5. WAGNER, SPARROW NEST DEFENSE, FFN 44(2).Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grasshopper Sparrow,Ammodramus Savannarum Pratensis

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Grasshopper Sparrow Ammodramus savannarum pratensis pratensis subspecies (Ammodramus savannarum pratensis) in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2013 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2013. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Grasshopper Sparrow pratensis subspecies Ammodramus savannarum pratensis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 36 pp. (www.registrelep- sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC acknowledges Carl Savignac for writing the status report on the Grasshopper Sparrow pratensis subspecies, Ammodramus savannarum pratensis in Canada, prepared with the financial support of Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Marty Leonard, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Bruant sauterelle de la sous- espèce de l’Est (Ammodramus savannarum pratensis) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Grasshopper Sparrow pratensis subspecies — photo by Jacques Bouvier. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014. Catalogue No. CW69-14/681-2014E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-23548-6 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – November 2013 Common name Grasshopper Sparrow - pratensis subspecies Scientific name Ammodramus savannarum pratensis Status Special Concern Reason for designation In Canada, this grassland bird is restricted to southern Ontario and southwestern Quebec. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Ammodramus Bairdii): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Baird’s Sparrow (Ammodramus bairdii): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project June 9, 2006 David A. Wiggins, Ph.D. Strix Ecological Research 1515 Classen Drive Oklahoma City, OK 73106 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Wiggins, D.A. (2006, June 9). Baird’s Sparrow (Ammodramus bairdii): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/ bairdssparrow.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Brenda Dale, Stephen Davis, Michael Green, and Stephanie Jones provided reprints and unpublished information on Baird’s sparrows – this assessment would not have been possible without their previous research work and helpful assistance. Greg Hayward and Gary Patton gave many useful tips for enhancing the structure and quality of this assessment. I also thank Rick Baydack, Scott Dieni, and Stephanie Jones for providing thorough reviews that greatly improved the quality of the assessment. AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHY David Wiggins developed an early interest in ornithology. During his high school years, he worked as a museum assistant under Gary Schnell and George Sutton at the University of Oklahoma. He later earned degrees from the University of Oklahoma (B.Sc. in Zoology), Brock University (M.Sc. - Parental care in Common Terns, under the supervision of Ralph Morris), and Simon Fraser University (Ph.D. - Selection on life history traits in Tree Swallows, under the supervision of Nico Verbeek). This was followed by a National Science Foundation Post-doctoral fellowship at Uppsala University in Sweden, where he studied life history evolution in Collared Flycatchers, and later a Fulbright Fellowship working on the reproductive ecology of tits (Paridae) in Namibia and Zimbabwe. -

21 Sep 2018 Lists of Victims and Hosts of the Parasitic

version: 21 Sep 2018 Lists of victims and hosts of the parasitic cowbirds (Molothrus). Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum Brood parasitism is an awkward term to describe an interaction between two species in which, as in predator-prey relationships, one species gains at the expense of the other. Brood parasites "prey" upon parental care. Victimized species usually have reduced breeding success, partly because of the additional cost of caring for alien eggs and young, and partly because of the behavior of brood parasites (both adults and young) which may directly and adversely affect the survival of the victim's own eggs or young. About 1% of all bird species, among 7 families, are brood parasites. The 5 species of brood parasitic “cowbirds” are currently all treated as members of the genus Molothrus. Host selection is an active process. Not all species co-occurring with brood parasites are equally likely to be selected nor are they of equal quality as hosts. Rather, to varying degrees, brood parasites are specialized for certain categories of hosts. Brood parasites may rely on a single host species to rear their young or may distribute their eggs among many species, seemingly without regard to any characteristics of potential hosts. Lists of species are not the best means to describe interactions between a brood parasitic species and its hosts. Such lists do not necessarily reflect the taxonomy used by the brood parasites themselves nor do they accurately reflect the complex interactions within bird communities (see Ortega 1998: 183-184). Host lists do, however, offer some insight into the process of host selection and do emphasize the wide variety of features than can impact on host selection. -

(AMMODRAMUS NELSONI) SPARROWS by Jennifer Walsh University of New Hampshire, September 2015

HYBRID ZONE DYNAMICS BETWEEN SALTMARSH (AMMODRAMUS CAUDACUTUS) AND NELSON’S (AMMODRAMUS NELSONI) SPARROWS BY JENNIFER WALSH Baccalaureate Degree (BS), University of New Hampshire, 2007 Master’s Degree (MS), University of New Hampshire, 2009 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Natural Resources and Environmental Studies September, 2015 This dissertation has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies in the Department of Natural Resources and Earth Systems Science by: Dissertation Director, Adrienne I. Kovach Research Associate Professor of Natural Resources Brian J. Olsen, Assistant Professor, School of Biology and Ecology, University of Maine W. Gregory Shriver, Associate Professor of Wildlife Ecology, University of Delaware Rebecca J. Rowe, Assistant Professor of Natural Resources Kimberly J. Babbitt, Professor of Natural Resources On July 9, 2015 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While pursuing my doctorate, a number of people have helped me along the way, and to each of them I am exceedingly grateful. First and foremost, I am grateful for my advisor, Adrienne Kovach, for her guidance, support, and mentorship. Without her, I would not be where I am, and I will be forever grateful for the invaluable role she has played in my academic development. Her unwavering enthusiasm for the project and dedication to its success has been a source of inspiration and I will never forget our countless road trips and long days out on the marsh. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Species Assessment for Baird's Sparrow (Ammodramus Bairdii) in Wyoming

SPECIES ASSESSMENT FOR BAIRD ’S SPARROW (AMMODRAMUS BAIRDII ) IN WYOMING prepared by 1 2 ROBERT LUCE AND DOUG KEINATH 1 P.O. Box 2095, Sierra Vista, Arizona 85636, [email protected] 2 Zoology Program Manager, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, 1000 E. University Ave, Dept. 3381, Laramie, Wyoming 82071; 307-766-3013; [email protected] prepared for United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Wyoming State Office Cheyenne, Wyoming December 2003 Luce and Keinath – Ammodramus bairdii December 2003 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 5 NATURAL HISTORY ........................................................................................................................... 6 Morphological Description..................................................................................................... 6 Identification ...................................................................................................................................6 Vocalization ....................................................................................................................................7 Taxonomy and Distribution ................................................................................................... 7 Taxonomy .......................................................................................................................................7 Distribution -

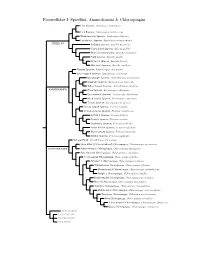

Passerellidae Species Tree

Passerellidae I: Spizellini, Ammodramini & Chlorospingini Lark Sparrow, Chondestes grammacus Lark Bunting, Calamospiza melanocorys Black-throated Sparrow, Amphispiza bilineata Five-striped Sparrow, Amphispiza quinquestriata SPIZELLINI Chipping Sparrow, Spizella passerina Clay-colored Sparrow, Spizella pallida Black-chinned Sparrow, Spizella atrogularis Field Sparrow, Spizella pusilla Brewer’s Sparrow, Spizella breweri Worthen’s Sparrow, Spizella wortheni Tumbes Sparrow, Rhynchospiza stolzmanni Stripe-capped Sparrow, Rhynchospiza strigiceps Grasshopper Sparrow, Ammodramus savannarum Grassland Sparrow, Ammodramus humeralis Yellow-browed Sparrow, Ammodramus aurifrons AMMODRAMINI Olive Sparrow, Arremonops rufivirgatus Green-backed Sparrow, Arremonops chloronotus Black-striped Sparrow, Arremonops conirostris Tocuyo Sparrow, Arremonops tocuyensis Rufous-winged Sparrow, Peucaea carpalis Cinnamon-tailed Sparrow, Peucaea sumichrasti Botteri’s Sparrow, Peucaea botterii Cassin’s Sparrow, Peucaea cassinii Bachman’s Sparrow, Peucaea aestivalis Stripe-headed Sparrow, Peucaea ruficauda Black-chested Sparrow, Peucaea humeralis Bridled Sparrow, Peucaea mystacalis Tanager Finch, Oreothraupis arremonops Short-billed (Yellow-whiskered) Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus parvirostris CHLOROSPINGINI Yellow-throated Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus flavigularis Ashy-throated Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus canigularis Sooty-capped Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus pileatus Wetmore’s Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus wetmorei White-fronted Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus albifrons Brown-headed -

Florida Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus Savannarum Floridanus) Conspecific Attraction Experiment

FLORIDA GRASSHOPPER SPARROW (AMMODRAMUS SAVANNARUM FLORIDANUS) CONSPECIFIC ATTRACTION EXPERIMENT THOMAS VIRZI ECOSTUDIES INSTITUTE P.O. BOX 735 EAST OLYMPIA, WA 98540 [email protected] REPORT TO THE U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE (SOUTH FLORIDA ECOLOGICAL SERVICES, VERO BEACH, FL) AND THE FISH & WILDLIFE FOUNDATION OF FLORIDA (TALLAHASSEE, FL) DECEMBER 2015 Contents 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 PURPOSE ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 3.0 PLAYBACK EXPERIMENT .......................................................................................................................... 13 3.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................ 13 3.2 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................................... 13 3.3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ............................................................................................................................... -

Captive Wildlife Regulations, 2021, W-13.12 Reg 5

1 CAPTIVE WILDLIFE, 2021 W-13.12 REG 5 The Captive Wildlife Regulations, 2021 being Chapter W-13.12 Reg 5 (effective June 1, 2021). NOTE: This consolidation is not official. Amendments have been incorporated for convenience of reference and the original statutes and regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpretation and application of the law. In order to preserve the integrity of the original statutes and regulations, errors that may have appeared are reproduced in this consolidation. 2 W-13.12 REG 5 CAPTIVE WILDLIFE, 2021 Table of Contents PART 1 PART 5 Preliminary Matters Zoo Licences and Travelling Zoo Licences 1 Title 38 Definition for Part 2 Definitions and interpretation 39 CAZA standards 3 Application 40 Requirements – zoo licence or travelling zoo licence PART 2 41 Breeding and release Designations, Prohibitions and Licences PART 6 4 Captive wildlife – designations Wildlife Rehabilitation Licences 5 Prohibition – holding unlisted species in captivity 42 Definitions for Part 6 Prohibition – holding restricted species in captivity 43 Standards for wildlife rehabilitation 7 Captive wildlife licences 44 No property acquired in wildlife held for 8 Licence not required rehabilitation 9 Application for captive wildlife licence 45 Requirements – wildlife rehabilitation licence 10 Renewal 46 Restrictions – wildlife not to be rehabilitated 11 Issuance or renewal of licence on terms and conditions 47 Wildlife rehabilitation practices 12 Licence or renewal term PART 7 Scientific Research Licences 13 Amendment, suspension, -

Conservation Assessment—Henslow's

United States Department of Conservation Agriculture Forest Service Assessment—Henslow’s North Central Sparrow Ammodramus Research Station General Technical henslowii Report NC-226 Dirk E. Burhans The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Front cover Henslow’s Sparrow photograph: ©Doug Wechsler/VIREO. Published by: North Central Research Station Forest Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 1992 Folwell Avenue St. Paul, MN 55108 2002 Web site: www.ncrs.fs.fed.us TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ............................................................................................... 3 TAXONOMY......................................................................................................................................... -

CONSERVATION GENETICS of the FLORIDA GRASSHOPPER SPARROW (Ammodramus Savannarum Floridanus)

CONSERVATION GENETICS OF THE FLORIDA GRASSHOPPER SPARROW (Ammodramus savannarum floridanus) By NATALIE LYNNETTE BULGIN, B.Sc. A Thesis Submitted to the School ofGraduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Master of Science McMaster University © Copyright by Natalie Lynnette Bulgin, September 2000 MASTER OF SCIENCE (2000) McMaster University (Biology) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Conservation Genetics ofthe Florida Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum floridmms) AUTHOR:NatalieBlliWn SUPERVISOR: Dr. H.L. Gibbs NUMBER OF PAGES: x, 138 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my supervisor, Dr. H. Lisle Gibbs for his time, patience, and commitment to my transition from a naive undergraduate geneticist to a less, but still slightly naive, molecular ecologist. I also thank my committee members, Drs. Bradley N. White and Susan A. Dudley, for stimulating discussion and suggestions regarding my thesis and science in general. I am grateful to our collaborator, Dr. Peter D. Vickery, for organizing the project, for insight into the biology ofthe species, and for making me realize I am not as much ofa naturalist as I once tended to believe. Also, I thank Dr. Allan J. Baker, Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Biology at the University of Toronto for the use ofhis automated sequencer, and technical and analytical support. Also, I thank Dr. John C. Avise for donating purified mtDNA from various Ammodramus species. I am grateful to Dr. Brian Golding and Liisa Koski for assistance with the phylogenetic analyses. My utmost appreciation goes to Tylan Dean and Dusty Perkins for collection of Grasshopper Sparrow blood samples throughout the United States - God and Bonnie know I couldn't have done it.