An Appreciation of John Balaban

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Harron Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

RoRbeRr RtR HaRnHçHTH” Rµ eRåR½RbR± eHTRäR½HTH” R ¸RåR½RbR± R² RèHçRtHaR½HT¡ The One with the https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-with-the-routine-50403300/actors Routine With Friends Like https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/with-friends-like-these...-5780664/actors These... If Lucy Fell https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/if-lucy-fell-1514643/actors A Girl Thing https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-girl-thing-2826031/actors The One with the https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-with-the-apothecary-table-7755097/actors Apothecary Table The One with https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-with-ross%27s-teeth-50403297/actors Ross's Teeth South Kensington https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/south-kensington-3965518/actors The One with https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-with-joey%27s-interview-22907466/actors Joey's Interview Sirens https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sirens-1542458/actors The One Where https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-where-phoebe-runs-50403296/actors Phoebe Runs Jane Eyre https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/jane-eyre-1682593/actors The One Where https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-where-ross-got-high-50403298/actors Ross Got High https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/682262/actors Батман и https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%D0%B1%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%BC%D0%B0%D0%BD-%D0%B8- Робин %D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%B8%D0%BD-276523/actors ОглеР´Ð°Ð»Ð¾Ñ‚о е https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%B4%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%BE- -

Fire Guts Old Bori Ami Dations of His Tax Reform Com Springfield, Mass

PAGE EIGHTEEN - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD. Manchester. Conn., Mon., Jan. 8. 1973 • asesseoisosiswsss:^ About Town Staff Increases Congress To Seek Better Obituary Manchester Chapter, Parents Without Partners, will meet Mrs. Patrick Shea Tuesday at 8 p.m. at Communi Planned At Control Of Federal Budget Mrs. Elizabeth Hegarty Shea, ty Baptist Church. All three Town Park Ullman said he hopes the full 78, of 94 Carman Rd., wife of WASHINGTON /A P) - within 60 days, a congressional Department-maintained ice special committee, including Patrick Shea, died Saturday Ladles Gourmet Group of the State ScKobls skating areas in Manchester Congress is preparing to begin budget that would set limits on Manchester Newcomers Club all appropriations. the 16 Senate members, can night at a Manchester convales Public Utilities Commision last will open today for public its organized effort to get better cent home after a long illness. will meet Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. HARTFORD (AP) - Gov. The regular congressional meet by the end of the week and Fridav, has been rejected by skating. controi of the budget—and in Mrs. Shea was bom in Ireland at the home of Mrs. Faith Thomas J. Meskill said today committees then would take begin work on its recommen leaders of the striking Hours for supervised skating the process to regain some of and had lived in the United there will be “ some’’ increase over and produce the money dations. It has all year to Ouellette, 181 Main St. Amalgamated Transit Union. are 3 p.m. to 9 p.m. at Union the power which, its members States for more than 60 years. -

Absoluteabsolute08 Absolute 2008 Absolute Is Published Annually by the Arts and Humanities Division of Oklahoma City Community College

AbsoluteAbsolute08 Absolute 2008 Absolute is published annually by the Arts and Humanities Division of Oklahoma City Community College. All creative pieces are the original works of college students and community members. The views expressed herein are those of the writers and artists. Editorial Board Student Editors Jeffrey Miller Cynthia Praefke Johnathon Seratt Robert Smith Faculty Advisors Jon Inglett Marybeth McCauley Clay Randolph Publications Coordinator April Jackson Graphic Design Michael Cline Cover Art Jennifer Ohsfeldt Cover Design Randy Anderson Doug Blake Cathy Bowman Special Thanks J.B. Randolph, Dr. Cheryl Stanford, Susan VanSchuyver, Ruth Charnay, Dr. Felix Aquino, Dr. Paul Sechrist All information supplied in this publication is accurate at the time of printing; however, changes may occur and will supersede information in this publication. This publication, printed by DPS Printing Services, Inc., is issued by Oklahoma City Community College. A total of 150 copies were printed at a cost of $__________. Oklahoma City Community College complies with all applicable Federal and State laws and regulations and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, age, religion, disability or status as a veteran in any of its policies, practices or procedures. This includes, but is not limited to, admissions, employment, financial aid, and educational services. Oklahoma City Community College is accredited by the Commission on Institutions of Higher Education of the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools and holds a prestigious 10-year accreditation as of 2001. Contents FICTION .............................................................................................................1 Death of a Neighbor . Cynthia Praefke Melinda . Lyndsie Stremlow Fish on the Verge of Change . .Nelson Bundrick Billy Ray . -

The Porcelain Tower, Or, Nine Stories of China

%is<ii^>^ 3 1735 060 217 449 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dar. PR5349 S286 Darlington Atemorial Litrary T-'ki'/d. 5^.^ .:^x^ ,,W^^j^ //^c^%o////iS'^/^/2^ ^.^ . ; LIFE IN CHINA. PORCELAIN TOWER OR, NINE STORIES OP CHINA. COMPILED FROM ORIGINAL SOURCES. By " T. T. T." To raise a tower your arts apply, And build it thrice three stories high; Make every story rich and fair With blocks of wood, in carvinga rare ; With such its ruder form conceal. And make it strong with plates of steel. From the Song of the Pagoda, Jy—SheLorh. EMBELLISHED BY J. LEECH. PHILADELPHIA: LEA AND BLANCHARD. 1842. ^ 5 ^' TO HIS FRIENDS IN GENERAL, AND TO THE PUBLIC IN PARTICULAR, THE ACCOMPANYING SPECIMENS OF REAL CHINA ARE RESPECTFULLY PRESENTED, BY THEIR MOST OBSEQUIOUS SERVANT THE MANUFACTURER, WHO TAKES THIS OPPORTUNITY OF INFORMING ALL PARTIES, (and PARTICULARLY SMALL TEA-PARTIES,) THAT HIS "services" ARE ALWAYS AT THEIR COMMAND. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. Fum-Fum and Fee-Fee before the Em- peror, Frontispiece. Ho-Fi caught in his own trap, - page 8'2 Din-Din suspended in his office, - 57 ^ Hyson flailed by his father, ) - 112 Si-Long's arrival at the Philosopher's, 124 Faw-Faw and Fee-Fee united, ') - 233 - Fum-Fum smoking his own tail, ) 260 " Hey-Ho discovers Fun, " ' ) ^^^ Fun lowered from the window, ) - 2S5 1^ CONTENTS. Page Invocation, , . , . viii Preface, ..... x THE FIRST STORY. Ho-Fi of the Yellow Girdle, . 13 THE SECOND STORY. Kublai Khan ; or The Siege of Kinsai, . 60 THE THIRD STORY. Fashions in Feet; or the Tale of the Beautiful To-To 86 THE FOURTH STORY. -

The Female Gothic Connoisseur: Reading, Subjectivity, and the Feminist Uses of Gothic Fiction

The Female Gothic Connoisseur: Reading, Subjectivity, and the Feminist Uses of Gothic Fiction By Monica Cristina Soare A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Professor Julia Bader Professor Michael Iarocci Spring 2013 1 Abstract The Female Gothic Connoisseur: Reading, Subjectivity, and the Feminist Uses of Gothic Fiction by Monica Cristina Soare Doctor or Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Ian Duncan, Chair In my dissertation I argue for a new history of female Romanticism in which the romance – and particularly the Gothic romance – comes to represent the transformative power of the aesthetic for the female reader. The literary figure in which this formulation inheres is the Female Quixote – an eighteenth-century amalgamation of Cervantes's reading idealist and the satirized figure of the learned woman – who embodies both aesthetic enthusiasm and a feminist claim on the world of knowledge. While the Female Quixote has generally been understood as a satirical figure, I show that she is actually at the forefront of a development in British aesthetics in which art comes to be newly valued as a bulwark against worldliness. Such a development arises as part of mid-eighteenth-century sensibility culture and changes the meaning of an aesthetic practice that had been to that point criticized and satirized – that of over-investment in the arts, associated, as I show, with both the figure of the connoisseur and of the Female Quixote. -

A Paris Journal

BILL NELSON -- PARIS JOURNAL Page 1 of 233 A PARIS JOURNAL By William H. Nelson, Jr. BILL NELSON -- PARIS JOURNAL Page 2 of 233 Editor’s Note: In 1971, President Nixon invaded Laos and ended the embargo against China, the 26th amendment to the Constitution lowered the voting age to 18, and rock star Jim Morrison of The Doors died of cardiac arrest in Paris. The level of US troops in Vietnam stood at 330,000, and American causalities were nearing 45,000. The Stonewall riots in New York City were just two years old, and the nascent lesbian and gay rights movement operated mainly in the shadows – and mainly in New York and California. “AIDS” were assistants to someone in need of help. Bill Nelson’s love for all things French, including its language, lured him to Paris as a young man in 1971, and this daily journal embodies his private thoughts, events and encounters – living on his own, for the first time, in Paris. Bill would in later years return to France many times, often with his students who learned the culture of France through Bill’s tutelage. Friends and students lucky enough to accompany Bill on these trips were impressed by his command of the language, and his seemingly comprehensive knowledge of where to go and what to see made the trips even more memorable. After Bill’s death in 1990, his caretaker and mother started reading Bill’s Paris journal until she came to this sentence on one of the early pages: “I mean there are some things that are going to happen that I shouldn’t like dear Mother to get her hands on, nor Dad either for that matter, so, if either of you are reading now, and if you love me, then gently close the cover and put it away forever.” And so she stopped. -

The Haverfordian, Vols. 54-55, Nov. 1934-June 1936

STACK THE LIBRARY OF HAVERFORD COLLEGE THE GIFT OF M 0.>J^ ^ gl't Accession No. S^ \ b^ (d^ v'ERFORC^ llaberfottrtan i^otjemtjer 1934 — THE HAVERFORDIAN MEHL & LATTA, Inc. WARNER'S Lumber, Coal and for better Building Material Rainey-Wood Ply Wood Soda Service Koppers Coke Wall Board and Celotex ROSEMONT, PA. Opposite R. R. Station Telephone Bryn Mawr 1300, 1301 OTTO FUCHS SALE OR RENTAL Costumes Make-up Wigs Library and Law Books for Plays and Pageants a Specialty OLD BOOKS REBOUND Established 1882 VAN HORN & SON ^416 N. 15TH STREET THEATRICAL COSTUMES Baldwin 4120 12th and Chestnut Sts., Philadelphia The Nearest and the Best E. S. McCAWLEY, Inc. THE Haverford, Pa. COLLEGE BARBER This shop is haunted by the ghosts Of all great Literature, in hosts; SHOP We sell no fakes or trashes FoRTUNATo Russo, Prop. Lovers of books are welcome here, No clerks will babble in your ear. Haircut, 35c Please smoke—but don't drop ashes. Penn St. and Lancaster Ave. "HAUNTED BOOK SHOP"— Bryn Mawr, Pa. Christopher Morley JOHN TRONCELLITI Expert Hair Cutting SPECIAL AHENTION TO HAVERFORD MEN Ardmore Arcade Phone, Ardmore 593 THE HAVERFORDIAN tSTABllSHKO !••• j:: LOTH INC) ^-*3V MADISON AVENUE COR. rONTY-FOURTH STRBCII NEW VORK Wearing Quality The unusual wearing quality of Brooks Brothers' ready-made suits and overcoats comes from three sources. First, the materials are care- O Brnki Brolh*T« fully selected. Second, the cutting and making "Touch?" are done in our own workrooms. And third, we design styles to survive the passing fads of ex- treme clothing, styles and materials to wear with lasting satisfaction, and not just for a season. -

Practical Composition and Rhetoric

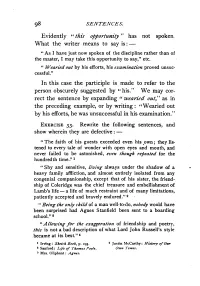

98 SENTENCES. Evidently "this opportunity" has not spoken. What the writer means to say is : — " As I have just now spoken of the discipline rather than of the master, I may take this opportunity to say," etc. " Wearied out by his efforts, his examination proved unsuc cessful." In this case the participle is made to refer to the person obscurely suggested by "his." We may cor rect the sentence by expanding " wearied out," as in the preceding example, or by writing : " Wearied out by his efforts, he was unsuccessful in his examination." Exercise 33. Rewrite the following sentences, and show wherein they are defective : — " The faith of his guests exceeded even his own ; they lis tened to every tale of wonder with open eyes and mouth, and never failed to be astonished, even though repeated for the hundredth time." 1 " Shy and sensitive, living always under the shadow of a heavy family affliction, and almost entirely isolated from any congenial companionship, except that of his sister, the friend ship of Coleridge was the chief treasure and embellishment of Lamb's life — a life of much restraint and of many limitations, patiently accepted and bravely endured."2 " Being the only child of a man well-to-do, nobody would have been surprised had Agnes Stanfield been sent to a boarding school." 8 '-'-Allowing for the exaggeration of friendship and poetry, this is not a bad description of what Lord John Russell's style became at its best." 4 1 Irving : Sketch Book, p. 193. 4 Justin McCarthy: History of Our a Sanford : Life of Thomas Poole. -

Nights at the Hotel Illyria Tanja Jacobs a Thesis

NIGHTS AT THE HOTEL ILLYRIA TANJA JACOBS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN THEATRE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO October 2017 © Tanja Jacobs, 2017 ABSTRACT Nights at the Hotel Illyria describes a production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night which was produced as a part of the 35th Anniversary of Shakespeare in High Park, directed and edited by Tanja Jacobs. The paper places the play in its historical context, and goes on to describe a production concept which sets the action of the play in and around a hotel in the early 1970s, a place for transients and of transience. The paper presents a description of the ways in which this conceptual lens creates a world for the play that not only expresses Shakespeare’s themes — which are also described in detail — but also is directly intelligible to a contemporary audience. Parallels are drawn between the theatrical and socio-cultural innovations of Shakespeare in his writing of Twelfth Night, and tantamount moments of political, social, and artistic upheaval which took place in the Western world during the 1970s. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii List of Images iv Introduction 1 Section 1: The Play The Story 2 The Title 4 Shakespeare’s Sources 5 Events Around the Period of Authorship 7 Production History 8 Genre and Type 9 Who did Shakespeare Write For? 12 Section 2: The Characters 13 Section 3: Shakespeare’s Innovation 22 Section 4: Major Themes Duality -

Language: Its Structure and Use, Fifth Edition Edward Finegan

Language Its Structure and Use Language Its Structure and Use FIFTH EDITION EDWARD FINEGAN University of Southern California Australia Brazil Canada Mexico Singapore Spain United Kingdom United States Language: Its Structure and Use, Fifth Edition Edward Finegan Publisher: Michael Rosenberg Rights Acquisitions Account Manager, Text: Mardell Managing Development Editor: Karen Judd Glinski Schultz Development Editor: Mary Beth Walden Permissions Researcher: Sue Howard Editorial Assistant: Megan Garvey Production Service: Lachina Publishing Services Marketing Manager: Kate Edwards Text Designer: Brian Salisbury Marketing Assistant: Kate Remsberg Sr. Permissions Account Manager, Images: Sheri Marketing Communications Manager: Heather Blaney Baxley Cover Designer: Gopa & Ted2, Inc Content Project Manager: Sarah Sherman Cover Photo: Original artwork by © Werner Senior Art Director: Cate Rickard Barr Hoeflich, Untitled (Hedge series) 2003 Senior Print Buyer: Betsy Donaghey Printer: West Group © 2008, 2004 Thomson Wadsworth, a part of The Thomson Higher Education Thomson Corporation. Thomson, the Star logo, 25 Thomson Place and Wadsworth are trademarks used herein under Boston, MA 02210-1202 license. USA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work cov- ered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced For more information about our products, or used in any form or by any means—graphic, contact us at: electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, Thomson Learning Academic Resource Center recording, taping, web distribution, information 1-800-423-0563 -

UC Berkeley Perspectives in Medical Humanities

UC Berkeley Perspectives in Medical Humanities Title Tell Me Again: Poetry and Prose from The Healing Art of Writing, 2012 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6bx6q0wx ISBN 9780988986534 Author Baranow, Joan Publication Date 2013-12-28 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California tell me again Perspectives in Medical Humanities Perspectives in Medical Humanities publishes scholarship produced or reviewed under the auspices of the University of California Medical Humanities Consortium, a multi-campus collaborative of faculty, students and trainees in the humanities, medicine, and health sciences. Our series invites scholars from the humanities and health care professions to share narratives and analysis on health, healing, and the contexts of our beliefs and practices that impact biomedical inquiry. General Editor Brian Dolan, PhD, Professor of Social Medicine and Medical Humanities, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Recent Titles Clowns and Jokers Can Heal Us: Comedy and Medicine By Albert Howard Carter III (Fall 2011) The Remarkables: Endocrine Abnormalities in Art By Carol Clark and Orlo Clark (Winter 2011) Health Citizenship: Essays in Social Medicine and Biomedical Politics By Dorothy Porter (Winter 2011) What to Read on Love, not Sex: Freud, Fiction, and the Articulation of Truth in Modern Psychological Science By Edison Miyawaki, MD; Foreword by Harold Bloom (Fall 2012) Patient Poets: Illness from Inside Out By Marilyn Chandler McEntyre (Spring 2013) www.UCMedicalHumanitiesPress.com [email protected] This series is made possible by the generous support of the Dean of the School of Medicine at UCSF, the Center for Humanities and Health Sciences at UCSF, and a Multi-Campus Research Program Grant from the University of California Office of the President. -

October 1927

” WALDORF= Collegiate Tuxedos FOR HIRE WALDORF CLOTHING COMPANY “Largest Tuxedo House in Providence” 212 UNION STREET “Jack” Robshaiv, *29, to Serve You The College Drug Store “Over 30 Years Your Druggist” PRESCRIPTIONS SODA, SMOKES, EATS, ICE CREAM ONE BLOCK DOWN FROM THE COLLEGE 895 Smith Street, at River Avenue R. H. Haskins, Phg., Reg. Phar. BILL CASEY Representing The Kennedy Company Dorrance and Westminster Streets Shoiving Duncan Paige, Ltd. Custom Cut College Clothes at the COLLEGE BUILDING EVERY THURSDAY ALEMBIC ADVERTISERS CAN PLEASE YOU— Use the Alembic Directory TELEPHONE GASPEE 0229 A. Slocum & Son THEATRICAL COSTUMERS 37 Weybosset Street, Providence, R. I. TIES B-R-O-A-D-C-A-S-T SHIRTS Reg. U. S. Pat. Off. HOSE Shoes For the College Man $8.50 Headquarters for The Mileage Shoe for Men Mallor}; Hals Who Are Particular Charlie O’Donnell •a •INCM TIONt^' or IHOt HTAILma. HATS AND MEN'S SINCE FURNISHINGS Westminster and 60 Washington Street Dorrance Streets The W. J. Sullivan Company “The House of Rosaries” CLASS PINS CLASS RINGS MEDALS ECCLESIASTICAL WARES IN GOLD. SILVER. BRASS. BRONZE 55 Eddy Street, Providence, R. I. HELP ADVERTISERS MAKE THEIR ADS INVESTMENTS Fletcher Costume Company COSTUMES WIGS MASKS BEARDS All Articles Disinfected After Use DRESS SUITS AND TUXEDOS 524 Westminster Street 421 Weybosset Street GAspee 4685 Opposite Cathedral William J. Feeley McDEVITT’S (Incorporated) PAWTUCKET JEWELER and Distributors of SILVERSMITH Ecclesiastical Wares in Gold, Silver and Bronze Michaels Stern (and) Medals Class Emblems Kuppenheimer The Rosary in Fine Jewels Good Clothes Illustrated List on Application Mallory Forvnes Fine 181 Eddy Street Providence, R.