Debt Management Report 2020-21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Homelessness Monitor: England 2016

The homelessness monitor: England 2016 Suzanne Fitzpatrick, Hal Pawson, Glen Bramley, Steve Wilcox and Beth Watts, Institute for Social Policy, Housing, Environment and Real Estate (I-SPHERE), Heriot-Watt University; Centre for Housing Policy, University of York; City Futures Research Centre, University of New South Wales Executive Summary January 2016 The homelessness monitor 2011-2016 The homelessness monitor is a longitudinal study providing an independent analysis of the homelessness impacts of recent economic and policy developments in England. It considers both the consequences of the post-2007 economic and housing market recession, and the subsequent recovery, and also the impact of policy changes. This fifth annual report updates our account of how homelessness stands in England in 2016, or as close to 2016 as data availability allows. It also highlights emerging trends and forecasts some of the likely future changes, identifying the developments likely to have the most significant impacts on homelessness. While this report focuses on England, parallel homelessness monitors are being published for other parts of the UK. Crisis head office 66 Commercial Street London E1 6LT Tel: 0300 636 1967 Fax: 0300 636 2012 www.crisis.org.uk © Crisis 2015 ISBN 978-1-78519-026-1 Crisis UK (trading as Crisis). Registered Charity Numbers: E&W1082947, SC040094. Company Number: 4024938 Executive summary 3 Executive summary ‘local authority homelessness case actions’ in 2014/15, a rise of 34% since The homelessness monitor series is a 2009/10. While this represents a slight longitudinal study providing an independent (2%) decrease in this indicator of the gross analysis of the homelessness impacts of volume of homelessness demand over the recent economic and policy developments in past year, two-thirds of all local authorities England and elsewhere in the UK.1 This fifth in England reported that overall service annual report updates our account of how demand 'footfall' had actually increased in homelessness stands in England in 2016, or their area in 2014/15. -

Three Essays on the Behavioral, Socioeconomic, and Geographic Determinants of Mortality: Evidence from the United Kingdom and International Comparisons

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 Three Essays on the Behavioral, Socioeconomic, and Geographic Determinants of Mortality: Evidence From the United Kingdom and International Comparisons Laura Kelly University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, and the Epidemiology Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, Laura, "Three Essays on the Behavioral, Socioeconomic, and Geographic Determinants of Mortality: Evidence From the United Kingdom and International Comparisons" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1806. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1806 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1806 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Three Essays on the Behavioral, Socioeconomic, and Geographic Determinants of Mortality: Evidence From the United Kingdom and International Comparisons Abstract This dissertation contains three chapters covering the impact of behavioral, socioeconomic, and geographic determinants of health and mortality in high-income populations, with particular emphasis on the abnormally high mortality in Scotland, and the relative advantages of indirect and direct analyses in estimating national mortality. Chapter one identifies behavioral risk factors underlying mortality variation across small-areas in Great Britain, using the indirect estimation -

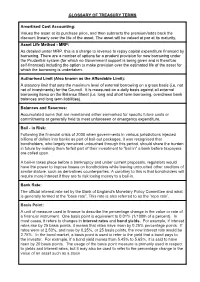

Glossary of Treasury Terms

GLOSSARY OF TREASURY TERMS Amortised Cost Accounting: Values the asset at its purchase price, and then subtracts the premium/adds back the discount linearly over the life of the asset. The asset will be valued at par at its maturity. Asset Life Method - MRP: As detailed under MRP, this is a charge to revenue to repay capital expenditure financed by borrowing. There are a number of options for a prudent provision for new borrowing under the Prudential system (for which no Government support is being given and is therefore self-financed) including the option to make provision over the estimated life of the asset for which the borrowing is undertaken. Authorised Limit (Also known as the Affordable Limit): A statutory limit that sets the maximum level of external borrowing on a gross basis (i.e. not net of investments) for the Council. It is measured on a daily basis against all external borrowing items on the Balance Sheet (i.e. long and short term borrowing, overdrawn bank balances and long term liabilities). Balances and Reserves: Accumulated sums that are maintained either earmarked for specific future costs or commitments or generally held to meet unforeseen or emergency expenditure. Bail - in Risk: Following the financial crisis of 2008 when governments in various jurisdictions injected billions of dollars into banks as part of bail-out packages, it was recognised that bondholders, who largely remained untouched through this period, should share the burden in future by making them forfeit part of their investment to "bail in" a bank before taxpayers are called upon. A bail-in takes place before a bankruptcy and under current proposals, regulators would have the power to impose losses on bondholders while leaving untouched other creditors of similar stature, such as derivatives counterparties. -

Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2017

DIGEST OF UNITED KINGDOM ENERGY STATISTICS 2017 July 2017 This document is available in large print, audio and braille on request. Please email [email protected] with the version you require. Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics Enquiries about statistics in this publication should be made to the contact named at the end of the relevant chapter. Brief extracts from this publication may be reproduced provided that the source is fully acknowledged. General enquiries about the publication, and proposals for reproduction of larger extracts, should be addressed to BEIS, at the address given in paragraph XXVIII of the Introduction. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) reserves the right to revise or discontinue the text or any table contained in this Digest without prior notice This is a National Statistics publication The United Kingdom Statistics Authority has designated these statistics as National Statistics, in accordance with the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 and signifying compliance with the UK Statistics Authority: Code of Practice for Official Statistics. Designation can be broadly interpreted to mean that the statistics: ñ meet identified user needs ONCEñ are well explained and STATISTICSreadily accessible HAVE ñ are produced according to sound methods, and BEENñ are managed impartially DESIGNATEDand objectively in the public interest AS Once statistics have been designated as National Statistics it is a statutory NATIONALrequirement that the Code of Practice S TATISTICSshall continue to be observed IT IS © A Crown copyright 2017 STATUTORY You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. -

Survey Methodology Bulletin 79

{79} Survey Methodology Bulletin May 2019 Contents Preface The methodological challenges of Stephanie 1 protecting outputs from a Flexible Blanchard Dissemination System An investigation into using data Gareth L. 16 science techniques for the Jones processing of the Living Costs and Foods survey Distributive Trade Transformation: Jennifer 28 Methodological Review and Davies Recommendations Forthcoming Courses, 46 Methodology Advisory Service and GSS Methodology Series The Survey Methodology Bulletin is primarily produced to inform staff in the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the wider Government Statistical Service (GSS) about ONS survey methodology work. It is produced by ONS, and ONS staff are encouraged to write short articles about methodological projects or issues of general interest. Articles in the bulletin are not professionally refereed, as this would considerably increase the time and effort to produce the bulletin; they are working papers and should be viewed as such. The bulletin is published twice a year and is available as a download only from the ONS website. The mission of ONS is to improve understanding of life in the United Kingdom and enable informed decisions through trusted, relevant, and independent statistics and analysis. On 1 April 2008, under the legislative requirements of the 2007 Statistics and Registration Service Act, ONS became the executive office of the UK Statistics Authority. The Authority's objective is to promote and safeguard the production and publication of official statistics that serve the public good and, in doing so, will promote and safeguard (1) the quality of official statistics, (2) good practice in relation to official statistics, and (3) the comprehensiveness of official statistics. -

Assessment of Compliance with the Code of Practice for Official Statistics

Assessment of compliance with the Code of Practice for Official Statistics Statistics on the Public Sector Finances (produced by the Office for National Statistics and HM Treasury) Assessment Report 316 October 2015 © Crown Copyright 2015 The text in this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or email: [email protected] About the UK Statistics Authority The UK Statistics Authority is an independent body operating at arm’s length from government as a non-ministerial department, directly accountable to Parliament. It was established on 1 April 2008 by the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007. The Authority’s overall objective is to promote and safeguard the production and publication of official statistics that serve the public good. It is also required to promote and safeguard the quality and comprehensiveness of official statistics, and good practice in relation to official statistics. The Statistics Authority has two main functions: 1. oversight of the Office for National Statistics (ONS) – the executive office of the Authority; 2. independent scrutiny (monitoring -

Euro Medium Term Note Prospectus

20MAY201112144662 London Stock Exchange Group plc (Registered number 5369106, incorporated with limited liability under the laws of England and Wales) £1,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme Under this £1,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the Programme) London Stock Exchange Group plc (the Issuer) may from time to time issue notes (the Notes) denominated in any currency agreed between the Issuer and the relevant Dealer (as defined on page 1). An investment in Notes issued under the Programme involves certain risks. For a description of these risks, see ‘‘Risk Factors’’ below. Application has been made to the Financial Services Authority (the UK Listing Authority) in its capacity as competent authority under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, as amended (the FSMA) for Notes issued during the period of 12 months from the date of this Offering Circular to be admitted to the official list of the UK Listing Authority (the Official List) and to the London Stock Exchange plc (the London Stock Exchange) for such Notes to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s regulated market. References in this Offering Circular to Notes being ‘‘listed’’ (and all related references) shall either mean that such Notes have been admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s regulated market and have been admitted to the Official List or shall be construed in a similar manner in respect of any other EEA State Stock Exchange, as applicable. The expression ‘‘EEA State’’ when used in this Offering Circular has the meaning given to such term in the FSMA (as defined above). -

UK Statistics Authority Business Plan: April 2018 to March 2021

UK Statistics Authority Business Plan April 2018 to March 2021 UK Statistics Authority Business Plan – April 2018 to March 2021 | 1 01 FOREWORD The period of this plan will see the realisation of the There is still work to do on leadership, finance ambition set out in our strategy, Better Statistics, and technology but we are now on a much firmer Better Decisions. footing as we move into the fourth phase of the strategy. Now the focus is on our staff, their skills and The UK has important decisions to make on EU exit how we work together to maximise our collective and our place in the world, the macroeconomy and contribution. We are on track to complete the final industrial strategy, population change and migration, stage of this period of radical change in our three health, security amongst many more. To inform these priority areas: economic statistics, contribution to decisions our job is to provide clear insight quickly, public policy (including through the census and other in fine grained forms and targeted on the issues data collections) and data capability (technology at hand. All our services need to be designed to be and skills) in year five, ready for the next Spending helpful to government, business, communities and Review period. individuals when important choices and judgements are being made. We will face many challenges. To earn trust we need to be professional in all we do. This means we The data revolution has created previously have to demonstrate our impartiality through our unimaginable sources of information for us to work actions. -

UK Statistics Authority Annual Report and Accounts 2012/13

UK Statistics Authority ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2012/13 UK Statistics Authority ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2012/13 Accounts presented to the House of Commons pursuant to section 6(4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Accounts presented to the House of Lords by command of Her Majesty Annual Report presented to Parliament pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the Scottish Parliament pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the National Assembly for Wales pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Annual Report presented to the Northern Ireland Assembly pursuant to section 27(2) of the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 08 July 2013 HC 37 UKSA/2013/01 Note: UK Statistics Authority referred to as ‘the Statistics Board’ in the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 London: The Stationery Office Price £30.00 This is part of a series of departmental publications which, along with the Main Estimates 2013/14 and the document Public Expenditure: Statistical Analyses 2013, present the Government’s outturn for 2012/13 and planned expenditure for 2013/14. © Crown copyright 2013 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/ or e-mail: [email protected]. -

Farming Statistics – Provisional Arable Crop Areas, Yields and Livestock Populations at 1 June 2020 United Kingdom

08 October 2020 Farming Statistics – provisional arable crop areas, yields and livestock populations at 1 June 2020 United Kingdom This release contains first estimates for land use, crop areas and livestock populations on agricultural holdings in the UK and the size of the UK cereals and oilseed rape harvest for 2020. Results are not yet available for poultry, horses, goats, farmed deer, camelids and labour numbers. These will be published with the final results, provisionally scheduled for 17 December 2020. Wales do not produce provisional results and Northern Ireland have been unable to provide provisional data. Therefore, crop areas and livestock numbers for 2019 (with the exception of cattle) have been carried forward for Wales and all data for 2019 has been carried forward for Northern Ireland to allow UK totals to be calculated for 2020. Agricultural land and arable crop areas The total utilised agricultural area (UAA) in the UK has decreased slightly, to just under 17.5 million hectares. The area of total crops and permanent grassland have also seen decreases, whereas uncropped arable land has seen a 57% increase. Crop yields and production Provisional results for 2020 show lower yields for cereal and oilseed crops when compared with the higher yields and above average production seen in 2019. Wheat Wheat production in the UK decreased by 38%, from 16.2 million tonnes in 2019 to 10.1 million tonnes in 2020. The UK yield of 7.2 tonnes per hectare is lower than the five year average of 8.4 tonnes per hectare. Barley Total barley production increased by 3.9%, from 8.0 million tonnes in 2019 to 8.4 million tonnes in 2020. -

Statistics Making an Impact

John Pullinger J. R. Statist. Soc. A (2013) 176, Part 4, pp. 819–839 Statistics making an impact John Pullinger House of Commons Library, London, UK [The address of the President, delivered to The Royal Statistical Society on Wednesday, June 26th, 2013] Summary. Statistics provides a special kind of understanding that enables well-informed deci- sions. As citizens and consumers we are faced with an array of choices. Statistics can help us to choose well. Our statistical brains need to be nurtured: we can all learn and practise some simple rules of statistical thinking. To understand how statistics can play a bigger part in our lives today we can draw inspiration from the founders of the Royal Statistical Society. Although in today’s world the information landscape is confused, there is an opportunity for statistics that is there to be seized.This calls for us to celebrate the discipline of statistics, to show confidence in our profession, to use statistics in the public interest and to champion statistical education. The Royal Statistical Society has a vital role to play. Keywords: Chartered Statistician; Citizenship; Economic growth; Evidence; ‘getstats’; Justice; Open data; Public good; The state; Wise choices 1. Introduction Dictionaries trace the source of the word statistics from the Latin ‘status’, the state, to the Italian ‘statista’, one skilled in statecraft, and on to the German ‘Statistik’, the science dealing with data about the condition of a state or community. The Oxford English Dictionary brings ‘statistics’ into English in 1787. Florence Nightingale held that ‘the thoughts and purpose of the Deity are only to be discovered by the statistical study of natural phenomena:::the application of the results of such study [is] the religious duty of man’ (Pearson, 1924). -

6.4770 Civil Service Quarterly Issue 18

AUSTRALIA’S TOP CIVIL SERVANT, MARTIN PARKINSON: IS THE UK CIVIL SERVICE FIT FOR PURPOSE IN A POST-BREXIT BRITAIN? LESSONS FROM THE ORIENT TAKING CARE OF CHILDREN THE RISE OF SELF-DRIVING VEHICLES Issue 18 – October 2018 Subscribe for free here: quarterly.blog.gov.uk #CSQuarterly 2 CIVIL SERVICE QUARTERLY | Issue 18 – October 2018 CONTENTS LANDING THE CASE FOR HEATHROW Caroline Low, Director of Heathrow Expansion, 4 EXPANSION Department for Transport MAKING 30 HOURS CHILDCARE COUNT Michelle Dyson, Director, Early Years and Childcare, 8 Department for Education WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT FRAUD Mark Cheeseman, Deputy Director, Public Sector Fraud, 12 Cabinet Office MODERNISING THE GOVERNMENT ESTATE: James Turner, Deputy Director Strategy & Engagement, 16 A TRANSFORMATION STRATEGY Office of Government Property, Cabinet Office THE FUTURE OF TRANSPORT: Iain Forbes, Head of the Centre for Connected and 20 PUTTING THE UK IN THE DRIVING SEAT Autonomous Vehicles, Department for Transport and Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy DELIVERING JUSTICE IN A DIGITAL WORLD Susan Acland-Hood, CEO, HM Courts & Tribunals Service, 24 Ministry of Justice SPOTLIGHT: DEVELOPING THE Fiona Linnard, Government Digital Service 28 LEADERS OF TOMORROW Rob Kent-Smith, UK Statistics Authority DODGING THE ICEBERGS - HOW TO Charlene Chang, Senior Director, Transformation, 30 MAKE GOVERNMENT MORE AGILE Public Service Division, Singapore Jalees Mohammed, Senior Assistant Director, Transformation, Public Service Division, Singapore IN CONVERSATION: DR MARTIN PARKINSON, Martin Parkinson, Australia’s Secretary of the Department of the 36 AUSTRALIA’S SECRETARY OF THE Prime Minister and Cabinet DEPARTMENT OF THE PRIME MINISTER AND CABINET Civil Service Quarterly opens CONTACT US EDITORIAL BOARD up the Civil Service to greater [email protected] Sir Chris Wormald, Permanent Secretary, collaboration and challenge, Room 317, 70 Whitehall, Department of Health (chair) showcases excellence and invites London, SW1A 2AS discussion.