Kargil Conflict View from Kashmir K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compte Rendu De: Ladakhi Histories

Compte rendu de : Ladakhi Histories: Local and regional perspectives Pascale Dollfus To cite this version: Pascale Dollfus. Compte rendu de : Ladakhi Histories: Local and regional perspectives . 2006, pp.172- 177. halshs-01694592 HAL Id: halshs-01694592 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01694592 Submitted on 2 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 172 EBHR 29-30 Ladakhi Histories: Local and regional perspectives, edited by John Bray. Leiden: Brill (Tibetan Studies Library, 9). 2005. x + 406 pages, 36 maps, figures and plates, index. ISBN 90 04 14551 6. Reviewed by Pascale Dollfus, Paris. This volume illustrates the plurality of approaches to studying history and current research in the making. It compiles contributions – very different in length and in style – from researchers from a variety of disciplines: linguistics, tibetology, anthropology, history, art and archaeology. Their sources include linguistics, archaeological and artistical evidence; Tibetan chronicles, Persian biographies and European travel accounts; government records and private correspondence, land titles and trade receipts; oral tradition and reminiscence of survivors' recollections. The majority of the papers were first presented at the International Association of Ladakh Studies (IALS) conferences held in 1999, 2001 and 2003, and these have been supplemented by a few additional contributions. -

Conflict Transformation in Kashmir-III

Journal of Peace Studies, Vol. 12, Issue 4, October-December 2005 Conflict Transformation in Kashmir-III Riyaz Punjabi* [*Professor Riyaz Punjabi is President (Hony.), International Centre for Peace Studies, New Delhi. He teaches in the Centre for the Study of Social Systems, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India.] In the last two parts of this ongoing study, an attempt was made to look inward to locate the roots of the conflict within the J&K state. The study also looked at the political developments which laid an impact on the stateÊs relations with the Union of India. However, the conflict in Kashmir has external linkages too. The present analysis shall deal with the external aspect of the conflict in Kashmir. Backdrop Pakistan has been claiming Kashmir on the basis of ÂTwo NationÊ theory in which the sub-continent was divided on religious lines and the State of Pakistan was created. The Pakistani scholars claim that gradually Kashmir got intertwined in the strategic and defense doctrine of Pakistan. However, this approach ignores the legal arrangements which were evolved to demarcate the boundaries between India and Pakistan as a consequence of the accord to divide the sub-continent on religious lines. That a formula was also devised for the Princely states which were not under the direct control of British government to accede to the either dominion is not taken into cognisance. This approach equally ignores the political developments in J&K state between1940 when Pakistan resolution was adopted by the Muslim League and the 1947 when Pakistan was actually created. It may be mentioned here that Kashmir was not a party to the ÂTwo NationÊ theory advocated by Muslim League. -

Distribution of Bufotes Latastii (Boulenger, 1882), Endemic to the Western Himalaya

Alytes, 2018, 36 (1–4): 314–327. Distribution of Bufotes latastii (Boulenger, 1882), endemic to the Western Himalaya 1* 1 2,3 4 Spartak N. LITVINCHUK , Dmitriy V. SKORINOV , Glib O. MAZEPA & LeO J. BORKIN 1Institute Of Cytology, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Tikhoretsky pr. 4, St. Petersburg 194064, Russia. 2Department of Ecology and EvolutiOn, University of LauSanne, BiOphOre Building, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland. 3 Department Of EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy, EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy Centre (EBC), Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. 4ZoOlOgical Institute, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 1, St. PeterSburg 199034, Russia. * CorreSpOnding author <[email protected]>. The distribution of Bufotes latastii, a diploid green toad species, is analyzed based on field observations and literature data. 74 localities are known, although 7 ones should be confirmed. The range of B. latastii is confined to northern Pakistan, Kashmir Valley and western Ladakh in India. All records of “green toads” (“Bufo viridis”) beyond this region belong to other species, both to green toads of the genus Bufotes or to toads of the genus Duttaphrynus. B. latastii is endemic to the Western Himalaya. Its allopatric range lies between those of bisexual triploid green toads in the west and in the east. B. latastii was found at altitudes from 780 to 3200 m above sea level. Environmental niche modelling was applied to predict the potential distribution range of the species. Altitude was the variable with the highest percent contribution for the explanation of the species distribution (36 %). urn:lSid:zOobank.Org:pub:0C76EE11-5D11-4FAB-9FA9-918959833BA5 INTRODUCTION Bufotes latastii (fig. 1) iS a relatively cOmmOn green toad species which spreads in KaShmir Valley, Ladakh and adjacent regiOnS Of nOrthern India and PakiStan. -

Current Affairs October 2020

Current Affairs 2020 Current Affairs October 2020 International Day of Rural Women 2020 International Day of Rural Women is celebrated on 15 October. From agriculture to food security, nutrition, land and natural resource management, domestic care and work, rural women are at the forefront and are taking charge by being in the driver's seat. The International Day of Rural Women was created in 1995 by Civil society organizations at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing and was declared an official UN Day in 2007 by the UN General Assembly. From agriculture to food security, nutrition, land and natural resource management, domestic care and work, rural women are at the forefront. The theme for this International Day of Rural Women is “Building rural women’s resilience in the wake of COVID-19,” to create awareness of these women’s struggles, their needs, and their critical and key role in our society. Cabinet approved Special Package for UT of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh Union Cabinet has approved a Special Package worth Rs. 520 crore in the UTs of J&K and Ladakh for a period of five years till FY 2023-24 and ensure funding of DeendayalAntyodaya Yojana - National Rural Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NRLM) in the UTs of Jammu and Kashmir & Ladakh on a demand driven basis without linking allocation with poverty ratio during this extended period. This will ensure sufficient funds under the Mission, as per need to the UTs and is also in line with Government of India's aim to universalize all centrally sponsored beneficiary-oriented schemes in the UTs of J&K and Ladakh in a time bound manner. -

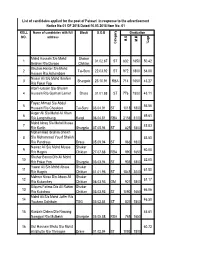

1 Mohd Hussain S/O Mohd Ibrahim R/O Dargoo Shakar Chiktan 01.02

List of candidates applied for the post of Patwari in response to the advertisement Notice No:01 OF 2018 Dated:10.03.2018 Item No: 01 ROLL Name of candidates with full Block D.O.B Graduation NO. address M.O M.M %age Category Category Mohd Hussain S/o Mohd Shakar 1 01.02.87 ST 832 1650 50.42 Ibrahim R/o Dargoo Chiktan Ghulam Haider S/o Mohd 2 Tai-Suru 22.03.92 ST 972 1800 54.00 Hassan R/o Achambore Nissar Ali S/o Mohd Ibrahim 3 Shargole 23.10.91 RBA 714 1650 43.27 R/o Fokar Foo Altaf Hussain S/o Ghulam 4 Hussain R/o Goshan Lamar Drass 01.01.88 ST 776 1800 43.11 Fayaz Ahmad S/o Abdul 5 56.56 Hussain R/o Choskore Tai-Suru 03.04.91 ST 1018 1800 Asger Ali S/o Mohd Ali Khan 6 69.61 R/o Longmithang Kargil 06.04.81 RBA 2158 3100 Mohd Ishaq S/o Mohd Mussa 7 45.83 R/o Karith Shargole 07.05.94 ST 825 1800 Mohammad Ibrahim Sheikh 8 S/o Mohammad Yousf Sheikh 53.50 R/o Pandrass Drass 05.09.94 ST 963 1800 Nawaz Ali S/o Mohd Mussa Shakar 9 60.00 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 27.07.88 RBA 990 1650 Shahar Banoo D/o Ali Mohd 10 52.00 R/o Fokar Foo Shargole 03.03.94 ST 936 1800 Yawar Ali S/o Mohd Abass Shakar 11 61.50 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 01.01.96 ST 1845 3000 Mehrun Nissa D/o Abass Ali Shakar 12 51.17 R/o Kukarchey Chiktan 06.03.93 OM 921 1800 Bilques Fatima D/o Ali Rahim Shakar 13 66.06 R/o Kukshow Chiktan 03.03.93 ST 1090 1650 Mohd Ali S/o Mohd Jaffer R/o 14 46.50 Youkma Saliskote TSG 03.02.84 ST 837 1800 15 Kunzais Dolma D/o Nawang 46.61 Namgyal R/o Mulbekh Shargole 05.05.88 RBA 769 1650 16 Gul Hasnain Bhuto S/o Mohd 60.72 Ali Bhutto R/o Throngos Drass 01.02.94 ST -

Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %Age 1 1898155 MOHD BAQIR MOHAMMED ALI FAROONA P-O SALISKOTE

Selection List of candidates who have applied for admission to B. Ed Programme (Kargil Chapter) offered through Directorate of Admisssions, University of Kashmir session-2018 Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %age OM 1 1898155 MOHD BAQIR MOHAMMED ALI FAROONA P-O SALISKOTE, KARGIL KARGIL ST 9 7.09 78.78 2 1898735 SHAHAR BANOO MOHAMMAD BAQIR BAROO KARGIL KARGIL ST 10 7.87 78.70 3 1895262 FARIDA BANOO MOHD HUSSAIN SHAKAR KARGIL ST 2400 1800 75.00 VILLAGE PASHKUM DISTRICT KARGIL, 4 1897102 HABIBULLAH MOHD BAQIR LADAKH. KARGIL ST 3000 2240 74.67 5 1894751 ANAYAT ALI MOHD SOLEH STICKCHEY CHOSKORE KARGIL ST 2400 1776 74.00 6 1898483 STANZIN SALTON TASHI SONAM R/O MULBEK TEHSIL SHARGOLE KARGIL ST 3000 2177 72.57 7 1892415 IZHAR HUSSAIN NIYAZ ALI TITICHUMIK BAROO POST OFFICE BAROO KARGIL ST 3600 2590 71.94 8 1897301 MOHD HASSAN HADIRE MOHD IBRAHIM HARDASS GRONJUK THANG KARGIL KARGIL ST 3100 2202 71.03 9 1896791 MOHD HUSSAIN GHULAM MOHD ACHAMBORE TAISURU KARGIL KARGIL ST 4000 2835 70.88 10 1898160 MOHD HUSSAIN MOHD TOHA KHANGRAL,CHIKTAN,KARGIL KARGIL ST 3400 2394 70.41 11 1898257 MARZIA BANOO MOHD ALI R/O SAMRAH CHIKTAN KARGIL KARGIL ST 10 7 70.00 12 1893813 ZAIBA BANOO KACHO TURAB SHAH YABGO GOMA KARGIL KARGIL ST 2100 1466 69.81 13 1894898 MEHMOOD MOHD ALI LANKERCHEY KARGIL ST 4000 2784 69.60 14 1894959 SAJAD HUSSAIN MOHD HASSAN ACHAMBORE TAISURU KARGIL ST 3000 2071 69.03 15 1897813 IMRAN KHAN AHMAD KHAN CHOWKIAL DRASS KARGIL RBA 4650 3202 68.86 16 1897210 ARCHO HAKIMA SYED ALI SALISKOTE TSG KARGIL ST 500 340 68.00 17 -

The “Anti-Nationals” RIGHTS Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India WATCH

India HUMAN The “Anti-Nationals” RIGHTS Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India WATCH The “Anti-Nationals” Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-735-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org February 2011 ISBN 1-56432-735-3 The “Anti-Nationals” Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India Map of India ............................................................................................................. 1 Summary ................................................................................................................. 2 Recommendations for Immediate Action by the Indian Government .................. 10 Methodology ......................................................................................................... 12 I. Recent Attacks Attributed to Islamist and Hindu Militant Groups ....................... -

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 “STATISTICAL HANDBOOK” DISTRICT KARGIL UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 RELEASED BY: DISTRICT STATISTICAL & EVALUATION OFFICE KARGIL D.C OFFICE COMPLEX BAROO KARGIL J&K. TELE/FAX: 01985-233973 E-MAIL: [email protected] Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH, Chairman/ Chief Executive Councilor, LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985 233827, 233856 Message It gives me immense pleasure to know that District Statistics & Evaluation Agency Kargil is coming up with the latest issue of its ideal publication “Statistical Handbook 2018-19”. The publication is of paramount importance as it contains valuable statistical profile of different sectors of the district. I hope this Hand book will be useful to Administrators, Research Scholars, Statisticians and Socio-Economic planners who are in need of different statistics relating to Kargil District. I appreciate the efforts put in by the District Statistics & Evaluation Officer and the associated team of officers and officials in bringing out this excellent broad based publication which is getting a claim from different quarters and user agencies. Sd/= (Feroz Ahmed Khan ) Chairman/Chief Executive Councilor LAHDC, Kargil Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH District Magistrate, (Deputy Commissioner/CEO) LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985-232216, Tele Fax: 232644 Message I am glad to know that the district Statistics and Evaluation Office Kargil is releasing its latest annual publication “Statistical Handbook” for the year 2018- 19. The present publication contains statistics related to infrastructure as well as Socio Economic development of Kargil District. -

Kargil Operation 1999

KARGIL OPERATION 1999 The Kargil War, also known as the Kargil conflict was an armed conflict between India and Pakistan that took place between May and July 1999 in the Kargil district of Kashmir and elsewhere along the Line of Control (LOC). In India, the conflict is also referred to as Operation Vijay which was the name of the Indian operation to clear the Kargil sector.The war is the most recent example of high-altitude warfare in mountainous terrain, and as such posed significant logistical problems for the combating sides.The cause of the war was the infiltration of Pakistani soldiers disguised as Kashmiri militants into positions on the Indian side of the LOC which serves as the border between the two states. During the initial stages of the war, Pakistan blamed the fighting entirely on independent Kashmiri insurgents, but documents left behind by casualties and later statements by Pakistan's Prime Minister and Chief of Army Staff showed involvement of Pakistani paramilitary forces led by General Ashraf Rashid. The Indian Army, later supported by the Indian Air Force, recaptured a majority of the positions on the Indian side of the LOC infiltrated by the Pakistani troops and militants. Facing international diplomatic opposition, the Pakistani forces withdrew from the remaining Indian positions along the LOC. There were three major phases to the Kargil War. First, Pakistan infiltrated forces into the Indian-controlled section of Kashmir and occupied strategic locations enabling it to bring NH1 within range of its artillery fire. The next stage consisted of India discovering the infiltration and mobilising forces to respond to it. -

Colour October 10

REKHA CHOWDHARY KASHMIR ISSUE RAKESH ANKIT Gender and Conflict Whose was Look Back, Look Farward Situation in Kashmir Kashmir to be ? By Talib Malik EpilogueJ & K ’ S M O N T H LY M A G A Z I N E ISSN : 0974-5653 N E W S , C U R R E N T A F F A I R S , S O C I A L S C I E N C E S SILVER LINING IN DARK CLOUDS T W O Y E A R S O F CROSS LoC TRADE REFLECTIONS ON KASHMIR SITUATION N N Vohra, Prof Saifuddin Soz Governor, J&K President Congress Party J&k Unit Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, Muzaffar Baig, Chairman APHC-M Senior PDP Leader M Y Tarigami, Bilal Lone, MLA, Secretary J&k State Committee, CPI-M Chairman J&K People's Conference Taj Mohi-ud-din Bashir Manzar Minister Public Health Engg., Irri. & Flood Control, Editor Kashmir Images, Srinagar Rigzin Jora, Hashim Qureshi Minister of Tourism & Culture Chairman J&K Democratic Liberation Party Nasir Hussain Munshi, Prof. Abdul Ghani Bhatt, Councillor LAHDC-K Chairman Muslim Conference Tsewang Rigzin, Aak Kacho, Associate Editor Epilogue Chief Executive Councillor LAHDC-Kargil Lobzang Rinchen, Thupstan Chhewang, 2010 / Vol 4 Issue 10 || Price Rs. 30 Postal Regd. No. JK-350/2009-11 www.epilogue.in , President Ladakh Buddhist Association Senior Leader LUTF, Former MP Phunstog Namgyal, Rigzin Spalbar, Congress Leader, Former Union Minister Former Chairman & CEO LAHDC Tsering Dorje, Mohammad Shafi Lassu, October 1 LUTF Chairman & CEO LAHDC Anjumian Moin-ul-Islam, Leh , Contributed by Belgian Association for Solidarity with J&K Jammu 1 Epilogue because there is more to know www.epilogue.in C O N T E N T Editor Prologue 2 Zafar Iqbal Choudhary Contributors to this Issue 3 Publisher SILVER LINING Kashmir Look Back, Look Ahead 5 Yogesh Pandoh Talib Malik I N D A R K C L O U D S Another questions to ponder over 7 Consulting Editor in Kashmir D. -

Ladakh Studies

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES _ 19, March 2005 CONTENTS Page: Editorial 2 News from the Association: From the Hon. Sec. 3 Nicky Grist - In Appreciation John Bray 4 Call for Papers: 12th Colloquium at Kargil 9 News from Ladakh, including: Morup Namgyal wins Padmashree Thupstan Chhewang wins Ladakh Lok Sabha seat Composite development planned for Kargil News from Members 37 Articles: The Ambassador-Teacher: Reflections on Kushok Bakula Rinpoche's Importance in the Revival of Buddhism in Mongolia Sue Byrne 38 Watershed Development in Central Zangskar Seb Mankelow 49 Book reviews: A Checklist on Medicinal & Aromatic Plants of Trans-Himalayan Cold Desert (Ladakh & Lahaul-Spiti), by Chaurasia & Gurmet Laurent Pordié 58 The Issa Tale That Will Not Die: Nicholas Notovitch and his Fraudulent Gospel, by H. Louis Fader John Bray 59 Trance, Besessenheit und Amnesie bei den Schamanen der Changpa- Nomaden im Ladakhischen Changthang, by Ina Rösing Patrick Kaplanian 62 Thesis reviews 63 New books 66 Bray’s Bibliography Update no. 14 68 Notes on Contributors 72 Production: Bristol University Print Services. Support: Dept of Anthropology and Ethnography, University of Aarhus. 1 EDITORIAL I should begin by apologizing for the fact that this issue of Ladakh Studies, once again, has been much delayed. In light of this, we have decided to extend current subscriptions. Details are given elsewhere in this issue. Most recently we postponed publication, because we wanted to be able to announce the place and exact dates for the upcoming 12th Colloquium of the IALS. We are very happy and grateful that our members in Kargil will host the colloquium from July 12 through 15, 2005. -

The First National Conference Government in Jammu and Kashmir, 1948-53

THE FIRST NATIONAL CONFERENCE GOVERNMENT IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR, 1948-53 THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN HISTORY BY SAFEER AHMAD BHAT Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ISHRAT ALAM CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2019 CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION I, Safeer Ahmad Bhat, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, certify that the work embodied in this Ph.D. thesis is my own bonafide work carried out by me under the supervision of Prof. Ishrat Alam at Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. The matter embodied in this Ph.D. thesis has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. I declare that I have faithfully acknowledged, given credit to and referred to the researchers wherever their works have been cited in the text and the body of the thesis. I further certify that I have not willfully lifted up some other’s work, para, text, data, result, etc. reported in the journals, books, magazines, reports, dissertations, theses, etc., or available at web-sites and included them in this Ph.D. thesis and cited as my own work. The manuscript has been subjected to plagiarism check by Urkund software. Date: ………………… (Signature of the candidate) (Name of the candidate) Certificate from the Supervisor Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University This is to certify that the above statement made by the candidate is correct to the best of my knowledge. Prof. Ishrat Alam Professor, CAS, Department of History, AMU (Signature of the Chairman of the Department with seal) COURSE/COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION/PRE- SUBMISSION SEMINAR COMPLETION CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr.