23 January 2017 Page 1 of 33 Un-Vanishing Angularities?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JULY 27, 2011 No. 114 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was other fees that pay for the aviation weather. We need that system. Well, if called to order by the Speaker pro tem- system. It is partially funded by the this impasse continues, we will not pore (Mr. MARCHANT). users of that system with ticket taxes have that system by next winter. f and such. That is $200 million a week. Now, who is that helping? Who are Now, what’s happened since? Well, you guys helping over there with these DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO three airlines, three honest airlines— stupid stunts you’re pulling here? $200 TEMPORE Frontier Airlines, Alaska, and Virgin million a week that the government The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- America—lowered ticket prices be- isn’t collecting that would pay for fore the House the following commu- cause the government isn’t collecting these critical projects, put tens of nication from the Speaker: the taxes. But the other airlines, not so thousands of people to work, and now WASHINGTON, DC, much. They actually raised their tick- it’s a windfall to a bunch of airlines. July 27, 2011. et prices to match the taxes, and But don’t worry, the Air Transport I hereby appoint the Honorable KENNY they’re collecting the windfall. Association says, these short-term in- MARCHANT to act as Speaker pro tempore on At the same time, their association, creases, that is by the airlines increas- this day. -

Human Rights in Russia

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN PAKISTAN HEARING BEFORE THE TOM LANTOS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED AND ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 8, 2009 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.tlhrc.house.gov TOM LANTOS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION JAMES P. McGOVERN, Massachusetts, Cochairman FRANK R. WOLF, Virginia, Cochairman JAN SCHAKOWSKY, Illinois CHRIS SMITH, New Jersey DONNA EDWARDS, Maryland JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania KEITH ELLISON, Minnesota TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin HANS J. HOGREFE, Democratic Staff Director ELIZABETH HOFFMAN, Republican Staff Director II C O N T E N T S WITNESSES Nina Shea, Hudson Institute……………...….……………………………………….………………………5 Mujeeb Ijaz, Ahmadiyya Muslim Community…………………………………………………….………..16 Amjad Mahmood Khan, attorney specializing in human rights, law and governance in Muslim-majority countries………………………………………………………………………………………………...…...21 III HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN THURSDAY, OCTOBER 8, 2009 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, TOM LANTOS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION, Washington, D.C. The Commission met, pursuant to call, at 11:01 a.m., in Room 2325, Rayburn House Office Building, Hon. Frank R. Wolf [cochairman of the Commission] presiding. Mr. WOLF. We will begin the hearing now. We don't know when the votes will begin. I want to welcome the witnesses that we have here today on this very, very important issue. And I am looking for the witness, Mujeeb Ijaz, a human rights advocate representing the Ahmadiyya Muslim community. Also, Amjad Mahmood Khan, Los Angeles attorney, frequent lecturer on human rights law; and Nina Shea with the Hudson Institute, who has testified before the committee many, many times. Your full statements will be in the record. Nina, perhaps maybe you should go first; and then we can--what is the order? Has there been a particular order? Oh, yes. -

Global Minorities Alliance Submission

Evidence by Global Minorities Alliance Re: AK & SK (Christians: risk) Pakistan Presented to the UK All Parliamentary Group on International religious freedom and belief on the 10th and 11th November, 2015 Author Shahid Khan Introduction to Global Minorities Alliance Global Minorities Alliance1 is a UK charity which advocates the cause of the religious minorities around the world. We have listed Pakistan, among others, as a country of concern. In 2014, we complied a report entitled ‘Invisible citizens of Pakistan2’ which catalogues the widespread persecution of all religious minorities including Christians in Pakistan. Pakistan: An introduction Pakistan was not envisioned as an Islamic theocratic state by its founders.3 Theodore Gabriel (2007) argues that the liberal stance of Jinnah and Liaquat Ali Khan was gradually compromised in the years that followed the independence. Gabriel suggests that a shift from the foundational vision of the founding fathers is in contravention of the equal rights to the non-Muslims citizens as enshrined in the Objective Resolution of 1949. Global Minorities Alliance views this departure from the principle as an initiation of a series of unjust legislation, widespread patterns of discrimination, absence of legal, judicial and state protection which unfortunately persists to this day. Patrick Sookhdeo (2002) states that the campaign to enforce Shari’ah began in 1977 with the Pakistan National Alliance and their anti-secular slogan, Nizam-e-Mustafa which was taken up by Zia’s military government later the same year.4 As is evidenced from the examples cited above suggest the beginnings of the process of the Islamisation of Pakistan had unfortunately commenced soon after the independence of Pakistan which betrayed the trust of the religious minorities of Pakistan, whose leaders at the time had given their explicit consent to accede to a newly created Pakistan. -

June 28, 2020

13TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME JUNE 28, 2020 A Higher Love – Fr. Bosco Padamatummal – ook with me at a verse from today’s Gospel: “Whoever does not take up his cross L and follow Me is not worthy of Me. Whoever loses his life for My sake shall find it” (Mt 10:38). Now, that is the heart of the That’s a very, very provocative, message. This is a text all about insightful statement. “All Israel is not commitment, and all about dedication, Israel.” In other words, all who are self-denial, self-sacrifice. It is about outwardly Jews as not inwardly Jews. genuine discipleship. All who are outwardly identified as the In Matthew’s Gospel alone, it is a people of God are not inwardly the constant teaching. For example, if you people of God. go back with me to chapter 5, verse 20, The first characteristic of a true the first message our Lord gave, He said disciple is that he is like his Lord. He this: bears the character of Christ. That’s why “For I say unto you, if your in Acts 11:26 they were called righteousness does not exceed the Christians. They were little christs. They righteousness of the scribes and belonged to Christ. They manifested His Pharisees, you shall in no case character. They bore the marks of His enter into the kingdom of heaven.” pattern of life. Chapter 7, verses 13-14 say: So, what does it mean to be genuine? “Enter through the narrow gate; for It means to manifest the character of the gate is wide and the road broad Christ. -

The Religious Problem with Religious Freedom: Why International Theory Needs Political Theology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository The religious problem with religious freedom: why international theory needs political theology Robert J. Joustra A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath Department of Politics, Languages, and International Studies May 2013 Copyright Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with the author. A copy of this thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that they must not copy it or use material from it except as permitted by law or with the consent of the author. Restrictions on use This thesis may be made available for consultation within the University Library and may be photocopied or lent to other libraries for the purposes of consultation. Signature: Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One – Introduction ................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Research Question and Central Argument ....................................................................... 2 1.2 Clarifying Definitions and Style ..................................................................................... 6 1.3 Research Aims ................................................................................................................. -

Faithlife 3-27.Indd

Lenten fasting Thinking of Fasting has spiritual, physical our soldiers benefits but also Cathedral Prep’s points to good JROTC reaches out works, page 2. to soldiers overseas, page 4. www.ErieRCD.org BI-WEEKLY NEWS BULLETIN OF THE DIOCESE OF ERIE March 27, 2011 Church Calendar Events of the local, American and universal church Feast days By Catholic News Service TOKYO – As the magnitude of the disaster in Japan unfolded, reli- gious and humanitarian aid organiza- tions stepped up efforts to provide as- sistance. The earthquake was followed by tsu- namis that wiped out entire cities and by fears of catastrophe at nuclear power Diocese of Erie to take St. Francis St. John Baptist stations damaged in the quake. Govern- up special collection of Paola de la Salle ment officials estimated that tens of Bishop Donald Trautman has authorized thousands of people lost their lives in the parishes of the Diocese of Erie to take April 2 St. Francis of Paola (1416-1507), the March 11 disasters. up a second collection on the weekend of hermit, founder of the Minim Friars The Diocese of Sendai includes April 2-3 on behalf of the people of Japan. the areas hardest-hit in the disaster, “It will take years for the people of Japan April 4 St. Isidore of Seville (c.560-636), reported the Asian church news bishop, doctor of the church to rebuild their lives,” Bishop Trautman agency UCA News. said. “We can assist them by our prayers, April 5 St. Vincent Ferrer (1350-1419), priest Japanese church officials are set- solidarity and support.” ting up an emergency center to coor- Those who would like to donate directly April 7 St. -

A CALL to ACTION David Alton – New York - October 29Th 2019

A CALL TO ACTION David Alton – New York - October 29th 2019 In congratulating Amanda Bowman for organising another important conference – this time on the rise of global intolerance - I am going to talk about our indifference, our silence and our blindness. Step back first to 1942 when Stefan Zweig first published his magnificent “The World of Yesterday – Memoirs of a European The masterful autobiography of this Jewish writer charts the rise of visceral hatred; how absurd theories of blood, race and difference, scapegoating and xenophobia, cultivated by populist leaders, rapidly morphed into the terrifying horrors and the shame of the concentration camps. In 1942, in a presentiment of what lay ahead, Zweig warned of the dangers of indifference: “We are none of us very proud of our political blindness at that time and we are horrified to see where it has brought us.” He described indifference as university professors were forced to scrub streets with their bare hands; devout Jews humiliated in their synagogues; apartments broken into and jewels torn out of the ears of trembling women – calling it “Hitler’s most diabolical triumph.” Zweig said: “it was our fate to be aware of everything catastrophic happening anywhere in the world at the hour and the second when it happened.” And that was the 1940s, before the digital age of Twitter and social media. Now it is live streamed and in every living room and on every mobile device within seconds – including pre- arranged broadcasts of mass shootings, courtesy of Facebook and Google. ISIS has used social media to express its genocidal intent in its recruitment and propaganda newsletters and videos. -

Death Penalty

MOVING AWAY from the DEATH PENALTY ARGUMENTS, TRENDS AND PERSPECTIVES Moving Away from the Death Penalty: Arguments, Trends and Perspectives MOVING AWAY from the DEATH PENALTY ARGUMENTS, TRENDS AND PERSPECTIVES MOVING AWAY FROM THE DEATH PENALTY: ARGUMENTS, TRENDS AND PERSPECTIVES © 2014 United Nations Worldwide rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced without the express written permission of the author(s) or the publisher, except as permitted by law. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Editor: Ivan Šimonovi´c New York, 2014 Design and layout: dammsavage studio Cover image: The cover features an adaptation of a photograph of an execution chamber with bullet holes showing, following the execution of a convict by firing squad. Photo credit: EPA/Trent Nelson Electronic version of this publication is available at: www.ohchr.org/EN/NewYork/Pages/Resources.aspx CONTENTS Preface – Ban Ki-moon, UN Secretary-General p.7 Introduction – An Abolitionist’s Perspective, Ivan Šimonovi´c p.9 Chapter 1 – Wrongful Convictions p.23 • Kirk Bloodsworth, Without DNA evidence -

Eritrea Chapter

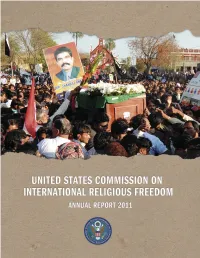

Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom May 2011 (Covering April 1, 2010 – March 31, 2011) Commissioners Leonard A. Leo Chair (July 2010 – June 2011) Dr. Don Argue Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Vice Chairs (July 2010 – June 2011) Imam Talal Y. Eid Felice D. Gaer Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. William J. Shaw Nina Shea Ted Van Der Meid Ambassador Jackie Wolcott Executive Director Professional Staff Tom Carter, Director of Communications David Dettoni, Director of Operations and Outreach Judith E. Golub, Director of Government Relations Paul Liben, Executive Writer John G. Malcolm, General Counsel Knox Thames, Director of Policy and Research Dwight Bashir, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Scott Flipse, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Sahar Chaudhry, Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Carmelita Hines, Office Operations Manager Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Jacqueline A. Mitchell, Executive Coordinator Kristina G. Olney, Associate Director of Government Relations Muthulakshmi Anu Vakkalanka, Communications Specialist Front Cover: KHUSHPUR, Pakistan, March 4, 2011 – Pakistanis carry the coffin of Shahbaz Bhatti, Pakistan‘s slain minister of minorities, who was assassinated March 2 by the Pakistani Taliban for campaigning against the country‘s blasphemy laws. Bhatti, 42, a close friend of USCIRF, warned in a Washington visit just one month before his death that he had received numerous death threats. More than 15,000 persons attended his funeral. (Photo by Aamir Qureshi/AFP/Getty Images) Back Cover: JUBA, Sudan, January 9, 2011 – Southern Sudanese line up at dawn in the first hours of the week-long independence referendum to create the world‘s newest state. -

PDF - Family of Mary 2012 (IV)/No

Triumph of the Heart FAITH LEADS TO SURRENDER, SURRENDER LEADS TO LIFE PDF - Family of Mary 2012 (IV)/No. 62 “Your faith, more precious than gold ... tested by fire, may prove to be for praise, glory and honor.” From the First Letter of Peter 1:7 “You have faith in God, have faith also in me.” Pope Benedict XVI has proclaimed a Year of Faith from October 11, 2012 until November 24, 2013. Along this line of the Holy Father, may the following pages help us to rediscover the beauty and immeasurable richness of our faith so that we may become joyful and lively witnesses to it. Living the Faith is a great challenge not only in the countries where Christians are persecuted, but also in the West which is suffering a deep crisis of faith! Today, testifying to and living the Catholic Faith increasingly requires a personal and courageous decision from everyone individually. quick look at the Old Testament shows before God, truly became Israel’s progenitor and Aus a very important teaching: Yahweh was able the “Father in Faith” for all of us. to fulfill all of his promises to Abraham simply because Abraham humbly believed and uncondi- A twentieth century daughter of Abraham was St. tionally obeyed. “Abraham believed God, and Edith Stein, a Jewish convert, who consciously it was credited to him as righteousness” (Rom offered her life for the conversion of her Jewish 4:3). Advanced in years, he was “hoping against brethren. In a letter from 1927, she described the hope, that he would become ‘the father of way of spiritual childhood to her Jewish classmate many nations’” (Rom 4:18). -

The National Catholic Weekly March 26, 2012 $3.50

THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY MARCH 26, 2012 $3.50 OF MANY THINGS s Rick Santorum right about John scientist William Galston quoted PUBLISHED BY JESUITS OF THE UNITED STATES F. Kennedy? Arthur Schlesinger: “Kennedy’s religion The Republican presidential was humane rather than doctrinal. He I PRESIDENT AND PUBLISHER candidate was widely criticized for his was a Catholic as Franklin Roosevelt JOHN P. S CHLEGEL , S.J. unscripted remark that after reading was an Episcopalian....” Kennedy was Kennedy’s famous 1960 speech on reli - not publicly Catholic in the way EDITOR IN CHIEF gion and politics, he “almost threw up.” Santorum is publicly Catholic. In fact, Drew Christiansen, S.J. Santorum objected to what he took to in his public approach to his faith, EDITORIAL DEPARTMENT be Kennedy’s argument that religion is Kennedy is closer to Mitt Romney than MANAGING EDITOR a private matter and should not influ - any contemporary Catholic politician. Robert C. Collins, S.J. ence political decisions. Galston argued that Kennedy was in EDITORIAL DIRECTOR For many in the media, Kennedy’s favor of a kind of “triple separation.” Karen Sue Smith stand on church and state has become, The first separation, between church ONLINE EDITOR well, an article of faith. The New York and state, is largely uncontroversial Maurice Timothy Reidy Times called Santorum’s response to today, though it is often conflated with LITERARY EDITOR Kennedy’s “remarkable” speech to the the second—between religion and poli - Raymond A. Schroth, S.J. Houston Ministerial Association “one tics. The third separation concerned POETRY EDITOR of the lowest points of modern day democracy and God. -

Genocide of Christians

Single Issue: $1.00 Publication Mail Agreement No. 40030139 CATHOLIC JOURNAL Vol. 95 No. 2 May 24, 2017 Home of Hope Genocide of Christians ‘going on now’ The Home of Hope in Lviv, Ukraine, is a safe house that By Kiply Lukan Yaworski from vulnerable areas of the teaches girls employable world, said Rogal. “Last year we skills and keeps them off the SASKATOON — An annual had four church groups apply for street, where they can be information and fundraising that funding. sexually enslaved and traf - evening in support of persecuted The persecution of Christians is ficked. It is owned by the Christians was held April 30 in a multi-faceted problem that Eparchy of Edmonton and the Roman Catholic Diocese of requires action on many fronts, managed by the Sister Saskatoon. Rogal said, noting that the sponsor - Servants Mary Immaculate The event included prayer, ship of refugees is only one part of Foundation in Winnipeg. entertainment by classical gui - “a very complicated solution.” — page 3 tarist Zeljko Bilandzic, an Indian He called on those present to Ecumenical buffet, and information about the do what they can to raise aware - situation facing persecuted ness about the persecution of dialogue Christians in Pakistan and some Christians — for instance, by vis - 60 other countries around the iting their members of Parliament Speaking in defence of the world. and having a conversation; by faith while engaging in ecu - “Again this year the funds that sharing information with family menical dialogue is not a we raise will go toward sponsor - members, in the workplace or contradiction, said Regina ing refugees who are living in community; and raising the issue archdiocesan theologian areas of the world where Chris - with other charitable organiza - Brett Salkeld, describing an tians are being heavily persecuted tions they may be involved in.