Sudan Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sudan: Freedom in the World 2020

4/8/2020 Sudan | Freedom House FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 Sudan 12 NOT FREE /100 Political Rights 2 /40 Civil Liberties 10 /60 LAST YEAR'S SCORE & STATUS 7 /100 Not Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. https://freedomhouse.org/country/sudan/freedom-world/2020 1/24 4/8/2020 Sudan | Freedom House Overview The military leaders and civilian protesters who ousted the repressive regime of Omar al-Bashir and his National Congress Party (NCP) in 2019 are uneasy partners in a transitional government that—if successful—will be replaced by an elected government in 2022. Civic space is slowly opening to individuals and opposition parties, but security personnel associated with the abuses of old regime remain influential, and their commitment to political freedoms and civil liberties is unclear. Key Developments in 2019 President Omar al-Bashir, who came to power in a coup d’état in 1989, was overthrown by the military in April, after a protest movement beginning in December 2018 placed growing pressure on the government. The military initially attempted to rule without the input of civilian protesters, who originally demonstrated against rising commodity prices and pervasive economic hardship before calling for al-Bashir’s resignation as the year opened. Security forces killed 127 protesters in the capital of Khartoum in June, sparking a backlash that forced the short-lived junta to include civilian leaders in a new transitional government as part of a power-sharing agreement reached in August. Al-Bashir was arrested by the military junta and charged with corruption by the succeeding transitional government in August. -

Dongola 2015–2016

Book chapter title: Women in the Southwest Annex Authors: Adam Łajtar https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3842-2180 Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1637-4261 Book: Dongola 2015–2016. Fieldwork, conservation and site management Editors: W. Godlewski, D. Dzierzbicka, & A. Łajtar Series: PCMA Excavation Series 5 Year: 2018 Pages: 75–78 https://doi.org/10.31338/uw.9788323534877.pp.75-78 Publisher: Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw (PCMA UW); University of Warsaw Press www.pcma.uw.edu.pl – [email protected] – [email protected] www.wuw.pl How to cite this chapter: Łajtar, A., and van Gerven Oei, V.W.J. (2018). Women in the Southwest Annex. In W. Godlewski, D. Dzierzbicka, & A. Łajtar (Eds.), Dongola 2015–2016. Fieldwork, conservation and site management (pp. 75–78). PCMA Excavation Series 5. Warsaw: University of Warsaw Press. https://doi.org/10.31338/uw.9788323534877.pp.75-78 DONGOLA 2015–2016 FIELDWORK, CONSERVATION AND SITE MANAGEMENT EDITORS Włodzimierz GodleWski dorota dzierzbicka adam łajtar POLISH CENTRE OF MEDITERRANEAN ARCHAEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW POLISH CENTRE OF MEDITERRANEAN ARCHAEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW PCMA Excavation Series 5 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Piotr Bieliński Krzysztof M. Ciałowicz Wiktor Andrzej Daszewski Michał Gawlikowski Włodzimierz Godlewski Tomasz Waliszewski EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Jean Charles Balty Charles Bonnet Giorgio Bucellatti Stan Hendrickx Johanna Holaubek PARTNERS IN THE PROJECT POLISH CENTRE OF MEDITERRANEAN ARCHAEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW QATAR-SUDAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL -

QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY of the STATE of QATAR ______TABLE of CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1

CASE CONCERNING MARITIME DELIMITATION AND TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS BETWEEN QATAR AND BAHRAIN (QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY OF THE STATE OF QATAR _____________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1. Qatar's Case and Structure of Qatar's Reply Section 2. Deficiencies in Bahrain's Written Pleadings Section 3. Bahrain's Continuing Violations of the Status Quo PART II - THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND CHAPTER II - THE TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY OF QATAR Section 1. The Overall Geographical Context Section 2. The Emergence of the Al-Thani as a Political Force in Qatar Section 3. Relations between the Al-Thani and Nasir bin Mubarak Section 4. The 1913 and 1914 Conventions Section 5. The 1916 Treaty Section 6. Al-Thani Authority throughout the Peninsula of Qatar was consolidated long before the 1930s Section 7. The Map Evidence CHAPTER III - THE EXTENT OF THE TERRITORY OF BAHRAIN Section 1. Bahrain from 1783 to 1868 Section 2. Bahrain after 1868 PART III - THE HAWAR ISLANDS AND OTHER TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS CHAPTER IV - THE HAWAR ISLANDS Section 1. Introduction: The Territorial Integrity of Qatar and Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 2. Proximity and Qatar's Title to the Hawar Islands Section 3. The Extensive Map Evidence supporting Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 4. The Lack of Evidence for Bahrain's Claim to have exercised Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands from the 18th Century to the Present Day Section 5. The Bahrain and Qatar Oil Concession Negotiations between 1925 and 1939 and the Events Leading to the Reversal of British Recognition of Hawar as part of Qatar Section 6. -

2 September 2006 Page 1

Satzinger 11th Conference of Nubian Studies; Warsaw, 27 August - 2 September 2006 Page 1 The Nubian Language / Dialect Group Desasters: • Mahdist wars, 1880s • The First Civil War 1965-72, • The Second Civil War, 1983 to present, Darfûr Conflict, from 2001/2002/2003 onwards. • 1983/1984 a horrid famine, with nearly 100,000 Darfûris left dead • Aswân Dam, after 1900 • High Dam, after 1960 It is hard to tell what is the present situation of all those tiny groups of speakers of various languages in the area: extinction, deplacement, decimation, enslavement. The pre-war situation was like this: Hill Nubian G h u l f â n : 16,000 speakers (1984 R. C. Stevenson). Northern Sudan, K o r d o f a n , in two hill ranges 25 to 30 miles south of Dilling: Ghulfan Kurgul and Ghulfan Morung. K a d a r u : 12,360 speakers (2000 “WCD”). Northern Sudan, K o r d o f a n Province, Nuba mountains, Kadaru Hills between Dilling and Delami. D i l l i n g : 5,295 speakers (1984 R. C. Stevenson). Northern Sudan, Southern K o r d o f a n , town of Dilling and surrounding hills, including Kudr. D â i r : 1,000 speakers (1978 “GR”). Northern Sudan, west and south parts of Jebel Dair, K o r d o f a n . E l - H u g e i r â t : 200 speakers (2000 Brenzinger). Northern Sudan, West K o r d o f a n on El Hugeirat Hills. K a r k o : 12,986 speakers (1984 R. -

1 Name 2 History

Sudan This article is about the country. For the geographical two civil wars and the War in the Darfur region. Sudan region, see Sudan (region). suffers from poor human rights most particularly deal- “North Sudan” redirects here. For the Kingdom of North ing with the issues of ethnic cleansing and slavery in the Sudan, see Bir Tawil. nation.[18] For other uses, see Sudan (disambiguation). i as-Sūdān /suːˈdæn/ or 1 Name السودان :Sudan (Arabic /suːˈdɑːn/;[11]), officially the Republic of the Sudan[12] Jumhūrīyat as-Sūdān), is an Arab The country’s place name Sudan is a name given to a جمهورية السودان :Arabic) republic in the Nile Valley of North Africa, bordered by geographic region to the south of the Sahara, stretching Egypt to the north, the Red Sea, Eritrea and Ethiopia to from Western to eastern Central Africa. The name de- the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African or “the ,(بلاد السودان) rives from the Arabic bilād as-sūdān Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west and Libya lands of the Blacks", an expression denoting West Africa to the northwest. It is the third largest country in Africa. and northern-Central Africa.[19] The Nile River divides the country into eastern and west- ern halves.[13] Its predominant religion is Islam.[14] Sudan was home to numerous ancient civilizations, such 2 History as the Kingdom of Kush, Kerma, Nobatia, Alodia, Makuria, Meroë and others, most of which flourished Main article: History of Sudan along the Nile River. During the predynastic period Nu- bia and Nagadan Upper Egypt were identical, simulta- neously evolved systems of pharaonic kingship by 3300 [15] BC. -

Excessive and Deadly the Use of Force, Arbitrary Detention and Torture Against

EXCESSIVE AND DEADLY THE USE OF FORCE, ARBITRARY DETENTION AND TORTURE AGAINST PROTESTERS IN SUDAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. ACJPS works to monitor and promote respect for human rights and legal reform in Sudan. ACJPS has a vision of a Sudan where all people can live and prosper free from fear and in a state committed to justice, equality and peace. ACJPS has offices in the US, UK, and Uganda. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom ©Amnesty International 2014 Index: AFR 54/020/2014 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission -

The Case of Dongolawi Nubian

Taha A. Taha Florida A & M University The lexicon in endangered languages: The case of Dongolawi Nubian Abstract. Lexical change and attrition is one of the main signs or symptoms of language endangerment that can eventually lead to structural changes. And although the phenomenon of language endangerment/death has received much attention in sociolinguistic studies, the changes in vocabulary associated with it has not been given the same attention. This paper examines the sociolinguistic situation of Dongolawi Nubian*, a language variety that belongs to the Eastern- Sudanic group of the Nilo-Saharan family which is spoken in the northern region of Sudan. More specifically, the paper analyses a sample of DN lexicon with the purpose of identifying the extent of semantic change, including lexical change, attrition, borrowing, and other additions. Analysis of data reflects extensive borrowing from Sudanese Arabic (SA), loss of items associated with traditional ways of life, some of which are replaced while others are not. The study indicates that, despite heavy borrowing, the basic structure of the language variety still remains intact, with no apparent major changes in syntax such as word order. Hence, it is argued that the DN situation is not hopelessly irreversible, and that the variety could still be revitalized as long as there is willingness, commitment, and collaboration of efforts and resources on the part of policy makers, speakers of the language variety, and other organizations concerned with language endangerment. Keywords: Dongolawi Nubian, endangerment, Sudan Arabic, attrition, borrowing. * The following abbreviations are used in reference to different language varieties: Ar. =Arabic; DN = Dongolawi Nubian; Eng = English; Egy. -

Map of South Sudan

UNITED NATIONS SOUTH SUDAN Geospatial 25°E 30°E 35°E Nyala Ed Renk Damazin Al-Fula Ed Da'ein Kadugli SUDAN Umm Barbit Kaka Paloich Ba 10°N h Junguls r Kodok Āsosa 10°N a Radom l-A Riangnom UPPER NILEBoing rab Abyei Fagwir Malakal Mayom Bentiu Abwong ^! War-Awar Daga Post Malek Kan S Wang ob Wun Rog Fangak at o Gossinga NORTHERN Aweil Kai Kigille Gogrial Nasser Raga BAHR-EL-GHAZAL WARRAP Gumbiel f a r a Waat Leer Z Kuacjok Akop Fathai z e Gambēla Adok r Madeir h UNITY a B Duk Fadiat Deim Zubeir Bisellia Bir Di Akobo WESTERN Wau ETHIOPIA Tonj Atum W JONGLEI BAHR-EL-GHAZAL Wakela h i te LAKES N Kongor CENTRAL Rafili ile Peper Bo River Post Jonglei Pibor Akelo Rumbek mo Akot Yirol Ukwaa O AFRICAN P i Lol b o Bor r Towot REPUBLIC Khogali Pap Boli Malek Mvolo Lowelli Jerbar ^! National capital Obo Tambura Amadi WESTERN Terakeka Administrative capital Li Yubu Lanya EASTERN Town, village EQUATORIAMadreggi o Airport Ezo EQUATORIA 5°N Maridi International boundary ^! Juba Lafon Kapoeta 5°N Undetermined boundary Yambio CENTRAL State (wilayah) boundary EQUATORIA Torit Abyei region Nagishot DEMOCRATIC Roue L. Turkana Main road (L. Rudolf) Railway REPUBLIC OF THE Kajo Yei Opari Lofusa 0 100 200km Keji KENYA o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 50 100mi CONGO o e The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Proceedings of the 15Th SIGMORPHON Workshop on Computational Research in Phonetics, Phonology, and Morphology, Pages 1–10 Brussels, Belgium, October 31, 2018

SIGMORPHON 2018 The 15th SIGMORPHON Workshop on Computational Research in Phonetics, Phonology, and Morphology Proceedings of the Workshop October 31, 2018 Brussels, Belgium c 2018 The Association for Computational Linguistics Order copies of this and other ACL proceedings from: Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) 209 N. Eighth Street Stroudsburg, PA 18360 USA Tel: +1-570-476-8006 Fax: +1-570-476-0860 [email protected] ISBN 978-1-948087-76-6 ii Preface Welcome to the 15th SIGMORPHON Workshop on Computational Research in Phonetics, Phonology, and Morphology, to be held on October 31, 2018 in Brussels, Belgium. The workshop aims to bring together researchers interested in applying computational techniques to problems in morphology, phonology, and phonetics. Our program this year highlights the ongoing and important interaction between work in computational linguistics and work in theoretical linguistics. This year, however, a new focus on low resource approaches to morphology is emerging as a consequence of the SIGMORPHON 2016 and CoNLL shared tasks on morphological reinflection across a wide range of languages. We received 36 submissions, and after a competitive reviewing process, we accepted 19. Due to time limitations, 6 papers were chosen for oral presentations, the remaining papers are presented as posters. The workshop also includes a joint poster session with CoNLL, on the CoNLL–SIGMORPHON 2018 Shared Task: Universal Morphological Reinflection. We are grateful to the program committee for their careful and thoughtful reviews -

Sudan, Performed by the Much Loved Singer Mohamed Wardi

Confluence: 1. the junction of two rivers, especially rivers of approximately equal width; 2. an act or process of merging. Oxford English Dictionary For you oh noble grief For you oh sweet dream For you oh homeland For you oh Nile For you oh night Oh good and beautiful one Oh my charming country (…) Oh Nubian face, Oh Arabic word, Oh Black African tattoo Oh My Charming Country (Ya Baladi Ya Habbob), a poem by Sidahmed Alhardallou written in 1972, which has become one of the most popular songs of Sudan, performed by the much loved singer Mohamed Wardi. It speaks of Sudan as one land, praising the country’s diversity. EQUAL RIGHTS TRUST IN PARTNERSHIP WITH SUDANESE ORGANISATION FOR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT In Search of Confluence Addressing Discrimination and Inequality in Sudan The Equal Rights Trust Country Report Series: 4 London, October 2014 The Equal Rights Trust is an independent international organisation whose pur- pose is to combat discrimination and promote equality as a fundamental human right and a basic principle of social justice. © October 2014 Equal Rights Trust © Photos: Anwar Awad Ali Elsamani © Cover October 2014 Dafina Gueorguieva Layout: Istvan Fenyvesi PrintedDesign: in Dafinathe UK Gueorguieva by Stroma Ltd ISBN: 978-0-9573458-0-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by other means without the prior written permission of the publisher, or a licence for restricted copying from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd., UK, or the Copyright Clearance Centre, USA. -

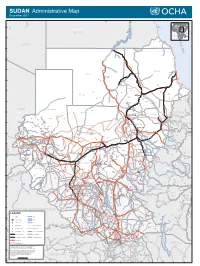

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus -

Sudan, Country Information

Sudan, Country Information SUDAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III HISTORY IV STATE STRUCTURES V HUMAN RIGHTS HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS ANNEX A - CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B - LIST OF MAIN POLITICAL PARTIES ANNEX C - GLOSSARY ANNEX D - THE POPULAR DEFENCE FORCES ACT 1989 ANNEX E - THE NATIONAL SERVICE ACT 1992 ANNEX F - LIST OF THE MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF SUDAN ANNEX G - REFERENCES TO SOURCE DOCUMENTS 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum/human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum/human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for accuracy, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up-to-date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom.