Britain Jazz Women Chapter Catherine P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

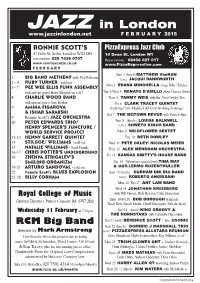

JAZZ in London F E B R U a R Y 2015

JAZZ in London www.jazzinlondon.net F E B R U A R Y 2015 RONNIE SCOTT’S PizzaExpress Jazz Club 47 Frith St. Soho, London W1D 4HT 10 Dean St. London W1 reservations: 020 7439 0747 Reservations: 08456 027 017 www.ronniescotts.co.uk www.PizzaExpresslive.com F E B R U A R Y Sun 1 (lunch) MATTHEW VanKAN with Phil Robson 1 BIG BAND METHENY (eve) JACQUI DANKWORTH 2 - 4 RUBY TURNER - sold out Mon 2 sings Billie Holiday 5 - 7 PEE WEE ELLIS FUNK ASSEMBLY EDANA MINGHELLA with special guest Huey Morgan on 6 & 7 Tue 3/Wed 4 RENATO D’AIELLO plays Horace Silver 8 CHARLIE WOOD BAND Thur 5 TAMMY WEIS with the Tom Cawley Trio with special guest Guy Barker Fri 6 CLARK TRACEY QUINTET 9 AMINA FIGAROVA featuring Chris Maddock & Henry Armburg-Jennings & ISHAR SARABSKI Sat 7 THE MOTOWN REVUE with Patrick Alan 9 Ronnie Scott’s JAZZ ORCHESTRA 10 PETER EDWARDS TRIO/ Sun 8 (lunch) LOUISE BALKWILL (eve) HENRY SPENCER’S JUNCTURE / SOWETO KINCH BAND WORLD SERVICE PROJECT Mon 9 WILDFLOWER SEXTET 11- 13 KENNY GARRETT QUINTET Tue 10 BETH ROWLEY 14 STILGOE/ WILLIAMS - sold out Wed 11 PETE OXLEY/ NICOLAS MEIER 15 - Soul Family NATALIE WILLIAMS Thur 12 ALEX MENDHAM ORCHESTRA 16-17 CHRIS POTTER’S UNDERGROUND Fri 13 18 ZHENYA STRIGALEV’S KANSAS SMITTY’S HOUSE BAND SMILING ORGANIZM Sat 14 Valentine’s special with TINA MAY 19-21 ARTURO SANDOVAL - sold out & GUILLERMO ROZENTHULLER 22 Ronnie Scott’s BLUES EXPLOSION Sun 15 (lunch) DURHAM UNI BIG BAND 23-28 BILLY COBHAM (eve) ROBERTO ANGRISANI Mon 16/ Tue17 ANT LAW BAND Wed 18 JONATHAN KREISBERG Royal College of Music with Will Vinson, Rick Rosato, Colin Stranahan (Britten Theatre) Prince Consort Rd. -

Ronnie Scott's Jazz C

GIVE SOMEONE THE GIFT OF JAZZ THIS CHRISTMAS b u l C 7 z 1 0 z 2 a r J MEMBERSHIP TO e b s ’ m t t e c o e c D / S r e e i GO TO: WWW.RONNIESCOTTS.CO.UK b n OR CALL: 020 74390747 m e n v o Europe’s Premier Jazz Club in the heart of Soho, London o N R Cover artist: Roberto Fonseca (Mon 27th - Wed 29th Nov) Page 36 Page 01 Artists at a Glance Wed 1st - Thurs 2nd: The Yellowjackets N LD OUT Wed 1st: Late Late Show Special - Too Many Zooz SO o Fri 3rd: Jeff Lorber Fusion v Sat 4th: Ben Sidran e m Sun 5th Lunch Jazz: Jitter Kings b Sun 5th: Dean Brown Band e Mon 6th - Tues 7th: Joe Lovano Classic Quartet r Wed 8th: Ronnie Scott’s Gala Charity Night feat. Curtis Stigers + Special Guests Thurs 9th: Marius Neset Quintet Fri 10th - Sat 11th: Manu Dibango & The Soul Makossa Gang Sun 12th Lunch Jazz: Salena Jones “Jazz Doyenne” Sun 12th: Matthew Stevens Preverbal November and December are the busiest times Mon 13th - Tues 14th: Mark Guiliana Jazz Quartet of the year here at the club, although it has to be Wed 15th - Thurs 16th: Becca Stevens Fri 17th - Sat 18th: Mike Stern / Dave Weckl Band feat. Tom Kennedy & Bob Malach UT said there is no time when we seem to slow down. Sun 19th Lunch Jazz: Jivin’ Miss Daisy feat. Liz Fletcher SOLD O November this year brings our Fundraising night Sun 19th: Jazzmeia Horn Sun 19th: Ezra Collective + Kokoroko + Thris Tian (Venue: Islington Assembly Hall) for the Ronnie Scott’s Charitable Foundation on Mon 20th - Tues 21st: Simon Phillips with Protocol IV November 8th featuring the Curtis Stigers Sinatra Wed 22nd: An Evening of Gershwin feat. -

The History of Women in Jazz in Britain

The history of jazz in Britain has been scrutinised in notable publications including Parsonage (2005) The Evolution of Jazz in Britain, 1880-1935 , McKay (2005) Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain , Simons (2006) Black British Swing and Moore (forthcoming 2007) Inside British Jazz . This body of literature provides a useful basis for specific consideration of the role of women in British jazz. This area is almost completely unresearched but notable exceptions to this trend include Jen Wilson’s work (in her dissertation entitled Syncopated Ladies: British Jazzwomen 1880-1995 and their Influence on Popular Culture ) and George McKay’s chapter ‘From “Male Music” to Feminist Improvising’ in Circular Breathing . Therefore, this chapter will provide a necessarily selective overview of British women in jazz, and offer some limited exploration of the critical issues raised. It is hoped that this will provide a stimulus for more detailed research in the future. Any consideration of this topic must necessarily foreground Ivy Benson 1, who played a fundamental role in encouraging and inspiring female jazz musicians in Britain through her various ‘all-girl’ bands. Benson was born in Yorkshire in 1913 and learned the piano from the age of five. She was something of a child prodigy, performing on Children’s Hour for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) at the age of nine. She also appeared under the name of ‘Baby Benson’ at Working Men’s Clubs (private social clubs founded in the nineteenth century in industrial areas of Great Britain, particularly in the North, with the aim of providing recreation and education for working class men and their families). -

Appendix 1 Periodicals of Interest to the Television Teacher

Appendix 1 Periodicals of Interest to the Television Teacher Broadcast The broadcasting industry's weekly magazine. Up-to-the-minute news, information, rumour and gossip with useful longer critical articles. An invaluable source for the teacher wishing to keep abreast or even ahead of current developments in broadcasting. (lllA Wardour Street, London Wl) Independent Broadcasting Quarterly journal of the Independent Broadcasting Authority. Occasionally carries articles of interest both on programmes and educational developments. (Free from the IBA, 70 Brompton Road, London SW3) Journal of the Centre for Advanced TV Studies Contains abstracts and reviews of recent books on television. (48 Theobalds Road, London, WCl 8NW) Journal ofEducational Television Journal of the Educational Television Association. Mainly devoted to educational technology but an increasing number of articles discuss the place of television within the curriculum. (80 Micklegate, York) The Listener Published weekly by the BBC. Contains transcripts of programmes and background articles on broadcasting. Media, Culture and Society A new journal published by the Polytechnic of Central London (309 Regent Street, London Wl) Media Reporter Quarterly journal, mainly devoted to journalism, but also carrying articles on media education. (Brennan Publications, 148 Birchover Way, Allestree, Derby) Media Studies Association Newsletter Contains conference reports, articles, news and reviews relating to media education. (Forster Building, Sunderland Polytechnic, Sunderland) Screen Quarterly. Mainly devoted to film, but there are occasionally critical articles on television. Screen Education Quarterly. Aimed specifically at media teachers and the most useful journal currently available for television teachers. Both Screen and Screen Education are published by the Society for Education in Film and Television. -

Sax Discrimination

%x Discrimination Number42 October 20, 1980 The last time I bent Current Con- whom [ spoke at the Congress could ten (s m readers’ collective ear to discuss understand why 1 wanted to do such an my love for the saxophone, I I said 1 had article. If 1 was at a scientific meeting never encountered a commercial record- and said [ was writing an article about ing by a woman saxophone player. A women scientists, there would be a high few readers wrote to me [o remedy this degree of interes[. [ would get a variety situation. A subsequent investigation of strong opinions on the subject of sex showed that there are relatively few discrimination in science. The lack of in- women sax players. However, we were terest on the part of the women sax- able to compile a brief list of recording~ ophone players indica[ed to me that made by women $axophonis[s. It ap- many in the world of music feel a musi- pears in Table 1. cian’s gender is irrelevant. Those women The paucity of’ women sax player~ 1spoke with at the WSC seemed to think raises the touchy question of sex dis- that if a woman had talent, she had no crimination. It is true that some of the problems in competing succe~sfully with greats of jazz are women. Ho}vever, ac- her male counterparts. But as we cording to some of the female saxi$ts we learned, not all women saxophonists feel spoke with, some forms of musical ex- this way. pression were considered “unladylike” One $tatement most women saxists for many years. -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'. -

The Sussex JAZZ MAG Monday 11Th - Sunday 24Th November 2013 CONTENTS Click Or Touch the Blue Links to Go to That Page

The Sussex AZZ MAG JFortnightly Issue 6 Monday 11th - Sunday 24th November 2013 Big Band Special Drummer Dave Trigwell with trombonists Tarik Mecci and Mark Bassey, rehearsing with the Paul Busby Big Band The Paul Busby Big Band The Sussex JAZZ MAG Monday 11th - Sunday 24th November 2013 CONTENTS click or touch the blue links to go to that page Features Listings The Column: Eddie Myer Highlights A Brief Guide to Jazz Listings for the Big Bands of Sussex Mon 11th - Sun 24th November An Interview with Paul Busby On The Horizon Venue Guide Reviews Improv Radio Programmes The Jazz Education Section Podcasts You Tube Channels Improv Column: Terry Seabrook Live Reviews A Guide to Learning Jazz in Sussex """"" Credits"" " Contact Us Features Dave Drake, photo courtesy of Mike Guest of Mike courtesy photo Dave Drake, The Column: Eddie Meyer Jazz and Plumbing photo by Mike Guest by Mike photo " The history of jazz is a as a rule questing and enquiring access to the entire history of the part of the histories of both the sorts, are usually aware of the music. Yet the value of recorded creative arts and the equivocal status they occupy in music as a commodity has never entertainment industry. The latter the wider society, and often like to been lower. And while live music has been characterized since the cite plumbers as figures of is more in demand than ever and birth of the mass media in the irreproachable industry and changes to the licensing laws have early 20th century by a continuing usefulness, deserving of respectful removed the iniquitous 2-in-a-bar dialectic between those who employment conditions that they, rule and opened up many new create the music and those who the musicians, feel should be venues for music, rates of pay exploit it commercially, both sides extended to them as well. -

Stand-Up Comedy Mark 3 | University of Kent

09/27/21 Stand-Up Comedy Mark 3 | University of Kent Stand-Up Comedy Mark 3 View Online [1] Abbott, Bud and Costello, Lou 1977. Abbott & Costello: legends of radio. Radio Spirits. [2] Ajaye, Franklyn 2002. Comic insights: the art of stand-up comedy. Silman-James Press. [3] Allen, Tony 2002. Attitude : wanna make something of it?: the secret of stand-up comedy. Gothic Image. [4] Allen, Woody and Tyrell, Steve 1999. Standup comic. Rhino Entertainment Company. [5] Amnesty International 2002. The secret policeman’s ball: a unique collection of live comedy and music for Amnesty International. Amnesty International. [6] Bailey, Bill 2001. Bewilderness. Universal Pictures. [7] 1/25 09/27/21 Stand-Up Comedy Mark 3 | University of Kent Bailey, Bill 2004. Bill Bailey: ‘Part troll’. Universal. [8] Band, Barry 1999. Blackpool’s comedy greats: Bk. 2: The local careers of Dave Morris, Hylda Baker and Jimmy Clitheroe. B.Band. [9] Banks, Morwenna and Swift, Amanda 1987. The joke’s on us: women in comedy from music hall to the present day. Pandora. [10] Barker and C The ‘Image’ in Show Business. Theatre quarterly. 8. [11] Berger, Phil 2000. The last laugh: the world of stand-up comics. Cooper Square Press. [12] Bergson, Henri 1911. Laughter: an essay on the meaning of the comic. Macmillan. [13] Bogad, L. M. 2005. Electoral guerrilla theatre: radical ridicule and social movements. Routledge. [14] Bradbury, David and McGrath, Joe 1998. Now that’s funny!: conversations with comedy writers. Methuen. [15] 2/25 09/27/21 Stand-Up Comedy Mark 3 | University of Kent Brand, Jo Brand new. -

Ropetackle Comedy Festival Chris Difford Andrew Lawrence

SPARKLING ARTS EVENTS IN THE HEART OF SHOREHAM MAY – AUG 2015 CLAIRE MARTIN & LIANE CARROLL SHOWADDYWADDY NINE BELOW ZERO STEVE BELL STEWART LEE RUBY TURNER ROPETACKLE COMEDY FESTIVAL CHRIS DIFFORD ANDREW LAWRENCE ROPETACKLECENTRE.CO.UK MAY 2015 ropetacklecentre.co.uk BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 MAY 2015 WELCOME TO Open Monday – Saturday: 10am – 4.30pm Contact: [email protected] The Ropetackle Café is located in the foyer of Welcome to our summer programme! Full of amazing music, comedy, theatre, Ropetackle Arts Centre. We serve a delicious range of talks, family events, and much more, all running from May – August 2015. Now an teas, coffees, and soft drinks, plus a wonderful menu award-winning venue* we are delighted to offer another exceptional programme of of freshly made sandwiches, paninis, soups, jacket events with something for everybody to enjoy. Our newly re-opened Ropetackle Café potatoes, scrumptious cakes and more. The large, has been a huge success, and we hope you can enjoy its delectable delights, whether light and airy Ropetackle foyer is the perfect place to a coffee during the day, or one of our delicious pre-show meals (see opposite enjoy a relaxing coffee, meet with friends for a light page for more details). As a charitable trust staffed almost entirely by volunteers, lunch, or get some work done with our free wi-fi. donations make a significant contribution to covering our running costs and We have also expanded our pre-show dining programme delivery, and our Friends scheme is a great way to support the Centre experience and are delighted to be working with alongside other benefits (see page 53 for details). -

Donne in Musica N:B Women in Jazz

FONDAZIONE ADKINS CHITI: DONNE IN MUSICA N:B WOMEN IN JAZZ These notes are based on the Foundation’s research materials for books and articles about jazzwomen worldwide. For simplicity we have divided these into six sections. The text is in WORD in order to facilitate transition into documents for www. In a separate file there are 1. General Introduction – Researching Women in Jazz 2. Brief History of Jazz – “blues women” – arrival in Europe 3. The Mediterranean: Women and Jazz in Italy and Turkey 4. Jazzwomen in Serbia, Germany and Great Britain 5. Final Reflections and suggestion for further reading 6. Bibliographies Also enclosed is a link to an American Website for Women in Jazz. Although not omni-comprehensive of the subject, this could be included in own website as further study material. Patricia Adkins Chiti1 1 Musician and musicologist, former Italian State Commissioner for Equal Opportunities, musicology and performing arts, consultant to universities and institutions. During UNESCO World Conference on Cultural Development Policies (Stockholm, 1998), she proposed clauses regarding women and children. In 1978, she created “Donne in Musica” and in 1996 the “Fondazione Adkins Chiti: Donne in Musica”, with a network of nearly 27 thousand women composers, musicians and musicologists in 113 countries and which commissions new works, promotes research and musical projects and maintains huge archives of women’s music. She has written books and over 500 articles on women in music. In 2004 the President of the Italian Republic honoured her with the title of “Cavaliere Ufficiale”. 1 General Introduction – Researching Women in Jazz “Only God can create a tree and only men can play jazz well” (George T. -

NJA British Jazz Timeline with Pics(Rev3) 11.06.19

British Jazz Timeline Pre-1900 – In the beginning The music to become known as ‘jazz’ is generally thought to have been conceived in America during the second half of the nineteenth century by African-Americans who combined their work songs, melodies, spirituals and rhythms with European music and instruments – a process that accelerated after the abolition of slavery in 1865. Black entertainment was already a reality, however, before this evolution had taken place and in 1873 the Fisk Jubilee Singers, an Afro- American a cappella ensemble, came to the UK on a fundraising tour during which they were asked to sing for Queen Victoria. The Fisk Singers were followed into Britain by a wide variety of Afro-American presentations such as minstrel shows and full-scale revues, a pattern that continued into the early twentieth century. [The Fisk Jubilee Singers c1890s © Fisk University] 1900s – The ragtime era Ragtime, a new style of syncopated popular music, was published as sheet music from the late 1890s for dance and theatre orchestras in the USA, and the availability of printed music for the piano (as well as player-piano rolls) encouraged American – and later British – enthusiasts to explore the style for themselves. Early rags like Charles Johnson’s ‘Dill Pickles’ and George Botsford’s ‘Black and White Rag’ were widely performed by parlour-pianists. Ragtime became a principal musical force in American and British popular culture (notably after the publication of Irving Berlin’s popular song ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’ in 1911 and the show Hullo, Ragtime! staged at the London Hippodrome the following year) and it was a central influence on the development of jazz. -

Autograph Auction Saturday 14 December 2013 11:00

Autograph Auction Saturday 14 December 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Radisson Edwardian Heathrow Hotel 140 Bath Road Heathrow UB3 5AW International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Autograph Auction) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Lot: 4 GULLY JOHN: (1783-1863) CARNERA PRIMO: (1906-1967) English Boxer, Sportsman and Italian Boxer, World Heavyweight Politician. Signed Free Front Champion 1933-34. Bold blue envelope panel, addressed in his fountain pen ink signature ('Primo hand to Thomas Clift at the Carnera') on a page removed Magpie & Stumps, Fetter Lane, from an autograph album. One London and dated Pontefract, very slight smudge at the very 27th September 1835 in his conclusion of the signature and hand. Signed ('J Gully') in the some slight show through from lower left corner. Very slightly the signature to the verso. VG irregularly neatly trimmed and Estimate: £60.00 - £80.00 with light age wear, G. The Magpie & Stumps public house is situated opposite the Old Bailey Lot: 5 and was famous for serving BOXING: Small selection of execution breakfasts up until vintage signed postcard 1868 when mass public hangings photographs by the boxers Gene were stopped. Tunney (World Heavyweight Estimate: £80.00 - £100.00 Champion 1926-28), Max Baer (World Heavyweight Champion 1934-35) and Ken Overlin (World Lot: 2 Middleweight Champion 1940-41; WILLARD JESS: (1881-1968) signed to verso). Each of the American World Heavyweight images depict the subjects in full Boxing Champion 1915-19. Blue length boxing poses and all are fountain pen ink signature ('Yours signed in fountain pen inks. truly, Jess Willard') on a slim Some slight corner creasing, G to oblong 8vo piece.