North Bengal and West Assam, India)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iconography of the Recently Discovered Naga Sculptures from Pamba River Basin, Pathanamthitta District, South Kerala

Iconography of the Recently Discovered Naga Sculptures from Pamba River Basin, Pathanamthitta District, South Kerala Ambily C.S.1, Ajit Kumar2 and Vinod Pancharath3 1. Excavation Branch II, Archaeological survey of India, Purana Qila, New Delhi – 110001, India (Email: [email protected]) 2. Department of Archaeology, University of Kerala, Kariavattom Campus, Thiruvananthapuram - 695581, Kerala, India (Email: [email protected]) 3. Industrial Design Centre, Indian Institute of Technology, Powai, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 25 September 2015; Accepted: 18 October 2015; Revised: 09 November 2015 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 3 (2015): 618-634 Abstract: Recent exploration by the first author brought to light interesting Naga sculptures from the middle ranges of Pamba River basin. All the sculptures are made out of granite and can be classified into Nagarajas and Nagayakshis except one which is a female naga devotee. This paper tries to briefly discuss the iconography, chronology and significance of the sculptures. Keywords: Exploration, Pamba River Basin, Kerala, Nagarajas, Nagayakshis, Iconography, Chronology Introduction Pamba is one of the important and third longest rivers in Kerala. It is apparently the river Baris/Bans mentioned in records of Pliny (Menon 1967-62). It originates from Pulachimalai hill in Peermade plateau at an altitude of 1650 MSL and has a length of 176km. It flows through Idukki, Pathanamthitta and Alappuzha districts and finally empties into the Vembanadu Lake. During medieval period Pamba basin harbored prosperous settlement like Kaviyur, Thiruvanmandoor, Perunnayil and Thiruvalla. Naga and yakshi images have earlier been reported from Niranam-Tiruvalla area (Mathew 2006). The present discoveries add to the list of known images. -

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

Hindu America

HINDU AMERICA Revealing the story of the romance of the Surya Vanshi Hindus and depicting the imprints of Hindu Culture on tho two Americas Flower in the crannied wall, I pluck you out of the crannies, I hold you here, root and all, in my hand. Little flower— but if I could understand What you arc. root and all. and all in all, I should know what God and man is — /'rimtjihui' •lis far m the deeps of history The Voice that speaVeth clear. — KiHtf *Wf. The IIV./-SM#/. CHAMAN LAL NEW BOOK CO HORNBY ROAD, BOMBAY COPY RIGHT 1940 By The Same Author— SECRETS OF JAPAN (Three Editions in English and Six translations). VANISHING EMPIRE BEHIND THE GUNS The Daughters of India Those Goddesses of Piety and Sweetness Whose Selflessness and Devotion Have Preserved Hindu Culture Through the Ages. "O Thou, thy race's joy and pride, Heroic mother, noblest guide. ( Fond prophetess of coming good, roused my timid mood.’’ How thou hast |! THANKS My cordial chaoks are due to the authors and the publisher* mentioned in the (eat for (he reproduction of important authorities from their books and loumils. My indchtcdih-ss to those scholars and archaeologists—American, European and Indian—whose works I have consulted and drawn freely from, ts immense. Bur for the results of list investigations made by them in their respective spheres, it would have been quite impossible for me to collect materials for this book. I feel it my duty to rhank the Republican Governments of Ireland and Mexico, as also two other Governments of Europe and Asia, who enabled me to travel without a passport, which was ruthlessly taken away from me in England and still rests in the archives of the British Foreign Office, as a punishment for publication of my book the "Vanishing Empire!" I am specially thankful to the President of the Republic of Mexico (than whom there is no greater democrat today)* and his Foreign Minister, Sgr. -

Shayesta Khan: 1.In the 17Th Century,Shayesta Khan Appointed As the Local Governor of Bengal

Class-4 BANGLADESH AND GLOBAL STUDIES ( Chapter 14- Our History ) Topic- 2“ The Middle Age” Lecture - 3 Day-3 Date-27/9/20 *** 1st read the main book properly. Middle Ages:The Middle Age or the Medieval period was a period of European history between the fall of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Renaissance. Discuss about three kings of the Middle age: Shamsuddin Ilias Shah: 1.He came to power in the 14th century. 2.His main achievement was to keep Bengal independent from the sultans of Delhi. 3.Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah opened up Shahi dynasty. Isa Khan: 1.Isa Khan was the leader of the landowners in Bengal, called the Baro Bhuiyan. 2.He was the landlord of Sonargaon. 3.In the 16th century, he fought for independence of Bengal against Mughal emperor Akhbar. Shayesta Khan: 1.In the 17th century,Shayesta Khan appointed as the local governor of Bengal. 2.At his time rice was sold cheap.One could get one mound of rice for eight taka only. 3.He drove away the pirates from his region. The social life in the Middle age: 1.At that time Bengal was known for the harmony between Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims. 2.It was also known for its Bengali language and literature. 3.Clothes and diets of Middle age wren the same as Ancient age. The economic life in the Middle age: 1.Their economy was based on agriculture. 2.Cotton and silk garments were also renowned as well as wood and ivory work. 3.Exports exceeded imports with Bengal trading in garments, spices and precious stones from Chattagram. -

Annual Report 2013

SRI VENKATESWARA SWAMY TEMPLE OF COLORADO 1495 S Ridge Road, Castle Rock, CO 80104 Annual Report 2013 Sri Padmavati Devi Dear founding members, Welcome to the 2013 Annual General Body Meeting of SVTC. We, the members of the Board of Trustees of SVTC express our deep sense of gratitude and appreciation recognizing your infinite unending degree of service in many forms and shape including but not limited to your precious time, efforts in many ways in addition to an important facet of monetary contribution and support. We would like to enumerate some of the significant, noteworthy accomplishments and activities during the past year, in addition to presenting important financial information, facts related to SVTC land and resolution. Construction: It has been a major and great accomplishment to be able to start and complete the Sanctum Sanctorum (Gharbha Gudi) of Sri Venkateswara Swamy, Sri Padmavati Ammavaru and Sri Godadevi (Andal) in addition to other shrines of Sri Sathyanarayana Swamy, Sri Sudharshana and Sri Narasimha Swamy, Sri Vishvaksena, Sri Jaya, Sri Vijaya, Sri Garuda, Sri Vighneswara Swamy, Sri Shiva and Parvathi, Sri Subrahmanya Swamy and Sri Ramanuja Swamy. Construction of all of the Gopurams has been accomplished. The initial phase of Indianization has been completed. Construction of Dwajasthambam was completed in spite of significant technological, religious and structural issues to be taken into consideration. Upgraded and remodeled our coat and shoe storing facility. We would like to mention here very briefly the major events of Dwajasthamba Pratishtha, Maha Kumbhabhishekam and Prana Prathishta followed by Mandalabhishekam, the details can be viewed in the other section of the report. -

Shri Sai Sat Charitra By

Shri Sai Sat Charitra By Govind Raghunath Dabholkar alias ‘Hemadpant Chapter I ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter II ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Chapter III ......................................................................................................................................................11 Chapter IV......................................................................................................................................................15 Chapter V.......................................................................................................................................................20 Chapter VI......................................................................................................................................................26 Chapter VII.....................................................................................................................................................32 Chapter VIII....................................................................................................................................................38 Chapter IX......................................................................................................................................................42 Chapter X.......................................................................................................................................................47 -

Download Download

ACTA ORIENTALIA EDIDERUNT SOCIETATES ORIENTALES DANICA FENNICA NORVEGIA SVECIA CURANTIBUS LEIF LITTRUP, HAVNIÆ HEIKKI PALVA, HELSINGIÆ ASKO PARPOLA, HELSINGIÆ TORBJÖRN LODÉN, HOLMIÆ SIEGFRIED LIENHARD, HOLMIÆ SAPHINAZ AMAL NAGUIB, OSLO PER KVÆRNE, OSLO WOLFGANG-E. SCHARLIPP, HAVNIÆ REDIGENDA CURAVIT CLAUS PETER ZOLLER LXXVIII Contents ARTICLES CLAUS PETER ZOLLER: Traditions of transgressive sacrality (against blasphemy) in Hinduism ......................................................... 1 STEFAN BOJOWALD: Zu den Wortspielen mit ägyptisch „ib“ „Herz“ ................................ 163 MAHESHWAR P. JOSHI: The hemp cultivators of Uttarakhand and social complexity (with a special reference to the Rathis of Garhwal) ........................................................................................... 173 MICHAEL KNÜPPEL: Überlegungen zu den Verwandtschaftsverhältnissen der Jenissej- Sprachen bei Georg Heinrich August Ewald.................................... 223 DR DEEPAK JOHN MATHEW AND PARTHIBAN RAJUKALIDOSS: Architecture and Living Traditions Reflected in Wooden Rafters of Śrīvilliputtūr Temple ........................................................................ 229 BOOK REVIEWS B. J. J. HARING/O. E. KAPER/R. VAN WALSEM (EDS.). The Workman´s Progress, Studies in the Village of Deir el-Medina and other documents from Western Thebes in Honour of Rob Demarée, reviewed by Stefan Bojowald........................................................... 267 Acta Orientalia 2017: 78, 1–162. Copyright © 2017 Printed in India – all rights -

Get Set Go Travels Hotel Akshaya Building, Opp: DRM Office, Waltair Station Approach Road, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh 530016

Get Set Go Travels Hotel Akshaya Building, Opp: DRM Office, Waltair Station Approach Road, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh 530016. Phone: +91 92468 14399, +91 90004 18895 Mail: [email protected] Web: www.getsetgotravels.in The Pancharama Kshetras or the (Pancharamas) are five ancient Hindu temples of Lord Shiva situated in Andhra Pradesh. These Sivalingas are formed out of one single Sivalinga. As per the legend, this five Sivalingas were one which was owned by the Rakshasa King Tarakasura. None could win over him due to the power of this Sivalinga. In a war between deities and Tarakasura, Kumara Swamy and Tarakasura were face to face. Kumara Swamy used his Sakthi aayudha to kíll Taraka. By the power of Sakti aayudha the body of Taraka was torn into pieces. But to the astonishment of Lord Kumara Swamy all the pieces reunited to give rise to Taraka. Kumara Swamy repeatedly broke the body into pieces and it was re-unified again and again. This confused Lord Kumara Swamy and was in an embarrassed state then Lord Sriman-Narayana appeared before him and said “Kumara! Don’t get depressed, without breaking the Shiva lingham worn by the asura you can’t kíll him” you should first break the Shiva lingam into pieces, then only you can kíll Taraka Lord Vishnu also said that after breaking, the shiva lingha it will try to unite. To prevent the Linga from uniting, all the pieces should be fixed in the place where they are fallen by worshiping them and erecting temples on them. By taking the word of Lord Vishnu, Lord Kumara Swamy used his Aagneasthra (weapon of fire) to break the Shiva lingha worn by Taraka, Once the Shiva lingha broke into five pieces and was trying to unite by making Omkara nada (Chanting Om). -

India Architecture Guide 2017

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Zanskar Geologically, the Zanskar Range is part of the Tethys Himalaya, an approximately 100-km-wide synclinorium. Buddhism regained its influence Lungnak Valley over Zanskar in the 8th century when Tibet was also converted to this ***** Zanskar Desert ཟངས་དཀར་ religion. Between the 10th and 11th centuries, two Royal Houses were founded in Zanskar, and the monasteries of Karsha and Phugtal were built. Don't miss the Phugtal Monastery in south-east Zanskar. Zone 2: Punjab Built in 1577 as the holiest Gurdwara of Sikhism. The fifth Sikh Guru, Golden Temple Rd, Guru Arjan, designed the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) to be built in Atta Mandi, Katra the centre of this holy tank. The construction of Harmandir Sahib was intended to build a place of worship for men and women from all walks *** Golden Temple Guru Ram Das Ahluwalia, Amritsar, Punjab 143006, India of life and all religions to come and worship God equally. The four entrances (representing the four directions) to get into the Harmandir ਹਰਿਮੰਦਿ ਸਾਰਹਬ Sahib also symbolise the openness of the Sikhs towards all people and religions. Mon-Sun (3-22) Near Qila Built in 2011 as a museum of Sikhism, a monotheistic religion originated Anandgarh Sahib, in the Punjab region. Sikhism emphasizes simran (meditation on the Sri Dasmesh words of the Guru Granth Sahib), that can be expressed musically *** Virasat-e-Khalsa Moshe Safdie Academy Road through kirtan or internally through Nam Japo (repeat God's name) as ਰਿਿਾਸਤ-ਏ-ਖਾਲਸਾ a means to feel God's presence. -

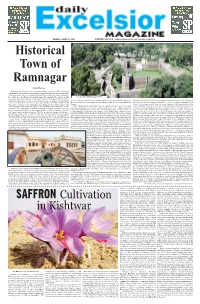

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 2)

SUNDAY, JUNE 27, 2021 INTERNET EDITION : www.dailyexcelsior.com/sunday-magazine Historical Town of Ramnagar Ashok Sharma Ramnagar is a historical town located at a distance of about 38 Kms to the west of Udhampur. It is named after its last ruler, King Ram Singh who was ousted by the Sikh forces in 1822 AD. It is a beautiful town divided into thirteen wards and has got the status of a sub division functioning under the administrative control of Sub A top view of Ramnagar Fort. Divisional Magistrate. It has also a municipal Committee to look after the civic affairs of the town and a Degree College located at a scenic and serene place on the outskirts other in opposite wings.The outer walls are high and are supported by buttresses. felt and a site was selected which was a ridge situated at a distance of about 800 mts of the town, spread over an area of about 300 Kanals of land. The Campus of the The rooms have wooden ceilings and the interior walls are decorated with floral from the old palace.It is square in structure 42.65 x 42.65 mts in measurement. It University of Jammu is also functioning here. Ramnagar was earlier ruled by the designs. boasts of a masonary work of huge cut stones mortared with lime powder and the Bandral Rajputs and it was the capital of the erstwhile state of Bandralta. It was Shesh Mahal was built during the reign of Raja Ram Singh in 1885.It is a royal paste of legumes.There are four corners of the fort which make the four turrets con- founded by the royal family of Chamba belonging to Chambyal Dynasty. -

Translations of Bhupen Hazarika Songs Translator Bios

Translations of Bhupen Hazarika Songs them. They would often ask me to translate into English so that they would understand the words better. That’s how I got into translating poems - and in Bhupen Hazarika (Assamese: ভূ পেন হাজৰিকা) (1926–2011) was an Indian lyricist, collaboration with my daughters and wife. It gives me sheer joy, particularly musician, singer, poet and film-maker from Assam. His songs, written and sung when I can translate with my daughters who love Bengali culture. They do not mainly in the Assamese language by himself, are marked by humanity and gloss over but take keen interest in conveying the nuances. universal brotherhood and have been translated and sung in many languages, most notably in Bengali and Hindi. He is also acknowledged to have introduced Pampi the culture and folk music of Assam and Northeast India to Hindi cinema at the I’m a digital mixed media performance artist and poet. I’m my father’s national level. daughter. Translating Bengali with my father is an exercise in remembering sweet sounds that swell me up and a challenge to see how much I’ve retained For a brief period he worked at All India Radio, Guwahati when he won a after almost three decades of living in the States – not to mention something scholarship from Columbia University and set sail for New York in 1949. There fun and frustrating to do with my old man. How much of it I still understand! he earned a PhD (1952) on his thesis "Proposals for Preparing India's Basic Education to use Audio-Visual Techniques in Adult Education". -

Dimasa Kachari of Assam

ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY NO·7II , I \ I , CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME I MONOGRAPH SERIES PART V-B DIMASA KACHARI OF ASSAM , I' Investigation and Draft : Dr. p. D. Sharma Guidance : A. M. Kurup Editing : Dr. B. K. Roy Burman Deputy Registrar General, India OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS NEW DELHI CONTENTS FOREWORD v PREFACE vii-viii I. Origin and History 1-3 II. Distribution and Population Trend 4 III. Physical Characteristics 5-6 IV. Family, Clan, Kinship and Other Analogous Divisions 7-8 V. Dwelling, Dress, Food, Ornaments and Other Material Objects distinctive qfthe Community 9-II VI. Environmental Sanitation, Hygienic Habits, Disease and Treatment 1~ VII. Language and Literacy 13 VIII. Economic Life 14-16 IX. Life Cycle 17-20 X. Religion . • 21-22 XI. Leisure, Recreation and Child Play 23 XII. Relation among different segments of the community 24 XIII. Inter-Community Relationship . 2S XIV Structure of Soci141 Control. Prestige and Leadership " 26 XV. Social Reform and Welfare 27 Bibliography 28 Appendix 29-30 Annexure 31-34 FOREWORD : fhe Constitution lays down that "the State shall promote with special care the- educational and economic hterest of the weaker sections of the people and in particular of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation". To assist States in fulfilling their responsibility in this regard, the 1961 Census provided a series of special tabulations of the social and economic data on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are notified by the President under the Constitution and the Parliament is empowered to include in or exclude from the lists, any caste or tribe.