The Ghost of the Sage of Highgate Richard Haven University of Massachusetts Ta Amherst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Our Student Guide for Over-18S

St Giles International London Highgate, 51 Shepherds Hill, Highgate, London N6 5QP Tel. +44 (0) 2083400828 E: [email protected] ST GILES GUIDE FOR STUDENTS AGED 18 LONDON IGHGATE AND OVER H Contents Part 1: St Giles London Highgate ......................................................................................................... 3 General Information ............................................................................................................................. 3 On your first day… ............................................................................................................................... 3 Timetable of Lessons ............................................................................................................................ 4 The London Highgate Team ................................................................................................................. 5 Map of the College ............................................................................................................................... 6 Courses and Tests ................................................................................................................................. 8 Self-Access ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Rules and Expectations ...................................................................................................................... 10 College Facilities ............................................................................................................................... -

Buses from Finchley South 326 Barnet N20 Spires Shopping Centre Barnet Church BARNET High Barnet

Buses from Finchley South 326 Barnet N20 Spires Shopping Centre Barnet Church BARNET High Barnet Barnet Underhill Hail & Ride section Great North Road Dollis Valley Way Barnet Odeon New Barnet Great North Road New Barnet Dinsdale Gardens East Barnet Sainsburys Longmore Avenue Route finder Great North Road Lyonsdown Road Whetstone High Road Whetstone Day buses *ULIÀQ for Totteridge & Whetstone Bus route Towards Bus stops Totteridge & Whetstone North Finchley High Road Totteridge Lane Hail & Ride section 82 North Finchley c d TOTTERIDGE Longland Drive 82 Woodside Park 460 Victoria a l Northiam N13 Woodside i j k Sussex Ring North Finchley 143 Archway Tally Ho Corner West Finchley Ballards Lane Brent Cross e f g l Woodberry Grove Ballards Lane 326 Barnet i j k Nether Street Granville Road NORTH FINCHLEY Ballards Lane Brent Cross e f g l Essex Park Finchley Central Ballards Lane North Finchley c d Regents Park Road Long Lane 460 The yellow tinted area includes every Dollis Park bus stop up to about one-and-a-half Regents Park Road Long Lane Willesden a l miles from Finchley South. Main stops Ballards Lane Hendon Lane Long Lane are shown in the white area outside. Vines Avenue Night buses Squires Lane HE ND Long Lane ON A Bus route Towards Bus stops VE GR k SP ST. MARY’S A EN VENUE A C V Hail & Ride section E E j L R HILL l C Avenue D L Manor View Aldwych a l R N13 CYPRUS AVENUE H House T e E R N f O Grounds East Finchley East End Road A W S m L E c d B A East End Road Cemetery Trinity Avenue North Finchley N I ` ST B E O d NT D R D O WINDSOR -

Life Expectancy

HEALTH & WELLBEING Highgate November 2013 Life expectancy Longer lives and preventable deaths Life expectancy has been increasing in Camden and Camden England Camden women now live longer lives compared to the England average. Men in Camden have similar life expectancies compared to men across England2010-12. Despite these improvements, there are marked inequalities in life expectancy: the most deprived in 80.5 85.4 79.2 83.0 Camden will live for 11.6 (men) and 6.2 (women) fewer years years years years years than the least deprived in Camden2006-10. 2006-10 Men Women Belsize Longer life Hampstead Town Highgate expectancy Fortune Green Swiss Cottage Frognal and Fitzjohns Camden Town with Primrose Hill St Pancras and Somers Town Hampstead Town Camden Town with Primrose Hill Fortune Green Swiss Cottage Frognal and Fitzjohns Belsize West Hampstead Regent's Park Bloomsbury Cantelowes King's Cross Holborn and Covent Garden Camden Camden Haverstock average2006-10 average2006-10 Gospel Oak St Pancras and Somers Town Highgate Cantelowes England England Haverstock 2006-10 Holborn and Covent Garden average average2006-10 West Hampstead Regent's Park King's Cross Gospel Oak Bloomsbury Shorter life Kentish Town Kentish Town expectancy Kilburn Kilburn Note: Life expectancy data for 70 72 74 76 78 80 82 84 86 88 90 90 88 86 84 82 80 78 76 74 72 70 wards are not available for 2010-12. Life expectancy at birth (years) Life expectancy at birth (years) About 50 Highgate residents die Since 2002-06, life expectancy has Cancer is the main cause of each year2009-11. -

Verse in Fraser's Magazine

Curran Index - Table of Contents Listing Fraser's Magazine For a general introduction to Fraser's Magazine see the Wellesley Index, Volume II, pages 303-521. Poetry was not included in the original Wellesley Index, an absence lamented by Linda Hughes in her influential article, "What the Wellesley Index Left Out: Why Poetry Matters to Periodical Studies," Victorian Periodicals Review, 40 (2007), 91-125. As Professor Hughes notes, Eileen Curran was the first to attempt to remedy this situation in “Verse in Bentley’s Miscellany vols. 1-36,” VPR 32 (1999), 103-159. As one part of a wider effort on the part of several scholars to fill these gaps in Victorian periodical bibliography and attribution, the Curran Index includes a listing of verse published in Fraser's Magazine from 1831 to 1854. EDITORS: Correct typo, 2:315, 1st line under this heading: Maginn, if he was editor, held the office from February 1830, the first issue, not from 1800. [12/07] Volume 1, Feb 1830 FM 3a, A Scene from the Deluge (from the German of Gesner), 24-27, John Abraham Heraud. Signed. Verse. (03/15) FM 4a, The Standard-Bearer -- A Ballad from the Spanish, 38-39, John Gibson Lockhart. possib. Attributed by Mackenzie in introduction to Fraserian Papers Vol I; see Thrall, Rebellious Fraser: 287 Verse. (03/15) FM 4b, From the Arabic, 39, Unknown. Verse. (03/15) FM 5a, Posthumous Renown, 44-45, Unknown. Verse. (03/15) FM 6a, The Fallen Chief (Translated from the Arabic), 54-56, Unknown. Verse. (03/15) Volume 1, Mar 1830 FM 16b, A Hard Hit for a Damosell, 144, Unknown. -

2021 First Teams - Premier Division Fixtures

2021 First Teams - Premier Division Fixtures Brondesbury vs. North Middlesex North Middlesex vs. Brondesbury Sat. 8 May Richmond vs. Twickenham Sat. 10 July Twickenham vs. Richmond Overs games Teddington vs. Ealing Time games Ealing vs. Teddington 12.00 starts Crouch End vs. Shepherds Bush 11.00 starts Shepherds Bush vs. Crouch End Finchley vs. Hampstead Hampstead vs. Finchley Shepherds Bush vs. Richmond Richmond vs. Shepherds Bush Sat. 15 May Ealing vs. Brondesbury Sat. 17 July Brondesbury vs. Ealing Overs games North Middlesex vs. Finchley Time games Finchley vs. North Middlesex 12.00 starts Twickenham vs. Teddington 11.00 starts Teddington vs. Twickenham Hampstead vs. Crouch End Crouch End vs. Hampstead Brondesbury vs. Teddington Teddington vs. Brondesbury Sat. 22 May Richmond vs. Hampstead Sat. 24 July Hampstead vs. Richmond Overs games Crouch End vs. North Middlesex Time games North Middlesex vs. Crouch End 12.00 starts Finchley vs. Ealing 11.00 starts Ealing vs. Finchley Twickenham vs. Shepherds Bush Shepherds Bush vs. Twickenham Brondesbury vs. Finchley Finchley vs. Brondesbury Sat. 29 May Teddington vs. Shepherds Bush Sat. 31 July Shepherds Bush vs. Teddington Overs games Ealing vs. Crouch End Time games Crouch End vs. Ealing 12.00 starts North Middlesex vs. Richmond 11.00 starts Richmond vs. North Middlesex Hampstead vs. Twickenham Twickenham vs. Hampstead Richmond vs. Ealing Ealing vs. Richmond Sat. 5 June Shepherds Bush vs. Hampstead Sat. 7 August Hampstead vs. Shepherds Bush Overs games Crouch End vs. Brondesbury Time games Brondesbury vs. Crouch End 12.00 starts Finchley vs. Teddington 11.00 starts Teddington vs. Finchley Twickenham vs. -

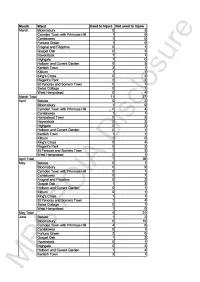

Month Ward Used to Injure Not Used to Injure March Bloomsbury 0 3

Month Ward Used to Injure Not used to injure March Bloomsbury 0 3 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 1 5 Cantelowes 1 0 Fortune Green 1 0 Frognal and Fitz'ohns 0 1 Gospel Oak 0 2 Haverstock 1 1 Highgate 1 0 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 3 Kentish Town 3 1 Kilburn 1 1 King's Cross 0 2 Regent's Park 2 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 0 1 Swiss Cottage 0 1 West Hampstead 0 4 March Total 11 27 April Belsize 0 2 Bloomsbury 1 9 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 0 4 Cantelowes 1 1 Hampstead Town 0 2 Haverstock 2 3 Highgate 0 3 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 1 Kentish Town 1 1 Kilburn 1 0 King's Cross 0 4 Regent's Park 0 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 3 West Hampstead 0 1 April Total 7 36 May Belsize 0 1 Bloomsbury 0 9 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 0 1 Cantelowes 0 7 Frognal and Fitzjohns 0 2 Gospel Oak 1 3 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 1 Kilburn 0 1 King's Cross 1 1 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 4 Swiss Cottage 0 1 West Hampstead 1 0 May Total 4 31 June Belsize 1 2 Bloomsbury 0 1 0 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 4 6 Cantelowes 0 1 Fortune Green 2 0 Gospel Oak 1 3 Haverstock 0 1 Highgate 0 2 Holborn and Covent Garden 1 4 Kentish Town 3 1 MPS FOIA Disclosure Kilburn 2 1 King's Cross 1 1 Regent's Park 2 1 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 3 Swiss Cottage 0 2 West Hampstead 0 1 June Total 18 39 July Bloomsbury 0 6 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 5 1 Cantelowes 1 3 Frognal and Fitz'ohns 0 2 Gospel Oak 2 0 Haverstock 0 1 Highgate 0 4 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 3 Kentish Town 1 0 King's Cross 0 3 Regent's Park 1 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 0 Swiss Cottage 1 2 West -

Swiss Cottage

Swiss Cottage Population: 16,297 Land area: 115.615 hectares December 2015 The maps contained in this document are used under licence A-Z: Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright and database rights OS 100017302 OS: © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OS 100019726 Strengths Social 90.5% of the population do not have a disability or long term health problem (Camden: 85.6%) Economic 71.6% of residents are economically active (Camden: 68.1%) Average annual household income is £60,211 (Camden: £52,962) Significant retail presence Swiss Cottage has a designated town centre Health & Well-being 49% of adults eat healthily (Camden: 41.6%) Knowledge, Skills & Experience 64% of pupils achieved KS4 GCSE 5+ A*-C inc English & maths (Camden: 59.9%) Community Significantly lower total crime rate than the Camden average: 70 (Camden: 124.4) Challenges Social Population density of 141 people per hectare (Camden: 105.4pph) Economic There are 0.7 jobs per capita of working age residents (Camden: 2.1 jobs per capita) The lowest average annual household income is £32,141 (S. Cottage: £60,211; Camden: £52,962 Very little childcare provision - 0.05 places per capita of children under 5 (Camden: 0.27 places) Health & Wellbeing 16% or reception class primary school children are overweight (Camden: 12%) Community Only 64.6% of under 5s are registered with Early Years (Camden: 79%) Multiple deprivation Lower super output areas* that fall within 10% most deprived in England (S. Cottage = 10 LSOAs) Income deprivation (1 LSOA) Health and disability deprivation (5 LSOAs) Living environment deprivation (3 LSOAs) Income deprivation affecting children (1 LSOA) Income deprivation affecting older people (1 LSOA) * A lower super output area is a geography for the collection and publication of small area statistics. -

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and Their Origins

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and their origins © David A. Hayes and Camden History Society, 2020 Introduction Listed alphabetically are In 1853, in London as a whole, there were o all present-day street names in, or partly 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria, 37 King, 27 Queen, within, the London Borough of Camden 22 Princes, 17 Duke, 34 York and 23 Gloucester (created in 1965); Streets; not to mention the countless similarly named Places, Roads, Squares, Terraces, Lanes, o abolished names of streets, terraces, Walks, Courts, Alleys, Mews, Yards, Rents, Rows, alleyways, courts, yards and mews, which Gardens and Buildings. have existed since c.1800 in the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn and St Encouraged by the General Post Office, a street Pancras (formed in 1900) or the civil renaming scheme was started in 1857 by the parishes they replaced; newly-formed Metropolitan Board of Works o some named footpaths. (MBW), and administered by its ‘Street Nomenclature Office’. The project was continued Under each heading, extant street names are after 1889 under its successor body, the London itemised first, in bold face. These are followed, in County Council (LCC), with a final spate of name normal type, by names superseded through changes in 1936-39. renaming, and those of wholly vanished streets. Key to symbols used: The naming of streets → renamed as …, with the new name ← renamed from …, with the old Early street names would be chosen by the name and year of renaming if known developer or builder, or the owner of the land. Since the mid-19th century, names have required Many roads were initially lined by individually local-authority approval, initially from parish named Terraces, Rows or Places, with houses Vestries, and then from the Metropolitan Board of numbered within them. -

The Life of John Sterling

The Life of John Sterling Thomas Carlyle The Life of John Sterling Table of Contents The Life of John Sterling..........................................................................................................................................1 Thomas Carlyle..............................................................................................................................................1 PART I...........................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTORY..................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER II. BIRTH AND PARENTAGE.................................................................................................3 CHAPTER III. SCHOOLS: LLANBLETHIAN; PARIS; LONDON...........................................................6 CHAPTER IV. UNIVERSITIES: GLASGOW; CAMBRIDGE.................................................................13 CHAPTER V. A PROFESSION..................................................................................................................16 CHAPTER VI. LITERATURE: THE ATHENAEUM...............................................................................18 CHAPTER VII. REGENT STREET...........................................................................................................19 CHAPTER VIII. COLERIDGE...................................................................................................................22 -

Kentish Town Nw5

KENTISH TOWN NW5 A COLLECTION OF CREATIVE WORKSPACES IN A CHARACTERFUL BUILDING É SPACE FLEXIBLE ON-SITE CAF CYCLE STORAGE PURE GYM Work wonders Highgate Studios is a character Victorian warehouse building and home to the former Sanderson wallpaper factory. It has since been transformed into an inspiring collection of contemporary workspaces and studios, creating a flourishing campus community incorporating a wide variety of businesses. These include media, communications and manufacturing. The studios offer space with exceptional character, including high ceilings and excellent natural light, there is also an on-site café as well as plentiful breakout spaces that can provide additional areas for work with communal wi-fi. CREATIVE WORKSPACES WITH PERIOD FEATURES LOCATED WITHIN A FORMER VICTORIAN WALLPAPER FACTORY Perfectly placed Above all the intention has been to create a great place to work, spaces that can support business both large and small and amenities to support the wellbeing of staff. There is a managment team on-site as well as INTRODUCING NEVER FOR EVER: 24 hour security and parking by separate arrangement. There is both an on-site gym (Pure Gym) and nursery. AN EXCITING BREWERY STYLE The café serves hot food and beverages throughout the day and seating is offered inside or outside in BAR WITH WOOD FIRED PIZZA the newly designed courtyard, a peaceful area with abundant planting and striking artwork. AND LIVE MUSIC A new neighbourhood local has also opened at Highgate Studios; Never for Ever. Open throughout the week offering wood-fired pizzas, sharing boards, inventive small plates and lunch time specials, both to eat in or take away. -

Of the CAMDEN HISTORY SOCIETY No 141 Jan 1994 Under the Streets

No 141 of the CAMDEN HISTORY SOCIETY Jan 1994 of the project. These may be obtained from The Under the Streets of Camden Friends of St Pancras Housing, Freepost, 90 Eversholt Thurs 27 January, 7.30pm Street NWl 1YB. The poster cos ts £4. 99 and the cards St Pancras Church Hall, Lancing Street NWl (opposite (pack of 6) £5.49 (please add £1 for postage and Eversholt Street entrance to Euston Station) packing). There is always, it seems, an avid interest in what is beneath our streets - books such as The Lost Rivers of BURGH HOUSE HAPPENINGS London and London Under London have had remark- From 8 January to 23 March an exhibition will be at able sales. We are therefore confident that members BurghHousefeaturingdrawings, paintings,clayworks will find fascinating this talk by Dougald Gonsal, and photographs of Hampstead by children 10-12 Chief Engineer for the London Borough of Camden, years old at King Alfred's School who have studied on what there is beneath the streets of Camden, the area. In addition, Hampstead childhoods will be information gathered during his thirty years working remembered with old toys, scrapbooks and other in the area. A trip through some of the sewers is mementoes belonging to the Camden Local Studies promised but wellies are not required. Library and the Hampstead Museum. On 18 February Christopher Wade will be repeating Framing Opinions his popular Streets of Hampstead talk N o.1 at 2.30pm Tues 15th February, 7:30pm Gospel Oak Methodist Church, Lisburne Road, NW3. Rewriting Primrose Hill Our talk in February describes the ways in which the traditional details of our houses and other buildings As members may know we are revising our success- may be renovated and protected. -

Alexandra Palace to Tottenham Hale Walk

Saturday Walkers Club www.walkingclub.org.uk Alexandra Palace to Tottenham Hale walk Alexandra Palace, the Parkland Walk (a former railway line), two restored Wetlands and several cafés in north London Length Main Walk: 15¾ km (9.8 miles). Three hours 45 minutes walking time. For the whole excursion including trains, sights and meals, allow at least 7 hours. Short Walk 1, from Highgate: 11½ km (7.1 miles). Two hours 35 minutes walking time. Short Walk 2, to Manor House: 11½ km (7.1 miles). Two hours 45 minutes walking time. OS Map Explorer 173. Alexandra Palace is in north London, 10 km N of Westminster. Toughness 3 out of 10 (2 for the short walks from Alexandra Palace, 1 for the others). Features This walk is essentially a merger of two short walks. The first part is the popular Parkland Walk, a linear nature reserve created along the trackbed of a disused railway line. The second part links two new nature reserves created from operational Thames Water reservoirs, using a waymarked cycle/pedestrian route along residential streets. The walk starts with a short climb through Alexandra Park to Alexandra Palace, with splendid views of the London skyline from its terrace. This entertainment venue was intended as the north London counterpart to the Crystal Palace and although it was destroyed by fire just two weeks after opening in 1873 it was promptly rebuilt. Its private owners tried to sell the site and parkland for development in 1900 but it was acquired by a group of local authorities for the benefit of the public.