Stones and Bones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inspector Candidate Qualifications

Inspector Candidate Qualifications Before you submit your questionnaire, please review the following information regarding our qualifications. You must first be approved (meet our qualifications) before you are invited to our Certification Training. Inspection Experience: You must have solely conducted the minimum of at least 250 number of commercial and/or residential inspections in which you were required to independently document the finding in a written report and to assess the physical condition of building and building systems including the roof, foundation, exterior walls, interior walls, electrical systems, mechanical systems, and all inspectable items associated with a multifamily commercial building. (This does not include termite inspections, appraisals, and site visits from property owners, managers, or real estate brokers.) * PLEASE NOTE THAT UNIT INSPECTIONS ARE NOT CONSIDERED AS A PROPERTY INSPECTION. Computer Skills: You must be able to perform the following: Emails: Send and receive messages Send an attached document with an e-mail Receive and open an attached document Access e-mails on a computer other than your primary computer Internet: Access a web site Search using a search engine tool Submit information to a web site successfully Download files and save them to a specific location on the computer Using Windows: Navigate in different folders Open and use multiple software applications at a time Create, copy, move, rename, and delete files and folders Install new software Use a computer to conduct inspections Technical Knowledge and/or General Knowledge in Residential and/or Commercial Building Trades The below list of major building trades used in commercial and residential construction, indicates those in which you must have technical knowledge or general knowledge. -

Micro Flint-Knapping by Craig Libuse

Micro Flint-Knapping by Craig Libuse Scaling traditional techniques to extremely small sizes Dan White (pictured) has been able to create his own form of art, based on what was one of the first forms of art—flint-knapping (shaping stone by breaking off chips). He calls it "micro-knapping". Prehistoric cultures learned early on that flint could be chipped to create sharp edges for knives, arrow and spear tips. The ability to make quality points was critical, as it meant the difference between eating and going hungry. Shape and size varied widely based on use and culture, but the technique has changed very little in thousands of years. Old points are popular among collectors, and some modern craftsmen have taken to duplicating the ancient techniques, but Dan has taken it to the extreme small end of the size scale. Over the last few years Dan has made over 100 miniature stone arrowheads. He uses a stereo microscope to reproduce the stone-age technology of flint-knapping in miniature. After months of experimenting, headaches, and stabbing himself in the fingers, he has been able to develop a technique where he can make miniature stone arrowheads the size of a grain of rice that have all the same proportions and flaking as the full-size originals. Each miniature takes between 1 and 2 hours to complete. Tools of a new micro-trade His tool kit consists of a thick rubber pad, a fine grinding stone, various size small nails/pins for use as pressure flakers and Scotch tape. (He must wrap his finger 4 or 5 times with tape to prevent the smaller nails from stabbing him while flaking). -

Deciphering the Behavioural Heritage of Knapped Flakes Robert Patten

Deciphering the behavioural heritage of knapped flakes Robert Patten Stone Dagger Publications. 10803 W. Connecticut Ave., Lakewood, CO, USA. Email: [email protected] Abstract: The major dimensions of a flake are shown to accurately capture how a knapper's actions manage the impact dynamics responsible for flake formation. When weight and density are also known, those same dimensions convey essential information about the volumetric geometry of a flake, including basic flake shapes typically valued for tools or to control core morphology. Combining the complementary modes of information allows the culturally imbedded heritage of a removed flake to be sufficiently represented that lithic analysts can reliably evaluate the mechanisms of flake formation without needing to be skilled flintknappers themselves. Presuming that habits of making flakes are culturally determined, it should be feasible to distinguish signature traits between lithic traditions. Keywords: flake morphology; knapping behaviour; impact dynamics; fracture mechanics 1. Introduction Flakes are the residue from one of humanities earliest technological advances and certainly its most persistent; in fact, the vast majority of archaeological evidence consists of flakes. Archaeologists routinely associate flakes and their scars with knapped tools presumed to be responsible for their creation but, unfortunately, there is no universal guide for interpreting the information available from flakes. Identifying for certain how a stone tool was made is complicated by the equifinality problem, referring to the difficulty in discerning the distinction between separate means of achieving the same result. There are three basic modes of archaeological flake manufacture: direct percussion, indirect percussion, and pressure. Each mode can be accomplished by myriad knapping tools and their capabilities are known to overlap considerably. -

When Metal Met Stone Searching for Traces of Metal Tool Utilization During the Production of Late Neolithic Nordic Flint Daggers

When Metal met Stone Searching for traces of metal tool utilization during the production of Late Neolithic Nordic Flint Daggers Gregory H. Strand Tanner Master’s Thesis in Archaeological Science Archaeological Research Laboratory Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies Stockholm University 2015 Supervisors: Kerstin Lidén Lena Holmquist 1 Abstract: This paper deals with the Late Neolithic Nordic Flint Daggers excavated from the gallery grave at Utbogården, Västergötland County, Sweden. Studies were undertaken in order to gain more understanding regarding the production processes and types of tools utilized during production/reduction, which can be assigned to certain specific, well preserved examples of these daggers. The results of these studies, in turn, will be able to shed light on the processes involved in producing Late Neolithic daggers in general, regardless of their individual states of preservation. This will be attempted by means of experimental flint knapping, comparative microscopic analysis, and chemical analysis. Acknowledgements: A special thanks is due to four individuals, for their aid in making this paper possible. In particular: Jackie Taffinder of the Swedish History Museum, for friendly advice, and making the Utbogården daggers freely available for non-destructive analysis, Kerstin Lidén and Lena Holmquist of Stockholm University for their supervision and support, and Sven Isaksson, also of Stockholm University for aid in the chemical analysis. Cover Image: SHM 5386: the daggers from Utbogården. (Photo by -

Flaked Stone Tool Patterning As a Means for Inferring Fremont Obsidian Procurement and Exchange

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title Flaked Stone Tool Patterning as a Means for Inferring Fremont Obsidian Procurement and Exchange Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8v9634v1 Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 28(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Authors Andrews, Bradford W. Greubel, Rand A. Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 28. Ilo. 1 (2008) | pp. 23-41 Flaked Stone Tool Patterning as a Means for Inferring Fremont Obsidian Procurement and Exchange BRADFORD W. ANDREWS Department of Anthropology, Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma,WA 98447-0003 RAND A. GREUBEL Alpine Archaeological Consultants, Inc., P.O. Box 2075, Montrose, CO 81402-2075 The Hunchback Shelter (42BE751), located in the southeastern Great Basin, yielded a considerable amount of data on the prehistoric use of the site. Located adjacent to the Wild Horse Canyon and Schoo Mine obsidian sources, evidence indicates that Hunchback Shelter functioned as a camp where Archaic to Formative (Fremont) knappers produced both bifaces and expedient flake cores. The intent of these procurement visits appears to have shifted over time. Furthermore, the Fremont visits appear to be consistent with comparative evidence from Five Finger Ridge, a major Fremont village. These findings have important implications for understanding the relationship between procurement behavior and settlement structure, and the relative importance ofbiface versus core technologies during the Fremont period. 0CATED IN THE SOUTHEASTERN Great Basin of residentiaUy mobile foragers to more logistically-based, 1^ Utah (Fig. 1), the Hunchback Sheher (42BE751) is semi-sedentary or sedentary forager/farmers. -

City of Hendersonville Construction Manual

City of Hendersonville Construction Manual SPECIFICATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS STANDARD DRAWINGS DRAINAGE STRUCTRES PAGE No. 4’ – 6’ Dia. Circular Manhole 1 Concrete Ditch Section 2 Pre-Cast Inlet 3 Ditch Section 4 Grass Ditch Section 5 Concrete Headwall 6 Junction Box Detail 7 Manhole / Inlet 8 EROSION CONTROL Check Dam 9 Construction Entrance 10 Inlet Protection 11 Rip-Rap 12 Silt Fence 13 Straw Bale Silt Barrier 14 STANDARD STREET SECTIONS Collector 15 Sub-collector 16 Lane 17 Place – Average Daily Traffic of 100 or less 18 Place – Average Daily Traffic of 100 or more 19 Extruded Concrete Curb Driveway Ramp 20 Roll Over Curb and Gutter for Places and Lanes Only 21 Standard Curb and Gutter 22 Handicapped Ramp Layout 23 Sidewalk 24 SECTION NO. AND TITLE PAGES 02050 Demolition 2 02110 Clearing and Grubbing 4 02210 Grading and Excavating 4 02215 Base and Subgrade Treatment 8 02221 Trenching, Backfilling, and Compaction 16 i 02250 Soil and Erosion Control 31 02271 Rip-Rap 4 02305 Jacking and Boring 3 02444 Chain Link Fences and Gates 3 02451 Guardrails 3 02452 Highway Signs 2 02485 Lawn and Grass Landscaping; Temporary Seeding 4 02486 Lawn and Grass Landscaping; Permanent Seeding 14 02490 Topsoil 3 02491 Sodding 3 02513 Asphalt Concrete Paving 19 02515 Portland Cement Concrete Paving 1 02528 Concrete Sidewalks, Curbs, and Gutters 8 02577 Pavement Marking 2 02721 Storm Drainage Systems 6 03001 Concrete Work 19 ii SECTION 02050 DEMOLITION PART 1 GENERAL 1.01 WORK INCLUDED A. Removal and disposal of designated foundations, pavements, concrete, bridges, culverts and other structures. -

Tool-Making Technology?

CTOOL-MAKINGHAPTER THREETECHNOLOGY STUDENTS LEARN HOW THE TIMUCUA USED NATURAL MATERIALS TO MAKE TOOLS - AND HOW THESE TOOLS HELPED THEM TO SURVIVE. WHAT IS TOOl-MAKING TECHNOLOGY? Except for a few animal species (including apes, crows, and elephants), humans are the only tool- makers on the planet. Every human culture creates and uses tools. Tool-making is more than simply picking up a sharp shell and using it to chop wood (that’s tool USE). Tool-making is the intentional creation of tools to solve problems. Interestingly, modern Floridians don’t spend much time making their own tools. If they need to chop down a tree, they buy an axe. Or they hire someone to chop the tree for them. If they had to make their own axe, they probably wouldn’t know where to start. In the modern world, work has become very specialized. Specific people do specific things. Most of our tools are not made by people at all. They’re made by machines. Life was very different in early Florida. There was little specialization. Every woman knew how to make pottery. Every man knew how to knap stone points. Everyone understood how to carve wood, bone, and antler. Everyone knew how to manufacture shell tools. They did not attend school to learn these skills. Instead, mothers and fathers, aunts and uncles, grandmothers and grandfathers made tools as daily life required, and the children observed and asked questions. Timucua kids were expected to master these tool-making skills as they approached adulthood, in the same way that modern kids are expected to learn to read, to swim, and to drive a car. -

Winchester Stone by Dr John Parker (PDF)

Winchester Stone by John Parker ©2016 Dr John Parker studied geology at Birmingham and Cambridge universities. He is a Fellow of the Geological Society of London. For over 30 years he worked as an exploration geologist for Shell around the world. He has lived in Winchester since 1987. On retirement he trained to be a Cathedral guide. The Building of Winchester Cathedral – model in the Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux 1 Contents Introduction page 3 Geological background 5 Summary of the stratigraphic succession 8 Building in Winchester Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon periods 11 Early medieval period (1066-1350) 12 Later medieval period (1350-1525) 18 16th to 18th century 23 19th to 21st century 24 Principal stone types 28 Chalk, clunch and flint 29 Oolite 30 Quarr 31 Caen 33 Purbeck 34 Beer 35 Upper Greensand 36 Portland 38 Other stones 40 Weldon 40 Chilmark 41 Doulting 41 French limestones 42 Coade Stone 42 Decorative stones, paving and monuments 43 Tournai Marble 43 Ledger stones and paving 44 Alabaster 45 Jerusalem stone 45 Choice of stone 46 Quarries 47 A personal postscript 48 Bibliography and References 50 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Photographs and diagrams are by the author, unless otherwise indicated 2 Introduction Winchester lies in an area virtually devoid of building stone. The city is on the southern edge of the South Downs, a pronounced upland area extending from Salisbury Plain in the west to Beachy Head in the east (Figs. 1 & 2). The bedrock of the Downs is the Upper Cretaceous Chalk (Fig. 3), a soft friable limestone unsuited for major building work, despite forming impressive cliffs along the Sussex coast to the east of Brighton. -

The Role of Experimental Knapping in Empirically Testing Key Themes in the Evolution of Lithic Technology: Reduction Intensity, Efficiency and Behavioural Complexity

The role of experimental knapping in empirically testing key themes in the evolution of lithic technology: reduction intensity, efficiency and behavioural complexity Antoine Muller BA (archaeology) BA Honours (archaeology) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2017 School of Social Science Abstract Experimental knapping has complimented and stimulated lithic analyses for over a century. Throughout this period, the discipline has witnessed an increase in the scientific rigour and theoretical grounding with which these studies are conducted. This thesis charts these key trends and in doing so establishes a best-practice model of experimental knapping, the veracity of which is in turn tested using four new lithic experiments. These case-studies employ experimental knapping to advance our understanding of flake platform measurement, reduction intensity, technological efficiency, and behavioural complexity. The first case-study, Chapter 3, offers a more accurate and precise calliper-based method of flake platform measurement that relies on simple geometric approximations of platform shape rather than the inflexible and unreliable existing method of multiplying platform width by thickness. In Chapter 4, a new reduction intensity metric for backed blades, a hitherto overlooked tool-type, is developed and tested on the backed blades from an early Neolithic site in Turkey. This new metric allows a reconstruction of the raw material consumption patterns at the site, finding that the backed blades likely contributed to conserving the inhabitants’ scarce lithic raw material. Meanwhile, Chapter 5 outlines the results of a comparison of the raw material efficiency of eight different lithic technologies, finding that lithic technological efficiency was a generally ascending trend over the last 3.3 million years and that the main transition in efficiency occurred between the Lower to Middle Palaeolithic. -

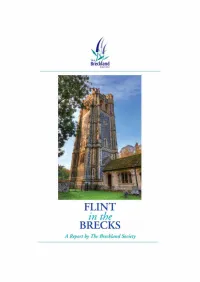

Flint in the Brecks WEB ONLY

©Text, layout and use of all images in this publication: The Breckland Society 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder. Text written by Anne Mason & James Parry. Editing by Liz Dittner. Front cover: The Church of St Andrew & St Patrick, Elveden. © Nick Ford. Designed by Duncan McLintock. Printed by SPC Printers Ltd, Thetford. Project trainees at one of the flintknapping workshops led by John Lord in November 2014. This report is dedicated to the memory of Dr Colin Pendleton (1952–2014), Senior Historic Environment Records Officer at Suffolk County Council, who shared his enthusiasm, knowledge and expertise so generously with the Breckland Society on this and other projects. FLINT IN THE BRECKS Contents Map of the Brecks . 4 Introduction . 5 1. Context and Background . 7 2. Flint in the Built Heritage of the Brecks . 10 3. The Gunflint Industry in the Brecks . 20 4. Social History and Legacy . 27 Appendix One: The Frank Norgate Diaries . 36 Appendix Two: The William Carter Flint Mosaics . 38 Bibliography and Credits . 40 A REPORT BY THE BRECKLAND SOCIETY FLINT IN THE BRECKS 4 A REPORT BY THE BRECKLAND SOCIETY FLINT IN THE BRECKS Introduction The Breckland Society was set up in 2003 to encourage interest and research into the natural, built and social heritage of the East Anglian Brecks. It is a membership organisation working to help protect the area and offering a range of activities to those who wish to see its special qualities preserved and enhanced. -

Appendix 4. Other Bibliography

EXARC Journal Let the Chips Fall Where They May: Evaluating the Impact and Effectiveness of Video Resources for Knowledge Transfer in Flint Knapping | John Kiernan (US) | Issue 2020/4 | Experimental Archaeology https://exarc.net/journal Appendix 4. Other Bibliography Internet Based Reference USAF Skill Levels – Available at: https://www.thebalancecareers.com/air-force-specialty-codes- 3344040. [Accessed 22 March 2019]. DVD Reference List 9 Step Knapping – Flintknapping Made Easy. 2011. [DVD] Starnater, E. Practical Primitive LLC. Basic Flintknapping Technique. 2007. [DVD] Collins, E. Washington, Mississippi: Native Way. Beyond Thrashing and Bashing – Flint Knapping : Next Steps. 2008. [DVD] Branson: Mound Builder Books. Caught Knapping. 1994. [DVD] Ratzatt, C. Quapaw, OK: Neolithics. Flint Knapping with Bruce Bradley PHD. 1989. [DVD] Bradley, B. INTERpark Inc., Cortez. Flintknapping featuring Clovis Technology. 2006. [DVD] Bradley, B. INTERpark Inc., Cortez. Flintknapping featuring Solutrean Technology with Bruce Bradley PHD. 2008. [DVD] Bradley, B. INTERpark Inc., Cortez. Flintknapping – The art of the ancients. 2004. [DVD] Blackwell, W. McLean design/Opposable Thumb Productions. Making a barbed and tanged arrowhead. 2004. [DVD] Lord, J. U.K. Making Danish Square-sectioned Axes with D.C. Waldorf . 2008. [DVD] Branson: Mound Builder Books. Making the Cahokia and Ishi points with Jim Redfern. 2006. [DVD] Redfern, J. Branson: Mound Builder Books. Making the Type IV Danish Dagger with D.C. Waldorf. 2007. [DVD] Waldorf, D.C. Branson: Mound Builder Books. Replicating the Type Ic Neolithic Danish Dagger – Advanced flintknapping with Greg Nunn. 2005. [DVD] Nunn, G. Castle Valley: Greg Nunn/Paleo Technologies. Understanding…Flintknapping Fundamentals. 2004. [DVD] Bracken, M. Bracken Bows Inc. On-line YouTube Videos Gregpryorhomestead, 2018. -

Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press

UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Title The Stones of Tiahuanaco Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2192r04f ISBN 978-1-931745-67-3 Authors Protzen, Jean-Pierre Nair, Stella Publication Date 2013-02-01 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are within the manuscript. Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California READ ONLY / NO DOWNLOAD ince Europeans first saw the monume of Lake Titicaca in Bolivia, they hav Sproduced them. These construction most artful and skillful stone architecture the point that writers from Spanish chron of the twentieth century have claimed that T a model for their architecture and stone m stonemasons from the Titicaca Basin to c study refutes this idea and delves into quest stonecutters; their knowledge of geometry the stone. The detailed analyses of building s of Tiahuanaco, including its appearance, rule MONOG Tiahuanaco_softcover.indd 1 12/17/12 12:10 PM READ ONLY / NO DOWNLOAD THE STONES OF TIAHUANACO READ ONLY / NO DOWNLOAD COTSEN INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY PRESS Monogr aph Series CONTRIBUTIONS IN FIELD RESEARCH AND CURRENT ISSUES IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL METHOD AND THEORY Monogr aph 74 Monogr aph 71 ROCK ART AT LITTLE LAKE: CRUCIBLE OF PUEBLOS: AN ANCIENT CROSSROADS IN THE EarlY PUEBLO PERIOD IN THE CalIFORNIA DESERT THE NORTHERN SOUTHWEST Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Gordon E. Hull, Richard H. Wilshusen, Gregson Schachner, and John C. Bretney and James R. Allison (eds.) Monogr aph 73 Monogr aph 70 THE HISTORY OF THE PEOplES CHOTUNA AND CHORNANCap: OF THE EASTERN DESERT EXCAVATING AN ANCIENT Hans Barnard and Kim Duistermaat (eds.) PERUVIAN LEGEND Christopher B.