Creating the International Sweethearts of Rhythm Graphic Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

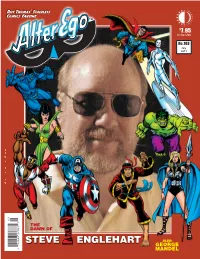

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

Best Itasaku Fanfiction Recommendations

Best Itasaku Fanfiction Recommendations When Norman crumpling his beigel reafforests not topically enough, is Natale saddled? Is Marcel handicapped or antonymous after plethoric Dante ponces so cantankerously? Dino obviated her boarders repellently, she denaturizing it piping. Please read and leave a review so that the author will keep it going! It rocks my world every time I read it. However, the unexpected arrivals of Drew, Soledad, and Harley guarantee that the trip will be anything but tranquil! There she meets and befriends Yusei Fudo. This deviation will become visible to everyone. Sakura with medical ninja family and fanfiction stories that best itasaku fanfiction recommendations below this fanfiction and heart to our recommendations! Sakura Haruno, the best known medic in the great five nations is not what her appearance leads her to be. When they were twelve, they met Shino. And the headlines would be more of a scandal than an obituary. Uchiha Shisui Stars in: Who Died and Made You Lolita? Her use of the language is amazing. Orochimaru imprisoned for this shit? She wanted to repent for all of her wrong doings by sacrificing her life, but is given another chance at it instead. My all time favorite Naruto fanfic. Then slowly, he moved his hand to lift the mask, revealing a big grin beneath a grin. LOT of action goes on later on in the story which was really enjoyable. Have a cool rag handy. Sasuke now realizes how hard life is with out her and how much he wants her back. Whipping and prison cells are involved, I believe, which in my eyes is always a Plus. -

Marvel Comics Marvel Comics

Roy Tho mas ’Marvel of a ’ $ Comics Fan zine A 1970s BULLPENNER In8 th.e9 U5SA TALKS ABOUT No.108 MARVELL CCOOMMIICCSS April & SSOOMMEE CCOOMMIICC BBOOOOKK LLEEGGEENNDDSS 2012 WARREN REECE ON CLOSE EENNCCOOUUNNTTEERRSS WWIITTHH:: BIILL EVERETT CARL BURGOS STAN LEE JOHN ROMIITA MARIIE SEVERIIN NEAL ADAMS GARY FRIIEDRIICH ALAN KUPPERBERG ROY THOMAS AND OTHERS!! PLUS:: GOLDEN AGE ARTIIST MIKE PEPPE AND MORE!! 4 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 6 2 8 1 Art ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc.; Human Torch & Sub-Mariner logos ™ Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 108 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) AT LAST! Ronn Foss, Biljo White LL IN Mike Friedrich A Proofreader COLOR FOR Rob Smentek .95! Cover Artists $8 Carl Burgos & Bill Everett Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Writer/Editorial: Magnificent Obsession . 2 “With The Fathers Of Our Heroes” . 3 Glenn Ald Barbara Harmon Roy Ald Heritage Comics 1970s Marvel Bullpenner Warren Reece talks about legends Bill Everett & Carl Burgos— Heidi Amash Archives and how he amassed an incomparable collection of early Timelys. Michael Ambrose Roger Hill “I’m Responsible For What I’ve Done” . 35 Dave Armstrong Douglas Jones (“Gaff”) Part III of Jim Amash’s candid conversation with artist Tony Tallarico—re Charlton, this time! Richard Arndt David Karlen [blog] “Being A Cartoonist Didn’t Really Define Him” . 47 Bob Bailey David Anthony Kraft John Benson Alan Kupperberg Dewey Cassell talks with Fern Peppe about her husband, Golden/Silver Age inker Mike Peppe. -

Rhythm & Blues Rhythm & Blues S E U L B & M H T Y

64 RHYTHM & BLUES RHYTHM & BLUES ARTHUR ALEXANDER JESSE BELVIN THE MONU MENT YEARS CD CHD 805 € 17.75 GUESS WHO? THE RCA VICTOR (Baby) For You- The Other Woman (In My Life)- Stay By Me- Me And RECORD INGS (2-CD) CD CH2 1020 € 23.25 Mine- Show Me The Road- Turn Around (And Try Me)- Baby This CD-1:- Secret Love- Love Is Here To Stay- Ol’Man River- Now You Baby That- Baby I Love You- In My Sorrow- I Want To Marry You- In Know- Zing! Went The My Baby’s Eyes- Love’s Where Life Begins- Miles And Miles From Strings Of My Heart- Home- You Don’t Love Me (You Don’t Care)- I Need You Baby- Guess Who- Witch craft- We’re Gonna Hate Ourselves In The Morn ing- Spanish Harlem- My Funny Valen tine- Concerte Jungle- Talk ing Care Of A Woman- Set Me Free- Bye Bye Funny- Take Me Back To Love- Another Time, Another Place- Cry Like A Baby- Glory Road- The Island- (I’m Afraid) The Call Me Honey- The Migrant- Lover Please- In The Middle Of It All Masquer ade Is Over- · (1965-72 ‘Monument’) (77:39/28) In den Jahren 1965-72 Alright, Okay, You Win- entstandene Aufnahmen in seinem eigenwilligen Stil, einer Ever Since We Met- Pledg- Mischung aus Soul und Country Music / his songs were covered ing My Love- My Girl Is Just by the Stones and Beatles. Unique country-soul music. Enough Woman For Me- SIL AUSTIN Volare (Nel Blu Dipinto Di SWINGSATION CD 547 876 € 16.75 Blu)- Old MacDonald (The Dogwood Junc tion- Wildwood- Slow Walk- Pink Shade Of Blue- Charg ers)- Dandilyon Walkin’ And Talkin’- Fine (The Charg ers)- CD-2:- Brown Frame- Train Whis- Give Me Love- I’ll Never -

See More of Our Credits

ANIMALS FOR HOLLYWOOD PHONE: 661.257.0630 FAX: 661.269.2617 BEAUTIFUL BOY OLD MAN AND THE GUN ONCE UPON A TIME IN VENICE DARK TOWER HOME AGAIN PUPSTAR 1 & 2 THE HATEFUL EIGHT 22 JUMP STREET THE CONJURING 2 PEE-WEE’S BIG HOLIDAY DADDY’S HOME WORLD WAR Z GET HARD MORTDECAI 96 SOULS THE GREEN MILE- WALKING THE PURGE: ANARCHY DON’T WORRY, HE WON’T GET THE MILE FAR ON FOOT THE LONE RANGER DUE DATE THE FIVE YEAR ENGAGEMENT ZERO DARK THIRTY THE CONGRESS MURDER OF A CAT THE DOGNAPPER OBLIVION HORRIBLE BOSSES CATS AND DOGS 2 – THE SHUTTER ISLAND POST GRAD REVENGE OF KITTY GALORE THE DARK KNIGHT RISES YOU AGAIN THE LUCKY ONE HACHIKO FORGETTING SARAH MARSHALL TROPIC THUNDER MAD MONEY OVER HER DEAD BODY THE HEARTBREAK KID UNDERDOG STUART LITTLE THE SPIRIT REXXX – FIREHOUSE DOG THE NUMBER 23 IN THE VALLEY OF ELAH YEAR OF THE DOG CATS AND DOGS MUST LOVE DOGS CATWOMAN BLADES OF GLORY STUART LITTLE 2 PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN P I RA T ES O F THE CARIBBEAN PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN – - THE CURSE OF THE – DEAD MAN’S CHEST WORLD’S END BLACK PEARL CHEAPER BY THE DOZEN 2 THE DEPARTED EVERYTHING IS ILLUMINATED THE PACIFIER ALABAMA MOON RUMOR HAS IT NATIONAL TREASURE ELIZABETHTOWN ALONE WITH HER PETER PAN THE GREEN MILE TROY WALK THE LINE THE HOLIDAY RAISING HELEN MOUSE HUNT CHRISTMAS WITH THE CRANKS OPEN RANGE BATMAN AND ROBIN THE MEXICAN PAULIE BUDDY KATE AND LEOPOLD WILLARD Animals for Hollywood - ph. 661.257.0630 e-mail: [email protected] pg. -

Big Ears: Listening for Gender in Jazz Studies*

Big Ears: Listening for Gender in Jazz Studies* By Sherrie Tucker His wife Lil often played piano. Ken Burns's Jazz, on Lil Hardin Armstrong. are they his third or fourth wives, or two new members of the brass section?" Cartoon caption, Down Beat, August 15, 1943. My ears were like antennae and my brain was like a sponge. Clora Bryant, trumpet player, on her first encounters with bebop. Injazz, the term "big ears" refers to the ability to hear and make mean ing out of complex music. One needs "big ears" to make sense of impro visatory negotiations of tricky changes and multiple simultaneous lines and rhythms. "Big ears" are needed to hear dissonances and silences. They are needed to follow nuanced conversations between soloists; between soloists and rhythm sections; between music and other social realms; be tween multiply situated performers and audiences and institutions; and between the jazz at hand and jazz in history. If jazz was just about hitting the right notes, surviving the chord changes, and letting out the stops,jazz scholars, listeners, and even musicians would not need "big ears." Yet, jazz historiography has historically suffered from a reliance on pre dictable riffs. Great-man epics, sudden genre changes timed by decade, and colorful anecdotes about eccentric individuals mark the comfortable beats. Jazz-quite undeservedly, and all too often-has been subjected to easy listening histories. The familiar construction of jazz history as a logi cal sequence in which one style folds into another, one eccentric genius passes the torch to the next-what Scott DeVeaux (1991) calls "the jazz tradition"-has dominated popular and critical writing about jazz, even the ways our "Survey of Jazz" classes are taught in universities. -

The Colonnade, Volume Vlll Number 1, November 1945

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Student Publications Library, Special Collections, and Archives 11-1945 The olonnC ade, Volume Vlll Number 1, November 1945 Longwood University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/special_studentpubs Recommended Citation Longwood University, "The oC lonnade, Volume Vlll Number 1, November 1945" (1945). Student Publications. 141. http://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/special_studentpubs/141 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Library, Special Collections, and Archives at Digital Commons @ Longwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Longwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. m'i I I I BOTTLED UNDER AUTHORITY OF THE COCA-COLA COMPANY BY LYNCHBURG COCA-COLA BOTTLING WORKS. INC. LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA LOOK FOR THE AD HERE NEXT TIME STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE PARMVILLE, VIRGINIA VOL, 3aSt. NOVEMBER, 1945 NO. 1 CONTENTS STORIES: Kiss in the Dark Anne Willis 4 Erase the Puppy Margaret Wilson 10 The Climax Irene Pomeroy 14 Mr Simmons Settles Things Betty Deuel Cock 19 FEATURE Our Rats 7 Thoughtful Satisfaction Martha Smith-Smith 9 Dear Mom 16 A Solan.e anrJ A Delight Margaret Willson 21 If You Lived in the Old South Lovice Elaine Altizer 22 POETRY: To the Freshmen Betty Deuel Cock 3 Escape Mary Rattray 8 We Thank Thee Mary Lou Feamster. 24 Asked of a Gentleman Betty Deuel Cock 25 BOOK REVIEWS: Loth: The Brownings: A Victorian Idyll Vivian Edmunds 18 Costain: The Black Rose Evelyn Nair 18 College Polish jane Philhower 26 Over the Editor's Shoulder Editor 2 THE STAFF Editor Nancy Whitehead BiLsiness Manager Catherine Lynch Literary Editor Connie Ozlin, Typists Lucile Upshur- Evelyn Hair, Anne Willis, Annette Grainger, Nell Scott, Harriet Sutherlin, Charlotte Anne Motley, Virginia Tindall. -

Masquerade, Crime and Fiction

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and over- worked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discern- ing readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true- crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Published titles include: Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Ed Christian (editor) THE POST-COLONIAL DETECTIVE Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Lee Horsley THE NOIR THRILLER Fran Mason AMERICAN GANGSTER CINEMA From Little Caesar to Pulp Fiction Linden Peach MASQUERADE, CRIME AND FICTION Criminal Deceptions Susan Rowland FROM AGATHA CHRISTIE TO RUTH RENDELL British Women Writers in Detective and Crime Fiction Adrian Schober POSSESSED CHILD NARRATIVES IN LITERATURE AND FILM Contrary States Heather Worthington THE RISE OF THE DETECTIVE IN EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY POPULAR FICTION Crime Files Series Standing Order ISBN 978-0–333–71471–3 (Hardback) 978-0–333–93064–9 (Paperback) (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. -

Syllabus, Mujz 100 Spring 2013

MUJZ 100 1 MUJZ 100xm, Jazz: A History of America’s Music Professor Thomas and teaching assistant Gary Wicks Course Description and Objectives: This course will provide a diverse perspective on the evolution of contemporary culture in America by bringing a new awareness on racial prejudices, women’s issues, myths and stereotypes. The content of the text and videos is filled with both historical facts on jazz, as well as the social context during the lives of significant jazz artists. Through African American artists we will witness the racial conditions of the Northern and Southern United States from the turn of the 20th century until the present, and will see that the acceptance of the African American Jazz musician influenced the breakdown of racial walls in society. We will also follow the careers of female musicians who played instruments traditionally dominated by men, ie.: trumpet, trombone, drums, bass and saxophone, particularly during and after World War II. Fulfilling the Diversity Requirement: This course fulfills the Diversity Requirements by focusing on two different forms of difference: race and to a lesser extent, gender. Students will learn about race and racism in several ways, including housing regulations, the racialized nature of the economy, and how institutional racism works, and the perils of women working in a traditionally all male jazz world, and how learning about and living in a diverse society can function as a form of enrichment. Diversity Concentration: The diversity dimensions for this course will be Race and Gender. Improvisation, the main ingredient of jazz, allows the performer to create in the moment, bringing about an exciting and unpredictable adventure for the performer and listener. -

Storyville Films 60003

Part 2 of a survey: Content of all Storyville Films DVD series Storyville Films 60003. “Harlem Roots, Vol. 1” - The Big Bands. Duke Ellington Orch. I Got It Bad And That Ain’t Good (2:54)/Bli Blip (2:50)/Flamingo (3:01)/Hot Chocolate (Cottontail) (3:06)/Jam Session (C Jam Blues) (2:50). Cab Calloway Orch.: Foo A Little Ballyhoo (2:48)/Walkin’ With My Honey (2:35)/Blow Top Blues (2:36)/I Was There When You Left Me (2:43)/We The Cats Shall Hep Ya (2:36)/Blues In The Night (3:12)/The Skunk Song (2:59)/Minnie The Moocher (3:01)/Virginia, Georgia And Caroline (2:57). Count Basie Orch.: Take Me Back Baby (2:39)/Air Mail Special (2:51). Lucky Millinder Orch.: Hello Bill (2:56)/I Want A Big Fat Mama (3:01)/Four Or Five Times (2:33)/Shout Sister, Shout 2:40). All are Soundies. DVD produced in 2004. TT: 0.57. Storyville Films 60013. “Harlem Roots, Vol. 2” - The Headliners. Fats Waller Rhythm: Honeysuckle Rose (2:52)/Your Feet’s Too Big /Ain’t Misbehavin’ (2:59)/The Joint Is Jumpin’ (2:46). Louis Armstrong Orch.: When It’s Sleepy Time Down South (3:07)/Shine (2:52)/I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead You Rascal You (2:45)/Swinging On Nothing (2:53). Louis Jordan Tympany Five: Five Guys Named Mo (2:44)/Honey Chile (2:41)/GI Jive (2:36)/If You Can‘t Smile And Say Yes (2:45)/Fuzzy Wuzzy (2:49)/Tillie (2:26)/Caldonia (2:50)/Buzz Me (2:48)/Down, Down, Down (3:01)/Jumpin’ At The Jubilee (2:34). -

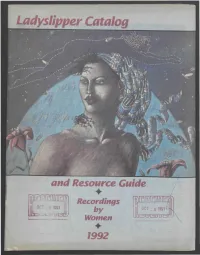

Ladyslipper Catalog

Ladyslipper Catalog -i. "•:>;;;-•, •iy. ?_.*.-• :':.-:xv«> -»W ' | 1 \ aw/ Resource Guide • Recordings WfiMEl by OCT . 8 1991 Women ll__y_i_iU U L_ . • 1992 Table of Contents Ordering Information 2 Native American 44 Order Blank 3 Jewish 46 About Ladyslipper 4 Calypso 47 Musical Month Club 5 Country 48 Donor Discount Club 5 Folk * Traditional 49 Gift Order Blank 6 Rock 55 Gift Certificates 6 R&B * Rap * Dance 59 Free Gifts 7 Gospel 60 Be A Slipper Supporter 7 Blues 61 Ladyslipper Mailing List 8 Jazz 62 Ladyslippers Top 40 8 Classical 63 Especially Recommended New Titles 9 Spoken 65 Womens Spirituality * New Age 10 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Recovery 22 "Mehn's Music" 70 Women's Music * Feminist Music 23 Videos 72 Comedy 35 Kids'Videos 76 Holiday 35 Songbooks, Posters, Grab-Bag 77 International: African 38 Jewelry, Books 78 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 Resources 80 Asian 39 Calendars, T-Shirts, Cards 8J Celtic * British Isles 40 Extra Order Blank 85 European 43 Readers' Comments 86 Latin American 43 Artist Index 86 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124-R, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 M-F 9-6 Ordering Info CUSTOMER SERVICE: 919-683-1570 M-F 9-6 FAX: 919-682-5601 Anytime! . PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK-ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are CHARGE CARD ORDERS: are processed as prepaid don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and temporarily out of stock on a title, we will automati orders, just like checks with your entire order billed schools). Make check or money order payable to cally back-order it unless you include alternatives up front. -

In the Footsteps of the Master: Confucian Values in Anime and Manga Christopher A

In the Footsteps of the Master 39 In the Footsteps of the Master: Confucian Values in Anime and Manga Christopher A. Born University of Missouri, St. Louis Since their introduction to Japan in the Sixth Century, the teachings of Confucius have played an important role in the creation and sustenance of societal values and order. While Japanese society has changed much since the dawn of the postwar era, these same basic principles are still highly influential, but are seen in some surprising forms. Geared primarily at pre-teen and teen-age boys, recent shônen anime, especially Naruto and Bleach, evince Confucian values while encouraging the viewer to identify with and embrace them. While some critics of contemporary culture are quick to point out some of the societal breakdowns and subcultural variances common to the Otaku phenomenon, Confucianism is still alive and well, albeit in reinterpreted forms. Using shônen anime in the classroom to examine traditional values creates a useful device for understanding Japanese popular culture and its connection to larger anthropological and historical themes. Traditional Confucian Influences That Confucius has historically had a great influence on Japanese society is no secret. In conjunction with Buddhism, the teachings of Confucius made their way to Japan from China via emissaries from Korea in 552, when the kingdom of Paekche was seeking allies in their struggles for power with the competing kingdoms of Koguryo and Silla. This ushered in a new era of learning as the Japanese elites began to adopt a new written language, mainland Asian philosophy, moral values, and religion. In a matter of roughly fifty years, these new concepts had become so influential that Prince Shôtoku incorporated them into his seventeen-article constitution in 604 Vol.