Interview with Professor Frederick Witzig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aquatic Synthesis for Voyageurs National Park

Aquatic Synthesis for Voyageurs National Park Information and Technology Report USGS/BRD/ITR—2003-0001 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Technical Report Series The Biological Resources Division publishes scientific and technical articles and reports resulting from the research performed by our scientists and partners. These articles appear in professional journals around the world. Reports are published in two report series: Biological Science Reports and Information and Technology Reports. Series Descriptions Biological Science Reports ISSN 1081-292X Information and Technology Reports ISSN 1081-2911 This series records the significant findings resulting These reports are intended for publication of book- from sponsored and co-sponsored research programs. length monographs; synthesis documents; compilations They may include extensive data or theoretical analyses. of conference and workshop papers; important planning Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and and reference materials such as strategic plans, standard high-quality standards as their journal counterparts. operating procedures, protocols, handbooks, and manuals; and data compilations such as tables and bibliographies. Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and high-quality standards as their journal counterparts. Copies of this publication are available from the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, Virginia 22161 (1-800-553-6847 or 703-487-4650). Copies also are available to registered users from the Defense Technical Information Center, Attn.: Help Desk, 8725 Kingman Road, Suite 0944, Fort Belvoir, Virginia 22060-6218 (1-800-225-3842 or 703-767-9050). An electronic version of this report is available on-line at: <http://www.cerc.usgs.gov/pubs/center/pdfdocs/ITR2003-0001.pdf> Front cover: Aerial photo looking east over Namakan Lake, Voyageurs National Park. -

Voyageurs National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Voyageurs National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2007/007 THIS PAGE: A geologist highlights a geologic contact during a Geologic Resource Evaluation scoping field trip at Voyageurs NP, MN ON THE COVER: Aerial view of Voyageurs NP, MN NPS Photos Voyageurs National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2007/007 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 June 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer- reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly- published newsletters. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

Minnesota in Profile

Minnesota in Profile Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Landscape (Maps) ........................................................................................14 -

Voyageurs National Park Visitor Study

Voyageurs National Park Visitor Study The Visitor Services Project 2 OMB Approval 1024-0000 Expiration Date: 8-31-98 3 DIRECTIONS One adult in your group should complete the questionnaire. It should only take a few minutes. When you have completed the questionnaire, please seal it with the sticker provided and drop it in any U.S. mailbox. We appreciate your help. PRIVACY ACT and PAPERWORK REDUCTION ACT statement: 16 U.S.C. 1a-7 authorizes collection of this information. This information will be used by park managers to better serve the public. Response to this request is voluntary. No action may be taken against you for refusing to supply the information requested. Your name is requested for follow-up mailing purposes only. When analysis of the questionnaire is completed, all name and address files will be destroyed. Thus the permanent data will be anonymous. Please do not put your name or that of any member of your group on the questionnaire. Data collected through visitor surveys may be disclosed to the Department of Justice when relevant to litigation or anticipated litigation, or to appropriate Federal, State, local or foreign agencies responsible for investigating or prosecuting a violation of law. An agency may not conduct or sponsor, and a person is not required to respond to, a collection of information unless it displays a currently valid OMB control number. Burden estimate statement: Public reporting burden for this form is estimated to average 12 minutes per response. Direct comments regarding the burden estimate or any other aspect of this form to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs of OMB, Attention Desk Officer for the Interior Department, Office of Management and Budget, Washington, D.C. -

Minnesota Statewide Multiple Property Documentation Form for the Woodland Tradition

Minnesota Statewide Multiple Property Documentation Form for the Woodland Tradition Submitted to the Minnesota Department of Transportation Submitted by Constance Arzigian Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse July 2008 MINNESOTA STATEWIDE MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM FOR THE WOODLAND TRADITION FINAL Mn/DOT Agreement No. 89964 MVAC Report No. 735 Authorized and Sponsored by: Minnesota Department of Transportation Submitted by Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse 1725 State Street La Crosse WI 54601 Principal Investigator and Report Author Constance Arzigian July 2008 NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) (Expires 1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. __X_ New Submission ____ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Woodland Tradition in Minnesota B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) The Brainerd Complex: Early Woodland in Central and Northern Minnesota, 1000 B.C.–A.D. 400 The Southeast Minnesota Early Woodland Complex, 500–200 B.C. The Havana-Related Complex: Middle Woodland in Central and Eastern Minnesota, 200 B.C.–A.D. -

Crossing Boundaries for the Border Lakes Region

Wilderness News FROM THE QUETICO SUPERIOR FOUNDATION FALL 2008 quetico superior country The Quetico Superior Foundation, established in 1946, encourages and supports the protection of the ecological, cultural and historical resources of the Quetico Superior region. Near Tettegouche State Park. Photo by Jim Gindorff. Crossing Boundaries for the “The loss of silence in our lives is a great tragedy of our civilization. Canoeing is one of the finest ministries that can Border Lakes Region happen.” By Charlie Mahler, Wilderness News Contributor – Reverend Paul Monson, Board Member In an era of increasing partnership “It’s not that there aren’t other collaboratives that of the Listening Point Foundation and a in the Quetico Superior region, the are interested in similar types of objectives,” he strong believer in the restorative value of said. “I think one of the things that makes this col- camping and canoeing. Border Lakes Partnership provides laborative unique is that the interested parties got July, 24 1937 - October 28, 2008 a model for what cooperative together because of a sense of common purpose. In efforts can accomplish. other cases, some of these more collaborative groups that have worked across agencies have got- The collaborative has been at work since 2003 ten together because there’s been conflict or issues developing cross-boundary strategies for managing they needed to resolve.” forest resources, reducing hazardous forest fuels, and conserving biodiversity in the region. Members Shinneman, himself, embodies the shared nature like the U.S. Forest Service Northern Research of the Border Lakes Partnership’s efforts. “My posi- Station, Superior National Forest, Minnesota tion is really a unique one,” he said. -

Quest for Excellence: a History Of

QUEST FOR EXCELLENCE a history of the MINNESOTA COUNCIL OF PARKS 1954 to 1974 By U. W Hella Former Director of State Parks State of Minnesota Edited By Robert A. Watson Associate Member, MCP Published By The Minnesota Parks Foundation Copyright 1985 Cover Photo: Wolf Creek Falls, Banning State Park, Sandstone Courtesy Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Dedicated to the Memory of JUDGE CLARENCE R. MAGNEY (1883 - 1962) A distinguished jurist and devoted conser vationist whose quest for excellence in the matter of public parks led to the founding of the Minnesota Council of State Parks, - which helped insure high standards for park development in this state. TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward ............................................... 1 I. Judge Magney - "Giant of the North" ......................... 2 II. Minnesota's State Park System .............................. 4 Map of System Units ..................................... 6 Ill. The Council is Born ...................................... 7 IV. The Minnesota Parks Foundation ........................... 9 Foundation Gifts ....................................... 10 V. The Council's Role in Park System Growth ................... 13 Chronology of the Park System, 1889-1973 ................... 14 VI. The Campaign for a National Park ......................... 18 Map of Voyageurs National Park ........................... 21 VII. Recreational Trails and Boating Rivers ....................... 23 Map of Trails and Canoe Routes ........................... 25 Trail Legislation, 1971 ................................... -

Koochiching State Forest

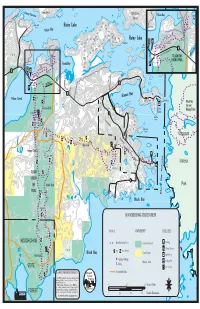

Grassy Narrows Grassy Island Grindstone Tilson Bay 0.2 mi. Frank Island Bay Bald Rock Rainy Lake W Point Tilson Bay W 0.3 mi. Rainy Lake 0.3 mi. Neil Point 0.3 mi. Little American 0.2 mi. W 11 Island U. S. F. S. W 6.5 mi. to International Falls TILSON BAY Frank Bay X HIKING TRAIL Frank Bay X W X 11 W W X DETAIL 11 11 1.3 k. Krause Bay Tilson Creek 0.7 k. X X Island View Dove Point Black Bay Ski and Green Trail 461 Dove Hiking Trails X Island 0.3 k. 96 W Sha Sha X Voyageurs Point 0.3 k. 0.1 k. X X 0.9 k. Steeprock Island Voyageurs X 0.1 k. Tilson National Creek X X X 2.3 k. Blue Trail East Voyageurs Orange Trail X Trail 1.6 k. 0.5 k. 0.3 k. 1.2 k. Tilson Trail X National Park 1.0 k. Perry Point X U. S. F. S. TILSON 0.6 k. CREEK 0.4 k. 96 SKI Yellow Trail Park TRAIL 0.6 k. X 1150 Black Bay Narrows 0.9 k. Black Bay 0.4 k. 1130 KOOCHICHING STATE FOREST X 1140 1.3 k. TRAILS OWNERSHIP FACILITIES 1.1 k. KOOCHICHING Non Motorized Trails State Forest Land Parking 1120 Visitor Center U. S. F. S. easy more difficult Black Bay County Land Red Trail Boat Ramp 1110 W = Hiking/Walking National Land Fishing Pier X = Skiing STATE Trail Shelter X LOOKING FOR MORE INFORMATION ? Snowmobile Trails 0.8 k. -

Plenary Speaker Biographical Sketches and Oral and Poster

MN TWS 2016 Annual Meeting Plenary Speaker Biographical Sketches And Oral and Poster Abstracts Draft 4 February 2016 1 MN TWS 2016 Annual Meeting Fire Ecology Plenary Session Focus on Fire - A Critical Ecological Process for the Maintenance of Ecosystems, Communities, and Habitats Plenary Speaker Biographical Sketches Dwayne Elmore Wildlife Extension Specialist and Bollenbach Chair in Wildlife Biology, Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management, Oklahoma State University 008 C Ag Hall, Stillwater, OK 74078-6013; 405-744-9636; [email protected] Specific areas of Dwayne Elmore’s interests include wildlife habitat relationships, the role of disturbance in maintaining sustainable ecosystems, and social constraints to conservation. Dwayne works with a team of faculty, students, agencies, and landowners studying grassland birds in tallgrass prairie and their response to the interacting processes of fire and large herbivore grazing. Major findings indicate that both breeding and wintering bird communities are strongly influenced by the fire-grazing interaction with various species selecting for distinct landscape patches characterized by differing times since fire. Migratory species that are present during the breeding season or during the winter, such as Henslow’s sparrow, LeConte’s sparrow, Sprague’s pipit, and upland sandpiper strongly select for areas with distinct vegetation structure reflecting their habitat needs during the period of year they use the habitat. The non-migratory greater prairie-chicken, however, requires a mosaic of habitat patches across a broad landscape that provides the full spectrum of a broad set of habitat conditions required during distinct portions of its yearly cycle. Furthermore, most breeding birds reach their maximum abundance in landscapes with higher levels of landscape patchiness resulting from complex disturbance patterns. -

The Logging Era at LY Oyageurs National Park Historic Contexts and Property Types

The Logging Era at LY oyageurs National Park Historic Contexts and Property Types Barbara Wyatt, ASLA Institute for Environmental Studies Department of Landscape Architecture University of Wisconsin-Madison Midwest Support Office National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska This report was prepared as part of a Cooperative Park Service Unit (CPSU) between the Midwest Support Office of the National Park Service and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The grant was supervised by Professor Arnold R. Alanen of the Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and administered by the Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin Madison. Cover Photo: Logging railroad through a northern Minnesota pine forest. The Virginia & Rainy Lake Company, Virginia, Minnesota, c. 1928 (Minnesota Historical Society). - -~------- ------ - --- ---------------------- -- The Logging Era at Voyageurs National Park Historic Contexts and Property Types Barbara Wyatt, ASLA Institute for Environmental Studies Department of Landscape Architecture University of Wisconsin-Madison Midwest Support Office National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 1999 This report was prepared as part of a Cooperative Park Service Unit (CPSU) between the Midwest Support Office of the National Park Service and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The grant was supervised by Professor Arnold R. Alanen of the Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and administered by the Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison. -

Newsletter Spring/Summer 2019

Newsletter Spring/Summer 2019 Help Keep Voyageurs Wild Forever voyageurs.org Some time has passed since saws laid low the old growth old structures. But more importantly, park establishment forests and engines roared through the wilderness that is now meant the permanent preservation of the woods, water, and Voyageurs National Park. wilderness for future generations unimpaired, no more could this land be exploited and degraded. Though this period of resource exploitation seems a distant memory, the fingerprints of human use are not so easily But are we really leaving Voyageurs unimpaired for future erased. The decisions made almost a century ago have generations? outlived those who made them, the scars still visibly etched over the expansive wilderness. Straight line clearings in Aldo Leopold realized the inherent contradiction in the bogs and wetlands from old roads still persist throughout the preservation of wild places, stating that “all conservation of Kabetogama Peninsula, and the scalloped tire ruts from trucks wildness is self-defeating, for to cherish we must see and and other equipment are still imprinted on the forest floor. fondle, and when enough have seen and fondled, there is no In and around Hoist and Moose Bay, the old railroad grade wilderness left to cherish.” endures, weaving around the ridges and through the lowlands. The continual use of Voyageurs by all of us has contributed The 5-foot high berms on either side still stand tall in places. to impacts on this incredible area that are easily avoidable Beavers have helped dismantle this grade by damming the with a concerted effort.