California Central Valley Steelhead Distinct Population Segment Factsheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Saltiest Springs in the Sierra Nevada, California

The Saltiest Springs in the Sierra Nevada, California Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5053 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Photograph of more than a dozen salt-evaporation basins at Hams salt spring, which have been carved by Native Americans in granitic bedrock. Saline water flows in light-colored streambed on left. Photograph by J.S. Moore, 2009. The Saltiest Springs in the Sierra Nevada, California By James G. Moore, Michael F. Diggles, William C. Evans, and Karin Klemic Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5053 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William H. Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Moore, J.G., Diggles, M.F., Evans, W.C., and Klemic, K., 2017, The saltiest springs in the Sierra Nevada, California: U.S. -

Smith, J.R. Et Al., 2007. Acoustic Monitoring of Mokelumne River

•3 Two hatchery smolts moved upstream Acoustic Monitoring of from the release site into the Cosumnes River. They held there for >30 days and then moved up the Sacramento River Mokelumne River •4 Oncorhynchus mykiss PRELIMINARY RESULTS James R. Smith1 , Michelle L. Workman1, 2 3 • All hatchery smolts were detected at least once by the receiver grid. Time from release to last detection ranged from 1 to 114 Joseph E. Merz , Walter Heady , and days 1 • All hatchery reconditioned kelts were detected. Time ranged from 1 to 81 days. Joseph J. Miyamoto • Forty-Seven of sixty-four (73%) of wild O. mykiss were detected by combined stationary and mobile tracking techniques. • Time from release to last detection ranged from 1-136 days for stationary receivers and from 5 to 173 days for 1 East Bay Municipal Utility District, 1 Winemasters Way, Lodi, CA 95240 mobile tracking. 2 Cramer Fish Sciences, 636 Hedburg Way #22, Oakdale, CA 95361 3 University of California, Santa Cruz, Long Marine Lab, 100 Shaffer Rd., Santa Cruz, CA 95060 70% 60% Project funded by the California Urban Water Agencies 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Percent of Release Group Vicinity of Mokelumne Sacramento Delta/Bay None INTRODUCTION Release River River The Mokelumne River Fish Hatchery (Hatchery) has released over 2 million smolt Detections through 7/13/2007 steelhead, Oncorhyncus mykiss, in the lower Mokelumne River since 1995, however, fewer than 750 adults have returned to the Hatchery since 1996. There have been limited data Hatchery Smolts n=57 Reconditioned Kelts n=7 Wild Caught Various n=64 Detections occurred in four major categories: 1)detections in vicinity of release site; collected on the movements of these fish once released. -

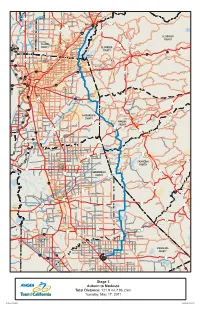

Spring Gap-Stanislaus Project Is Located in Calaveras and Tuolumne Counties, CA on the Middle Fork Stanislaus River (Middle Fork) and South Fork Stanislaus River

Hydropower Project License Summary STANISLAUS RIVER, CALIFORNIA SPRING GAP-STANISLAUS HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT (P-2130) Photo Credit: California State Water Board This summary was produced by the Hydropower Reform Coalition Stanislaus River, CA STANISLAUS RIVER, CA SPRING GAP-STANISLAUS HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT (P-2130) DESCRIPTION: The Spring Gap-Stanislaus Project is located in Calaveras and Tuolumne Counties, CA on the Middle Fork Stanislaus River (Middle Fork) and South Fork Stanislaus River. Owned. The project, operated by Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E), has an installed capacity of 87.9 MW and occupies approximately 1,060 acres of federal land within the Stanislaus National Forest. Both the Middle and South Forks are popular destinations for a variety of outdoor recreation activities. With a section of the lower river designated by the State of CA as a Wild Trout Fishery, the Middle Fork is widely considered to be one of California’s best wild trout fisheries. The South Fork on the other hand, with its high gradient and steep rapids, is a popular whitewater kayaking and rafting destination. A. SUMMARY 1. License application filed: December 26, 2002 2. License Issued: April 24, 2009 3. License expiration: March 31, 2047 4. Capacity: Spring Gap- 6.0 MW Stanislaus- 81.9 MW 5. Waterway: Middle & North Forks of the Stanislaus River 6. Counties: Calaveras, Tuolumne 7. Licensee: Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) 8. Licensee Contact: Pacific Gas and Electric Company P.O. Box 997300 Sacramento, CA 95899-7300 9. Project area: The project is located in the Sierra Nevada mountain range of north- central California. -

The Geography and Dialects of the Miwok Indians

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY VOL. 6 NO. 2 THE GEOGRAPHY AND DIALECTS OF THE MIWOK INDIANS. BY S. A. BARRETT. CONTENTS. PAGE Introduction.--...--.................-----------------------------------333 Territorial Boundaries ------------------.....--------------------------------344 Dialects ...................................... ..-352 Dialectic Relations ..........-..................................356 Lexical ...6.................. 356 Phonetic ...........3.....5....8......................... 358 Alphabet ...................................--.------------------------------------------------------359 Vocabularies ........3......6....................2..................... 362 Footnotes to Vocabularies .3.6...........................8..................... 368 INTRODUCTION. Of the many linguistic families in California most are con- fined to single areas, but the large Moquelumnan or Miwok family is one of the few exceptions, in that the people speaking its various dialects occupy three distinct areas. These three areas, while actually quite near together, are at considerable distances from one another as compared with the areas occupied by any of the other linguistic families that are separated. The northern of the three Miwok areas, which may for con- venience be called the Northern Coast or Lake area, is situated in the southern extremity of Lake county and just touches, at its northern boundary, the southernmost end of Clear lake. This 334 University of California Publications in Am. Arch. -

Delta Sediment Measurements to Support Numerical Modeling of Sediment-Turbidity

Delta sediment measurements to support numerical modeling of sediment-turbidity Scott Wright, David Schoellhamer, Tara Morgan, Dan Whealdon-Haught, Matt Marineau USGS Sacramento CWEMF annual meeting 17 April 2012, Sacramento CA U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Sediment-turbidity modeling in the Delta Delta sediment modeling is useful for a variety of reasons: - fish habitat (e.g. Delta smelt) - tidal wetlands, restoration, sea-level rise - navigation - levee integrity Robust models require data for set- up, calibration, and testing The Delta is large and very complex. Several data gaps exist with respect to development and testing of numerical sediment models We began a project to fill these data gaps in December 2010, funded by the Federal Task Force on the Delta Sediment model data requirements Hydrodynamics: - bathymetry and levee topography - flows and velocities at upstream model boundaries - water levels at downstream boundary and interior - bed roughness (e.g. Manning’s n, drag coefficients) Sediment: - Sediment loads at upstream model boundaries - Sediment concentrations at interior points - Size distributions of sediment on the bed - Sediment erosion/entrainment rates - Size distributions and settling velocities of suspended sediment Sediment-turbidity monitoring 17 turbidity and sediment flux stations, co-located with flow gages Network is designed to monitor incoming sediment loads and track movement of turbidity and sediment throughout the Delta Sediment-turbidity monitoring Sac River @ Freeport Miner -

2000 Angler Survey 1

State of California The Resources Agency DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME CENTRAL VALLEY SALMON AND STEELHEAD HARVEST MONITORING PROJECT 2000 ANGLER SURVEY 1: Prepared by Kyle Murphy Associate Biologist (MarineIFisheries) and Tom Schroyer, Mike Harris, and Duane Massa Biolog~sts(MarineEisheries) -I1 Th~swork was supported by funds provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Comprehensive Assessment & Monitoring Program (CAMP), as part of a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Fish and Game pursuant to the Central Valley Project Improvement Act (PL. 102-575). SUMMARY In October 1992, the Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA) was signed into law. One objective of the CVPIA is to restore the abundance of natural fish stocks in Central Valley rivers and streams. To achieve this objective, the CVPIA requires the development of restoration actions that ensure sustainable, long-term populations of native anadromous fish stocks. Section 3406(b)(16) of the CVPIA specifies the development of a monitoring and assessment program to evaluate the effectiveness of implemented restoration actions. The Comprehensive Assessment and Monitoring Program (CAMP) was established for this purpose. The CAMP program recommends monitoring of both adult and juvenile fish populations. It was recommended that adult monitoring include spawner returns (escapement) as well as in-river recreational, ocean recreational and commercial harvest estimates. In 1998, the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) began the Central Valley Salmon and Steelhead Harvest Monitoring Project to help enumerate the number of adult chinook salmon and steelhead resulting from natural production in Central Valley rivers and streams. This long-term harvest monitoring project will determine annual estimates of the total in-river harvest. -

Indian Grinding Rock State Historic Park Park Is Located in the Sierra Nevada Foothills, Has the Only Known Occurrence of Mortars Eight Miles East of Jackson

Our Mission Indian The mission of California State Parks is to provide for the health, inspiration and education of the people of California by helping “ Grinding Rock to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological t was the Indians’ way diversity, protecting its most valued natural and I cultural resources, and creating opportunities State Historic Park for high-quality outdoor recreation. to pass through a country without disturbing anything; to pass and leave no trace, like a fish California State Parks supports equal access. through the water or birds Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who need assistance should contact the park at through the air.” (209) 296-7488. If you need this publication in an alternate format, contact [email protected]. —Willa Cather, author CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369 (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Indian Grinding Rock SHP Chaw’se Regional Indian Museum 14881 Pine Grove-Volcano Road Pine Grove, CA 95665 (209) 296-7488 • www.parks.ca.gov/ igr © 2002 California State Parks (Rev. 2017) I ndian Grinding Rock State Historic site, Indian Grinding Rock State Historic Park Park is located in the Sierra Nevada foothills, has the only known occurrence of mortars eight miles east of Jackson. The park is intentionally decorated with petroglyphs. nestled in a small valley 2,400 feet above sea level with open meadows and large valley The marble grinding rock is fragile and very oaks that once provided Native Americans susceptible to weathering and chipping. -

Water Quality Control Plan, Sacramento and San Joaquin River Basins

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Amendments to the 1994 Water Quality Control Plan for the Sacramento River and San Joaquin River Basins The Third Edition of the Basin Plan was adopted by the Central Valley Water Board on 9 December 1994, approved by the State Water Board on 16 February 1995 and approved by the Office of Administrative Law on 9 May 1995. The Fourth Edition of the Basin Plan was the 1998 reprint of the Third Edition incorporating amendments adopted and approved between 1994 and 1998. The Basin Plan is in a loose-leaf format to facilitate the addition of amendments. The Basin Plan can be kept up-to-date by inserting the pages that have been revised to include subsequent amendments. The date subsequent amendments are adopted by the Central Valley Water Board will appear at the bottom of the page. Otherwise, all pages will be dated 1 September 1998. Basin plan amendments adopted by the Regional Central Valley Water Board must be approved by the State Water Board and the Office of Administrative Law. If the amendment involves adopting or revising a standard which relates to surface waters it must also be approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) [40 CFR Section 131(c)]. -

11 Atoc Stage 3

Rio Oso Rd Dry Creek Rd Big Ben Rd Rd Bell Garden Hwy Garden Locksley M Mount Pleasant Rd o Ln un North t V New erno n R Airport Rd Auburn Feather River d Atwood Rd Wally Allen Rd Allen Dowd Ave W Wise Rd Rd Mccourtney W Wise Rd Wise Rd Luther Rd Foresthill Rd 70 Crosby Herold Rd Herold Crosby Wise Rd Laurel Ave Nicolaus Ave Fruitvale Rd Fruitvale Rd Hungry Hollow Rd Gold Canal Rd Hill Rd Balderston Rd Virginiatown Rd El Dorado St Marcum Rd Nicolaus Rd Airport Rd 9th St Wentworth Springs Rd American River Trl 193 Fowler Rd El Centro Blvd Auburn Greenwood Rd O St Feather River Lincoln G St Lincoln Newcastle 1st St Ave East 193 Hwy Ln Ophir Rd Nelson Bear Creek Rd 193 Union Valley 99 Moore Rd Moore Rd Indian Hill Rd Reservoir Pleasant Grove Rd 65 49 Mosquito Rd English Colony Road Ridge Darling Taylor Rd Hackomiller Catlett Rd Catlett Rd Way 80 Garden Valley Rd Marshall Rd Rd W Catlett Rd Pacific Ave Athens Ave Whitney Blvd Garden Hwy Sunset Blvd Penryn Rd Dowd Ave Auburn Folsom Rd Howsley Rd Humphrey Rd King Rd EL DORADO Sierra College Blvd College Sierra Prospectors Rd Traverse Creek Rd Pleasant Grove Creek Canal Sunset BlvdRocklin Horseshoe Bar Rd COUNTY Sunset Blvd Industrial Ave Rattlesnake Bar Rd Phillip Rd Pacific StLoomis Fiddyment Rd Mount Murphy Rd Brewer Rd Blue Oaks Blvd Dick Cook Rd Coloma Rd Laird Rd Cross Canal 193 5th St Folsom Rock Creek Rd PLACER Wells Salmon Falls Rd Peavine Ridge Rd El Centro Blvd Rocklin Rd Lake 65 Whitney Blvd Ave 153 Sacramento River Roseville Foothills Blvd Pleasant Springview Dr Pleasant Grove Rd -

OPTION a Draft Amendments to SB 1199 As Approved

OPTION A Formatted: Centered Draft Amendments to SB 1199 as Approved by Amador County Board of Supervisors on June 17, 2014Amended on May 28, 2014 (k) (1) North Fork Mokelumne River from 0.50 miles downstream of the Salt Springs 97-066 Dam to 0.50 miles upstream of the Tiger Creek Powerhouse. (2) North Fork Mokelumne River from 1,000 feet downstream of the Tiger Creek Afterbay 97- 105 Dam to State Highway Route 26. (3) North Fork Mokelumne River from 400 feet downstream of the small reregulating dam at the outlet of the West Point Power House to the southern boundary sec. 12, T6N R12E Middle Fork Mokelumne River confluence. (4) The main stem of the Mokelumne River from the confluence of the North and Middle Forks to 300 feet upstream of the Electra Powerhouse. From 1400 feet upstream of the Middle Fork Mokelumne River confluence to 300 feet upstream of the Electra Power House. (5) The main stem of the Mokelumne River from 300 feet downstream of the small reregulating dam downstream of the Electra Powerhouse to the Pardee Reservoir flood surcharge pool at 580 feet elevation above mean sea level. (6) Nothing in this chapter shall prejudice, alter, delay, interfere with, or affect in any way, the installation, operation, maintenance, repair, and replacement of river flow and water quality monitoring stations and equipment in and along the designated segments of the Mokelumne River; or the construction, operation, maintenance, repair, and replacement of recreational facilities along the Mokelumne River on East Bay Municipal Utility District lands, including scenic trails and rafting facilities, such as take outs, parking lots, and similar recreational facilities. -

Suspended-Sediment Transport Through a Large Fluvial-Tidal Channel Network

SUSPENDED-SEDIMENT TRANSPORT THROUGH A LARGE FLUVIAL-TIDAL CHANNEL NETWORK Scott A. Wright, Research Hydrologist, U.S. Geological Survey, Sacramento, CA, [email protected]; Tara L. Morgan, Hydrologist, U.S. Geological Survey, Sacramento, CA, [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Sacramento – San Joaquin River Delta (the Delta) is formed at the confluence of the Sacramento River and San Joaquin River, the two main watersheds draining California’s Central Valley (Figure 1). Once an extensive tidal marsh system, the Delta has been subject to an array of changes since the discovery of gold and subsequent development of California in the mid- 1800s. These changes include the following: construction of channel levees and draining of tidal marshes for agriculture; hardening (rip-rap) of existing channels and construction of new channels/canals to support water conveyance; hydraulic gold mining activities which introduced large quantities of fine sediment to the Delta in the late 1800s; construction of large dams in the watershed in the mid-1900s that trap sediment and reduce sediment loads to the Delta; construction and ongoing dredging to maintain shipping channels through the Sacramento River (upstream to Sacramento) and San Joaquin River (upstream to Stockton); and the construction of large pumping facilities in the south Delta that export water to the San Joaquin valley and southern California for agricultural and urban uses. These physical modifications have affected the hydrodynamics and sediment transport characteristics of the Delta (Lund et al., 2007, Whipple et al., 2012), which have in turn affected the aquatic ecosystem. In addition to the physical modifications, the ecosystem has been affected by direct biological modifications, in particular the introduction of non-native species. -

Lower Mokelumne River Salmonid Redd Survey Report: October 2011 Through February 2012

Lower Mokelumne River Salmonid Redd Survey Report: October 2011 through February 2012 June 2013 Robyn Bilski and Ed Rible East Bay Municipal Utility District, 1 Winemasters Way, Lodi, CA 95240 Key words: lower Mokelumne River, salmonid, fall-run Chinook salmon, Oncorhynchus mykiss, redd survey, spawning, superimposition, gravel enhancement ___________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Weekly fall-run Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and winter-run steelhead/rainbow trout (O. mykiss) spawning surveys were conducted on the lower Mokelumne River from 19 October 2011 through 28 February 2012. Estimated total escapement during the 2011/2012 season was 18,596 Chinook salmon. The estimated number of in-river spawners was 2,674 Chinook salmon. The first salmon redd was detected on 19 October 2011. During the surveys, a total of 564 salmon redds were identified. Forty-three (7.6%) Chinook salmon redds were superimposed by other Chinook salmon redds and 336 (59.6%) redds were located within gravel enhancement areas. The reach from Camanche Dam to Mackville Road (reach 6) contained 512 (90.2%) salmon redds and the reach from Mackville Road to Elliott Road (reach 5) contained 52 (9.8%) salmon redds. The highest number of Chinook salmon redd detections (161) took place on 22 November 2011. The first O. mykiss redd was found on 22 November 2011. Sixty-eight O. mykiss redds were identified. Nine O. mykiss redds were superimposed on Chinook salmon redds and one O. mykiss redd was superimposed on another O. mykiss redd. Thirty-one (45.6%) O. mykiss redds were located within gravel enhancement areas. Reach 6 contained 51 (75%) redds and reach 5 contained 17 (25%) redds.