Species Assessment for Eastern Long-Tailed Salamander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Virginia Streamside Salamander Guilds and Environmental Variables with an Emphasis on Pseudotriton Ruber Ruber Kathryn Rebecca Pawlik

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2008 West Virginia Streamside Salamander Guilds and Environmental Variables with an Emphasis on Pseudotriton ruber ruber Kathryn Rebecca Pawlik Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Pawlik, Kathryn Rebecca, "West Virginia Streamside Salamander Guilds and Environmental Variables with an Emphasis on Pseudotriton ruber ruber" (2008). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 780. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. West Virginia Streamside Salamander Guilds and Environmental Variables with an Emphasis on Pseudotriton ruber ruber Thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Biological Sciences By Kathryn Rebecca Pawlik Thomas K. Pauley, Committee Chair Frank Gilliam Jessica Wooten Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia Copyright April 2008 Abstract Amphibian distributions are greatly influenced by environmental variables, due in part to semi-permeable skin which makes amphibians susceptible to both desiccation and toxin absorption. This study was conducted to determine which streamside salamander species were sympatric and how environmental variables may have influenced habitat choices. One hundred sixty streams were surveyed throughout 55 counties in West Virginia during the summer of 2007. At each site, a 10 m2 quadrat was established around a central aquatic habitat. -

The Natural History of Cave-Associated Populations of Eurycea L

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 1-1-2009 The aN tural History of Cave-Associated Populations of Eurycea l. longicauda with Notes on Sympatric Amphibian Species Kevin Wayne Saunders [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Behavior and Ethology Commons Recommended Citation Saunders, Kevin Wayne, "The aN tural History of Cave-Associated Populations of Eurycea l. longicauda with Notes on Sympatric Amphibian Species" (2009). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 298. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Natural History of Cave-Associated Populations of Eurycea l. longicauda with Notes on Sympatric Amphibian Species Thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science Biological Sciences by Kevin Wayne Saunders Thomas K. Pauley, Committee Chair Dan Evans, Committee Member Tom Jones, Committee Member May, 2009 Abstract The Natural History of Cave-Associated Populations of Eurycea l. longicauda with Notes on Sympatric Amphibian Species KEVIN W. SAUNDERS. Dept of Biological Science, Marshall University, 1 John Marshall Drive, Huntington, WV, 25755 The purpose of this study was to collect data on the natural history of the Long-tailed Salamander (Eurycea l. longicauda) in eastern Kentucky and West Virginia. The objectives of this research included characterization of epigean and hypogean habitat for this species, recording distances moved by individuals in populations associated with caves, and collection of data on courtship, oviposition, and larval development. -

Appalachian Salamander Cons

PROCEEDINGS OF THE APPALACHIAN SALAMANDER CONSERVATION WORKSHOP - 30–31 MAY 2008 CONSERVATION & RESEARCH CENTER, SMITHSONIAN’S NATIONAL ZOOLOGICAL PARK, FRONT ROYAL, VIRGINIA, USA Hosted by Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, facilitated by the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group © Copyright 2008 CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Gratwicke, B (ed). 2008. Proceedings of the Appalachian Salamander Conservation Workshop. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. To order additional copies of Proceedings of the Appalachian Salamander Conservation Workshop, contact the CBSG office: [email protected], 001-952-997-9800, www.cbsg.org. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Salamanders, along with many other amphibian species have been declining in recent years. The IUCN lists 47% of the world’s salamanders threatened or endangered, yet few people know that the Appalachian region of the United States is home to 14% of the world’s 535 salamander species, making it an extraordinary salamander biodiversity hotspot, and a priority region for salamander conservation. -

Observations on the Population Ecology of the Cave Salamander, Eurycea Lucifuga (Rafinesque, 1822)

J. Gavin Bradley and Perri K. Eason. Observations on the population ecology of the cave salamander, eurycea lucifuga (rafinesque, 1822). Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, v. 81, no. 1, p. 1-8. DOI:10.4311/2017LS0037 OBSERVATIONS ON THE POPULATION ECOLOGY OF THE CAVE SALAMANDER, EURYCEA LUCIFUGA (RAFINESQUE, 1822) J. Gavin Bradley1 and Perri K. Eason2 Abstract Salamanders are potentially important constituents of subterranean ecosystems, but relatively little is known about their effects in caves. A common facultative hypogean salamander in the eastern United States is the Cave salamander, Eurycea lucifuga (Rafinesque, 1822). Despite being common and widespread, little more than basic information exists for this species. Herein, we provide new data concerning open population modeling, demographics, wet-biomass, and density estimation for a population in a small Kentucky spring cave. We have found population abundances of this spe- cies to be much higher than previously reported, and describe low capture probabilities and high survival probabilities. Average wet-weight per individual was 2.90 g, and estimated seasonal population wet-biomass peaked at 1426.8 g. Mean salamander density and wet-biomass density are 0.08 salamanders m2 and 0.22 g m2, respectively. The data we provide indicate that Cave salamanders have important ecological impacts on small spring cave systems. Introduction The Cave salamander, Eurycea lucifuga (Rafinesque, 1822), is a facultative cave dweller that is native to the east- ern United States (Hutchison, 1958; Williams, 1980; Petranka, 1998; Camp et al., 2014). The classification scheme of cave-dwelling organisms is in flux due to a lack of consensus for terminology that defines the gradations of dependency that organisms have on cave environments. -

Salamander News

Salamander News No. 12 December 2014 www.yearofthesalamander.org A Focus on Salamanders at the Toledo Zoo Article and photos by Timothy A. Herman, Toledo Zoo In the year 2000, the Toledo Zoo opened the award-winning “Frogtown, USA” exhibit, showcasing amphibians native to Ohio, including one display housing a variety of plethodontid salamanders. Captive husbandry of lungless salamanders of the family Plethodontidae had previously been extremely rudimentary, and few people had maintained these amphibians in zoos. In this exhibit in 2007, the first captive reproduction of the Northern Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) was achieved in a zoo setting, followed shortly thereafter by the Four-toed Salamander (Hemidactylium scutatum) A sample of the photogenic salamander diversity encountered during MUSHNAT/Toledo Zoo in an off-display holding fieldwork in Guatemala, clockwise from top left:Oedipina elongata, Bolitoglossa eremia, Bolitoglossa salvinii, Nyctanolis pernix. area. Inside: This exhibit was taken down and overhauled for Year of the Frog in page 2008, giving us the opportunity to design, from the ground up, a facility Year of the Salamander Partners 3 incorporating the lessons learned from the first iteration. Major components Ambystoma bishopi Husbandry 5 of this new Amazing Amphibians exhibit included a renovated plethodontid Western Clade Striped Newts 7 salamander display, holding space to develop techniques for the captive Giant Salamander Mesocosms 8 reproduction of plethodontid salamanders, and four biosecure rooms to 10 work with imperiled amphibians with the potential for release back into the Georgia Blind Salamanders wild. One of these rooms was constructed with the capacity to maintain Chopsticks for Salamanders 12 environmental conditions for high-elevation tropical salamanders. -

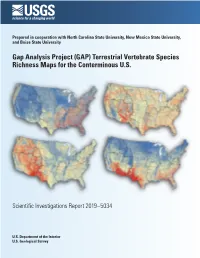

Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S

Prepared in cooperation with North Carolina State University, New Mexico State University, and Boise State University Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S. Scientific Investigations Report 2019–5034 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Mosaic of amphibian, bird, mammal, and reptile species richness maps derived from species’ habitat distribution models of the conterminous United States. Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S. By Kevin J. Gergely, Kenneth G. Boykin, Alexa J. McKerrow, Matthew J. Rubino, Nathan M. Tarr, and Steven G. Williams Prepared in cooperation with North Carolina State University, New Mexico State University, and Boise State University Scientific Investigations Report 2019–5034 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Year of the Salamander News No

Year of the Salamander News No. 1 January 2014 www.yearofthesalamander.org . State of the Plethodon cinereus Plethodon alamander Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (PARC) is celebrating 2014 as the Year of the Salamander to energize salamander education, research, and conservation. This is a worldwide effort, leveraged through the actions of numerous partner organizations and individuals from all walks of life – public to professional. Over the coming year, PARC and its collaborators will be working to raise awareness about: Eastern Red-backed Salamander, Eastern Red-backed Salamander, © Daniel Hocking • the importance of salamanders in natural systems and to humankind; • diverse ongoing research pathways aimed at better understanding salamanders, their role in ecosystems, and threats to their existence; Inside: page • actions being implemented around the world to conserve salamander Photo Contest & Calendar 2 populations and their habitats; Year of the Salamander Team 2 • education and outreach efforts through a kaleidoscope of individual and Salamander Myths 6 group involvement. Continued on p. 3 Logo Contest Winner 11 World Distribution of Salamanders (Order Caudata) Café Press PARCStore 11 State of the Salamander is available for download as a stand-alone document at www.yearofthesalamander.org Map © by TheEmirr/Maplab/Cypron Map Series, from Wikipedia sponsored by PARC - Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Year of the Salamander News No. 1, January 2014 2 Get Your January Photo Contest Calendar - Free! Long-tail on the march! Our January Year of the Salamander Photo Contest winner, Andrew Burmester, caught this Long- tailed Salamander (Eurycea longicauda longicauda) out and about in New Jersey. Download the January calendar to get the big picture and see the acrobatic runner-up at http://www. -

Analysis of Eurycea Hybrid Zone in Eastern Missouri

Scholars' Mine Masters Theses Student Theses and Dissertations Summer 2010 Analysis of Eurycea hybrid zone in eastern Missouri Bonnie Jean Beasley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses Part of the Biology Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Department: Recommended Citation Beasley, Bonnie Jean, "Analysis of Eurycea hybrid zone in eastern Missouri" (2010). Masters Theses. 6727. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses/6727 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 2 ANALYSIS OF EURYCEA HYBRID ZONE IN EASTERN MISSOURI by BONNIE JEAN BEASLEY A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the MISSOURI UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE IN APPLIED AND ENVIRONMENTAL BIOLOGY 2010 Approved by Anne Maglia, Advisor Melanie R. Mormile Jennifer Leopold 3 iii 4iii ABSTRACT Evolutionary mechanisms are often difficult to observe in action because evolution generally works slowly over time. Hybrid zones provide a unique opportunity to observe many evolutionary processes, such as reinforcement, because of the rapid changes that tend to occur in these zones. Salamanders provide an ideal model for examining the rapid changes in populations that result from hybridization because many closely-related species lack reproductive barriers. In Missouri, a well-documented hybridization zone exists among the two subspecies Eurycea longicauda longicauda (long-tailed salamander) and E. -

Ecology of the Eastern Long-Tailed Salamander (Eurycea

ECOLOGY OF THE EASTERN LONG-TAILED SALAMANDER (EURYCEA LONGICAUDA LONGICAUDA) ASSOCIATED WITH SPRINGHOUSES by Nathan H. Nazdrowicz A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Spring 2015 © 2015 Nathan H. Nazdrowicz All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number: 3718365 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 3718365 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 ECOLOGY OF THE EASTERN LONG-TAILED SALAMANDER (EURYCEA LONGICAUDA LONGICAUDA) ASSOCIATED WITH SPRINGHOUSES by Nathan H. Nazdrowicz Approved: __________________________________________________________ Jacob L. Bowman, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Approved: __________________________________________________________ Mark W. Rieger, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Approved: __________________________________________________________ James G. Richards, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

From a Cave Salamander, Eurycea Lucifuga and Grotto

93 First Report of Bothriocephalus rarus (Bothriocephalidea: Bothriocephalidae) from a Cave Salamander, Eurycea lucifuga and Grotto Salamanders, Eurycea spelaea (Caudata: Plethodontidae) from Oklahoma, with a Summary of Helminths from these Hosts Chris T. McAllister Science and Mathematics Division, Eastern Oklahoma State College, Idabel, OK 74745 Charles R. Bursey Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University-Shenango, Sharon, PA 16146 Henry W. Robison 9717 Wild Mountain Drive, Sherwood, AR 72120 Matthew B. Connior Life Sciences, Northwest Arkansas Community College, Bentonville, AR 72712 Stanley E. Trauth Department of Biological Sciences, Arkansas State University, State University, AR 72467 Danté B. Fenolio San Antonio Zoo, 3903 North St. Mary’s Street, San Antonio, TX 78212 ©2016 Oklahoma Academy of Science The cave salamander, Eurycea lucifuga species that occurs in darker zones of caves, Rafinesque, 1822, as its name implies, is underground streams and sinkholes in the Salem restricted to moist woodlands, cliff fissures, and and Springfield plateaus in the Ozark region of damp limestone caves in the Central Highlands southwestern Missouri to southeastern Kansas of North America from western Virginia and and adjacent areas from northern Arkansas to central Indiana southward to northern Georgia northeastern Oklahoma (Powell et al. 2016). and west to eastern Oklahoma (Powell et al. Larval grotto salamanders can be found outside 2016). In Oklahoma, E. lucifuga is restricted to of caves in surface springs and in the entrance karst systems in the northeastern portion of the zone of caves but can also be found living deeper state (Sievert and Sievert 2011). in cave systems (Fenolio et al. 2004; Trauth et al. -

The Population Ecology and Behavior of the Cave Salamander, Eurycea Lucifuga (Rafinesque, 1822)

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 The population ecology and behavior of the cave salamander, Eurycea lucifuga (Rafinesque, 1822). Joseph Gavin Bradley University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, Population Biology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Bradley, Joseph Gavin, "The population ecology and behavior of the cave salamander, Eurycea lucifuga (Rafinesque, 1822)." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3041. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3041 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POPULATION ECOLOGY AND BEHAVIOR OF THE CAVE SALAMANDER, EURYCEA LUCIFUGA (RAFINESQUE, 1822) By Joseph Gavin Bradley B.S., University of Louisville, 2011 M.S., University of Louisville, 2016 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology Department of Biology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2018 THE POPULATION ECOLOGY AND BEHAVIOR OF THE CAVE SALAMANDER, EURYCEA LUCIFUGA (RAFINESQUE, 1822) By J. Gavin Bradley B.S., University of Louisville, 2011 M.S., University of Louisville, 2016 A Dissertation Approved on July 3, 2018 by the following Dissertation Committee: Dissertation Director Perri Eason James Alexander Julian Lewis William Pearson Steve Yanoviak ii DEDICATION To Emma, Jameson, and Bailey iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, tremendously, Dr. -

Linking Husbandry and Behavior to Enhance Amphibian Reintroduction Success Luke Jack Linhoff [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 4-22-2018 Linking Husbandry and Behavior to Enhance Amphibian Reintroduction Success Luke Jack Linhoff [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006549 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Linhoff, Luke Jack, "Linking Husbandry and Behavior to Enhance Amphibian Reintroduction Success" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3688. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3688 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida LINKING HUSBANDRY AND BEHAVIOR TO ENHANCE AMPHIBIAN REINTRODUCTION SUCCESS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in BIOLOGY by Luke Jack Linhoff 2018 ! ! ! ! ! ! To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts, Sciences and Education This dissertation, written by Luke Jack Linhoff, and entitled Linking Husbandry and Behavior to Enhance Amphibian Reintroduction Success, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Joel Heinen _______________________________________ Steven Oberbauer _______________________________________ Joseph Mendelson _______________________________________ Yannis Papastamatiou _______________________________________ Maureen Donnelly, Major Professor Date of Defense: 22 March 2018 The dissertation of Luke Jack Linhoff is approved.