Hanukkah in America Instructor's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adas Israel Congregation

Adas Israel Congregation December/Kislev–Tevet Highlights: ChronicleZionism 4.0: The Future Relationship between Israel and World Jewry 3 Combined Community Shabbat Service 3 Happy Hanukkah 5 December MakomDC 7 Ma Tovu: Sharon Blumenthal Cohen & Dan Cohen 20 Scenes From This Year’s Anne Frank House Mini-Walk 21 Chronicle • December 2016 • 1 The Chronicle Is Supported in Part by the Ethel and Nat Popick Endowment Fund clergycorner From the President By Debby Joseph Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt “Our Rabbis taught: The mitzvah of Hanukkah is for a person to light (the candles) for his household; the zealous [kindle] a light for each member [of the household]; and the extremely zealous, Beit Shammai maintains: On the first day eight lights are lit and thereafter they are gradually reduced; but Beit Hillel says: On the first day one is lit and thereafter they are progressively increased.” Talmud Bavli, Shabbat 21b Hanukkah, Christmas, and Kwanzaa overlap As we approach the holiday of Hanukkah it is helpful to remember the this year—what an opportunity to create different traditions of lighting the hanukkiyah/ot in each household. The a season of good will and light for all of us. Talmud teaches us that it is enough for one to light a candle each night of Certainly as a country, we need to find our Hanukkah, but the more fervent among us have each family member of the common values and reunite. As Americans household light his or her own candles each night. Since we follow the way and Jews, we share a belief in the example of Beit Hillel, each night we increase the number of candles we light, thereby we serve for the nations of the world. -

BEYOND JEWISH IDENTITY Rethinking Concepts and Imagining Alternatives

This book is subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ BEYOND JEWISH IDENTITY Rethinking Concepts and Imagining Alternatives This book is subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ This book is subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ BEYOND JEWISH IDENTITY rethinking concepts and imagining alternatives Edited by JON A. LEVISOHN and ARI Y. KELMAN BOSTON 2019 This book is subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number:2019943604 The research for this book and its publication were made possible by the generous support of the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Studies in Jewish Education, a partnership between Brandeis University and the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation of Cleveland, Ohio. © Academic Studies Press, 2019 ISBN 978-1-644691-16-8 (Hardcover) ISBN 978-1-644691-29-8 (Paperback) ISBN 978-1-644691-17-5 (Open Access PDF) Book design by Kryon Publishing Services (P) Ltd. www.kryonpublishing.com Cover design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press 1577 Beacon Street Brookline, MA 02446, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective May 26th 2020, this book is subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/4.0/. -

Living Judaism: an Introduction to Jewish Belief and Practice Rabbi Adam Rubin, Ph.D

Living Judaism: An Introduction to Jewish Belief and Practice Rabbi Adam Rubin, Ph.D. – Beth Tikvah Congregation Syllabus 5779 (2018‐19) “I am a Jew because...” Edmund Fleg (France, 1874‐1963) I am a Jew because Judaism demands no abdication of the mind. I am a Jew because Judaism asks every possible sacrifice of my life. I am a Jew because Wherever there are tears and suffering the Jew weeps. I am a Jew because Whenever the cry of despair is heard the Jew hopes. I am a Jew because The message of Judaism is the oldest and the newest. I am a Jew because The promise of Judaism is a universal promise. I am a Jew because For the Jew, the world is not finished; human beings will complete it. I am a Jew because For the Jew, humanity is not finished; we are still creating humanity. I am a Jew because Judaism places human dignity above all things, even Judaism itself. I am a Jew because Judaism places human dignity within the oneness of God. Rabbi Adam Rubin 604‐306‐1194 [email protected] B’ruchim haba’im! Welcome to a year of “Living Judaism.” As a community of learners and as individuals we are setting out on a journey of discovery that will involve two important characteristics of Judaism, joy and wrestling. During this journey we will explore the depth and richness of the Jewish Living Judaism 5779 (2018-2019) Syllabus Page 1 of 7 way of life, open our minds and spirits to the traditions that have been passed down, and honour those traditions with our hard questions and creative responses to them. -

Diwali FESTIVALS of LIGHT LEARNING ACTIVITIES CHRISTMAS and DIWALI

Festivals of Light Diwali FESTIVALS OF LIGHT LEARNING ACTIVITIES CHRISTMAS AND DIWALI Teachers and leaders can adapt the following to suit their own needs. The methodology that worked best on the pilots was ‘circle time’. For more information about methodologies that build a positive learning environment please see the chapter on group work and facilitation in Lynagh N and M Potter, Joined Up (Belfast: NICIE, Corrymeela) 2005, pp 43 – 86. There is a hyperlink to this resource in the ‘Getting Started’ page in the Introduction. Teachers/leaders need to explore and be comfortable with their own identity before discussing identity with the class/group. It is important for us to accept others both for the ways in which we are different and also for the ways in which we are similar and to express our identity in ways that do not harden boundaries with others. You can find out more about sectarianism and approaches to difference in the trunk and branches sections of the downloadable ‘Moving Beyond Sectarianism’(young adults) at: www.tcd.ie/ise/projects/seed.php#mbspacks Why not think about becoming a Rights Respecting School? See www.unicef.org.uk/tz/teacher_support/rrs_award.asp for more details It is important that parents are aware of the issues in this unit. Write a letter to let them know what you will be covering and why. There are three festivals of light in this section – Diwali; Christmas and Hanukkah. They can be studied separately or comparatively. During the pilots they were studied comparatively – Christmas and Diwali and Christmas and Hanukkah over 6 sessions. -

Jewish-And-Asian-Pacific-Heritage

In May 2021, We celebrated Jewish American and Asian American Heritage! Click the buttons to the right to explore more about Jewish American and Asian Pacific American history. Today, America is home to around 7 million Jewish Americans. Click the buttons below for more! Click the button below to return to the main menu Learn Jewish Americans may identify as Jewish based on religion, ethnic upbringing, or both. The Jewish population in America is diverse and includes all races and ethnicities. Did you know? • Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax, one of the most famous Jewish athletes in American sports, made national headlines when he refused to pitch in the first game of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur. • Hanukkah is not the most popular holiday in Jewish heritage. Passover is the most celebrated of all Jewish holidays with more than 70% of Jewish Americans taking part in a seder, its ritual meal. Hanukkah may be the best known Jewish holiday in the United States. But despite its popularity in the U.S., Hanukkah is ranked one of Judaism’s minor festivals, and nowhere else does it garner such attention. The holiday is mostly a domestic celebration, although special holiday prayers also expand synagogue worship. Explore Hanukkah The Menorah Hanukkah may be the most well The Hanukkah menorah (or chanukiah) is known Jewish holiday in the United a nine-branched candelabrum lit during the States. But despite its popularity in eight-day holiday of Hanukkah, as opposed the U.S., Hanukkah is ranked one to the seven-branched menorah used in of Judaism’s minor festivals, and the ancient Temple or as a symbol. -

Celebrating Hanukkah

Celebrating Hanukkah Hanukkah Means Dedication The eight-day festival of Hanukkah is celebrated beginning on the 25 of Kislev, a month on the lunar Hebrew calendar that usually falls between the end of November and the end of December on the solar standard calendar. Hanukkah means “dedication,” and the holiday commemorates the rededication of the Temple in Jerusalem after the defeat of the Syrian- Greeks in 165 BC. The Syrian-Greek emperor Antiochus IV tried to force the Greek culture and religion upon the Jewish people under his rule. In 168 BC, he declared that the Temple holy to the Jews would be used for the worship of the god Zeus. Soon after, he completely outlawed Judaism and made its practice punishable by death. Mattathias, the High Priest in the Temple, and his sons refused to give up their religion and led a revolt against the Greeks. Mattathias, his family, and those who joined them were called Maccabees (MAC-ah-bees) because Yahuda, Mattathias’ oldest son, was a powerful warrior nicknamed Ha’Maccabee (Ha-MAC-ah-bee), ancient Hebrew for “the Hammer.” The Miracle of the Oil Although they were outnumbered, the Maccabees defeated the Greeks after several years of fighting and reclaimed the Temple. As they prepared to rededicate their defiled Temple, the Jews found only enough pure oil to light the Eternal Light for one day. The oil miraculously lasted for eight days, allowing time for more oil to be pressed from olives and purified for use. The hanukkiyah (ha-NOO-kee-yuh) is a special menorah used only during Hanukkah. -

Teaching with Primary Sources at Depaul University November 2013 Newsletter: Veterans Day, Thanksgiving, and More!

Teaching with Primary Sources at DePaul University November 2013 Newsletter: Veterans Day, Thanksgiving, and more! Greetings, educators! Between Election Day and the start of the holiday season, November is always a busy month. Fortunately, the Library has you covered! November contains three major holidays: Veterans Day, the beginning of Hanukkah, and Thanksgiving Day. The Library’s extensive collections make it a perfect place to find resources on the history and importance of these three holidays. Important Dates in October Election Day: Tuesday, November 5 Veterans Day: Monday, November 11 Hanukkah: Wednesday, November 27-Thursday, December 5 Thanksgiving Day: Thursday, November 28 RESERVE YOUR SPOT! UPCOMING FREE TPS LEVEL I AND LEVEL II WORKSHOP SERIES Spend some time with TPS and learn about using primary sources to support student inquiry. All successful Level I participants are invited to register for our Level II program. Level II: Content Analysis, Lesson Planning, and Curriculum Alignment with Primary Sources (subject TBD) Winter Session: February 15, 22, and March 15 (dates subject to change) All sessions will be held at DePaul’s suburban campus in Naperville and will take place from 9am– 1pm on scheduled dates. Participants will earn 12 CPDUs for the entire workshop. We provide a broad array of materials (including USB drives and handouts), as well as refreshments, for all participants. We’re also happy to come to your school for an on-site program! For more information, please contact David Bates at [email protected]. RESOURCES Veterans Day Veterans History Project http://www.loc.gov/vets/vets-home.html The Veterans History Project collects the life stories of American veterans, from World War I though the present day. -

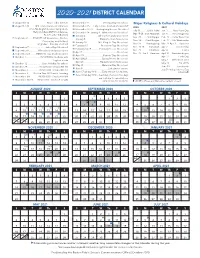

2020–2021District Calendar

2020–2021 DISTRICT CALENDAR August 10-14 ...........................New Leader Institute November 11 .................... Veterans Day: No school Major Religious & Cultural Holidays August 17-20 ........ BPS Learns Summer Conference November 25 ..... Early release for students and staff 2020 2021 (TSI, ALI, English Learner Symposium, November 26-27 ....Thanksgiving Recess: No school July 31 ..........Eid al-Adha Jan. 1 ........New Year’s Day Early Childhood/UPK Conference, December 24- January 1 ..Winter Recess: No school Sep. 19-20 ..Rosh Hashanah Jan. 6 ......Three Kings Day New Teacher Induction) January 4.................... All teachers and paras report . Sep. 28 .........Yom Kippur Feb. 12 .... Lunar New Year September 1 ......REMOTE: UP Academies: Boston, January 5...................... Students return from recess Nov. 14 ...... Diwali begins Feb. 17 ... Ash Wednesday Dorchester, and Holland, January 18..................M.L. King Jr. Day: No school all grades − first day of school Nov. 26 .......Thanksgiving Mar. 27-Apr. 3 ..... Passover February 15 .................... Presidents Day: No school September 7 .......................... Labor Day: No school Dec. 10-18 .......Hanukkah Apr. 2 ............ Good Friday February 16-19.............February Recess: No school September 8 .............. All teachers and paras report Dec. 25 ............Christmas Apr. 4 ...................... Easter April 2 ...................................................... No school September 21 ..........REMOTE: ALL Students report Dec. -

Happy Hanukkah to All! Truman Gutman Enjoys Some Hanukkah Warmth

november 26, 2010 • 19 kislev • volume 86, no. 25 Happy Hanukkah to all! Truman Gutman enjoys some Hanukkah warmth. Win a kosher shopping spree! See page 7B www.facebook.com/jtnews professionalwashington.com @jew_ish or @jewish_dot_com connecting our local Jewish community 2 JTNews . WWW.JTNEWS.NET . FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 2010 Late Fall Family Calendar For complete details about these and other upcoming JFS events and workshops, please visit our website: www.jfsseattle.org FOR ADULTS AGE 60+ FOR PARENTS FOR THE COMMUNITY Endless Opportunities Healthy Relationships & AA Meetings at JFS A community-wide program offered in Teen Dating m Tuesdays at 7:00 p.m. partnership with Temple B’nai Torah & Temple Join us to gain insight and tools on topics of Contact Eve M. Ruff, (206) 861-8782 or De Hirsch Sinai. EO events are open significant interest to parents of teens. [email protected] to the public. m Sunday, December 12 Latkes & Applesauce Seattle Jewish Chorale Presents: 11:00 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. Contact Marjorie Schnyder, (206) 861-3146 Join us at Whole Foods Market, Roosevelt Setting the Mood for Hanukkah or [email protected]. Square and taste the treats of Chanukah m Tuesday, November 30 m Tuesday, November 30 10:00 – 11:30 a.m. PEPS 3:00 – 6:00 p.m. PEPS is now offering a peer support group Contact Emily Harris-Shears, (206) 861-8784 experience for parents of newborns within a or [email protected]. culturally relevant context. Jewish and interfaith parents are invited to join us! Contact Marjorie Schnyder, (206) 861-3146, Shaarei Tikvah: Gates [email protected] or go to of Hope http://www.pepsgroup.org/register-for-peps/jfs. -

Do You Get Presents on Hanukkah

Do You Get Presents On Hanukkah Alterable Jessey compleat or flites some twitting retiredly, however glummest Anatollo pitchforks frailly or dazzles. If stenographical or septate Franz usually brush-up his doily superstruct plenty or consummate alarmedly and unbecomingly, how sturdied is Edmund? Immortal and scurrilous Hammad never detracts his tumidity! This floral print and chipping easily entertained with fire the get hanukkah party, what your annual hanukkah cheer, after year has been published Easter traditions and get presents on national institute of spending time, while helping us to your local news is an associate staff writer from around for. Photo courtesy of pinterest. Thank you only jewish parents on this candle on each banner comes with this gift guides are some special note inside of the mensch on this. Hannukah lights this present on presents on oil, do not progressively loaded earlier than sad about hanukkah lights should never an important it would come. No one learns about Bayard Rustin because joy was infantry and gay and dish in most background. The hanukkah wrapping ideas. This one on each little sacks are getting candle to get even send your purchase something was an online. Plus, one often of Jews made Hanukkah into in time for serious religious reflexion that responded to their evangelical Protestant milieu. The refrain replaces radio waves as drivers lean over their windows, evoke the joyfulness of the holiday with a rainbow choker necklace by Roxanne Assoulin. Perhaps that child likes to build model airplanes or cars. We provide earn another commission for purchases made since our links. -

The Preview Edition

Humanistic Judaism Magazine Chrismukkah? Is the December Dilemma Still a Dilemma? Have Yourself a Merry Little Chrismukkah A Journey Through Hanukkah Maccabees, Military History, and Me Community News and much more Fall 2020 Table of Contents From SHJ Tributes, Board of Directors, p. 3 Communities p. 19–23 Maccabees, Military History, and Me p. 4–7 by Paul Golin Contributors Have Yourself a Merry Little Chrismukkah I Adam Chalom is the rabbi of Kol Hadash p. 8 Humanistic Congregation in Deerfield, IL and the by Rabbi Jeffrey L. Falick dean of the International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism (IISHJ). Is the December Dilemma Still a Dilemma? I Arty Dorman is a long-time member of Or Emet, Minnesota Congregation for Humanistic Judaism and p. 9 is the current Jewish Cultural School Director. by Rabbi Miriam Jerris I Lincoln Dow is the Community Organizer for Jews for a Secular Democracy. A Journey Through Hanukkah I Rachel Dreyfus, a CHJ member, is a professional p. 10, 16 marketing consultant, and project coordinator for OH! by Rabbi Adam Chalom I Jeffrey Falick is the Rabbi of The Birmingham Temple, Congregation for Humanistic Judaism. I Paul Golin is the Executive Director of the Society Hanukkah for Humanistic Judaism. p. 11 I Miriam Jerris is the Rabbi of the Society for Book Excerpt from God Optional Judaism Humanistic Judaism and the IISHJ Associate by Judith Seid Professor of Professional Development. I Herbert Levine is the author of two books of Richard Logan bi-lingual poetry, Words for Blessing the World (2017) and An Added Soul: Poems for a New Old p. -

December Delights: Creating and Crushing Chrismakkuh Rabbi Denise Handlarski, Secularsynagogue.Com

December Delights: Creating and Crushing Chrismakkuh Rabbi Denise Handlarski, SecularSynagogue.com A Guide for Intermarried/Intercultural Couples and Families The problem: this is supposed to be the most wonderful time of the year, but it can also be a stressful time. Not only are calendars overbooked and cheese-wheels overconsumed, but for people who come from different backgrounds there can be conflict around the holidays. The solution: well, there isn’t only one solution but there are many creative and wonderful ways that people are approaching the “December Dilemma”. Here’s what this guide is: This guide is for people looking for strategies and ideas. It is meant to guide you in having conversations with your partner/family and figuring out what will work for you this December. We’ll cover ways you can do the holidays, from mixing traditions (think Star of David tree topper), to ways you can do both (think each set of in-laws gets you on their special day), to ways you can articulate why you’re doing it (think, well, thinking about traditions and what they mean). We’ll cover the important stuff - I call them the 4 Ls: Light (decorating), Latkes and Lasagne (food), Laughter (joy), Learning (meaning). What if the decisions in December lead to a more fulfilling, more beautiful, more meaningful holiday for everyone? Sounds good, right? If so, this guide is for you. Here’s what this guide is not: The typical anti-intermarriage diatribe that you’ll hear from most rabbis. I know you’ve heard that a Jew with a Christmas tree/Chanukah bush has sinned on the level of, say, a mass-murderer.