Some Considerations on Ice Navigation in the Polar Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISSN 2221—2698 Arkhangelsk 2015

ISSN 2221—2698 Arkhangelsk 2015. N18 Arctic and North. 2015. N 18 2 ISSN 2221—2698 Arctic and North. 2015. N 18 Multidisciplinary internet scientific journal © Northern (Arctic) Federal University named after M.V. Lomonosov, 2015 © Editorial board of the internet scientific journal “Arctic and North”, 2015 Published not less than four times per year The journal is registered at: Roskomnadzor as electronic periodical published in Russian and English. Registration certifi- cate of the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technologies and Mass Media El № FS77-42809 from November 26, 2010. The ISSN International Centre — world catalog of serials and ongoing resources. ISSN 2221— 2698, 23—24 March 2011. The system of Russian Science Citation Index (RSCI). License contract № 96-04/2011R from April 12, 2011. Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) — catalog of free access journals, 18.08.2013. The catalogs of international databases: EBSCO Publishing (USA) since December 2012; Global Se- rials Directory Ulrichsweb (USA) in October 2013. NSD — database of higher education in Norway (analog of Russian Higher Attestation Commis- sion) from February 2015. Founder — FSAEI HPE Northern (Arctic) Federal University named after M.V. Lomonosov. The editorial board staff of “Arctic and North” journal is published on the web site at: http://narfu.ru/aan/DOCS/redsovet.phpEditor-in-Chief — Yury Fedorovich Lukin, Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor, Honorary Worker of the higher school of the Russian Federation. Multidisciplinary internet scientific journal publishes articles in which the Arctic and the North are research objects, specifically in the following fields of science: history, economics, social sciences; political science (geopolitics); ecology. -

The North Atlantic Inflow to the Arctic Ocean: High-Resolution Model Study

ÔØ ÅÒÙ×Ö ÔØ The North Atlantic inflow to the Arctic Ocean: High-resolution model study Yevgeny Aksenov, Sheldon Bacon, Andrew C. Coward, A.J. George Nurser PII: S0924-7963(09)00211-5 DOI: doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2009.05.003 Reference: MARSYS 1863 To appear in: Journal of Marine Systems Received date: 30 July 2008 Revised date: 27 March 2009 Accepted date: 27 May 2009 Please cite this article as: Aksenov, Yevgeny, Bacon, Sheldon, Coward, Andrew C., Nurser, A.J. George, The North Atlantic inflow to the Arctic Ocean: High-resolution model study, Journal of Marine Systems (2009), doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2009.05.003 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT The North Atlantic Inflow to the Arctic Ocean: High-resolution Model Study ∗ YEVGENY AKSENOV , SHELDON BACON, ANDREW C. COWARD AND A. J. GEORGE NURSER National Oceanography Centre, Southampton Waterfront Campus, European Way, Southampton, SO14 3ZH, UK __________________________________________________________________ Abstract North Atlantic Water (NAW) plays a central role in the ocean climate of the Nordic Seas and Arctic Ocean. Whereas the pathways of the NAW in the Nordic Seas are mostly known, those into the Arctic Ocean are yet to be fully understood. -

Modern Processes Controlling the Sea Bed Sediment Formation in Barents Sea

Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vol. 11, EGU2009-7920-1, 2009 EGU General Assembly 2009 © Author(s) 2009 Modern processes controlling the sea bed sediment formation in Barents Sea I. Balanyuk (2), A. Dmitrievsky (1), S. Shapovalov (2), O. Chaikina (2), and T. Akivis (2) (2) P.P. Shirshov Institute of Oceanology, Russian academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russian Federation ([email protected], (1) Oil and Gas Institute Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia ([email protected] / Phone: +7 499-1357371 The Barents Sea is one of the key regions for understanding of the postglacial history of the climate and circulation of the World Ocean. There are the limits of warm North Atlantic waters penetration to the Arctic and a zone of interaction between Atlantic and Arctic waters. The Barents Se’s limits are the deep Norwegian Sea in the West, the Spitsbergen Island and the Franz Josef Land and the deep Nansen trough in the North, the Novaya Zemlya archipelago in the East and the North shore of Europe in the South. An analysis of Eurasian-Arctic continental margin shows correspondence between the rift systems of the shelf with those of the ocean. This relation can be observed in the central Arctic region. All the rift systems underlying the sediment basin are expressed in the sea bed relief as spacious and extensive graben valleys burnished by lobes. Two transverse trenches cross both shelf and continental slope, namely the Medvezhinsky trench between Norway and Spitsbergen in the West and the Franz Victoria trench between Spitsbergen and the Franz Josef Land in the North. -

Making the Russian Bomb from Stalin to Yeltsin

MAKING THE RUSSIAN BOMB FROM STALIN TO YELTSIN by Thomas B. Cochran Robert S. Norris and Oleg A. Bukharin A book by the Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. Westview Press Boulder, San Francisco, Oxford Copyright Natural Resources Defense Council © 1995 Table of Contents List of Figures .................................................. List of Tables ................................................... Preface and Acknowledgements ..................................... CHAPTER ONE A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SOVIET BOMB Russian and Soviet Nuclear Physics ............................... Towards the Atomic Bomb .......................................... Diverted by War ............................................. Full Speed Ahead ............................................ Establishment of the Test Site and the First Test ................ The Role of Espionage ............................................ Thermonuclear Weapons Developments ............................... Was Joe-4 a Hydrogen Bomb? .................................. Testing the Third Idea ...................................... Stalin's Death and the Reorganization of the Bomb Program ........ CHAPTER TWO AN OVERVIEW OF THE STOCKPILE AND COMPLEX The Nuclear Weapons Stockpile .................................... Ministry of Atomic Energy ........................................ The Nuclear Weapons Complex ...................................... Nuclear Weapon Design Laboratories ............................... Arzamas-16 .................................................. Chelyabinsk-70 -

Late Mesozoic-Cenozoic Evolution of the Barents Sea and Kara Sea Continental Margins

Polarforschung 68: 283 - 290, 1998 (erschienen 2000) Late Mesozoic-Cenozoic Evolution of the Barents Sea and Kara Sea Continental Margins By Eugeny E.Musatov l and Yulian E.Pogrebitskijl THEME 14: Circurn-Arctic Margins: The Search for Fits and Baikalian inliers, Scandinavian - West Spitsbergen epi-Cale Matches donian, Polar Ural - Pai-Khoi, Novaya Zemlya and Byrranga epi-Hercynian - Early Kimmerian orogens) and continental Summary: The most remarkable tectonic feature of Barents Sea and Kara Sea slopes and rises of Norwegian-Greenland (NGB) and Eurasian continental margins is a Cenozoic system of deep troughs anel grabens which (EB) basins. Young epicontinental Barents - northern Kara shelf follow Devonian-Jurassic paleorifts. These depressions are divided by a number of major domes and uplifts. The dominating tectonic process in the Barcnts-Kara marginal and Pechora, West Siberian intracontinental basins shelf was the successive degradation of an upliftedland within Svalbard-Franz occur on the continental margin. Each structure of this Josef Land-Severnaya Zemlya zone, which served as a terrigcnic source for morphostructural assemblage is characterised by its own spe scdimentary basins of southern and central parts of the continental margin, The cific features of Cenozoic tectonic and geodynamic regime. general neotectonic regime of the continental margin has caused strong uplift of orogens and shields as weil as shelfic archipelagos Svalbard, Franz Josef Land and Severnaya Zemlya and predominantly subsidence of intracontinental and The giant oil and gas fields discovered in the Barents and Kara marginal shelf basins, In general, Cenozoic tectonics were favourable for pres Seas shelves yield evidence for huge reserves ofhydrocarbons. ervation and re-fonning of oil & gas resourees on the shelf. -

NASA Selections

NNH06ZDA001N-IPY NASA HEADQUARTERS RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES IN SPACE AND EARTH SCIENCES –2006 NASA EARTH SCIENCE DIVISION A.16 THE INTERNATIONAL POLAR YEAR (IPY) This synopsis is for the NASA Cryosphere Program solicitation of the NASA Research Announcement (NRA) ROSES-2006 NNH06ZDA001N-IPY. This NRA offered opportunities for research to contribute to the objectives of the International Polar Year (IPY), for the period March 2007 to March 2009. From the NASA perspective, IPY will provide an international and interdisciplinary approach to understanding the behavior of these polar regions and their role in the broader Earth System, including the oceans, atmosphere, biosphere, cryosphere, and land surface. The IPY also offered the opportunity to study the Lunar and Martian poles, as well, in the spirit of exploration and discovery that was characteristic of the earlier IPYs and IGYs (International Geophysical Years). Details of the IPY and the U.S. IPY Program are available at: http://www.ipy.org/ and http://www.us-ipy.org/ respectively. Research was solicited under this announcement to deal with observational and modeling studies designed to understand polar processes and the links between the polar regions and the rest of the Earth System in a way that is scientifically and technologically interdisciplinary. As part of the planning for IPY, NASA solicited proposals in several areas: 1. Integrated analysis of multiple satellite data sets, enhanced validation of NASA satellite data sets in polar regions needed for improving their interpretation by models, and/or the integrated analysis of satellite and related suborbital data addressing the scientific questions defined by NASA in its Earth Science Enterprise Strategy (see Appendix at http://earth.nasa.gov/visions/ESE_Strategy2003.pdf) that can be addressed in the context of IPY. -

The Polar Data Catalogue: Best Practices for Sharing and Archiving Canada’S Polar Data

Data Science Journal, Volume 13, 30 October 2014 THE POLAR DATA CATALOGUE: BEST PRACTICES FOR SHARING AND ARCHIVING CANADA’S POLAR DATA J E Friddell1*, E F LeDrew1, and W F Vincent2 *1Canadian Cryospheric Information Network and Department of Geography, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1, Canada Email: [email protected] 2Centre d’études nordiques (CEN) et Département de biologie, Université Laval, Québec City, Québec G1V 0A6, Canada ABSTRACT The Polar Data Catalogue (PDC) is a growing Canadian archive and public access portal for Arctic and Antarctic research and monitoring data. In partnership with a variety of Canadian and international multi-sector research programs, the PDC encompasses the natural, social, and health sciences. From its inception, the PDC has adopted international standards and best practices to provide a robust infrastructure for reliable security, storage, discoverability, and access to Canada’s polar data and metadata. Current efforts focus on developing new partnerships and incentives for data archiving and sharing and on expanding connections to other data centres through metadata interoperability protocols. Keywords: Data management, Arctic, Antarctic, Canada, Cryosphere, Data repository, Interoperability, Metadata, Best practices, Standards 1 INTRODUCTION Scientific research in the Canadian Arctic has increased tremendously during the last decade, especially with development of large programmes such as the ArcticNet Network of Centres of Excellence of Canada (hereinafter ArcticNet) and Canada’s federal government programme for the International Polar Year 2007–2008 (IPY). With these programmes comes the need to build systems for effectively managing the collected data and to ensure proper preservation, stewardship, and access while respecting confidentiality requirements and researchers’ rights to publication (Vincent, Barnard, Michaud, & Garneau, 2010). -

Mapping and Monitoring of Benthos in the Barents Sea and Svalbard Waters: Results from the Joint Russian - Norwegian Benthic Programme 2006-2008

! " = This report should be cited as: Anisimova, N.A., Jørgensen, L.L., Lyubin, P.A. and Manushin, I.E. 2010. Mapping and monitoring of benthos in the Barents Sea and Svalbard waters: Results from the joint Russian - Norwegian benthic programme 2006-2008. IMR-PINRO Joint Report Series 1-2010. ISSN 1502-8828. 114 pp. Mapping and monitoring of benthos in the Barents Sea and Svalbard waters: Results from the joint Russian-Norwegian benthic programme 2006-2008 N.A. Anisimova1, L.L. Jørgensen2, P.A. Lyubin1 and I.E. Manushin1 1Polar Research Institute of Marine Fisheries and Oceanography (PINRO) Murmansk, Russia 2Institute of Marine Research (IMR) Tromsø, Norway The detritus feeding sea cucumber Molpodia borealis taken as by-catch in bottom trawling and now ready to be weighed counted and measured. Photo: Lis Lindal Jørgensen Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 2 Atlas of the macrobenthic species of the Barents Sea invertebrates .................................. 7 3 Benthic databases ............................................................................................................. 11 4 The by-catch survey ......................................................................................................... 17 4.1 Collection and processing methods .................................................................... 17 4.2 Results ............................................................................................................... -

Some Fishery Research Stations in the USSR, 1969

, LIBRARY 0, This series includes unpublished preliminary reports 150foRD Of CA*9 FISHERIES RESEARCH and data records not intended for general distribution. They should not be referred to in publications with- BIOLOGIC& STATION, out clearance from the issuing Board establishment and ST. JOHN'S, NEWFOUNDLAND, CANADA. without clear indication of their manuscript status. FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA MANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 1091 Some Fishery Research Stations in the USSR, 1969 by W. E. Ricker Biological Station, Nanaimo, B.C. June 1970 This series includes unpublished preliminary reports and data records not intended for general distribution. They should not be referred to in publications with out clearance from the issuing Board establishment and without clear indication of their manuscript status. FISHERIES RESEARCH BOll.BD OF CANADA MANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 1091 Some Fishery. Research Stations in the USSR~ 1969 by W. E. Ricker Biological Station, Nanaimo, B.C. June 1970 CONTENTS Foreword 2 Moscow Days 3 Account of a Visit to Fish and Fishery Facilities at Volgograd, with Incidental Information 29 Discursive Account of a Visit to the Institute for the Biology of Inland Waters at Borok 42 Summary Account of a Visit to Kiev 57 Visit to the State Research Institute for Lake and River Fisheries, Leningrad 69 A Trip to Murmansk 77 News from Siberia 87 Visit to Georgia (Gruzinskii SSR) 103 2 FOREWORD From mid-May to mid-November, 1969, I was in the USSR as exchange scientist with VNIRO, their central marine fisheries research laboratory. At intervals visits were made to other research centres. A series of informal reports concerning these was prepared from time to time, and these were distributed to FRB stations and laboratories. -

Akademik Tryoshnikov” I.E

ПРОБЛЕМЫ АРКТИКИ И АНТАРКТИКИ * 2019 * ТОМ 65 * № 3 УДК 551.465 DOI: 10.30758/0555-2648-2019-65-3-255-274 TRANSARKTIKA-2019: WINTER EXPEDITION IN THE ARCTIC OCEAN ON THE R/V “AKADEMIK TRYOSHNIKOV” I.E. FROLOV1, V.V. IVANOV1,2*, K.V. FILCHUK1, A.P. MAKSHTAS1, V.YU. KUSTOV1, I.A. MAHOTINA1, B.V. IVANOV1,3, A.V. URAZGILDEEVA3, V.L. SYOEMIN4, O.L. ZIMINA5, A.A. KRYLOV3,6, V.A. BOGIN6, V.Yu. ZAKHAROV6, S.A. MALYSHEV6, E.A. GUSEV6, P.E. BARYSHEV1, S.V. PILGAEV7, S.M. KOVALEV1, A.B. TURYAKOV1 1 — State Scientifi c Center of the Russian Federation Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute, St. Petersburg, Russia 2 — Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia 3 — St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia 4 — Southern Scientifi c Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Rostov-on-Don, Russia 5 — Murmansk Marine Biological Institute, Kola Sciencetifi c Center, Russian Academy of Sciences, Murmansk, Russia 6 — VNIIOkeangeologiya, St. Petersburg, Russia 7 — Polar Geophysical Institute, Apatity, Russia *[email protected] ТРАНСАРКТИКА-2019: ЗИМНЯЯ ЭКСПЕДИЦИЯ В СЕВЕРНЫЙ ЛЕДОВИТЫЙ ОКЕАН НА НЭС «АКАДЕМИК ТРЁШНИКОВ» И.Е. ФРОЛОВ1, В.В. ИВАНОВ1,2*, К.В. ФИЛЬЧУК1, А.П. МАКШТАС1, В.Ю. КУСТОВ1, И.А. МАХОТИНА1, Б.В. ИВАНОВ1,3, А.В.УРАЗГИЛЬДЕЕВА3, В.Л. СЁМИН4, О.Л. ЗИМИНА5, А.А. КРЫЛОВ3,6, В.А. БОГИН6, В.Ю. ЗАХАРОВ6, С.А. МАЛЫШЕВ6, Е.А.ГУСЕВ6, П.Е. БАРЫШЕВ1, С.В. ПИЛЬГАЕВ7, С.М. КОВАЛЕВ1, А.Б. ТЮРЯКОВ1 1 — ГНЦ РФ Арктический и антарктический научно-исследовательский институт, Санкт-Петербург, Россия 2 — Московский государственный университет им. -

Tectonic History of Tertiary Sedimentation of Svalbard

Tectonic history of Tertiary sedimentation of Svalbard JU. JA. LIVSIC Livsic, Ju. Ja.: Tectonic history of Tertiary sedimentation of Svalbard. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, Vol. 72, pp. 121-127. Oslo 1992. ISSN 0029-196X. Svalbard's Tertiary sedimentary record is important for the understanding of the Tertiary evolution of the entire Svalbard surroundings. Two main phases of Palaeogene sedimentation and establishment of structures have been recognized, both taking place in the West Spitsbergen trough. The first one (transgressive-regressive cycle) resulted in the accumulation of Palaeocene Eocene deposits, while the second one (regressive phase subsequent to the mid-late Eocene uplift) is represented by Eocene Oligocene deposits. During the second and tectonically more active phase, sedimentation also started in small isolated grabens in the centre of the west coast horst-like uplift, e.g. in Forlandsundet-Bellsund (mid-Eocene to early Oligocene), in Renardodden and in Kongsfjorden (early Oligocene). The sediments - like those of the second phase of the West Spitsbergen trough - indicate an intense tectonic regime that finally resulted in thrust tectonics along the west coast of Spitsbergen in connection with crustal movements in the Atlantic Ocean. The mid-late Oligocene conglomerates of the Sarsbukta Formation in the Forlandsundet graben, the youngest Palaeogene sediments in Svalbard, pro bably mark the beginning of a third, post-thrust Tertiary phase ( Oligocene Neogene). Similar sediments lill in the perioceanic troughs to the west of Svalbard. At the end of the Neogene, Svalbard underwent a general uplift against the background of descending movements within the perioceanic troughs. Ju. Ja. LivJic, VNII Okeangeologija, Moika 120, SU-190121 Leningrad, USSR. -

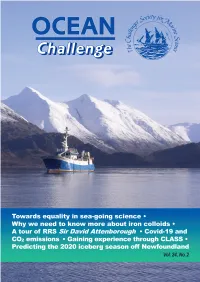

Ocean Challenge Aims to Keep Its Readers up to Date Formerly Open University with What Is Happening in Oceanography in the UK and the Rest of Europe

Volume 24, No.2, 2018 (published 2020) EDITOR SCOPE AND AIMS Angela Colling Ocean Challenge aims to keep its readers up to date formerly Open University with what is happening in oceanography in the UK and the rest of Europe. By covering the whole range of marine-related sciences in an accessible style it EDITORIAL BOARD should be valuable both to specialist oceanographers Chair who wish to broaden their knowledge of marine Stephen Dye sciences, and to informed lay persons who are Cefas and University of East Anglia concerned about the oceanic environment. Barbara Berx NB Ocean Challenge can be downloaded from the Marine Scotland Science Challenger Society website free of charge, but members can opt to receive printed copies. Emma Cavan Imperial College London For more information about the Society, or Philip Goodwin for queries concerning individual or library National Oceanography Centre, Southampton subscriptions to Ocean Challenge, please see the Laura Grange Challenger Society website (www.challenger- University of Bangor society.org.uk) Katrien Van Landeghem University of Bangor INDUSTRIAL CORPORATE MEMBERSHIP For information about corporate membership, please contact Terry Sloane [email protected] The views expressed in Ocean Challenge are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those ADVERTISING of the Challenger Society or the Editor. For information about advertising, please contact the Editor (see inside back cover). AVAILABILITY OF BACK ISSUES OF OCEAN CHALLENGE For information about back issues, please contact the Editor (see inside back cover). DATA PROTECTION ACT, 1984 (UK) © Challenger Society for Marine Science, 2020 Under the terms of this Act, you are informed that this magazine is sent to you through the use of a ISSN 0959-0161 Printed by Halstan Printing Group computer-based mailing list.