt 1. Rådsmøde nr. 3018 (retlige og indre anliggender) den 3.-4. juni 2010 Dagsordenspunkterne 1a, 2-12 og 14-15 henhører under Justitsministeriets ressort. Punkt 13 er delt ressort mellem Justitsministeriet og Udenrigsministeriet. Punkt 16 henhører under Økonomi- og Erhvervsministeriet. Punkt 17 henhører under Forsvarsministeriets ressort. Punkterne 1b, 18-27 og 29 hører under Integrationsministeriets ressort. Punkterne 1b, 18-27 og 29 blev forelagt af integrationsministeren, før justits- ministeren forelagde sine punkter. Punkterne 1a og 2-16 blev derefter forelagt af justitsministeren. Punkt 17 blev forelagt af forsvarsministeren under punkt 3 på Europaudval- gets dagsorden. På grund af afstemninger i salen kom mødet i Europaudvalget først i gang kl. 10.20, og man tog først integrationsministerens og derefter justitsministerens punkter, idet justitsministeren ikke var clearet. Formanden oplyste, at man fra lovsekretariatet havde fået at vide, at afstem- ningerne formentlig ville være afsluttet inden kl. 10. Integrationsministeren: Jeg forelægger dagsordenspunkt 1b og punkterne 18-27, der alle er til orientering. Jeg har også under dagsordenens punkt 29 en kort melding om en retssag, der er under opsejling i EU. -

Kabinettsumbildung Dänemark

LÄNDERBERICHT Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. DÄNEMARK CATJA C. GAEBEL 22. Februar 2010 Kabinettsumbildung in Dänemark www.kas.de NEUE ZEITEN FÜR RASMUSSENS KABINETT www.kas.de/london Sieben neue Minister übernehmen heute Larsen Kommentator der Zeitung zum ersten Mal ein Ministerium und acht Berlingske Tidende. Kabinettsmitglieder wechseln ihre Ressorts. Der dänische Premierminister Die neue Verteidigungsministerin Lars Løkke Rasmussen kann mit dieser Kabinettsumbildung das geerbte Kabinett Gitte Lillelund Bech (Liberal) wird die seines Vorgängers, des NATO erste Frau sein, die das Amt des Generalsekretärs Anders Fogh Verteidigungsministers besetzt. Damit Rasmussen, zur Seite legen und kann wird sie ein schweres Erbe in einem somit sein eigenes Kabinett vorzeigen. Es Ministerium übernehmen, welches bislang soll neue Zeiten widerspiegeln. von einem beliebten, aber führungsschwachen Minister besetzt Neue Zeiten geleitet wurde. Ihre Aufgabe wird es sein, das Ministerium wieder ins Gleichgewicht Der Winter in Dänemark ist dieses Jahr zu bringen. kalt, sehr kalt. So viel Frost und Schnee gab es seit dem Winter 1962-63 nicht. Der Kampf mit den Regionen, das Budget Frostig war auch seit einiger Zeit die und die Überbezahlung privater Stimmung im Kabinett von Krankenhäuser, sowie ein unkoordinierter Ministerpräsident Lars Løkke Rasmussen. Notdienst waren seit langem Themen, die Daher kam es nicht überraschend, dass als kranker Teil am Premierminister Rasmussen die Analogie Gesundheitsministerium klebten – und des eisigen Winters bei der Präsentation für die nun Gesundheitsminister Jacob seines neuen Kabinetts benutzt. Mit Axel Nielsen (K) trägt und die Regierung seinem neuen „Team“ möchte verlässt. Sein Nachfolger ist Bertel Rasmussen „neue Zeiten“ einläuten und Haarder (Liberal), ehemaliger das „Klima wieder auftauen“, um die Bildungsminister und Veteran in der Finanzlage und das Wachstum wieder bürgerlichen Regierung. -

Ecfr.Eu We Are Living Through a Global Counter-Revolution

ecfr.eu We are living through a global counter-revolution. The institutions and values of liberal internationalism are being eroded beneath our feet and societies are becoming increasingly polarised. The consensus for EU action is increasingly difficult to forge, but there is a way forward. In this new world, the European Council on Foreign Relations will take a bottom-up approach to building grassroots consensus for greater cooperation on European foreign and security policy. Our vision is to demonstrate that engaging in common European action remains the most effective way of protecting European citizens. But we will reach out beyond those already converted to our message, framing our ideas and calls for action in a way that resonates with key decision-makers and the wider public across Europe’s capitals. Mark Leonard, Director “ 9 November is one of these portentous dates which characterised German and European history. I feel you couldn’t have chosen a better day on which to launch the new European Council on Foreign Relations here in Berlin.” Frank-Walter Steinmeier (2007) President of the Federal Republic of Germany and former Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs ecfr.eu OUR LEADERSHIP The European Council on Foreign Mark Leonard Relations (ECFR) is an award-winning think-tank that aims to conduct Director cutting-edge independent research in pursuit of a coherent, effective, Mark is the Director and co-founder of ECFR. He was and values-based European foreign chairman of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda policy. Council on Geoeconomics until 2016, director of foreign policy at the Centre for European Reform, and director of We provide an exclusive meeting the Foreign Policy Centre. -

43. Møde Sigtede, Men Ikke Dømte Personer)

Tirsdag den 26. januar 2010 (D) 1 7) 1. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 90: Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om Det Centrale Dna-profil-regi- ster. (Frist for sletning af oplysninger om dna-profiler vedrørende 43. møde sigtede, men ikke dømte personer). Tirsdag den 26. januar 2010 kl. 13.00 Af justitsministeren (Brian Mikkelsen). (Fremsættelse 16.12.2009). Dagsorden 8) 1. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 91: Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om kreditaftaler og lov om mar- 1) 3. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 92: kedsføring. (Ændringer som følge af forbrugerkreditdirektivet). Forslag til lov om fond til grøn omstilling og erhvervsmæssig forny- Af justitsministeren (Brian Mikkelsen). else. (Fremsættelse 16.12.2009). Af økonomi- og erhvervsministeren (Lene Espersen). (Fremsættelse 16.12.2009. 1. behandling 12.01.2010. Betænkning 9) 1. behandling af beslutningsforslag nr. B 50: 19.01.2010. 2. behandling 21.01.2010. Lovforslaget optrykt efter 2. Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om en styrket indsats over for forbr- behandling). ydelser motiveret af offerets seksualitet, etnicitet m.v. (hadforbrydel- ser). 2) 3. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 94: Af Kamal Qureshi (SF) m.fl. Forslag til lov om særlige kompetenceudvidende forløb for nyuddan- (Fremsættelse 10.11.2009). nede. Af videnskabsministeren (Helge Sander). 10) 1. behandling af beslutningsforslag nr. B 55: (Fremsættelse 18.12.2009. 1. behandling 13.01.2010. Betænkning Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om pligt for børn under 12 år til at 19.01.2010. 2. behandling 21.01.2010. Lovforslaget optrykt efter 2. bære cykelhjelm. behandling). Af Pia Olsen Dyhr (SF) og Lone Dybkjær (RV) m.fl. -

90. Møde Behandling)

Tirsdag den 11. maj 2010 (D) 1 (Fremsættelse 03.03.2010. 1. behandling 23.03.2010. Betænkning 28.04.2010. 2. behandling 06.05.2010. Lovforslaget optrykt efter 2. 90. møde behandling). Tirsdag den 11. maj 2010 kl. 12.00 6) 3. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 150 A: Forslag til lov om ændring af ligningsloven, skattekontrolloven og lov om aktiv socialpolitik. (Fradrag for private donationer til forsk- Dagsorden ning m.v.). Af skatteministeren (Troels Lund Poulsen). 1) Fortsættelse af forespørgsel nr. F 40 [afstemning]: (2. behandling 06.05.2010. Lovforslaget optrykt efter 2. behandling). Forespørgsel til indenrigs- og sundhedsministeren om den kommu- nale økonomi. 7) 3. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 150 B: Af Rasmus Prehn (S), Flemming Bonne (SF), Margrethe Vestager Forslag til lov om ændring af ligningsloven. (Højere bundfradrag (RV) og Line Barfod (EL). ved udlejning af fritidsboliger). (Anmeldelse 07.04.2010. Fremme 09.04.2010. Første del af fore- Af skatteministeren (Troels Lund Poulsen). spørgslen (forhandlingen) 07.05.2010. Forslag til vedtagelse nr. V (2. behandling 06.05.2010. Lovforslaget optrykt efter 2. behandling). 69 af Rasmus Prehn (S), Flemming Bonne (SF), Margrethe Vestager (RV) og Line Barfod (EL). Forslag til vedtagelse nr. V 70 af Sophie 8) 3. behandling af lovforslag nr. L 147: Løhde (V), Hans Kristian Skibby (DF), Henrik Rasmussen (KF), Forslag til lov om ændring af våbenloven og krigsmaterielloven. Villum Christensen (LA), Christian H. Hansen (UFG) og Pia Christ- (Mærkning af skydevåben m.v.). mas-Møller (UFG)). Af justitsministeren (Lars Barfoed). (Fremsættelse 25.02.2010. 1. behandling 26.03.2010. Betænkning 2) 3. -

Pdf Dokument

Udskriftsdato: 29. september 2021 2011/1 BTB 46 (Gældende) Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om behandling af forhandlingsmandater i Folketinget Ministerium: Folketinget Betænkning afgivet af Europaudvalget den 1. juni 2012 Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om behandling af forhandlingsmandater i Folketinget [af Merete Riisager (LA) m.fl.] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet Beslutningsforslaget blev fremsat den 13. marts 2012 og var til 1. behandling den 25. maj 2012. Beslut- ningsforslaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Europaudvalget. Møder Udvalget har behandlet beslutningsforslaget i 2 møder. 2. Indstillinger og politiske bemærkninger Et flertal i udvalget (V, S, RV, SF og KF) indstiller forslaget til forkastelse. Et mindretal i udvalget (DF, EL og LA) indstiller forslaget til vedtagelse uændret. Liberal Alliance er af den opfattelse, at danskerne har to gode grunde til at opleve EU som fjernt. Den ene er en udpræget ulyst − blandt de gamle partier − til at tale åbent om, hvor EU er på vej hen og den anden, at EU-spørgsmål afgrænses til et særligt EU-reservat, der kun åbnes ved folkeafstemninger, eller når euroen er ved at ramle. Liberal Alliance mener, at Europaudvalget i praksis fungerer som en del af dette EU-reservat, og at det faktum, at mandatafgivelsen til EU afgives i Europaudvalget, er med til at hæmme en åben, kvalificeret og demokratisk debat om Europa. Liberal Alliance noterede, f.eks. i forbindelse med behandlingen af »sixpacken«, der øger den centrale overvågning og styringen af medlemslandenes økonomi, at det ellers magtfulde Finansudvalg ikke blev inddraget. Liberal Alliance anerkender, at Europaudvalget udgøres af engagerede ordførere, og at Europaudval- gets sekretariat er både hårdtarbejdende og velfungerende.