Sounds from the Other Side

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evenings for Educators 2018–19

^ Education Department Evenings for Educators Los Angeles County Museum of Art 5905 Wilshire Boulevard 2018–19 Los Angeles, California 90036 Charles White Charles White: A Retrospective (February 17–June 9, involved with the WPA, White painted three murals in 2019) is the first major exhibition of Charles White’s Chicago that celebrate essential black contributions work in more than thirty-five years. It provides an to American history. Shortly thereafter, he painted the important opportunity to experience the artist’s mural The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in work firsthand and share its powerful messages with America (1943), discussed in detail in this packet. the next generation. We are excited to share the accompanying curriculum packet with you and look After living in New York from 1942 until 1956, White forward to hearing how you use it in your classrooms. moved to Los Angeles, where he remained until his passing in 1979. Just as he had done in Chicago Biography and New York, White became involved with local One of the foremost American artists of the twentieth progressive political and artistic communities. He century, Charles White (1918–1979) maintained produced numerous lithographs with some of Los an unwavering commitment to African American Angeles’s famed printing studios, including Wanted subjects, historical truth, progressive politics, and Poster Series #14a (1970), Portrait of Tom Bradley social activism throughout his career. His life and (1974), and I Have a Dream (1976), which are work are deeply connected with important events included in this packet. He also joined the faculty and developments in American history, including the of the Otis Art Institute (now the Otis College of Great Migration, the Great Depression, the Chicago Art and Design) in 1965, where he imparted both Black Renaissance, World War II, McCarthyism, the drawing skills and a strong social consciousness to civil rights era, and the Black Arts movement. -

A Case Study of the Timberland Corporation Jesse Levin

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 1998 Transforming corporations to transform society : a case study of the Timberland Corporation Jesse Levin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Leadership Studies Commons Recommended Citation Levin, Jesse, "Transforming corporations to transform society : a case study of the Timberland Corporation" (1998). Honors Theses. 1259. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1259 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. j UNIVERSITYOF RICHMOND LIBRARIES i 111111111~1mn~~~,~~m1rrn11 Transforming Corporations to Transform Society: A Case Study of the Timberland Corporation By Jesse Levin Jessica Horan Senior Project Jepson School of Leadership Studies University of Richmond Richmond, Virginia May,1998 Transforming Corporations to Transform Society: A Case Study of The Timberland Corporation By Jesse Levin Jessica Horan Senior Project Jepson School of Leadership Studies University of Richmond Richmond, Virginia May 1998 Table of Contents I. Introduction 2 II. Literature Review 5 Historical Perspective 6 Economic Perspective 9 The Emergence of Social Enterprise 12 The Timberland Example 17 A Framework for Social Enterprise 18 III. Methodology 23 Limitations 30 IV. Results 33 Sample Group 36 Question 1. 37 Does Timberland's approach to capacity building facilitate multiple levels of transformation? If so, how? Question 2. 40 If Timberland effects internal transformation, does this change the external environment? If so, how? Question 3. -

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

The Concert Hall As a Medium of Musical Culture: the Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19Th Century

The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century by Darryl Mark Cressman M.A. (Communication), University of Windsor, 2004 B.A (Hons.), University of Windsor, 2002 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Darryl Mark Cressman 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Darryl Mark Cressman Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) Title of Thesis: The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century Examining Committee: Chair: Martin Laba, Associate Professor Andrew Feenberg Senior Supervisor Professor Gary McCarron Supervisor Associate Professor Shane Gunster Supervisor Associate Professor Barry Truax Internal Examiner Professor School of Communication, Simon Fraser Universty Hans-Joachim Braun External Examiner Professor of Modern Social, Economic and Technical History Helmut-Schmidt University, Hamburg Date Defended: September 19, 2012 ii Partial Copyright License iii Abstract Taking the relationship -

Khalid Releases “Otw” Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign & 6Lack Today—Click Here to Listen Khalid Nominated for Five 2018 Billboard

KHALID RELEASES “OTW” FEAT. TY DOLLA $IGN & 6LACK TODAY—CLICK HERE TO LISTEN KHALID NOMINATED FOR FIVE 2018 BILLBOARD MUSIC AWARDS (Los Angeles, CA)—Today, Multi-platinum global superstar Khalid releases a brand-new track entitled “OTW” featuring Ty Dolla $ign and 6lack. The song is available now at all digital retail providers via Right Hand Music Group/RCA Records. Click HERE to listen. This past Tuesday, Khalid appeared on the Today Show (Click HERE) to announce the 2018 Billboard Music Award nominations for which he has been nominated for five awards including Top New Artist, Top R&B Artist, Top R&B Male Artist, Top R&B Album for American Teen, and Top R&B Song for “Young Dumb & Broke.” Khalid’s most recent release “Love Lies” with Keep Cool/RCA Records’ Normani is off to an explosive start having debuted at #43 on the Billboard Hot 100 and it has already received over 200 million streams worldwide since its release on February 14th. The track, which was just certified GOLD by the RIAA, is garnering critical acclaim with MTV calling it “a match made in musical heaven” and The FADER calling it a “slow-burning R&B ballad”. Since its release, the track has racked up over 150 million streams on Spotify alone, and the song’s official video has over 30 million views on YouTube. “Love Lies” also broke the Top 5 on the streaming platform’s US (#2) and Global (#3) Viral Charts. Additionally, Khalid he will be hitting the road again on “The Roxy Tour”, which will be making a number of stops in major cities including Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Philadelphia. -

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No

Institute for Studies In American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No. 2 Spring 2005 Jungle Jive: Jazz was an integral element in the sound and appearance of animated cartoons produced in Race, Jazz, Hollywood from the late 1920s through the late 1950s.1 Everything from big band to free jazz and Cartoons has been featured in cartoons, either as the by soundtrack to a story or the basis for one. The studio run by the Fleischer brothers took an Daniel Goldmark unusual approach to jazz in the late 1920s and the 1930s, treating it not as background but as a musical genre deserving of recognition. Instead of using jazz idioms merely to color the musical score, their cartoons featured popular songs by prominent recording artists. Fleischer was a well- known studio in the 1920s, perhaps most famous Louis Armstrong in the jazz cartoon I’ll Be Glad When for pioneering the sing-along cartoon with the You’ re Dead, You Rascal You (Fleischer, 1932) bouncing ball in Song Car-Tunes. An added attraction to Fleischer cartoons was that Paramount Pictures, their distributor and parent company, allowed the Fleischers to use its newsreel recording facilities, where they were permitted to film famous performers scheduled to appear in Paramount shorts and films.2 Thus, a wide variety of musicians, including Ethel Merman, Rudy Vallee, the Mills Brothers, Gus Edwards, the Boswell Sisters, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong, began appearing in Fleischer cartoons. This arrangement benefited both the studios and the stars. -

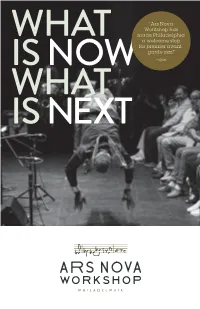

“Ars Nova Workshop Has Made Philadelphia a Welcome Stop For

“Ars Nova Workshop has made Philadelphia a welcome stop WHAT for premier avant- garde jazz." IS NOW —Spin WHAT IS NEXT “Curatorial brilliance” THIS IS —Downbeat OUR Mission AND THIS IS What WE DO Through collaboration and passionate investment, elevates the profile and expands the boundaries of jazz and contemporary music in Philadelphia. We present, on average, 40+ concerts per + year, featuring the biggest names in jazz and Concerts a year contemporary music. Sold Out More than half of our concerts are sold-out shows. We operate through partnerships—with venues, other non-profits, and local and national makers, visionaries, and creatives. We present in spaces throughout Philadelphia with a wide range of capacities, from 100 to 1,300 and more. We are masters at matching the artist with the venue, creating rich context and the appropriate environment for deep listening. OUR CURatoRial and PROGRamminG AMBitions Our logo incorporates a reproduction of a musical line: the iconic title riff from John Coltrane’s manuscript of “A Love Supreme.” While Ars Nova is indebted to this piece and the moment it represents for many reasons, we are especially drawn to the unassuming “ETC.” at the end. Think of everything that “ETC.” can do, promise, and point to: “A Love Supreme” takes off and becomes a new entity, spreading love and possibility and healing and joy and curiosity and discovery and a deeply spiritual present—no longer “just” a phenomenal piece of music that was recorded in a studio one day, but an anthem, a call to a future, a brain- seed in the form of an ear-worm. -

R&B/ -NOP Timbaland Makes a `Proposal'

R&B/ -NOP Timbaland Makes A `Proposal' Rapper Says Duo's Second Project On Blackground Is His Last As An Artist BY RASHAUN HALL Timbaland says the CD will be his understanding how it works and NEW YORK- Timing is everything last as an artist. how the money is made." when it comes to releasing a record. For Magoo, who found himself Working with renewed focus, the Just ask Timbaland & Magoo, whose grappling with newfound fame after duo crafted Indecent Proposal, a 15- and The Blues,. BlackgroundNirgin sophomore proj- track set featuring guest appear- ect, Indecent Proposal, is now set for ances by Aaliyah, Ludacris, Jay -Z, SNOOP'S NEW HOME: Snoop Dogg is Backstage after the Atlanta show, a Nov. 20 release after a long delay. and Tweet, among others. Magoo setting up shop at MCA Records. But Wright commented on her desire for "I turned [the album] in a year - credits Timbaland with matching the former No Limit/Priority rapper onstage spontaneity. "I'm just being and -a -half ago, and it's just [now] artists to its tracks. still has one more studio album under me," she says. "It's easy. I wrote a coming out," a frustrated Timbaland "He has an idea of what direction that contract before he can exit. The bunch of songs that I really like, and I says. "And now we're in a recession - each song should go in," Magoo says. MCA deal also includes Snoop Dogg's have some very capable musicians and it doesn't make sense." "It has a lot to do with the concept Doggy Style Records, formerly distrib- vocalists helping me create the colors The delay was partially due to and who can come up with a good uted by TVT, and the production of and the pictures that I want onstage.